Chapter 21 Head and neck cancer – general principles

Prevention and early diagnosis

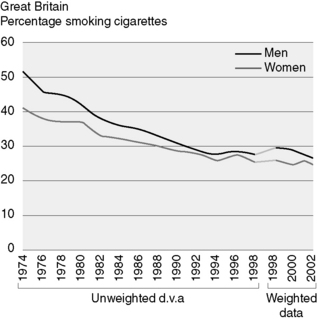

Tobacco cessation is also an important factor in preventing head and neck cancers. The prevalence of cigarette smoking has fallen by over 20% in men over the last 20 years (Figure 21.1). Aggressive treatment of pre-malignant conditions is important in reducing the incidence of invasive cancer.

Dentition

When taking consent from patients for radiotherapy, they must be counselled about the risks of dental problems following the treatment and, in particular, osteoradionecrosis of the mandible which can develop spontaneously but is more likely after dental procedures, particularly extractions (Figure 21.2). Patients need to be encouraged to use fluoride mouthwash or gel daily and to have regular dental check-ups – and if dental work is considered necessary it should be performed by specialist hospital dental teams in view of the high risk of complications.

Indications for radiotherapy

Postoperative radiotherapy

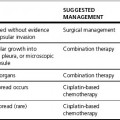

There are a number of indications for postoperative radiotherapy (Table 21.1). In some cases, postoperative radiotherapy is mandatory, in other situations the real benefit to the patient is less clear.

Table 21.1 Indications for postoperative radiotherapy

Positive (involved) resection margins Extracapsular lymph node spread Close resection margins, i.e. <5 mm Invasion of soft tissues ≥2 nodes involved >1 positive nodal group (i.e. level) Involved node >3 cm in diameter Vascular invasion Perineural invasion Poor differentiation Stage III/IV Multicentric primary Oral cavity/oropharynx tumours with involved nodes at level IV/V Carcinoma in situ/dysplasia at resection margin/‘field changes’ |

Guidelines for cervical nodal irradiation in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck.

Reproduced with kind permission of Dr M. Henk and the CHART steering committee

Target volumes

Definitive radiotherapy

When radiotherapy (with or without chemotherapy) is the definitive treatment, a gross tumour volume (GTV) is present and a planning CT scan will allow it to be delineated combined with information from the examination under anaesthesia (EUA), histology and other diagnostic imaging. Help from a specialist radiologist is recommended. The CTV is to account for microscopic spread. Overtly involved nodes should be included in that CTV. Occult lymph node metastases occur in up to 20–30% of the N0 neck patients, so prophylactic irradiation is required for many head and neck tumours and is delineated as a separate CTV. The sites where this is not considered are early glottic or subglottic cancers (T1/T2 disease) (Table 21.2). The likelihood of nodal involvement has been widely studied and it is clear that the probability increases with site of primary, size of primary and differentiation.

Table 21.2 Indications for nodal irradiation by tumour site

| Indications | Irradiation |

|---|---|

| Oral cavity | |

| T2N0 with well-lateralized primary | Levels I and II on the same side |

| T2N1 with well-lateralized primary | Levels I to V on the same side |

| T2N0 with primary approaching midline, all T3N0 and T4N0 | Levels I, II and III bilaterally |

| All others | Levels I to V bilaterally |

| Oropharynx | |

|---|---|

| T2N0 tonsil | Levels I and II on the same side |

| T2N1 tonsil | Levels I to V on the same side |

| T2N0 other sites | Levels I, II and III bilaterally |

| All others | Levels I to V bilaterally |

| Nasopharynx | |

|---|---|

| Squamous cell carcinoma T1 – T4 N0 |