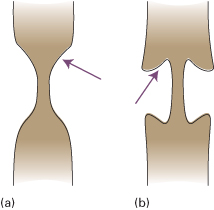

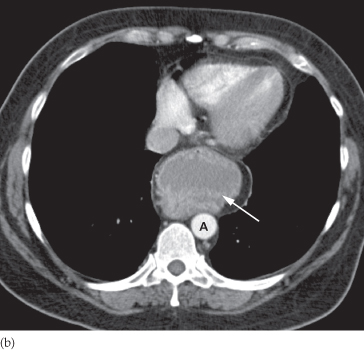

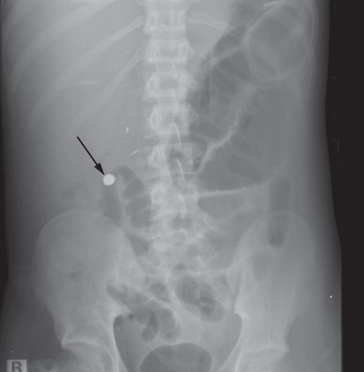

Fig. 6.2 Filling defects in the bowel. (a) Intraluminal. (b) Intramural; note the sharp angle (arrow) made with the wall. (c) Extramural; there is a shallow angle (arrow) with the wall of the bowel.

OESOPHAGUS

Imaging Techniques

Plain Films

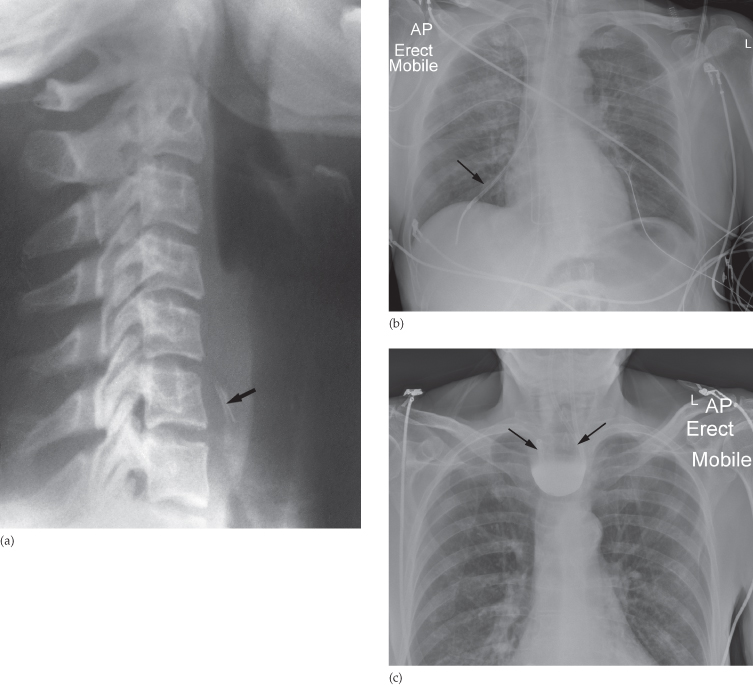

Plain films do not normally show the oesophagus unless it is very dilated (e.g. achalasia), but they are of use in demonstrating an opaque foreign body such as a bone lodged in the oesophagus (Fig. 6.4a). Plain films are also used to check the position of a nasogastric tube, to ensure that the tube travels down through the oesophagus and into the stomach, rather than down into one of the main bronchi or an oesophageal pouch (Fig. 6.4b, c).

Fig. 6.4 (a) Foreign body in the oesophagus. Lateral view of the neck showing a chicken bone (arrow) lodged in the upper end of the oesophagus. (b) A nasogastric tube has been placed down the right main bronchus (arrow). (c) A nasogastric tube has coiled within an oesophageal pouch (arrows). Note that barium has been used to demonstrate the pouch.

The barium swallow is the standard contrast examination employed to visualize the oesophagus. The use of CT and endoscopic ultrasound is limited to the assessment of oesophageal carcinoma.

Barium Swallow Examination

The patient swallows a gas-producing agent to distend the oesophagus, followed by barium, and its passage down the oesophagus is observed on a television monitor. Films are taken with the oesophagus both full of barium to show the outline, and following the passage of the barium to show the mucosal pattern.

The oesophagus has a smooth outline when full of barium. When empty and contracted, barium normally lies in between the folds of mucosa, which appear as three or four long, straight, parallel lines (Fig. 6.5).

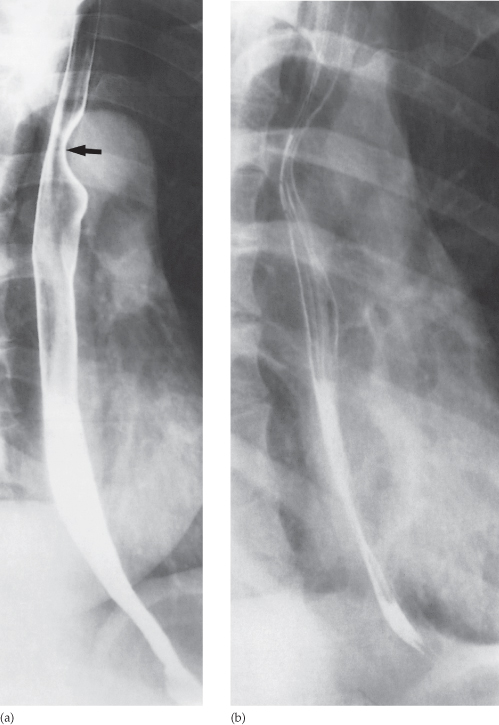

Fig. 6.5 Normal oesophagus. (a) Full of barium to show the smooth outline and indentation made by the aortic arch (arrow). (b) Film taken after the main volume of barium has passed, to show the parallel mucosal folds.

Peristaltic waves can be observed during fluoroscopy. They move smoothly along the oesophagus to propel the barium rapidly into the stomach. It is important not to confuse a contraction wave with a true narrowing: a narrowing is constant whereas a contraction wave is transitory. Sometimes the contraction waves do not occur in an orderly fashion but are pronounced and prolonged, giving the oesophagus an undulated appearance (Fig. 6.6). These so-called tertiary contractions usually occur in the elderly, and in most instances they do not give rise to symptoms. Occasionally, tertiary contractions cause dysphagia.

Fig. 6.6 Tertiary contractions (corkscrew oesophagus) giving the oesophagus an undulated appearance.

Endoscopy is the primary investigation in patients with dysphagia. In centres where expert endoscopy is readily available, the indications for barium or water-soluble contrast studies are shown in Box 6.1.

- Swallowing disorders, including confirming or excluding a pharyngeal pouch

- Determining the length of oesophageal strictures

- Assessing possible mild gastro-oesophageal reflu. (although usually done by manometry)

- Assessing the integrity of an oesophageal anastomosis

- Following obesity reduction surgery and anti-reflux surgery

- Demonstrating an oesophagobronchial or pleural fistula

Computed Tomograpphy

Computed tomography is used in the staging of carcinoma of the oesophagus. The primary function of CT is to detect distant disease (e.g. lung, liver or bone metastases), and although it does give information on local staging, this is more accurately performed by endoscopic ultrasound

Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/computed Tomography

In patients with oesophageal carcinoma who have potentially curable disease, an FDG-PET/CT study (see Fig. 6.11) is performed to identify any occult metastases prior to undertaking either surgery or definitive chemoradiotherapy.

Oesophageal Abnormalities

Strictures of the Oesophagus

Causes of strictures of the oesophagus are shown in Box 6.2.

- Oesophageal cancer

- Peptic strictures

- Achalasia

- Corrosive strictures

- Benign tumours (leiomyomas)

- Other mediastinal masses

- Anomalous right subclavian artery

Oesophageal Carcinoma

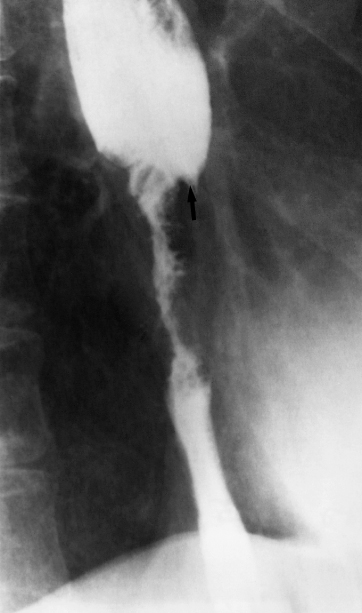

Oesophageal carcinoma is usually first diagnosed at upper GI endoscopy and confirmed by biopsy. Carcinomas usually involve the full circumference of the oesophagus to form a stricture, which can be readily demonstrated at barium swallow examination. It may occur anywhere in the oesophagus, shows an irregular lumen with shouldered edges and is often several centimetres in length (Fig. 6.7). A soft tissue mass may be visible.

Fig. 6.7 Oesophageal carcinoma. There is an irregular stricture with shouldering (arrow) at the upper end.

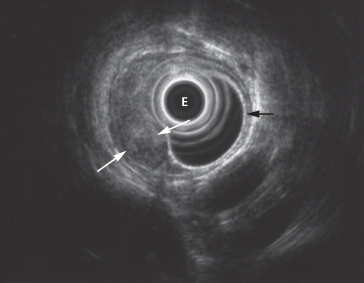

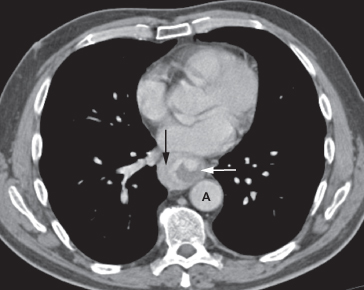

Assessing the extent of the tumour is carried out by endoscopic ultrasound and CT examination. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is able to demonstrate the layers of the oesophageal wall and the surrounding lymph nodes. Oesophageal cancer is seen as a hypoechoic mass and the depth of invasion of the tumour into the oesophageal wall may be assessed (Fig. 6.8). EUS is also used to assess and, if necessary, biopsy, regional lymph nodes to detect potential metastatic disease that might place the patient in a palliative rather than curative pathway. On CT the tumour is seen as a thickening of the oesophageal wall and the length of the tumour can usually be assessed (Fig. 6.9). CT may also show invasion of the mediastinum or adjacent structures, evidence of metastatic spread to lymph nodes, liver or lungs (Fig. 6.10). FDG-PET/CT is used to exclude the presence of occult metastatic disease in patients who are considered potentially curable (either by surgery or radical chemoradiotherapy) after initial evaluation with CT and EUS (Fig. 6.11). Assessment of response to treatment and follow-up of patients with carcinoma of the oesophagus is usually done with CT and endoscopy. FDG-PET/CT is increasingly being used to assess the response of the tumour to chemotherapy or radiotherapy, allowing an early change in therapy in patients who are non-responders.

Fig. 6.8 EUS of oesophageal carcinoma. Note the thickening of the oesophageal mucosa (between the white arrows). A normal part of the oesophagus is indicated by the black arrow. E, endoscope.

Fig. 6.9 Oesophageal cancer on CT. There is thickening and enhancement of the right lateral oesophageal wall (black arrow). In this case, the left wall of the oesophagus is relatively normal (white arrow). A, aorta.

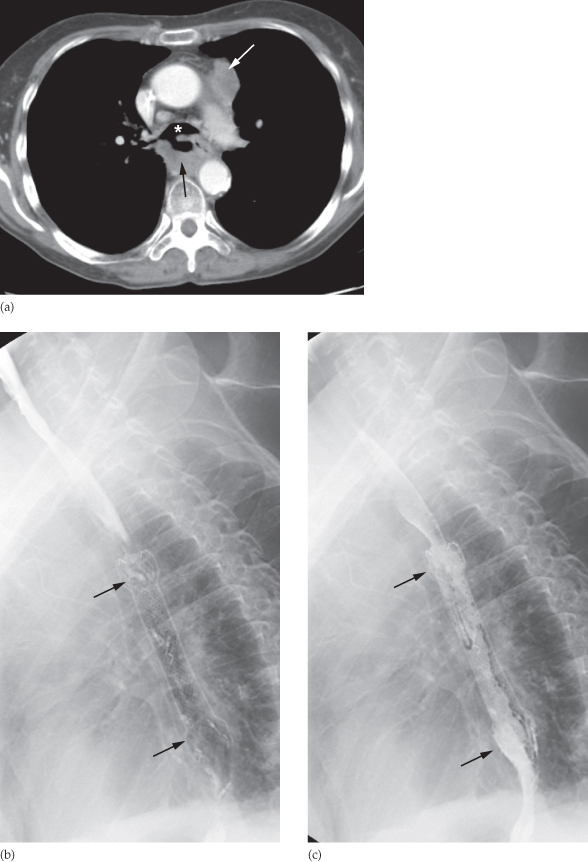

Fig. 6.10 (a) Extensive oesophageal cancer (black arrow) has eroded into the posterior aspect of the carina (*) forming a fistula. Enlarged lymph nodes are present in the anterior mediastinum (white arrow). (b) A stent has been placed across the fistula (arrows). (c) Barium swallow confirms occlusion of the fistula, with no leakage of barium into the bronchial tree.

Fig. 6.11 FDG-PET/CT in a patient with oesophageal carcinoma. The PET component of the study demonstrates the primary tumour (T) at the lower oesophagus. In addition, there is a hot spot over the liver (long arrow).

Peptic Strictures

Peptic strictures can be demonstrated at barium swallow. They are found at the lower end of the oesophagus and are almost invariably associated with a hiatus hernia and gastro-oesophageal reflux and, therefore, the stricture may be some distance above the diaphragm. Peptic strictures are characteristically short and have smooth outlines with tapering ends (Fig. 6.12).

Fig. 6.12 Peptic stricture due to gastro-oesophageal reflux in a patient with a hiatus hernia. There is a short smooth stricture at the oesophagogastric junction with an ulcer crater within the stricture (arrow).

Achalasia

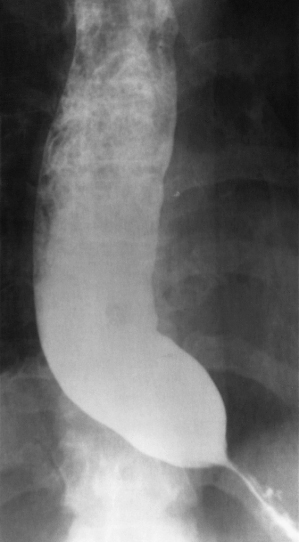

Achalasia is a neuromuscular abnormality resulting in failure of relaxation at the cardiac sphincter, which presents at barium swallow examination as a smooth, tapered narrowing, always at the lower end of the oesophagus (Fig. 6.13). There is associated dilatation of the oesophagus, which often shows absent peristalsis. The dilated oesophagus usually contains food residue and may be visible on the plain chest radiograph. The lungs may show consolidation and bronchiectasis from aspiration of the oesophageal contents. The stomach gas bubble is usually absent because the oesophageal contents act as a water seal, but this sign is not diagnostic of achalasia as it is seen in other causes of oesophageal obstruction and can occasionally be observed in healthy people.

Fig. 6.13 Achalasia. The very dilated oesophagus containing food residues shows a smooth narrowing at its lower end.

Corrosive Strictures

Corrosive strictures are the result of swallowing corrosives such as acids or alkalis. They are long strictures that begin at the level of the aortic arch. As with other benign strictures, they are usually smooth with tapered ends on barium swallow examinations, but may be irregular (Fig. 6.14).

Benign Tumours

Leiomyomas cause a smooth, rounded indentation into the lumen of the oesophagus. A soft tissue mass may be seen in the mediastinum indicating extraluminal extension.

Other Medistinal Masses

Mediastinal masses (e.g. lymphadenopathy secondary to lymphoma or lung cancer) can cause extrinsic compression and narrowing of the oesophagus.

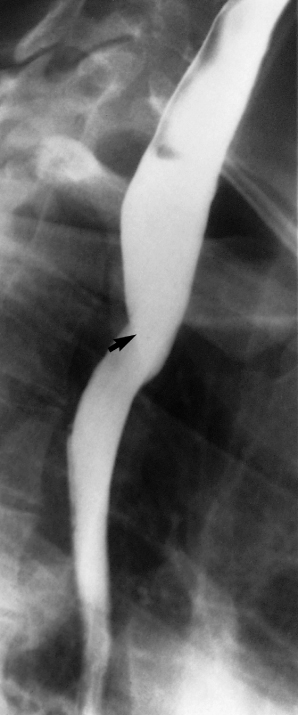

Anomalous Right Subclavian Artery

An anomalous right subclavian artery, which, instead of coming from the innominate artery, arises as the last major branch from the aortic arch, gives rise to a characteristic short, smooth narrowing as it crosses behind the upper oesophagus (Fig. 6.15).

Fig. 6.15 Anomalous right subclavian artery. There is a localized indentation caused by the anomalous artery as it passes behind the oesophagus (arrow).

Dilatation of the Oesophagus

There are two main types of oesophageal dilatation – obstructive and non-obstructive:

- Dilatation due to obstruction is associated with a visible stricture. The patient with a carcinoma usually presents with dysphagia before the oesophagus becomes very dilated. On the other hand, a markedly dilated oesophagus indicates a very longstanding condition, usually achalasia or occasionally a benign stricture.

- Dilatation without obstruction occurs in scleroderma. The disease involves the oesophageal muscle, resulting in dilatation of the oesophagus, which resembles an inert tube with no peristaltic movement so that barium does not flow from the oesophagus into the stomach unless the patient stands upright.

Other Abnormalities of the Oesophagus

An oesophageal web is a thin, shelf-like projection arising from the anterior wall of the cervical portion of the oesophagus and can only be seen when the oesophagus is full of barium (Fig. 6.16). A web may be an isolated finding, but the combination of a web, dysphagia and iron deficiency anaemia is known as Plummer–Vinson syndrome.

Fig. 6.16 Oesophageal web. There is a shelf-like indentation (arrow) from the anterior wall of the upper oesophagus.

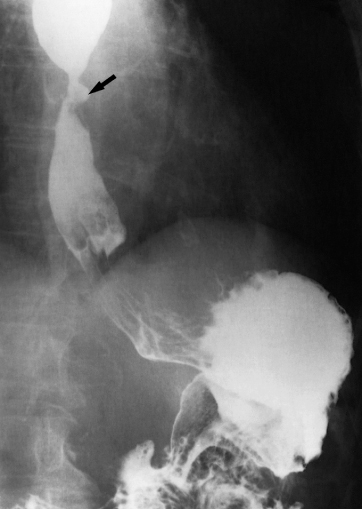

Oesophageal diverticula are saccular outpouchings, which are often seen as chance findings, in the intrathoracic portion of the oesophagus. One type of diverticulum, the pharyngeal pouch or Zenker’s diverticulum (Fig. 6.17) is important as it may give rise to symptoms caused by retention of food and pressure upon the oesophagus. A pharyngeal pouch arises through a congenital weakness in the inferior constrictor muscle of the pharynx and comes to lie behind the oesophagus near the midline. It may reach a very large size and can cause displacement and compression of the oesophagus.

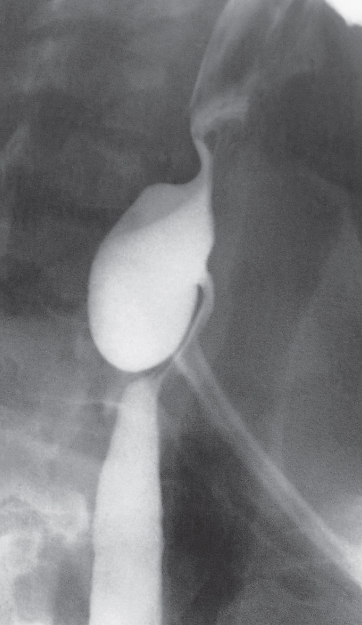

Fig. 6.17 Pharyngeal pouch (Zenker’s diverticulum). The pouch lies behind the oesophagus, which is displaced forward.

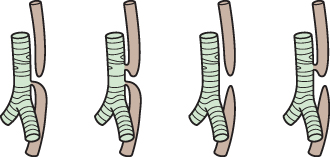

In oesophageal atresia, the oesophagus ends as a blind pouch in the upper mediastinum. Several different types exist (Fig. 6.18), but the most frequent is for the upper part of the oesophagus to be a blind sac with a fistula between the lower segment of the oesophagus and the tracheobronchial tree. A plain abdominal film will show air in the bowel if a fistula is present between the tracheobronchial tree and the oesophagus distal to the atretic segment.

Fig. 6.18 Diagram of the various types of oesophageal atresia. The first two types also have an oesophagotracheal fistula distal to the atretic segment and will show air in the stomach.

The diagnosis of oesophageal atresia is made by passing a soft tube into the oesophagus and showing that the tube holds up or coils in the blind-ending pouch. The use of contrast agents is potentially dangerous because the contrast may cause respiratory problems if it spills over into the trachea.

STOMACH AND DUODENUM

Imaging Techniques

Barium Meal Examination

Barium meal examination is now rarely performed as it has been superseded by endoscopy. The usual technique involves instructing the patient to fast for at least 6 hours prior to the examination. The stomach is distended with a gas-producing agent, and an intravenous injection of a short-acting smooth muscle relaxant is often given. The patient drinks about 200 mL of barium. Films are taken in various positions with the patient both erect and lying flat, so that each part of the stomach and duodenum is shown distended by barium and also distended with air but coated with barium to show the mucosal pattern (Fig. 6.19). The duodenal cap or bulb arises just beyond the short pyloric canal, and the duodenum forms a loop around the head of the pancreas to reach the duodenojejunal flexure. Diverticula arising beyond the first part of duodenum are a common finding and are usually without clinical significance (Fig. 6.20).

Fig. 6.19 Normal stomach and duodenum on double-contrast barium meal. On this supine view, barium collects in the fundus of the stomach. The body and the antrum of the stomach together with the duodenal cap and loop are coated with barium and distended with gas. Note how the fourth part of the duodenum and duodenojejunal flexure are superimposed on the body of the stomach.

Although contrast studies are now less useful in the diagnosis of mucosal abnormalities, they still have an important role in functional studies of the upper GI tract or to evaluate any potential anastamotic leak (Box 6.3). For this reason it is usually water-soluble contrast agents that are used, which are more rapidly resorbed than barium and importantly will allow timely susbsequent imaging with CT. A patient who has undergone an upper GI study with barium will probably have to wait for at least 2 weeks for the barium to clear from the bowel before proceeding to CT, in order to avoid artifact.

- Failed gastroscopy

- Assessment of duodenal strictures that cannot be characterized or navigated on endoscopy

- Assessment of functional patency/gastric emptying following gastroenterostomy or anti-obesity surgery

- To confirm or rule out anastomotic leak following gastric surgery (a water-soluble contrast agent)

Computed Tomography

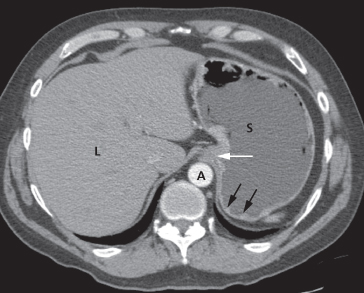

Accurate assessment of the stomach on CT requires good patient preparation and fastidious technique. Firstly, the patient must not eat for 6 hours prior to the CT to ensure that no food residues remain in the stomach, which could obscure or mimic disease. The patient is usually given about 100 mL of tap water to drink (acting as a negative contrast) as well as a smooth muscle relaxant, in order to distend the stomach and duodenum (Fig. 6.21). If the stomach is not distended during the scan, any thickening of the gastric wall could be misinterpreted as being a mass. During the scan, intravenous iodinated contrast medium is injected to demonstrate enhancement of both the normal structures as well as to distinguish the enhancement characteristics of any abnormality.

Fig. 6.21 CT of a normal stomach. The stomach has been distended by oral water contrast and the use of an intravenous smooth muscle relaxant. Some normal rugal folds are still visible (black arrows). Note the gastro-oesophageal junction (white arrow). A, aorta L, liver; S, stomach.

Upper GI endoscopy is widely used as the initial investigation in patients with possible disease of the stomach and duodenum. It enables the mucosa of the stomach and duodenum to be directly inspected and biopsied. The main indications for its use are summarized in Box 6.4.

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Haematemesis and melaena

- Dyspepsia and dysphagia

- Barrett’s oesophagus

- Coeliac disease

- Confirmation and follow-up of malignant tumours

- Injection/clipping/banding to stop bleeding from ulcers or oesophageal varices

- Removal of ingested foreign bodies

- Stenting of upper GI strictures

- Feeding tube placement

Specific Diseases of the Stomach and Duodenum

Peptic Ulcer

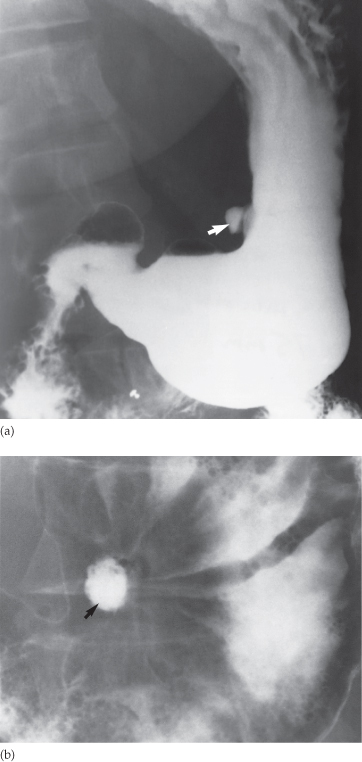

Gastric ulcers may be benign (Fig. 6.22) or malignant so confirmation at gastroscopy is routinely undertaken, whereas duodenal ulcers are almost invariably benign. Ulcers are identified as projections of barium beyond the mucosal profile. With duodenal ulceration, the duodenal cap (bulb) may be very deformed by scarring.

Fig. 6.22 Benign ulcer. (a) In profile, the ulcer (arrow) projects from the lesser curve of the stomach. (b) En face the ulcer (arrow) is seen as a rounded collection of barium.

Gastric Carcinoma

Emphasis is placed on the diagnosis of early gastric cancer, which is confined to the mucosa, as early treatment has a much better prognosis. In the past, high quality barium meal examination has been used as a screening tool in some countries to detect early gastric carcinoma. However, gastroscopy has now almost completely taken over this role.

At barium examination, gastric carcinoma typically produces an irregular filling defect with alteration of the normal mucosal pattern (Fig. 6.23).

Fig. 6.23 Gastric carcinoma on barium study. There are a number of large filling defects in the antrum and body of the stomach.

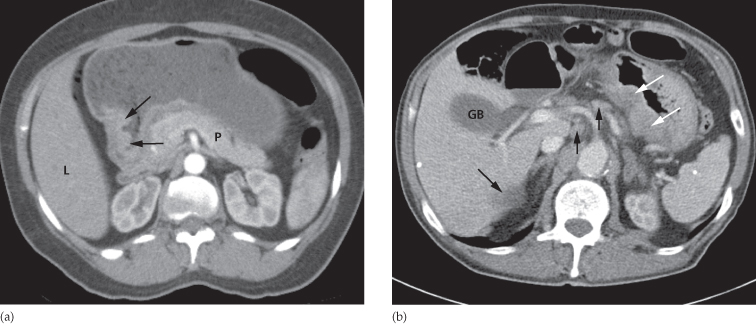

Computed tomography is the main imaging modality for the preoperative staging of patients with gastric cancer as it can show the extent of the primary tumour but also any distant disease (Fig. 6.24). EUS may be used in some cases for local staging and patients will undergo staging laporoscopy prior to curative surgery. FDG-PET/CT does not have a clear role in the primary staging of gastric cancer due to the normal uptake of FDG by the gastric mucosa.

Fig. 6.24 Gastric carcinoma on CT. (a) A focal ulcer is seen arising in the antrum (arrows). (b) In a different patient, there is diffuse thickening of the wall of the stomach (white arrows). Several lymph nodes (short black arrows) and a liver metastasis (long black arrow) are also seen. GB, gall bladder; L, liver; P, pancreas.

Other Gastric Tumours

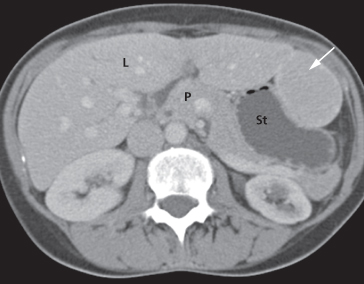

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) arise from the wall of the stomach resulting in a smooth, round, submucosal filling defect, which may ulcerate as the tumour enlarges (Fig. 6.25). GISTs are a group of tumours that are usually benign and well differentiated; they may occur anywhere in the GI tract but 60–70% occur in the stomach.

Fig. 6.25 Gastrointestinal stromal tumour on CT. There is a smooth ovoid mass arising from the anterior wall of the stomach (arrow). This causes an indentation of the stomach. L, liver; P, pancreas; St, stomach.

A leiomyoma is a submucosal tumour which, as well as projecting into the lumen of the stomach, may have a large extraluminal extension that can be easily recognized at CT.

Neuroendocrine tumours of the stomach and duodenum include gastric carcinoid tumours and gastrinomas. Gastrointestinal carcinoid tumours can be found anywhere in the GI tract, particularly the appendix, but can be found incidentally in the stomach often as multiple small (<1 cm) tumours on a background of pernicious anaemia/chronic atrophic gastritis. Occasionally they are seen in association with MEN (multiple endocrine neoplasia) type 1 in association with other endocrine tumours, or as a solitary larger tumour (>3 cm) where they can cause local symptoms of abdominal pain and bleeding as well as the carcinoid syndrome. Gastrinomas usually secrete gastrin, resulting in increased gastric acidity and peptic ulceration. Gastrinomas are often very small and typically enhance brightly in the arterial phase (Fig. 6.26).

Fig. 6.26 Duodenal gastrinoma. The duodenum has been distended using a smooth muscle relaxant and oral water. The tiny gastrinoma is seen as a brightly enhancing lesion in the wall of the duodenum (arrow), on the arterial phase of enhancement. A, aorta; D, duodenal lumen; K, kidney.

Gastric Polyps

Gastric polyps may be single or multiple. They may be sessile or have a stalk. Even with high quality radiographs it is often impossible to distinguish benign from malignant polyps. For this reason, gastroscopy with biopsy or operative removal is invariably carried out on all suspected polyps. Other intraluminal defects within the stomach include food or blood following a haematemesis. Sometimes ingested fibrous material, such as hair, may intertwine forming a ball or bezoar (Fig. 6.27).

Fig. 6.27 CT of a bezoar. The stomach is distended by a large mass of hair mixed with oral contrast (white arrows). The antrum is also distended by the ingested material (black arrow).

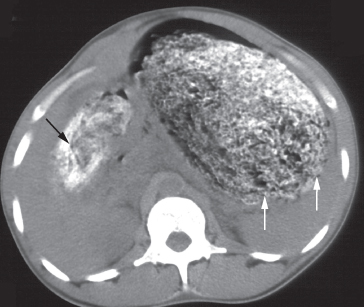

Lymphoma

The stomach is the most frequent site of lymphoma involving the GI tract, either as primary disease or by infiltration from adjacent nodes. The appearance of primary gastric lymphoma is typically of an extensive area of diffuse thickening of the gastric wall (Fig. 6.28). There may be extensive, bulky lymphadenopathy adjacent to the tumour. The appearance may mimic gastric carcinoma.

Fig. 6.28 Gastric lymphoma in the antrum, demonstrated on CT (white arrows). Lymphadenopathy surrounds the inferior vena cava (black arrow). St, stomach; Sp, spleen.

Gastric Outlet Obstruction

In most patients, contrast leaves the stomach within a few minutes of the smooth muscle relaxant wearing off, but in others this only occurs after the patient has been lying on the right side for some time. Prolonged delay in a patient with a dilated stomach containing food residues needs to be explained. In adults, the causes of gastric outlet obstruction are listed in Box 6.5.

- Chronic duodenal ulceration: the diagnosis depends on demonstrating a very deformed, stenosed duodenal cap. It may or may not be possible to identify an actual ulcer crater

- Carcinoma of the antrum

- Duodenal, ampullary and pancreatic carcinoma

- Acute or chronic pancreatitis, including pseudocyst formation

- Poor functional patency of a gastroenterostomy

- Pyloric stenosis in infants

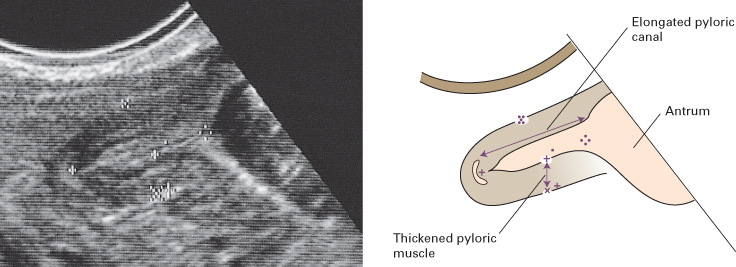

In infants, pyloric stenosis is by far the commonest cause of gastric outlet obstruction. Often, the diagnosis is made clinically and can be confirmed with ultrasound, which has superseded barium meal. Ultrasound shows a thickened, elongated pyloric canal (Fig. 6.29).

Fig. 6.29 Pyloric stenosis. Ultrasound scan in a neonate showing a thickened, elongated pyloric canal.

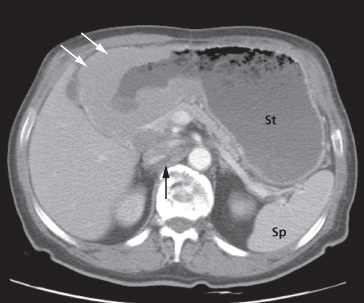

Hiatus Hernia

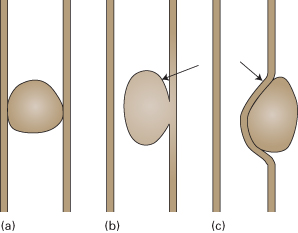

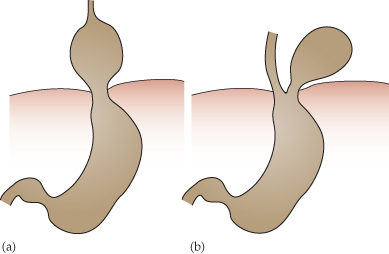

A hiatus hernia is a herniation of the stomach into the mediastinum through the oesophageal hiatus in the diaphragm. It is a common finding. Two main types of hiatus hernia exist: sliding and rolling. An alternative name for a rolling hernia is ‘para-oesophageal’ (Fig. 6.30).

Fig. 6.30 Hiatus hernia. (a) Sliding: a portion of the stomach and the gastro-oesophageal junction are situated above the diaphragm. (b) Rolling or para-oesophageal: the gastro-oesophageal junction is below the diaphragm.

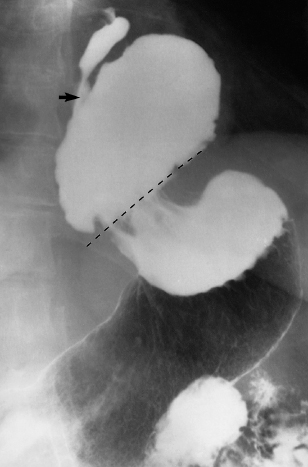

The commoner type is the sliding hiatus hernia, where the gastro-oesophageal junction and a portion of the stomach are situated above the diaphragm (Fig. 6.31). The cardiac sphincter is usually incompetent, so reflux from the stomach to the oesophagus occurs readily and this may cause oesophagitis, ulceration or peptic stricture. A small sliding hernia may be demonstrated in most people during a barium meal examination, provided that enough manoeuvres have been undertaken to increase intra-abdominal pressure. It is, therefore, difficult to assess the significance of a small hernia with little or no reflux.

Fig. 6.31 Sliding hiatus hernia. The fundus of the stomach and the gastro-oesophageal junction (arrow) have herniated through the oesophageal hiatus and lie above the diaphragm (dotted line).

In a rolling or para-oesophageal hernia, the fundus of the stomach herniates through the diaphragm, but the oesophagogastric junction often remains competent below the diaphragm.

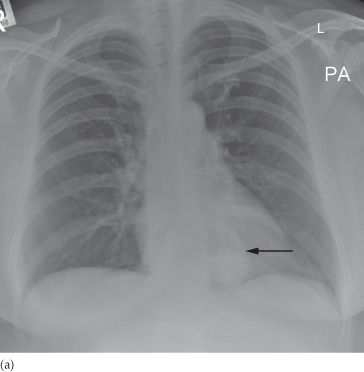

A large hernia, particularly one of the para-oesophageal type, may not be reduced when the patient is in the erect position. In these instances the hiatus hernia will be seen on chest films and on CT (Fig. 6.32).

Fig. 6.32 Hiatus hernia. (a) Chest x-ray demonstrating a rounded mass (arrow) with an air–fluid level projected behind the heart shadow. (b) CT in the same patient demonstrating the fundus of the stomach extending up into the posterior mediastinum (arrow). A, aorta.

SMALL INTESTINE

The small bowel remains one of the most difficult organs to evaluate. Unlike the stomach and duodenum, fibreoptic endoscopy is difficult to perform due to the long and tortuous nature of the small intestine. Imaging studies (contrast studies, CT, MRI) therefore play a pivotal role in the evaluation of the small bowel. Capsule endoscopy, which requires the patient to ingest a tiny capsule containing a camera, may be helpful in some cases (Fig. 6.33). The capsule is ultimately passed with the faeces and may provide information concerning luminal or mural abnormalities of the small bowel. Small bowel endoscopy (enteroscopy) is becoming increasing available but is still only used in very specific circumstances.

Fig. 6.33 A capsule endoscope within a loop of small bowel (arrow). A nasogastric tube is also present, projected over the left upper quadrant.

Imaging Techniques

Standard imaging techniques and their indications are:

- Small bowel follow-through (small bowel meal) (Fig. 6.34

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree