Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

Mandeep Dagli

W. Dee Dockery

Gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage is a common, potentially life-threatening cause of acute hospital admission and often requires intensive care unit (ICU)-level care. Before radiologic evaluation, the clinical evaluation should focus on assessing patient stability and providing resuscitation. Once the patient is stable, the focus can turn to localization and therapy.

The initial diagnostic workup of GI bleeding involves answering two questions: Is the GI bleed acute or chronic? Is the bleeding source from the upper GI tract (mouth to ligament of Treitz) or the lower GI tract (jejunum to anus)? Acute GI bleed usually stops spontaneously; however in 25% of cases therapy is required. Chronic GI bleeds are often occult and do not require urgent therapy.

Symptoms and Signs

Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleed

Patients usually present inmiddle or older age with a pertinent medical history (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent [NSAID] therapy, peptic ulcer disease, alcoholism, prior upper GI surgery, recent vomiting, portal hypertension), “coffee ground” emesis (previous bleed), hematemesis (ongoing bleed), melena (shiny, pitch-black stool; occurs after blood has been in the GI tract for ≥4 hours), and possibly shock (massive bleed). Hemoptysis is a nonspecific complaint, often implicating tracheobronchial lesions.

Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleed

Although there may be some overlap of symptoms in upper and lower GI bleeding cases, patients with acute lower tract bleeding usually present in older age with maroon stools or bright red blood per rectum; melena is possible if the lesion is relatively proximal.

Chronic Gastrointestinal Bleed

Chronic upper and lower GI bleeds present with fatigue and anemia (nonspecific) and occult fecal blood (lower or upper GI bleed), and possibly with a history of previous bleed. Initial workup is nonemergent and usually involves endoscopy.

Differential Diagnosis

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleed

Pyloroduodenal ulcer, gastritis, esophageal varices, Mallory-Weiss tear, gastric ulcer (usually antrum or lesser curvature), esophagitis with or without hiatal hernia, carcinoma, and hemobilia (patients with biliary tract tumors and/or percutaneous biliary drain).

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleed

Lower GI bleed is usually colonic in origin; however, 10-25% may originate in the small bowel. Top three causes are colorectal cancer (first cause of chronic colorectal

bleed); diverticular disease (often the culprit in acute bleed; bleeding from right-sided diverticulum more common; resolves spontaneously in 80% of cases; however, rebleeds in 25%); and angiodysplasia (second cause of chronic, intermittent bleeding; 15% massive; often multiple and in ascending colon, easily missed on angiography; usually rebleeds and therefore requires resection). Other possibilities include hemorrhoids; inflammatory bowel disease; Meckel’s diverticulum (consider in children and young adults); invasive enterocolitis (Salmonella, Shigella); vasculitis (e.g., polyarteritis nodosa); small bowel tumors (leiomyomas a common cause of episodic GI bleed in young adult, metastasis in older patients); trauma; vasculoenteric fistula; or brisk upper GI bleed.

bleed); diverticular disease (often the culprit in acute bleed; bleeding from right-sided diverticulum more common; resolves spontaneously in 80% of cases; however, rebleeds in 25%); and angiodysplasia (second cause of chronic, intermittent bleeding; 15% massive; often multiple and in ascending colon, easily missed on angiography; usually rebleeds and therefore requires resection). Other possibilities include hemorrhoids; inflammatory bowel disease; Meckel’s diverticulum (consider in children and young adults); invasive enterocolitis (Salmonella, Shigella); vasculitis (e.g., polyarteritis nodosa); small bowel tumors (leiomyomas a common cause of episodic GI bleed in young adult, metastasis in older patients); trauma; vasculoenteric fistula; or brisk upper GI bleed.

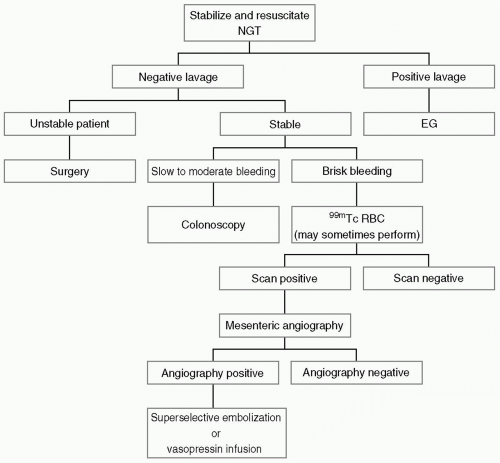

Clinical Workup and Diagnostic Strategy (Fig. 30-1)

Before considering imaging studies, the patient should be resuscitated and stabilized if necessary. Patients who cannot be stabilized often require emergency surgery. Serial hematocrits should be drawn. Because most patients receive intravenous (IV) fluid resuscitation, a fall in hematocrit is often observed during the clinical course unless blood transfusions are given. If acute upper GI bleeding is a possibility, then a nasogastric tube (NGT) should be placed. Large-bore (34 F) oro- or nasogastric tube lavage sensitively and specifically identifies acute or subacute upper GI bleed (repeated pink or red aspirates after clots are evacuated). Rare false positives occur when there is massive lower GI bleed, and occasional false negatives occur with duodenal bleeds. NGT aspirate should be bilious to reduce false negatives.

Figure 30-1. Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding diagnostic algorithm. NGT, nasogastric tube; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy;99mTc RBC, 99mTechnetium red blood cell scan. |

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleed.

Patients with upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding are referred for endoscopy, which identifies a source in more than 95% of patients and is the primary therapeutic measure. Treatment is with electrocautery, injection sclerotherapy, or banding. Advanced radiologic studies are usually not necessary for diagnosis or therapy. However, in situations where a UGI source cannot be identified with endoscopy or is difficult to reach (such as a duodenal ulcer), arteriography may be used.

Lower Gastrointestinal Bleed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree