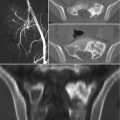

Fig. 8.1

A comprehensive algorithm for the management of GCT of the sacrum

Table 8.1

Summary of the most important published studies on the treatment of GCT of the sacrum

Study | Patients (n) | Treatment | Follow-up (months) | Survival to local recurrence (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

McDonald et al. 1986 [53] | 14 | Intralesional surgery | Mean, 84; range, 48–312 | 77% at 84 months |

Turcotte et al. 1993 [54] | 26 | Intralesional surgery, radiation therapy | Mean, 94; range, 84–396 | 67% at 84 months |

Marcove et al. 1994 [55] | 7 | Cryosurgery and intralesional surgery and/or limited excision | Median, 147; range, 24–170 | 71.4% at 147 months |

Lin et al. 2002 [35] | 18 | Selective arterial embolization, intra-arterial cisplatin | Median, 105; range, 6–205 | 69% at 120 months, 57% at 180 and 240 months; no significant effect of cisplatin |

Lackman et al. 2002 [34] | 5 | Serial selective arterial embolization | Mean, 90; range, 48–204 | 80% at 80.4 months |

Leggon et al. 2004 [6] | 10 | Radiation therapy, intralesional surgery, and chemotherapy | Mean, 96; range, 11–254 | 80% at 36 months |

Hosalkar et al. 2007 [33] | 9 | Serial selective arterial embolization | Mean, 107; median, 94; range, 46–254 | 78% at 108 months |

Guo et al. 2009 [15] | 24 | Intralesional surgery, intraoperative occlusion of the abdominal aorta | Mean, 58; median, 50; range, 25–132 | 69.6% at 60 months |

Ruggieri et al. 2010 [4] | 31 | Intralesional surgery with and without postoperative radiation therapy, selective arterial embolization, phenol, and liquid nitrogen | Mean, 118; median, 108; range, 36–276 | 90% at 60 and 120 months |

Thangaraj et al. 2010 [16] | 9 | Curettage alone or with embolization ± spinal stabilization ± radiotherapy | Mean, 124; range, 24–256 | 33% at 19 months |

Gaztañaga et al. 2011 [56] | 4 | Intralesional surgery and radiotherapy | Median, 132; range, 32–144 | 0% at 32 months |

Balke et al. 2011 [45] | 10 | Curettage and PMMA | Median, 52; range, 15–133 | 20% at 12 months |

Li et al. 2012 [57] | 32 | Resection (25), curettage (7) | Median, 42; range, 18–115 | 37.5% at 42 months |

Chen et al. 2014 [5] | 4 | Intralesional curettage and zoledronic acid-loaded cement balls | Mean, 28; range, 25–33 | 0% at 25 months |

Heijden et al. 2014 [18] | 26 | Intralesional excision with either local adjuvants, radiotherapy, IFN-α, or bisphosphonates | Median, 98; range, 6–229 | 54% at 13 months |

Surgical management of GCT of the sacrum is more complicated, mostly as a result of late discovery, large size, spinal or pelvic instability, and frequent involvement of nerve roots [15–17]. In case of extended involvement of the proximal part of the sacrum, total sacrectomy has been advocated, as it has been associated with low local recurrence rates (0–8%) [18]. However, as there is a high risk of infection (18–46%), neurological deficits (24–38%), and bladder, rectal, or sexual dysfunction (18–47%), it could be considered overtreatment for an essentially benign tumor [64, 71]. Partial sacrectomy is less mutilating and can be performed for sacral involvement distal to the S2 segment, allowing for preservation of bowel and bladder function without the need for lumbopelvic reconstruction [4]. Marginal resection can be performed for lesions distal to the S3 segment.

Curettage is less invasive, permitting salvage of nerve roots and visceral structures and maintenance of intrinsic spinal or pelvic support. However, curettage results in relatively high recurrence rates, ranging from 10 to 37% [25]. Caution is warranted with the application of local adjuvants such as phenol or liquid nitrogen in the vicinity of neurovascular structures, as they can induce local necrosis and transient nerve damage [18]. After curettage, spinal or pelvic stability should be assessed and stabilization performed if needed. If at least S1 is preserved after intralesional resection, reconstruction is generally unnecessary. If S1 is partially or completely resected, stabilization with iliolumbar screw fixation is preferred [25].

Selective arterial embolization can be performed serially as primary treatment, or a precursor to surgery to reduce bleeding, as these tumors can be associated with occasional catastrophic intraoperative hemorrhage [16, 33–35]. Systemic therapy alternatives for GCT include bisphosphonates, IFN-a, and denosumab. Denosumab is a human monoclonal antibody and RANKL inhibitor that blocks osteoclast maturation and thus its osteolytic properties. It is currently approved for osteoporosis treatment in postmenopausal women at risk for fracturing, to increase bone mass in patients with prostate or breast cancer who are at risk for fracture due to androgen deprivation therapy or aromatase inhibitor therapy, respectively, and for the prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastases from solid tumors. It has also been approved by the FDA for the treatment of adults and skeletally mature adolescents with GCTB that is unresectable, or when surgical resection is likely to result in severe morbidity [72]. A recent study has shown clear clinical benefits of denosumab therapy [73]. Finally, another GCT treatment modality is represented by radiotherapy. More used in the near past, it has now gone in misuse, due to concerns for radiation-induced sarcoma. The reported risk of malignant transformation varies between 0 and 5% [74, 75]. Nowadays, radiotherapy should be restricted to those rare cases of unresectable, residual, or recurrent GCTB in which treatment with RANKL inhibitors is not possible or has been proven to be ineffective and when surgery would lead to unacceptable morbidity.

Conclusion

GCT of the sacrum is a benign, but locally aggressive and rarely metastasizing tumor. Aggressive surgery is usually associated with unacceptable morbidity. Treatment decisions should be made by a multidisciplinary team composed of experts in the field of musculoskeletal oncology. Definitive diagnosis should be obtained by accurate imaging, including high-quality radiographs and at least MR imaging. A CT-guided biopsy should complete staging and preoperative planning, for histopathological confirmation of diagnosis. Preoperative selective arterial embolization should be considered in all patients. Preferred treatment is intralesional curettage with local adjuvants. If curettage is not feasible, due to soft tissue extension or neurovascular compromise, neoadjuvant systemic targeted therapy with denosumab should be considered, as it may downsize the lesion and create a calcified rim around the tumor, making excision possible. If curettage is still impossible, en bloc resection may be considered. After surgery, spinopelvic stability should be assessed and reconstruction performed if necessary. Radiotherapy should be restricted to multiple recurrent of refractory GCT, and when denosumab is unavailable, contraindicated or ineffective.

Conflict-of-Interest Statement

No benefits have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject matter of this article.

References

1.

Dorfman HD, Czerniak B. Bone tumors. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998.

3.

4.

Ruggieri P, Mavrogenis AF, Ussia G, Angelini A, Papagelopoulos PJ, Mercuri M. Recurrence after and complications associated with adjuvant treatments for sacral giant cell tumor. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(11):2954–61. doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1448-8.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

5.

Chen KH, Wu PK, Chen CF, Chen WM. Zoledronic acid-loaded bone cement as a local adjuvant therapy for giant cell tumor of the sacrum after intralesional curettage. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(10):2182–8. doi:10.1007/s00586-015-3978-y.CrossRefPubMed

6.

Leggon RE, Zlotecki R, Reith J, Scarborough MT. Giant cell tumor of the pelvis and sacrum: 17 cases and analysis of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;423:196–207.CrossRef

7.

Turcotte RE. Giant cell tumor of bone. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37(1):35–51. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2005.08.005.CrossRefPubMed

8.

Zhang K, Chen K, Zhou M, Chen H, Lu J, Yang H. Extremely large giant-cell tumor of sacrum with successful resection via posterior approach. Spine J. 2015;15(7):1684–5. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2015.02.007.CrossRefPubMed

9.

Feigenberg SJ, Marcus Jr RB, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT, Berrey BH, Enneking WF. Radiation therapy for giant cell tumors of bone. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;411:207–16. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000069890.31220.b4.CrossRef

10.

Reid R, Banerjee S, Sciot R. Giant cell tumour. In: Fletcher D, Unni K, Mertens F, editors. WHO Classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics: tumors of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. p. 310–2.

11.

Kransdorf M, Murphey M. Giant cell tumor. In: Davies M, Sundaram M, James S, editors. Imaging of bone tumors and tumor-like lesions. Berlin: Springer; 2009. p. 321–36.CrossRef

12.

Dahlin DC, Cupps RE, Johnson Jr EW. Giant-cell tumor: a study of 195 cases. Cancer. 1970;25(5):1061–70.PubMed

13.

Resnick D. Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995.

14.

Unni KK, Dahlin DC. Dahlin’s bone tumors: general aspects and data on 11,087 cases. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996.

15.

Guo W, Ji T, Tang X, Yang Y. Outcome of conservative surgery for giant cell tumor of the sacrum. Spine. 2009;34(10):1025–31. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819d4127.CrossRefPubMed

16.

Thangaraj R, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, Stirling AJ, Spilsbury J, Spooner D. Giant cell tumour of the sacrum: a suggested algorithm for treatment. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(7):1189–94. doi:10.1007/s00586-009-1270-8.CrossRefPubMedPubMedCentral

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree