, Joungho Han2, Man Pyo Chung3 and Yeon Joo Jeong4

(1)

Department of Radiology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(2)

Department of Pathology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(3)

Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(4)

Department of Radiology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

Abstract

Ground-glass opacity (GGO) is caused by partial displacement of air in lung parenchyma. The opacity is caused by partial filling of airspaces, interstitial thickening (due to fluid, cells, or fibrosis) (Figs. 21.1 and 21.2), partial collapse of alveoli, and increased capillary blood volume. Without reticulation, the GGO areas usually represent active inflammatory or reversible disease state.

Ground-Glass Opacity without Reticulation, Subpleural and Patchy Distribution

Definition

Ground-glass opacity (GGO) is caused by partial displacement of air in lung parenchyma. The opacity is caused by partial filling of airspaces, interstitial thickening (due to fluid, cells, or fibrosis) (Figs. 21.1 and 21.2), partial collapse of alveoli, and increased capillary blood volume. Without reticulation, the GGO areas usually represent active inflammatory or reversible disease state.

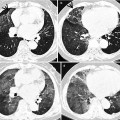

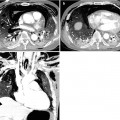

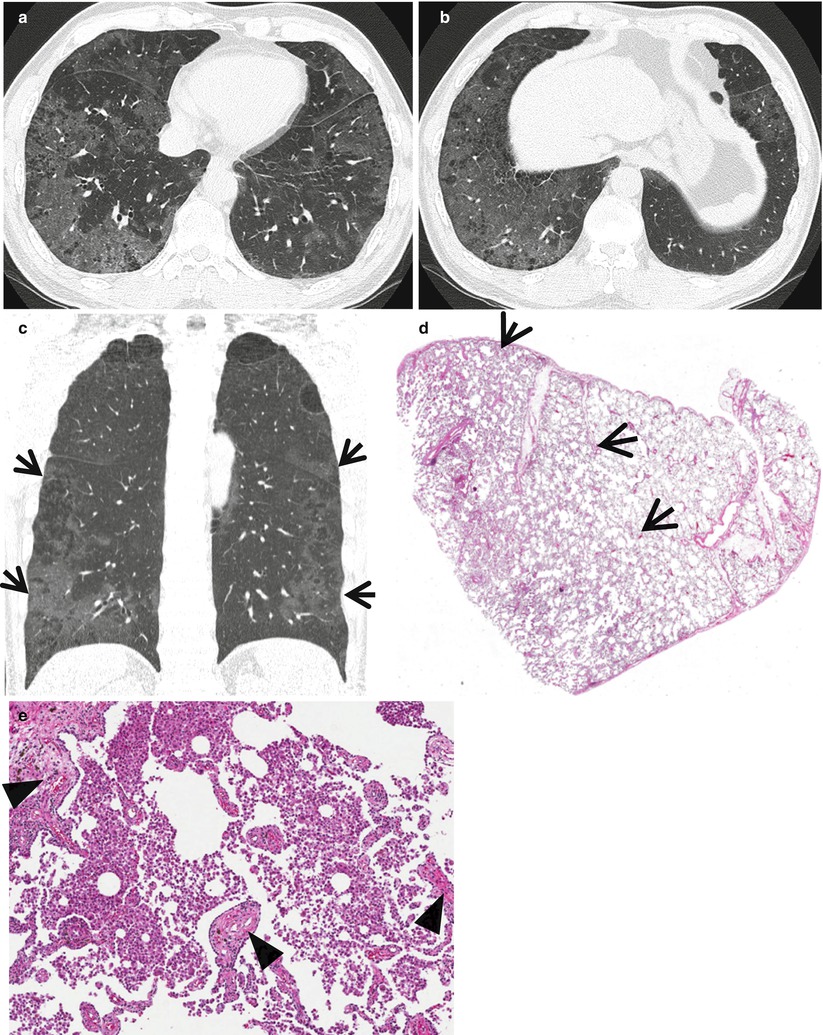

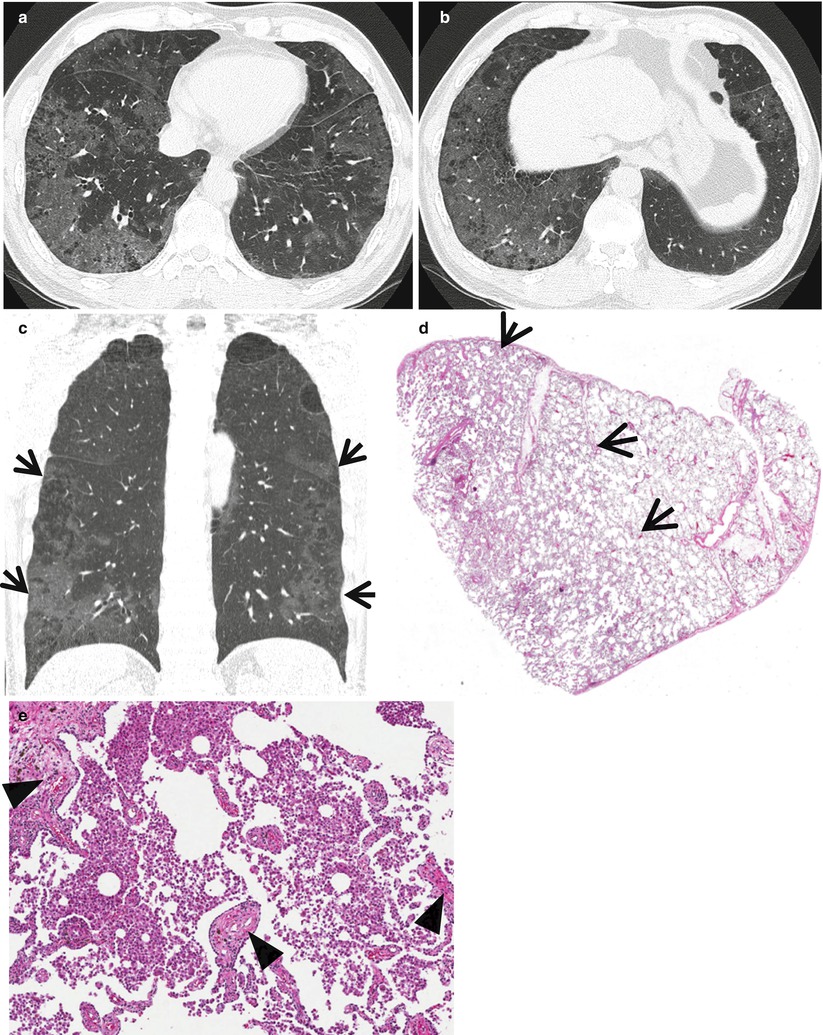

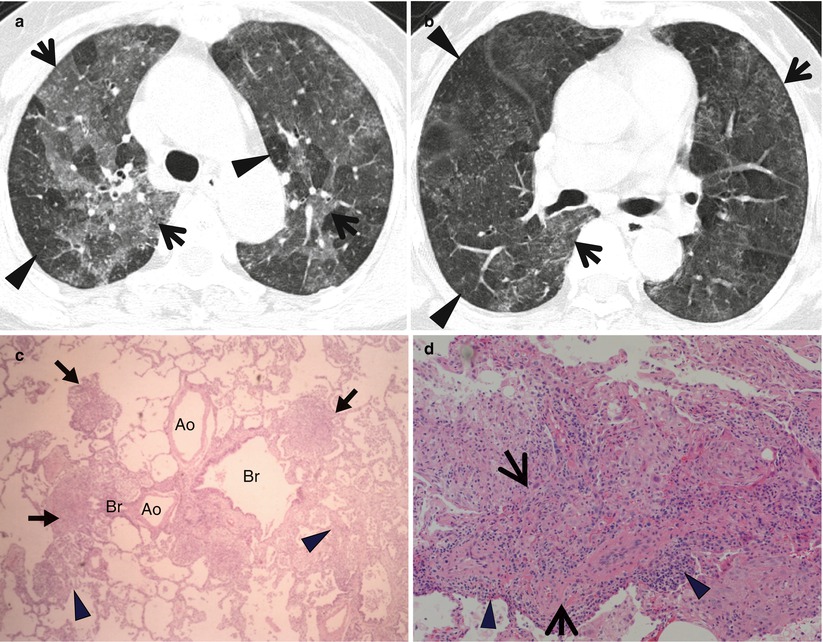

Fig. 21.1

Cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonia manifesting as diffuse ground-glass opacity without reticulation in a 10-year-old girl. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of right upper lobar bronchus (a) and inferior pulmonary veins (b), respectively, show diffuse ground-glass opacity in both lungs. (c) Low-magnification (×40) photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy specimen obtained from right lower lobe demonstrates diffuse alveolar wall thickening with inflammatory cell infiltration. Lesions are temporally homogeneous and uniform in alveolar wall thickening. Areas of focal organizing pneumonia (arrows) are associated. (d) High-magnification (×200) photomicrograph discloses alveolar wall thickening with chronic inflammatory cell infiltration and mild alveolar pneumocytes hyperplasia and many intra-alveolar macrophage aggregation. (e, f) Two-year follow-up CT scans obtained at similar levels to a and b, respectively, exhibit complete disappearance of ground-glass opacity in both lungs. Patient received corticosteroid therapy

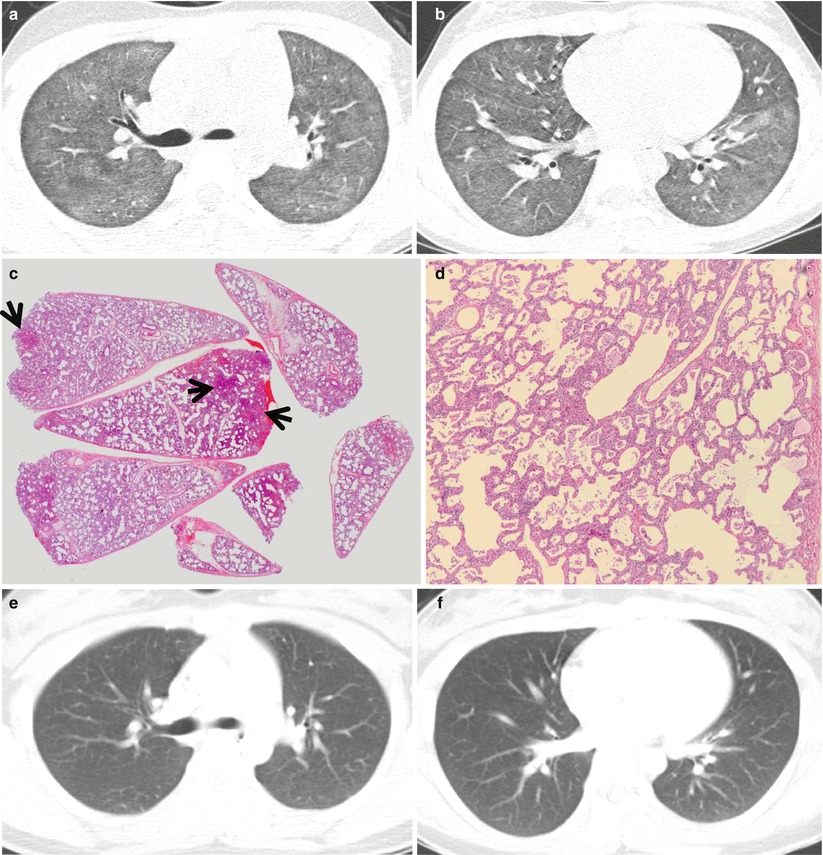

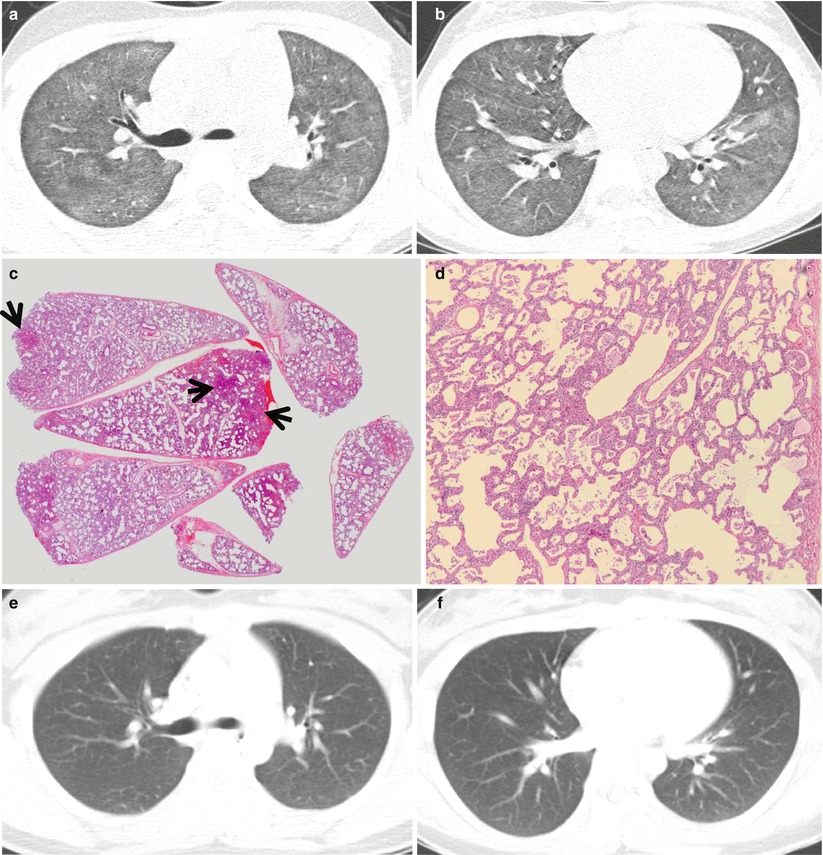

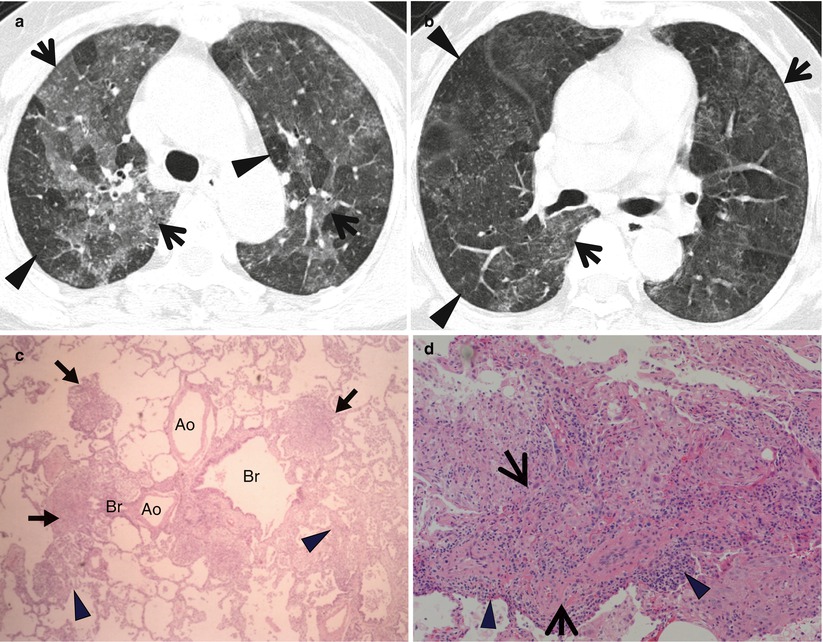

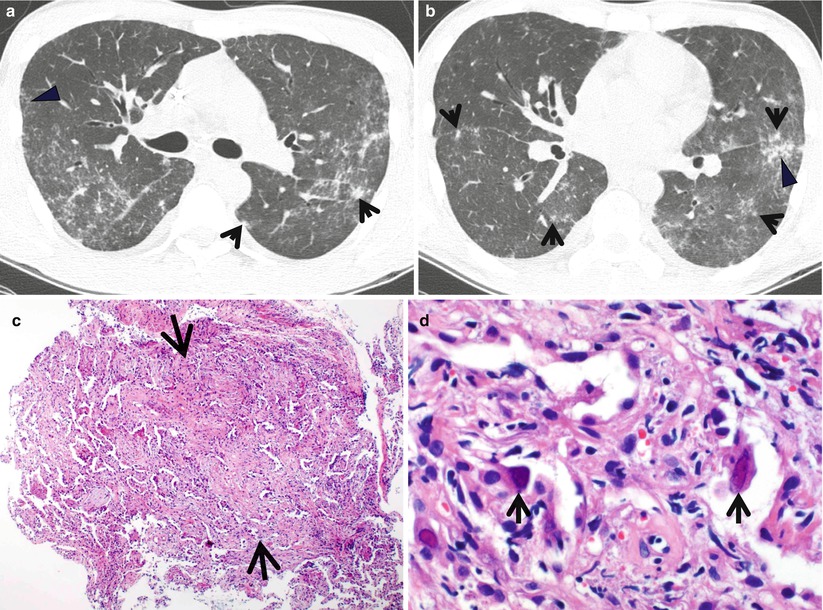

Fig. 21.2

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia presenting as patchy areas of ground-glass opacity without reticulation in a 51-year-old smoker man. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans (1.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of suprahepatic inferior vena cava (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show patchy and extensive but subpleural areas of ground-glass opacity in both lungs. (c) Coronal reformatted CT image (2.0-mm section thickness) demonstrates subpleural patchy areas of ground-glass opacity (arrows) in both lungs. Also note bullae in upper lung zones. (d) Low-magnification (×40) photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy specimen obtained from right lower lobe exhibits areas of uniform accumulation of inflammatory cells in intra-alveolar spaces and mildly in interstitium (alveolar walls) (arrows). (e) High-magnification (×200) photomicrograph discloses intra-alveolar macrophage accumulation and mild interstitial fibrosis (arrowheads)

Diseases Causing the Pattern

Distribution

The distribution of GGO lesions in cellular NSIP is subpleural, usually without obvious upper–lower lung zone gradient (this gradient, overt in usual interstitial pneumonia with lower lung zone predominance) [1]. In DIP, the opacity had subpleural and lower lung zone predominance [1]. In two-thirds of patients, the opacity lesions in COP are distributed along the bronchovascular bundles or subpleural lungs [2]. In chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, CT shows subpleural opacity with slight upper lung zone predominance [3].

Clinical Considerations

The presence of asthma history suggests the diagnosis of eosinophilic lung disease (approximately 40 % of patients with chronic eosinophilic lung disease have asthma) [3]. In drug-induced lung disease and lung involvements of collagen vascular diseases, lung abnormalities can be assessed with pattern approach, namely NSIP, DIP, COP, and eosinophilic lung disease-like patterns [4, 5].

Key Points for Differential Diagnosis

Diseases | Distribution | Clinical presentations | Others | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zones | ||||||||||||

U | M | L | SP | C | R | BV | R | Acute | Subacute | Chronic | ||

Cellular NSIP | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

DIP | + | + | + | + | + | + | Smokers’ lung disease | |||||

COP | + | + | + | + | + | + | Consolidation predominant | |||||

CEP | + | + | + | + | + | + | Consolidation predominant; asthma in 40 % of patients | |||||

Cellular Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia

Pathology and Pathogenesis

The inflammatory process in cellular NSIP is diffuse and uniform, mainly involving the alveolar walls and variably affecting the bronchovascular sheaths and pleura (Fig. 21.1). When air space organization (the organizing pneumonia pattern) is present, it is not uniformly distributed as might occur in organizing infectious pneumonia. When fibrosis occurs in NSIP, it is usually mild and preserves lung structure. Peribronchiolar metaplasia of variable extent may be seen, but microscopic honeycombing (HC) is characteristically absent [6].

Symptoms and Signs

The typical clinical presentation of NSIP is breathlessness and cough of approximately 6–7 months’ duration, predominantly in women, in never-smokers, and in the sixth decade of life [7]. Chest examination reveals bilateral inspiratory crackles in most patients. Digital clubbing is rarely seen in cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Systemic symptoms, including fever and arthralgia, are frequently observed.

CT Findings

Cellular NSIP is often characterized by the absence of severe fibrotic changes or HC. The most common CT findings of NSIP are GGO (Fig. 21.1) and fine reticular abnormality [8]. Traction bronchiectasis may be present or absent. All these findings have a symmetric lower lung zone distribution. Consolidation sometimes is seen, but is not the primary abnormality of NSIP. If rapidly developing airspace consolidation or GGO is seen in a patient with NSIP, one should consider the possibility of an acute exacerbation or infection [9]. Although cellular NSIP is characterized by the absence of severe fibrotic changes, imaging features of cellular and fibrotic NSIP often overlap and there is no reliable way to differentiate between cellular and fibrotic NSIP [10].

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Cellular NSIP demonstrates prominent inflammation without significant fibrosis. Areas of GGO correspond histologically to the areas of interstitial thickening by inflammatory cells and fibrous tissue (Fig. 21.1), whereas the areas of consolidation are related to areas of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia [11].

Patient Prognosis

Prognosis of cellular NSIP is excellent, with a 10-year survival up to 100 %. Corticosteroids are the main drugs for the treatment.

Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia

Pathology and Pathogenesis

On scanning magnification, the DIP has an eosinophilic appearance due to the presence of eosinophilic macrophages uniformly filling air spaces (Fig. 21.2). Mild interstitial thickening by fibrous tissue is the rule and is uniform in appearance. When chronic inflammation is evident at scanning magnification, it is centrilobular and associated with respiratory bronchioles [12].

Symptoms and Signs

The clinical presentation of patients with DIP is nonspecific. It consists of chronic cough and dyspnea [13]. Physical examination reveals inspiratory crackles in approximately 60 % and digital clubbing in 25–50 % of patients.

CT Findings

CT–Pathology Comparisons

Patient Prognosis

Smoking cessation is the first and most important therapeutic intervention for individuals with DIP who smoke. Pharmacologic therapy with corticosteroids is often used in patients with marked symptoms or significant impairment of lung function. Spontaneous remission has also been described. DIP can gradually progress, particularly in those who continue to smoke.

Ground-Glass Opacity without Reticulation, with Small Nodules

Definition

Ground-glass opacity (GGO) is caused by partial displacement of air in lung parenchyma. The opacity is caused by partial filling of airspaces, interstitial thickening (due to fluid, cells, or fibrosis), partial collapse of alveoli, or increased capillary blood volume. Without reticulation, the GGO areas usually represent active inflammatory or reversible disease state (repetition see section “Ground-Glass Opacity without Reticulation, Subpleural and Patchy Distribution”). In several diseases, the diffuse areas of GGO may contain small identifiable poorly defined (GGO) nodules within the lesions or be associated with the nodules (Figs. 21.3, 21.4, and 21.5).

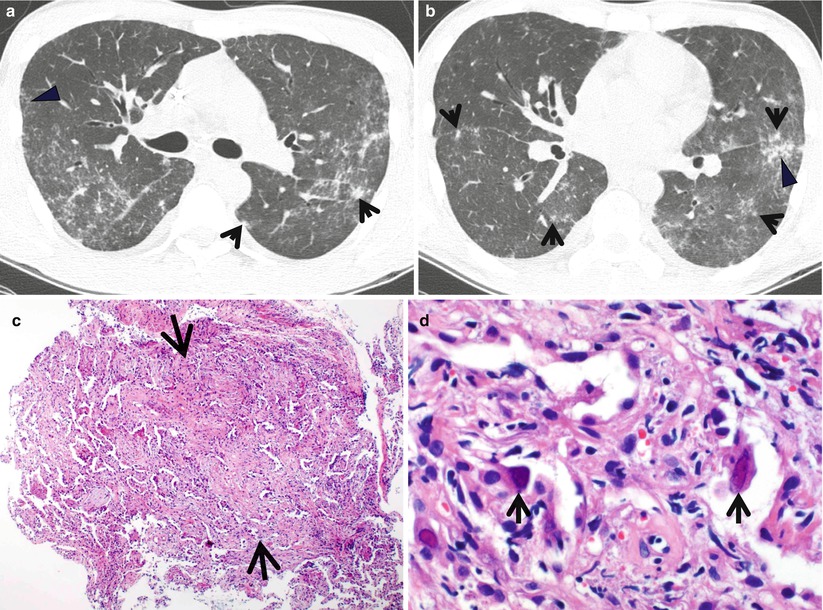

Fig. 21.3

Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis in a 66-year-old woman. (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section (1.0-mm section thickness) CT scans obtained at levels of azygos arch (a) and distal bronchus intermedius (b), respectively, show the so-called head cheese sign with mixed infiltrative (ground-glass opacity, arrows) and obstructive (mosaic attenuation, arrowheads) abnormalities. Ground-glass opacity is caused by lung infiltration, whereas mosaic perfusion with decreased vessel sign is usually caused by small airway disease. (c) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph of surgical biopsy specimen obtained from right upper lobe demonstrates bronchiolocentric granulomas (arrows) along with lymphocyte infiltration (arrowheads) in peribronchiolar interstitium (alveolar walls). Ao arteriole, Br bronchiole. (d) High-magnification photomicrograph (×200) discloses loosely formed granuloma (arrows) comprising epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells and surrounding lymphocyte cuff (arrowheads)

Fig. 21.4

Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in a 28-year-old man with acute myeloid leukemia. (a, b) Lung window images of thin-section (1.0-mm section thickness) CT scans obtained at levels of main bronchi (a) and basal trunk (b), respectively, show patchy areas of ground-glass opacity in both lungs associated with branching small nodular structures (tree-in-bud sign, arrowheads) and somewhat larger nodules (arrows) of acinus size. (c) High-magnification (×100) photomicrograph of surgical lung biopsy specimen obtained from left lower lobe demonstrates organizing pneumonia (arrows) pattern with viral inclusion in epithelial cells consistent with cytomegalovirus pneumonia. (d) High-magnification (×200) photomicrograph discloses viral inclusion bodies (arrows) in epithelial cells

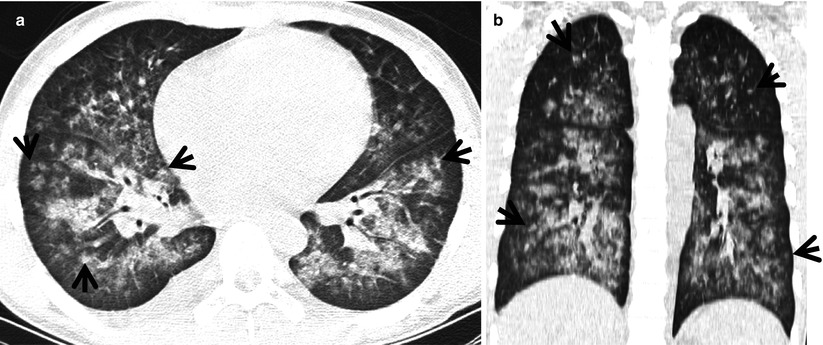

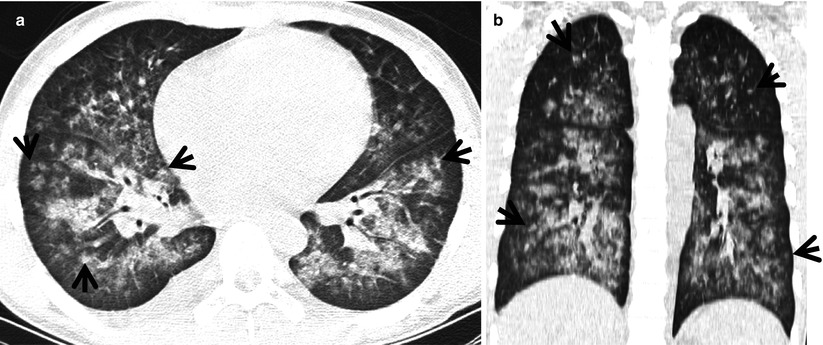

Fig. 21.5

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in a 15-year-old boy with IgA nephropathy and pulmonary capillaritis. (a, b) Lung window image of CT (2.5-mm section thickness) scan obtained at level of inferior pulmonary veins shows patchy and extensive parenchymal opacity in both lungs. Please also note small poorly formed centrilobular nodules (arrows) in both lungs

Diseases Causing the Pattern

Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) (Fig. 21.3), cytomegalovirus pneumonia (CMV pneumonia) (Fig. 21.4), and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) particularly associated with pulmonary vasculitis (Fig. 21.5) may exhibit diffuse or extensive areas of GGO containing small poorly formed nodular (mainly GGO nodules) lesions [16].

Distribution

The areas of GGO in subacute HP are usually extensive, bilateral, and symmetric [17]. In some patients, they are patchy or asymmetric. Also in cytomegalovirus pneumonia, the GGO lesions show diffuse or patchy distribution without zonal predominance [18, 19]. The lesions in DAH are diffuse in the upper and lower lobes in approximately 75 % of patients or are localized in the lower part of the lungs in 25 % of patients. In both the cases, the apices and costophrenic angles are usually spared [20].

Clinical Considerations

Bird fancier’s lung and farmer’s lung are the two most leading cause of hypersensitivity pneumonitis [21]. CMV pneumonia is a common life-threatening complication seen in immunocompromised patients. It occurs most commonly after bone marrow and solid organ transplantation and in patients with AIDS [19]. The clinical syndrome in DAH includes hemoptysis, anemia, diffuse radiologic pulmonary opacity, and hypoxemic respiratory failure. The most common underlying histology of DAH is of a small vessel vasculitis known as pulmonary capillaritis, usually seen with seropositive systemic vasculitis, or a connective tissue disorder (bland pulmonary hemorrhage), and diffuse alveolar damage due to a number of injuries including, drugs, coagulation disorders, and infection [22].

Key Points for Differential Diagnosis

Diseases | Distribution | Clinical presentations | Others | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zones | ||||||||||||

U | M | L | SP | C | R | BV | R | Acute | Subacute | Chronic | ||

Subacute HP | + | + | + | + | + | + | Bird fanciers, farmers | |||||

CMV pneumonia |

||||||||||||