Hepatitis B viral infection

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection

Hereditary hemochromatosis

Chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis

Aflatoxin

Contaminated drinking water

Betel nut chewing

Tobacco and alcohol abuse

Diabetes mellitus

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Obesity

Iron overload

Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency

Acute intermittent porphyria

Gallstones and cholecystectomy

Dietary factors—consumption of red meat and saturated fat

1.2.2 Clinical Presentation

Patients with HCC usually present in advanced stages of the disease because of the absence of pathognomonic symptoms [5, 6]. The median survival following diagnosis is approximately 6–20 months [7].

Patients are largely asymptomatic, apart from symptoms of existing chronic liver disease. A diagnosis of HCC should be suspected in situations of recent onset hepatic decompensation in a patient with compensated chronic liver disease. Table 1.2 lists the common presenting symptoms and signs. Tumor rupture with intraperitoneal bleed is a rare clinical presentation which requires urgent resuscitation, angioembolization, or even surgery.

Table 1.2

Hepatocellular carcinoma— clinical presentation

Symptoms |

– Asymptomatic—incidental finding |

– Jaundice, anorexia, weight loss, malaise |

– Vague upper abdominal pain |

– Upper abdominal mass |

– Acute presentation—intralesional bleed with acute onset severe abdominal pain, intraperitoneal rupture with bleed |

Signs |

– Hepatomegaly (50–90%) |

– Hepatic bruit (6–25%) |

– Ascites (30–60%) |

– Splenomegaly due to associated portal hypertension from underlying liver disease |

– Fever (10–50%)—probably due to tumor necrosis |

– Signs of chronic liver disease—jaundice, dilated abdominal veins, palmar erythema, gynecomastia, testicular atrophy, and peripheral edema |

– Budd-Chiari syndrome due to invasion into the hepatic veins causes tense ascites and large tender liver |

– Troisier’s sign—left supraclavicular lymph node enlargement (Virchow’s node) |

HCC can occasionally be associated with paraneoplastic syndromes like hypoglycemia, erythrocytosis, hypercalcemia, or severe watery diarrhea.

1.2.3 Diagnosis and Staging

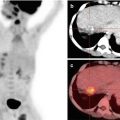

Triple-phase contrast-enhanced CT scan or MRI is the investigative modality of choice for HCC. A diagnosis of HCC can be made for a solid liver lesion with characteristic enhancement patterns, i.e., enhancement in the arterial phase and contrast washout in the venous phase. Both arterial enhancement and venous washout are essential to make a diagnosis of HCC.

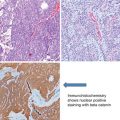

As the majority of patients with HCC have pre-existing chronic liver disease, enrolling these patients into a surveillance program of 6-monthly ultrasound aids in early diagnosis. Fig. 1.1 shows the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) algorithm for suspected HCC [8]. Differentiation between high-grade dysplastic nodules and HCC on biopsy may be challenging and requires evaluation by expert pathologists supplemented with staining for glypican 3, heat shock protein 70, and glutamine synthetase. If the biopsy is negative for HCC, patients should be followed by imaging at 3- to 6-month intervals until the nodule either disappears, enlarges, or displays diagnostic characteristics of HCC.

Fig. 1.1

AASLD algorithm for suspected hepatocellular carcinoma [8]. CT computed tomography, MDCT multidetector CT, MRI, magnetic resonance imaging, US ultrasonography

Serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels are not included in the diagnostic algorithm for HCC as elevated serum AFP may also be seen in patients with chronic liver disease without HCC such as acute or chronic viral hepatitis [9]. However, it is accepted that serum AFP levels greater than 500 μg/L, in a high-risk patient, are diagnostic of HCC [10]. Serum AFP has also emerged as an important prognostic marker in patients being evaluated for liver transplant. An AFP level >1000 μg/L is associated with a high risk for disease recurrence following transplant [11].

The most common sites of extrahepatic metastases in HCC are the lungs, abdominal lymph nodes, and bones, in that order. A CT chest is recommended for all patients being considered for curative resection. On account of low diagnostic yield a bone scan is only recommended for symptomatic patients.

Table 1.3 shows the TNM staging for HCC [12].

Primary tumor (T) | |||

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | ||

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | ||

T1 | Solitary tumor without vascular invasion | ||

T2 | Solitary tumor with vascular invasion or multiple tumors not more than 5 cm | ||

T3a | Multiple tumors more than 5 cm | ||

T3b | Single tumor or multiple tumors of any size involving a major branch of the portal vein or hepatic vein | ||

T4 | Tumor(s) with direct invasion of adjacent organs other than the gallbladder or with perforation of visceral peritoneum | ||

Regional lymph nodes (N) | |||

NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | ||

N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | ||

N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis | ||

Distant metastasis (M) | |||

M0 | No distant metastasis | ||

M1 | Distant metastasis | ||

Anatomic stage/prognostic groups | |||

Stage I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

Stage II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIA | T3a | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIB | T3b | N0 | M0 |

Stage IIIC | T4 | N0 | M0 |

Stage IVA | Any T | N1 | M0 |

Stage IVB | Any T | Any N | M1 |

1.3 Carcinoma of the Gall Bladder and Bile Ducts

1.3.1 Epidemiology and Etiology

The incidence of gall bladder cancer shows a wide degree of geographical variation with the highest incidence recorded in parts of South America, India, Pakistan, Japan, and Korea [13]. The majority of patients with carcinoma of the gall bladder have gall stone disease. However, the incidence of gall bladder cancer in patients with gall stone disease is just 0.5–3% [14]. Table 1.4 lists the risk factors for gall bladder cancer.

Table 1.4

Gall bladder cancer—risk factors

Gallstone disease |

Porcelain gallbladder |

Gallbladder polyps |

Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

Chronic infection—salmonella, Helicobacter |

Congenital biliary cysts—choledochal cysts |

Abnormal pancreaticobiliary duct junction |

Medications—methyldopa, oral contraceptives, isoniazid |

Carcinogen exposure—oil, paper, chemical, shoe, textile industries |

Obesity and elevated blood sugar |

Cholangiocarcinoma arises from the bile duct epithelium and has been classified as intra- and extrahepatic based on anatomical location. Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas are further classified as perihilar (up to the insertion of the cystic duct into the bile duct) and distal. Perihilar tumors in turn are further classified as per the Bismuth-Corlette system into four types (Table 1.5) [15]. Hilar cholangiocarcinomas are collectively known as Klatskin tumors.

Type 1—Tumors below the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts |

Type 2—Tumors reaching the confluence |

Type 3—Tumors involving the confluence and either the right (3a) or left (3b) hepatic ducts |

Type 4—Multicentric tumors or those involving the confluence and both the right and left ducts |

Primary sclerosing cholangitis and fibropolycystic liver disease (e.g., choledochal cysts) are the major risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is also associated with chronic liver disease and liver fluke infestation (e.g., clonorchis sinensis). Two familial syndromes, viz., Lynch syndrome and biliary papillomatosis [16], also predispose to cholangiocarcinoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree