Hip Disorders

Ramesh S. Iyer, MD

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Identify developmental dysplasia of the hip on ultrasound and radiography.

2. Draw the following landmarks on an AP pelvis radiograph: Hilgenreiner line, Perkin line, Shenton line, and acetabular angle.

3. Recognize early and late radiographic findings of Legg-Calves-Perthes disease.

4. Identify slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) on radiography.

5. Identify hip effusion on radiography and ultrasound.

6. List at least two differentiating magnetic resonance (MR) features of septic arthritis from transient synovitis.

INTRODUCTION

The pediatric hip is home to a number of unique pathologies. Evaluating for developmental dysplasia is the most common reason for imaging the hip in neonates. The most likely cause of hip pain in a child often depends on the patient’s age. For example, a 6-year-old boy is more likely to have Legg-Calves-Perthes (LCP), while a 13-year-old boy is more likely to have a slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE). Similarly, transient synovitis is a reasonable consideration for a 5-year-old with fever and hip effusion, but less likely in a 15-year-old with a similar presentation. Radiographs and ultrasound are routinely used for these conditions, and MRI is often a useful adjunct.

DEVELOPMENTAL DYSPLASIA OF THE HIP

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) represents a spectrum of disorders encompassing abnormal acetabular shape and subluxation or dislocation of the femoral head. Typically, DDH is a combination of structural and ligamentous laxity resulting in an incongruent acetabulofemoral joint.1 Reported prevalence of hip instability in neonates ranges from 1.6 to 28.5 per 1,000 live births.2 DDH is six times more common in girls than boys. It is also more common in the left hip (60% of cases) than the right (20%) and bilateral in 20% of patients. Additional risk factors include family history of DDH, firstborn infants, breech presentation, and oligohydramnios.1,3 Presenting signs and symptoms may include the Barlow and Ortolani signs, limited range of hip motion, abnormal skin creases, and unequal limb lengths.1, 2, 3 and 4

The precise etiology for DDH is not fully clarified but is likely multifactorial. Prenatal mechanical factors (e.g., oligohydramnios, less uterine flexibility for primiparous women, breech presentation) combine with ligamentous laxity related to sensitivity to maternal hormones, particularly in girls.1, 2, 3 and 4 Contributing postnatal factors may include methods of wrapping or swaddling infants with the hips in extension.1,4 Over time, sustained malposition of the femoral head inhibits normal development of the acetabulum, resulting in hip dysplasia. A variety of other pediatric disorders feature DDH as a comorbidity, apart from this neonatal presentation. These include cerebral palsy, neural tube defects, and arthrogryposis, among others.4

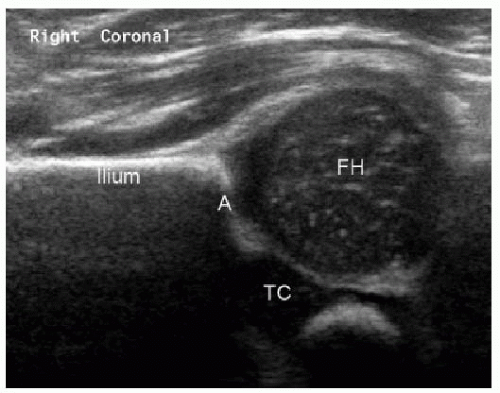

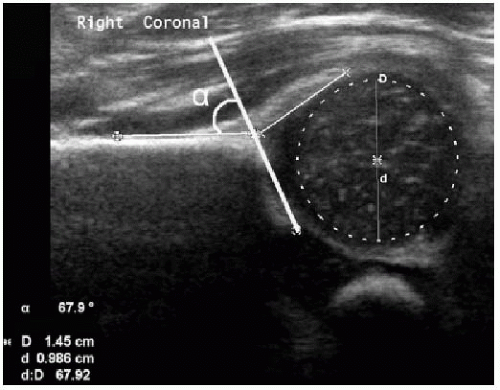

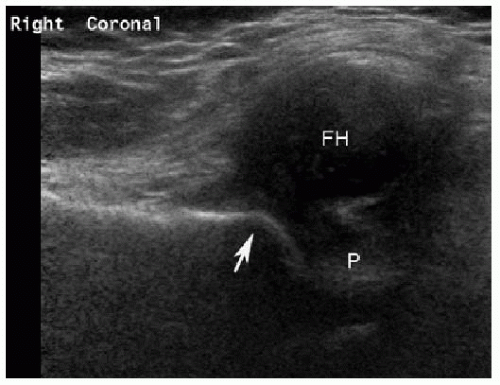

Ultrasound with a high-frequency linear transducer is used to evaluate for DDH in infants younger than 4 to 6 months. Because there is physiologic neonatal ligamentous laxity related to maternal hormones, it is best to start screening hips with ultrasound (US) at 4 to 6 weeks of age. The examination consists of both static (anatomic) and dynamic (physiologic stress) components. The static hip images are acquired in the coronal plane, simulating an AP pelvic radiograph tilted 90 degrees (Fig. 27.1). The ilium appears as a horizontal echogenic line and should normally bisect the cartilaginous femoral head, which has a speckled hypoechoic echotexture. Normal femoral head coverage exceeds 50%, with smaller percentages indicating lateral subluxation until acetabulofemoral contact is lost (dislocation) (Figs. 27.2 and 27.3). The alpha angle is the slope of the acetabular roof with respect to the ilium on the coronal image. Normal alpha angles are greater than 60 degrees. The term “functional immaturity” is often applied when femoral head coverage is 40% to 50% or the alpha angle is 50 to 60 degrees in an infant less than 12 weeks of age. These measurements often spontaneously normalize by 12 weeks of age upon repeat evaluation. Additional gray-scale findings of DDH include blunting of the acetabular corner and hypertrophy of the echogenic

pulvinar (Fig. 27.3). Dynamic hip imaging includes stress maneuvers that simulate Ortolani and Barlow tests. Stress is applied to the hip with the transducer in the transverse plane. If there is joint laxity, then the femoral head subluxes or dislocates posterolaterally with stress.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7

pulvinar (Fig. 27.3). Dynamic hip imaging includes stress maneuvers that simulate Ortolani and Barlow tests. Stress is applied to the hip with the transducer in the transverse plane. If there is joint laxity, then the femoral head subluxes or dislocates posterolaterally with stress.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7

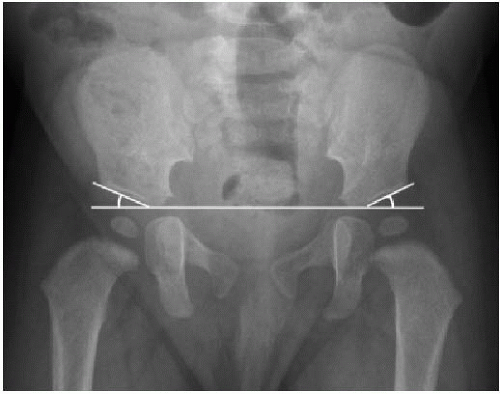

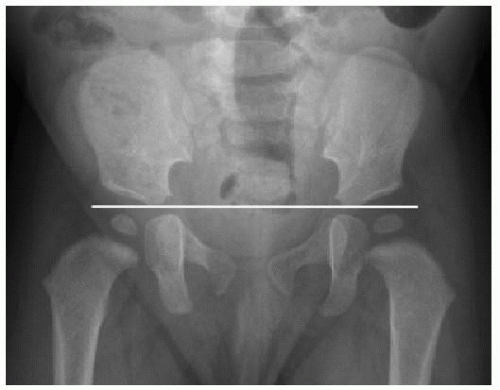

For children older than 4 months, pelvic radiographs are performed instead of US because the femoral head typically has begun ossifying by that time.4 On the AP projection, it is helpful to draw several lines to evaluate hip position, in addition to globally assessing the pelvis. The Hilgenreiner line passes horizontally between the superior aspects of bilateral triradiate cartilages (Fig. 27.4). The lucent triradiate cartilage forms the medial acetabular wall. Another line is drawn connecting the inferomedial and superolateral aspects of the acetabular roof. The acetabular angle or index is formed between this second line and the Hilgenreiner line (Fig. 27.5). The maximum normal acetabular angle is 30 degrees after age 12-16 weeks, and decreases to 25 degrees in children up to 2 years. The Perkin line is drawn vertically from the superolateral acetabular margin to intersect Hilgenreiner line (perpendicular to the horizontal line) (Fig. 27.6). The ossified femoral head is normally located medial and inferior to the intersection of the Hilgenreiner and Perkin lines. When the femoral head is not ossified, the Perkin line should intersect the middle third of the proximal femoral metaphysis. Finally, the Shenton line should smoothly arc along the lesser trochanter, medial femoral neck, and lower margin of the superior pubic

ramus without interruption (Fig. 27.7). When DDH is advanced or untreated, the typical AP radiographic findings are a shallow acetabulum with an index exceeding 30 degrees and superolateral subluxation of the femoral head with delayed ossification (Fig. 27.8).1, 2, 3, 4 and 5,8

ramus without interruption (Fig. 27.7). When DDH is advanced or untreated, the typical AP radiographic findings are a shallow acetabulum with an index exceeding 30 degrees and superolateral subluxation of the femoral head with delayed ossification (Fig. 27.8).1, 2, 3, 4 and 5,8

FIG. 27.4 • Hilgenreiner line in a normal AP pelvis radiograph. This line passes horizontally between the superior aspects of bilateral triradiate cartilages. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree