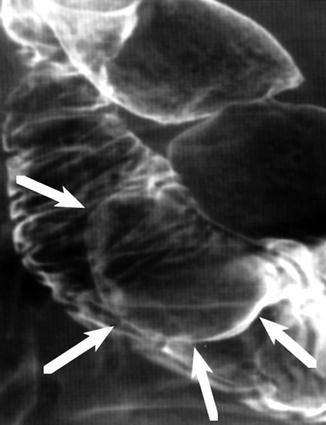

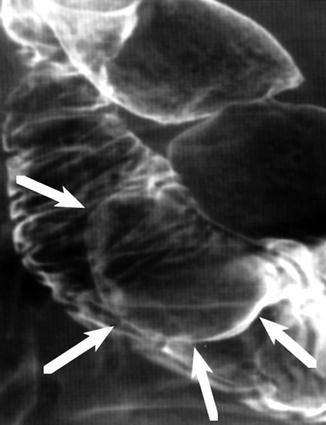

Fig. 31.1

Esophageal pedunculated polyp. Double-contrast barium study: middle esophageal polyp with a very long stalk a) the single down arrow indicates the head of the polyp, the two opposing arrows indicate the stalk; c) the two opposing arrows indicate the stalk

Papillomas are more common (5 % of esophageal tumors) than adenomas and are composed of a fibrovascular core covered by squamous epithelium. Reflux esophagitis and papillomavirus infection are predisposing factors. They are usually solitary and small (not exceeding 1.5 cm) lesions and often located on the distal third of the esophagus. Papillomas typically represent an incidental finding in asymptomatic patients on barium studies and endoscopic examinations, where they appear as small, polypoid, pedunculated lesions with a smooth to slightly lobulated surface. Also papilloma represents a precancerous condition.

Leiomyomas constitute 50 % of benign tumors of the esophagus, originating in muscle tissue of the wall. Over 60 % of leiomyomas are located in the lower third, where they commonly appear as large submucosal masses, between 2 and 8 cm in size, with exophytic, intraluminal, or rarely circumferential growth pattern. The patient is asymptomatic with small lesions, but when the tumor reaches sufficient size, the normal mobility of the bowel is affected and swallowing disorders may occur.

On double-contrast barium X-ray, leiomyoma has the typical appearance of an intramural lesion producing rounded or oval smooth filling defects in anteroposterior and posteroanterior projections, while in latero-lateral views the margins often form nearly a right angle with the esophageal wall. The mucosa is smooth, without ulcers although calcifications into the lesion may be present. On CT, the tumor appears as a homogeneous soft tissue mass, and after intravenous contrast, the enhancement is similar to that of normal muscle tissue wall. Submucosal lesions are less common: fibromas, lipomas, and hemangiomas (Green et al. 2002).

31.2.2 Malignant Tumors

Malignant tumors of the esophagus are carcinomas and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). Sarcomas, lymphomas, and metastases are less common. Esophageal cancer is the third most common cancer of the GIT, with an overall 5-year survival rate less than 10 %. There are two histologic variants: squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, evenly distributed between the middle and lower third of esophagus, where nearly three quarters of all esophageal cancers are located.

Predisposing factors to squamous cell carcinoma are achalasia, stenosis from caustics, previous head and neck cancers, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, radiation, and tylosis; with adenocarcinoma, progression to dysplasia and cancer in Barrett esophagus is known.

Dysphagia is the most frequent symptom in patients with esophageal cancer. Less common presenting symptoms include odynophagia, anorexia, weight loss, chest pain on swallowing due to mediastinal structures infiltration, and anemia related to chronic oozing of blood; hematemesis is a rare occurrence in case of aortoesophageal fistula. Some patients may have hoarseness due to direct infiltration of the larynx or recurrent laryngeal nerve. Cough, when present, should raise the suspicion of trachea-esophageal or esophago-bronchial fistula. It seems evident that these are nonspecific symptoms often present in elderly patients as consequences of functional disorders occurring with age or as expression of cerebrovascular diseases (Green et al. 2002).

The staging of esophageal cancer is assessed with the TNM system as developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC); the histologic types of esophageal cancer are not taken into account (Fleming et al. 1997). The esophagus is divided into four anatomic regions for classification, reporting, and staging purposes. The cervical portion extends from the cricoid cartilage to the thoracic inlet. The thoracic esophagus extends from the thoracic inlet to the gastroesophageal junction and is divided into upper, mid, and lower. The upper thoracic esophagus extends from the thoracic inlet to the carina, the mid-thoracic esophagus from the carina to the gastroesophageal junction, and the lower thoracic and abdominal esophagus, which measures approximately 8 cm in length, including the intra-abdominal portion of the gastroesophageal junction.

Treatment strategy depends on the depth of parietal infiltration: patients with T1 or T2 tumors may be candidates for surgical therapy, whereas patients with T3 or T4 tumors are frequently offered preoperative chemotherapy or combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

According to the current AJCC classification system, locoregional lymph nodes are defined on the basis of the location of the primary esophageal tumor. The identification of metastases is important in treatment planning. According to the AJCC, distant metastases are subdivided into M1a and M1b subcategories, with M1a indicating metastases to cervical or celiac axis lymph nodes and M1b indicating metastases to distant sites.

Endoscopic ultrasound is considered the most accurate imaging modality currently available for primary tumor staging (T staging) in patients with esophageal cancer. The esophageal wall is visualized as five alternating layers of differing echogenicity. The first layer is hyperechoic and represents the interface between balloon and superficial mucosa. The second layer is hypoechoic and represents the lamina propria and muscularis mucosae. The third layer is hyperechoic and represents the submucosa. The fourth layer is hypoechoic and represents the muscularis propria. The fifth layer is hyperechoic and represents the interface between the serosa and surrounding tissues. Recently, endoscopic ultrasound performed with high-frequency ultrasound probes has shown promising results in helping distinguish mucosal (T1m) from submucosal (T1sm) invasion. The tumor is recognized as a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass, which disrupts the normal stratification of the wall. Only a limited number of metastatic lymph nodes can be recognized with endoscopic ultrasound (Lightdale and Kulkarni 2005).

The double-contrast barium X-ray is considered the best technique for identifying early cancer, with a limit of non-differentiation between T2 and T3. The early lesion may present with different aspects: nodular, plaque, polypoid, and ulcerated. In the advanced stage, lesions may appear as diffuse infiltrating, polypoid, ulcerative, or varicose. Infiltrating lesions are characterized by irregular narrowing with stenosis of the esophageal lumen, whereas the overlying mucosa may be ulcerated or nodular with proximal and distal sharp edges. The polypoid tumor appears as a large mass projecting into the lumen inducing esophageal obstruction; the ulcerated surface is expressive of tumor necrosis. In the ulcerated form, a large well-defined ulcer replaces the mass. In the varicoid lesion, the vector growth is submucosal, resulting in a thickening of the folds, which appear irregular and tortuous. In the double-contrast barium X-ray, extrinsic footprints on esophagus, expression of nodal metastases, and fistulas within the bronchial tree are found (Berger and Scott 2004).

The normal esophageal wall is usually less than 3 mm thick at double-contrast CT when the esophagus is distended. Asymmetric thickening of the esophageal wall is a primary but nonspecific CT finding of esophageal cancer. CT is unable to adequately help differentiate between T1, T2, and T3 diseases, whereas it is possible to differentiate between T3 and T4, a distinction that is important when considering the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy. The CT criteria for T4 identification include loss of fat planes between the tumor and adjacent structures in the mediastinum and displacement or indentation of other mediastinal structures (Fig. 31.2). Aortic invasion is suggested if 90° or more of the aorta is in contact with the tumor or if there is obliteration of the triangular fat space between the esophagus, aorta, and spine adjacent to the primary tumor. A tracheobronchial fistula or tumor extension into the airway lumen is a definite sign of tracheobronchial invasion. Displacement of the trachea or bronchus or indentation of the posterior wall of the trachea or bronchus by the tumor has been proved accurate in predicting tracheobronchial invasion. Pericardial invasion is suspected if pericardial thickening or pericardial effusion is seen. In cachectic patients, especially after neoadjuvant therapy, the cleavage planes of the fat may not be reliable, with a real difficulty in staging. An important limitation of CT in staging esophageal cancer is its lack of sensitivity for detecting lymph node metastases, since even a normal-sized lymph node might contain microscopic metastatic foci that are beyond the level of detection offered by CT. CT has an established role in the detection of distant organ metastases (M1b) (Kim et al. 2009; Kwon et al. 2005). CT plays a key role in follow-up after surgery and in planning and follow-up of implants, thanks to the MPR and 3D reconstructions in various planes (Fig. 31.3a, b).

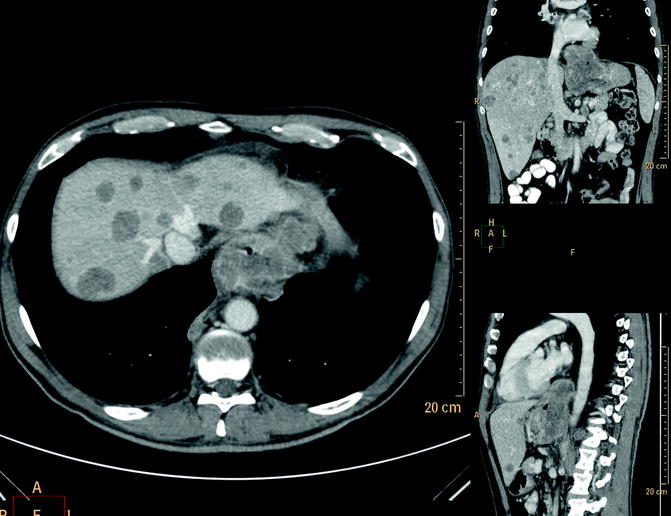

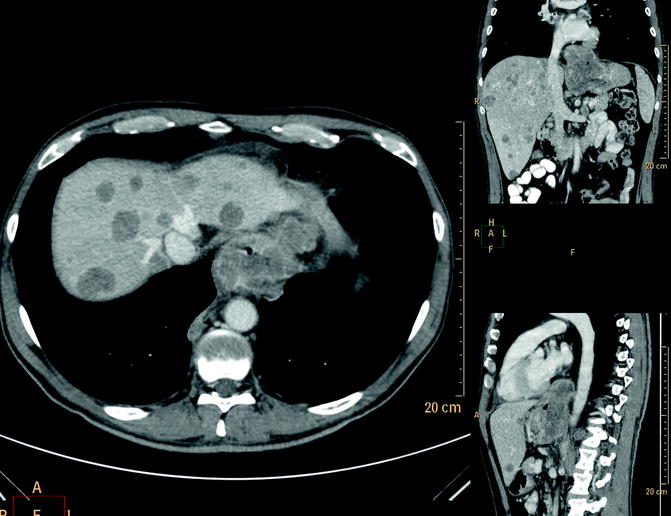

Fig. 31.2

Distal esophageal cancer. Multi-detector CT with m.d.c. IV, axial scan, and MPR reconstruction: large and inhomogeneous solid mass located at the distal half of the esophagus infiltrating perivisceral fat and adjacent structures (stage IV), presence of multiple concomitant liver metastases

Fig. 31.3

(a, b) Mid and distal advanced esophageal cancer treated with metal stent. Multi-detector CT with m.d.c. IV and reconstruction MPR (a) and 3D volume rendering (b) esophageal metal stent well deployed and expanded into the mid and distal malignant stricture as a palliative treatment

The long execution time of MRI is a limiting factor in patients with reduced compliance. This method visualizes the primary tumor as an abnormal and asymmetric wall thickening of the esophagus. The superior contrast resolution achieved with MRI would suggest that the technique is likely to be useful in differentiating tumors abutting surrounding structures (stage T3) from direct invasion of tumor into the surrounding tissues (stage T4), and, thanks to innovative diffusion-weighted sequences, it has greater sensitivity than CT in identifying metastatic lymphadenopathy (Riddell et al. 2007).

Although PET has been shown to have a higher sensitivity than CT in the detection of primary esophageal cancer, it is of limited value in assessing T stage because it provides little information on the depth of tumor invasion. The sensitivity and specificity for the detection of locoregional metastases are low (51 and 84 %, respectively). Intense uptake of FDG by the primary tumor commonly complicates interpretation by obscuring the adjacent regional lymph node basins. In contrast, sensitivities as high as 90 % have been reported in the detection of metastatic lymph nodes at distant sites (M1a) and distant metastases (M1b). The differentiation between FDG uptake by peritumoral lymph nodes and that by the primary tumor might be improved with PET-CT, which, at present, is the best imaging modality for the evaluation of therapeutic response to neoadjuvant treatment (Bruzzi et al. 2007).

31.3 Gastric Tumors

Stomach cancer remains the second most common cancer worldwide. While benign forms have no predilection for age, diagnosis at an advanced age is an expression of a missed diagnosis. Carcinoma is recognized as a neoplasm of the elderly, with a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life. However in this group of patients, compared to younger people, the tumor is a distinct clinical pathologic entity with some peculiar elements. In both the non-endemic and endemic lesions, in patients older than 65 years, there is a preponderance of women (male to female ratio of 1.6:1–2.4:1). The site is in the middle and lower third of the stomach; the macroscopic appearance is type IIc (46 %) followed by types I and IIa for early gastric cancer and type III for advanced cancer. Regardless of the stage, several studies have demonstrated that in elderly patients gastric cancer is often a well-differentiated form (papillary and tubular adenocarcinoma), while the poorly differentiated forms represent only 10 % of all cases.

The well-differentiated intestinal-type adenocarcinoma is more frequent in the elderly and usually tends to spread to the liver, while peritoneal carcinomatosis is uncommon.

In advanced forms, the locoregional lymph node involvement is no different than in young patients (high incidence), while in early gastric cancer lymph node involvement is less common than in the young (Saif et al. 2010).

Gastric cancer in aged people is often a hidden injury, responsible for iron-deficiency anemia, expression of chronic oozing blood, associated with a state of malnutrition; these symptoms are nonspecific and are very common in the elderly; they are epiphenomena of a myriad of clinical entities not necessarily related to the location and extent of the cancer. The tumor may not be clinically evident until it reaches a considerable size, causing a mechanical obstruction with involvement of perivisceral loose connective tissue (T4), lymph node, and distant metastasis (Arai et al. 2004).

Therefore, the diagnosis is not easy, especially in non-endemic areas where there is no screening strategy.

Endoscopic ultrasound is considered to be the most accurate imaging modality currently available for primary tumor staging (T staging). The double-contrast barium X-ray is considered the best technique for identifying early cancer, despite its low specificity. CT plays a key role in the staging and during and after medical therapy and surgery. PET, in particular PET-CT, is the best imaging modality for evaluation of therapeutic response to treatment.

MRI has the same advantages as CT but the long execution time is a limiting factor in patients with reduced compliance.

31.3.1 Benign Tumors

Benign tumors represent only 10 % of all tumors, with a peak incidence between 40 and 60 years; therefore, their presence in the elderly is an expression of misdiagnosis in earlier years. The benign tumors are usually asymptomatic, although they may be responsible for iron-deficiency anemia.

Epithelial forms, hence mucosal lesions, include hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps: while the former are not precancerous lesions, adenomatous polyps have a demonstrated risk of malignant degeneration.

Despite enormous advances in diagnostic imaging, the final diagnosis remains histological.

The double-contrast barium X-ray allows identification of some distinctive features: hyperplastic polyps are smooth, soft sessile lesions, less than 1 cm in size, often with multiple locations but more frequent at fundus and gastric body; adenomatous polyps are sessile or pedunculated, polylobulated, larger than 1 cm, usually single, and localized in the gastric antrum (Fig. 31.4a, b) (Gabrielsson 1972).

Fig. 31.4

(a, b) Gastric polyps. Double-contrast barium study: single pedunculated polyp (a) and multiple and different-sized adenomatous polyps (b) of the gastric body. The arrows indicate the polyps

If they reach a considerable size, on CT examination both types of polyps may appear as intraluminal round masses originating from the mucosa, with soft tissue density (Kim et al. 2006).

Leiomyomas, more frequent in the sixth decade of life, are benign tumors originating from the submucosa. The size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters, and when they reach a considerable diameter, superficial ulceration may appear. On double-contrast barium X-ray, most gastric leiomyomas appear as a well-defined submucosal mass with smooth edges and forming an acute or obtuse angle with the adjacent wall. If mucosal ulceration is present, it appears as a central crater filled with barium (“bull’s-eye” or “target” appearance). On CT examination leiomyomas appear as well-encapsulated masses with homogeneous enhancement; the presence of hyperdense streaks or groups of calcifications in the context is also possible (Houghton and Wang 2006). Only 5 % of all gastrointestinal lipomas are in the stomach. CT is the technique of choice for the diagnosis, since it recognizes the typical negative attenuation (Fig. 31.5a–d) (Houghton and Wang 2006).

Fig. 31.5

(a–d) Gastric lipoma. Multi-detector CT with m.d.c. IV, axial scan: smooth, well-marginated, homogeneous, fatty dense mass of the gastric fundus and body (a). Vascular pedicle well visualized in MPR/MIP reconstructions (b, c). Ultrasound appearance (d)

31.3.2 Malignant Tumors

Adenocarcinoma is by far the most common gastric malignancy, representing over 95 % of malignant tumors of the stomach. Less frequent tumors include lymphomas (4 %), carcinoid tumors (3 %), leiomyosarcomas (2 %), and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) (1 %) (Horton and Fishman 2003).

Gastric cancer affects predominantly the elderly and almost 70 % of people with gastric cancer are over 65 years of age. It is an aggressive tumor with a 5-year survival rate of less than 20 %; however, if it is diagnosed at “early gastric cancer” stage, the 5-year survival ranges between 70 and 95 %. Atrophic gastritis, pernicious anemia, gastric polyps, partial gastric resection, and Mènètrier syndrome are predisposing factors. The most common symptoms are abdominal pain and weight loss. Bleeding is a less common manifestation, which appears with vomiting blood or dark stool; light bleeding can go unnoticed or appear only with iron-deficiency anemia. Other symptoms may include dysphagia, dyspepsia, early satiety or lack of appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and weakness (Forman and Goodman 2000).

Most gastric carcinomas are adenocarcinomas originating from the glandular epithelium of the gastric mucosa, mainly distributed between the middle and lower third of the stomach, whereas the diffuse form affects only 10 % of cases. Scirrhous cancer (5–15 % of all gastric cancers) is characterized by a vigorous stromal desmoplastic response, referred to as “linitis plastica” carcinoma of the stomach. It typically originates from the distal half of the stomach, near the pylorus, and gradually extends in a cranial direction; in advanced cases the entire stomach is infiltrated by the tumor. With regard to depth of mural invasion, it is possible to distinguish two forms of cancer:

Early gastric cancer, limited to the mucosa or submucosa without invasion of lymph nodes

Advanced gastric cancer with invasion of the muscularis propria

Tumor stages are defined according to the AJCC staging system: T1, tumor invades lamina propria or submucosa; T2, tumor invades muscularis propria or subserosa; T3, tumor penetrates serosa (visceral peritoneum) without invasion of adjacent structures; and T4, tumor invades adjacent structures (liver, pancreas, colon, etc.).

Lymphatic dissemination is found in 74–88 % of patients with stomach cancer, in relation to the abundance of lymphatic vessels in the bowel; the frequency of lymphatic metastases correlates well with the size and depth of penetration of the tumor. The most common metastatic site is the liver; peritoneal surfaces and locoregional or distant lymph nodes are frequent. Central nervous system, pulmonary, renal, and bone metastases occur but are less frequent. The advanced gastric cancer may have a peritoneal dissemination related to the tumor cell seeding of the visceral peritoneum (Greene et al. 2002). Surgery remains the only potentially curative treatment. In elderly patients undergoing therapeutic intervention, morbidity (30–40 %) and mortality (<10 %) rates are comparable to those in younger patients (Martella et al. 2005).

The double-contrast barium X-ray shows a high diagnostic accuracy in identifying gastric tumors: the “early gastric cancer” typically appears as plaque-like elevation, mucosal nodularity, and/or shallow areas of ulceration or as shallow ulcer craters with nodularity of the adjacent mucosa and clubbing or fusion of radiating folds, due to the infiltration of the tumor into the adjacent folds. In advanced stages carcinoma occurs with different patterns: polypoid, lobulated, or fungoid mass often ulcerated and with irregular margins protruding into the gastric lumen. The gastric folds end abruptly in the vicinity of the lesion and the wall is rigid.

The ulcerated carcinomas are characterized by the presence of an irregular ulcer crater, eccentrically located into the mass, with scalloped, angled, or stellate edges. The gastric folds converging at the ulcer may be truncated, nodular, or fused together as a result of tumor infiltration. Infiltrating carcinomas manifest with an irregular stenosis of the stomach and are associated with spiculated mucosal nodularity; some lesions may have polypoid or ulcerated components (Ogata et al. 1999).

Endoscopic ultrasonography is currently the most reliable method available for preoperative determination of T stage, with a diagnostic rate between 64.8 and 93 %. A characteristic sonographic appearance shows pseudokidney sign visualized as a hypoechoic, inhomogeneous mass, invading the gastric wall with a high color-Doppler signal and colliquative intralesional areas (Tsendursen et al. 2006).

Multi-detector CT with water (hydro-CT) and gas filling the stomach, use of protocols with thin-section collimation, and multiplanar or 3D reconstructions all increase quality of CT and have been reported to provide better detail for T staging, making CT the principal imaging technique for gastric carcinoma staging (Chen et al. 2007).

The lesion may occur with different aspects according to the location, size, and macroscopic appearance: small and superficial lesions in a collapsed stomach can be disregarded, whereas with a large tumor the entire stomach wall is abnormally enhanced and the abnormal enhancement is accompanied by wall thickening, linear or reticular structures in the fatty layer surrounding the stomach, and the presence of enlarged and colliquated lymph nodes (Kumano et al. 2005).

Virtual gastroscopy performed with multi-detector CT can contribute to the detection and characterization of early gastric cancer. This technique depicts the tumor mass in the same way as gastroscopy, clearly demonstrating elevated and depressed lesions but poorly demonstrating flat lesions and gastric angle tumors.

The use of 2D MPR and CT gastrography is a promising method in the preoperative evaluation of advanced gastric cancer. Two-dimensional MPR allows accurate staging of gastric cancer and provides extraluminal information such as the presence of lymphadenopathy and distant metastasis. The ability to visualize an abnormality in multiple planes increases confidence and helps to better characterize the lesion. Virtual gastroscopy including transparency rendering performed with the volume rendering technique allows detection of subtle mucosal changes and differentiation of mucosal lesions from submucosal lesions in the same manner as conventional gastroscopy (Kim et al. 2007).

MRI, thanks to its multiparametric and multiplanar yield, has the same advantages as CT, although it is infrequently used in the study of gastric cancer due to the long acquisition time in noncooperative subjects. On contrast-enhanced MRI the tumor appears as thickening of the bowel wall with hypointense signal on T1-weighted images and hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images; hyperintense foci, expression of necrotic colliquative phenomena, may also appear. Fat-saturated sequences allow a proper assessment of the perivisceral loose connective tissue and presence of lymphadenopathy. The heterogeneous increase of signal after administration of gadolinium is an expression of the heterogeneity of the lesion. Diffusion-weighted sequences play an important role in the identification of metastatic lymph nodes; moreover they are helpful in the differential diagnosis between neoplastic stenosis and stenotic scar (Kinkel et al. 2002).

FDG-PET has been recognized as a useful diagnostic technique in oncology, but experience with evaluation of gastric cancer is limited. It can be particularly useful in evaluating distant lymph node metastases (levels III and IV) and metastases to distant organs (liver, lungs, adrenals, ovaries, and other) (Lim et al. 2006).

The stomach is the most frequent site of gastrointestinal tract involvement by lymphoma (35 % of total), affecting most commonly people aged 50–60 years, with no sex differences in incidence.

Most of these tumors are non-Hodgkin lymphocytic or histiocytic type (90–95 %); mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is a low-grade B-cell lymphoma, and it is thought to be associated with Helicobacter pylori infection (Tucci et al. 2009). On radiology, gastric lymphomas may appear as infiltrating, polypoid, nodular, or ulcerative lesions.

Infiltrative gastric lymphomas manifest as focal or diffuse enlargement of gastric folds due to submucosal spread of tumor; folds may be massively enlarged and often have nodular and distorted contours, so they can be mistaken for a polypoid tumor.

Polypoid gastric lymphomas are composed of one or more lobulated intraluminal masses.

Multiple submucosal nodules ranging in size from several millimeters to several centimeters characterize nodular gastric lymphoma; these submucosal masses may undergo central necrosis and ulceration, producing “bull’s-eye” or “target” lesions.

One or more ulcerated lesions characterize ulcerative gastric lymphoma; the ulcers are more frequently an irregular shape with a nodular appearance of the surrounding mucosa or associated with thickened and irregular folds resulting from lymphomatous infiltration of the stomach wall.

Endoscopic ultrasound has proven to be a very valuable technique for the staging of gastric lymphoma. The sonographic appearance of the tumor can be highly variable from a hypoechoic mass that disrupts the normal mural stratification of the stomach to a selective or diffuse echogenic thickening of the stomach wall.

CT, in particular hydro-CT, is the primary imaging modality for pretreatment evaluation and follow-up of lymphoma. At CT, gastric lymphoma typically appears as circumferential, segmental, or diffuse wall thickening (about 4–5 cm) more conspicuous than in adenocarcinoma, but usually without obstruction (Fig. 31.6a–d). Perigastric adenopathy is common in patients with gastric lymphoma as well as in those with gastric adenocarcinoma. However, adenopathy that extends below the renal hila favors gastric lymphoma over adenocarcinoma as a diagnosis (>40 %). CT is useful in detecting complications such as perforation, extragastric extension, or fistulization. The splenic metastases are suggestive of lymphoma. In patients with gastric MALT lymphoma, the most frequent finding is gastric wall thickening. Such wall thickening is usually minimal and may not be detected on CT, especially if the stomach is not maximally distended. Associated adenopathy is uncommon.

Fig. 31.6

(a–d) Gastric lymphoma and adenocarcinoma. Multi-detector CT with m.d.c. IV, differential diagnosis. Axial scan (a) and coronal reconstruction (b) lymphoma of the gastric antrum, massive and inhomogeneous mural thickening without marked luminal narrowing or dilation of the proximal portion, which are typically seen with carcinomas (c, d)

31.4 Small Bowel Tumors

Although the small intestine alone includes more than 90 % of the mucosal surface of the entire GIT, tumors are rare; only about 3–6 % of all gastrointestinal primary tumors, more “common” but often unrecognized, are the metastases. The most common benign tumor in the elderly is the adenoma, whereas malignancies have a peak incidence between the sixth and seventh decades and are represented by adenocarcinoma (45 %), lymphoma (15 %), and stromal tumors (10 %), including GIST and carcinoid. It is more common in men than in women. The diagnosis is difficult and represents a challenge for the clinician and the radiologist.

Neoplasms are often asymptomatic and if there are any symptoms, they are frequently aspecific (anorexia, weight loss, iron-deficiency anemia, dyspepsia) and in 60–75 % of cases indicative of malignancies. Commonly, the clinical manifestation of cancer is an acute abdominal massive bleeding, perforation, and mechanical ileus (Grassi et al. 2004; Ruiz-Tovar et al. 2009).

Inadequate radiograph or incorrect interpretation of radiographic signs contributes to diagnostic delay. Although endoscopy, videocapsule, and traditional enteroclysis are routine procedures, their usefulness is limited to the study of wall lesions (Albert et al. 2005). In addition, the poor tolerability, due to the long execution time and to the intrinsic difficulties of the procedures, reduces the use in elderly patients.

Ultrasound is often the first exam when the symptoms are nonspecific. The major limitation is the small lesions of the bowel wall which can be disregarded, and to the difficulty of defining the organ of origin in big expansive processes. Ultrasound has a role in the identification of intussusception, noting that primary or secondary wall lesions can be a locus of intussusception. Therefore, in neoplastic disease of the small bowel, ultrasound can be helpful, but not conclusive, and must be supplemented by axial methods.

CT and MRI, with or without enteroclysis, not only provide adequate detail of the wall but also extraparietal, locoregional, and distant metastases, so that it is possible to obtain at one time a correct staging (Di Mizio et al. 2006). MRI has a higher intrinsic contrast resolution than CT, but the long execution times of the examination and the frequently poor cooperation of patients reduce the performance in clinical practice. CT examination is faster and better tolerated (Engin 2008). In the last 10 years, CT has become the method of choice for the study of the small intestine thanks to the possibility of acquiring thin collimation images and with the help of double contrast, oral and venous, as well as the possibility of post-processing reconstruction of the images in coronal and sagittal planes (Maglinte et al. 2007). CT also plays a role in the follow-up of patients during neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and postoperative therapy identifying early complications and relapse or recurrence of local/distant disease (La Seta et al. 2006).

31.4.1 Benign Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions

The most frequent benign tumor in the elderly is the adenoma. Adenomas are epithelial tumors, sessile or pedunculated, small (<3 cm), and usually single, with a predilection for the duodenum and the proximal jejunum. In some syndromes such as familial adenomatous polyposis, they may be multiple and involve the entire digestive tract. The adenomas can be classified as villous (about 40 %), tubular, and tubulo-villous, and they can be sessile or pedunculated. Villous polyps are sessile and lobulated, usually larger than tubular polyps and with a higher probability of malignant transformation, especially if larger than 2 cm. The adenoma of Brunner glands is a hamartomatous lesion that may mimic adenoma; the distinction can be based on the origin; the lesion is on the anterior wall between the first and the second portions of the duodenum.

Ultrasound is able to identify indirect signs, such as the enteroenteric intussusception. Barium studies can show intraluminal defects, sessile or pedunculated; the origin from the mucosa is identified by the alteration of the duodenal fold. At CT the lesion appears as bowel wall thickening or as polypoid formation with homogeneous contrast enhancement after IV administration, similar to that of the contiguous loop wall (Fig. 31.7a–c). On MRI, the adenomas appear as wall thickening or polypoid lesions with signal similar to the wall in T1- and T2-weighted sequences. After administration of gadolinium, the contrast enhancement is similar to that of mucosa (Appleyard et al. 2000).

Fig. 31.7

(a–c) Duodenal large polyp. Oral contrast CT, MPR coronal reconstruction: intraluminal polypoid mass of the second portion of the duodenum with a short stalk and homogeneous enhancement (a, b). 3D reconstruction viewed from inside (c)

The leiomyomas are the most frequent benign tumors of the small intestine in the young adult. A missed diagnosis in early age, due to the absence of symptoms, often explains identification in old age. The leiomyomas originate from smooth muscle, usually from the muscularis propria, especially in the jejunum. The solid lesion, well circumscribed, lacks a capsule and grows slowly, with submucosal (endoenteric) and/or subserosal (exoenteric) manifestations. The symptomatology is related to the size and the vascularization; an impairment of the latter may cause bleeding for ulceration of the mucosal surface. The leiomyomas are responsible for about 50 % of cases of small bowel bleeding.

Ultrasonography can identify a leiomyoma as a wall thickening: mass limited to II–III layers, with attenuation of soft tissue that can distort the mucosal and/or serosal profile. At barium studies it is easier to identify endoenteric leiomyomas, as intraluminal defects with smooth surface, for the distension of the normal mucosa, without folds interruption (Fig. 31.8). The exoenteric lesion can be diagnosed only if it is large and leads to “separation” of the loops. CT scanning identifies a spherical or oval lesion of the submucosa, with the typical attenuation of soft tissue, usually homogeneous, although calcifications may be present, and after administration of intravenous contrast medium has an intense and homogeneous enhancement due to the rich vascularization. On MRI the lesion appears as a parietal mass with T1- and T2-weighted signal similar to the muscle tissue, microcalcifications are not recognized, and gadolinium shows homogeneous and intense enhancement.

Fig. 31.8

Duodenal leiomyoma. Double-contrast barium study: intraluminal contour mass defect with well-defined margins arising from the wall of the second portion of duodenum. Note the typical features of submucosal masses with the margins forming obtuse angles with the duodenal wall and intact mucosa surface

The homogeneity of the lesion is indicative of benignity, but a differential diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma should be considered both because of the age of the patient and because the large lesions tend to degenerate into a malignancy (Anzidei et al. 2011).

The leiomyomas also have to be differentiated by neurogenic tumors, lesions originating from the submucosal and myoenteric plexus. Radiological features often do not allow a differential diagnosis, whereas the clinical history can help because they are often neurofibromas, which affect several organs in systemic neurofibromatosis.

Lipomas are common benign neoplasms in the elderly, with a peak incidence between the sixth and seventh decades. Jejunum and ileum, particularly in the terminal tract, are frequently the sites of origin. The lesion consists of a submucosal well-circumscribed proliferation of fat, with an endoenteric growth vector; proliferation towards the outside is inhibited by the muscularis propria.

Lipomas appear as single lesions of various size; when the lesion is smaller than 1 cm, it is usually asymptomatic, with an incidental diagnosis, whereas larger lesions have a nonspecific accompanying symptoms, characterized by abdominal pain, palpable mass, and intestinal bleeding. Lesions greater than 4 cm in size are responsible for subocclusion due to enteroenteric intussusception (for submucosal and subserosal lipomas) or to volvulus (subserosal neoformation can cause intestinal constriction and volvulus).

Ultrasound can identify large lipomas as hyper- or hypoechoic wall masses or identify the “pseudokidney” sign. Studies with double-contrast barium may be helpful in the diagnosis; the cancer commonly presents as an intraluminal defect, oval or round, with the characteristic “squeeze sign” related to the change of the shape of the lesion as a result of peristalsis or manual pressure. The peristalsis is preserved and the bowel mucosa is without alteration. The limitations of barium studies are the size of the tumor and the difficult differential diagnosis with other submucosal lesions; moreover they do not have to be performed in case of acute abdomen. The abdominal CT examination is considered the gold standard for diagnosis. Lipomas appear as submucosal and homogeneous lesions, with attenuation values of adipose tissue (−130/−60 UH), without enhancement after intravenous contrast medium administration. The differential diagnosis must be made with mesenteric fat intussusception. On MRI, lipomas have T1- and T2-weighted signal of soft tissue, with reduction of the signal in fat-saturated sequences (Fang et al. 2010). Hamartomatous lesions are incidentally found in the elderly, being more frequent in the young. Patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome have a high risk of gastrointestinal tumors.

31.4.2 Primary Malignant Diseases

Adenocarcinoma of the small intestine is about 50 times less common than in the colon. In 50 % of cases the most common site of origin is the duodenum, especially in the periampullar tract; in the remaining cases, the jejunum is more often affected than the ileum (Hong et al. 2009). Several factors can explain the low incidence of small intestine adenocarcinoma in young people: large amounts of intraluminal alkaline liquids, the rapid transit of intestinal contents, a high concentration of immunoglobulin A, and the low bacterial load, all of which tend to alter with age and, therefore, can explain the higher incidence of cancer after 60 years. Risk factors include Crohn disease, celiac disease, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Lynch syndrome, and the presence of ileostomy or biliojejunal anastomosis.

Symptoms are nonspecific: abdominal pain, subocclusive crisis, weight loss, iron-deficiency anemia, melena, and jaundice (Kala et al. 2008

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree