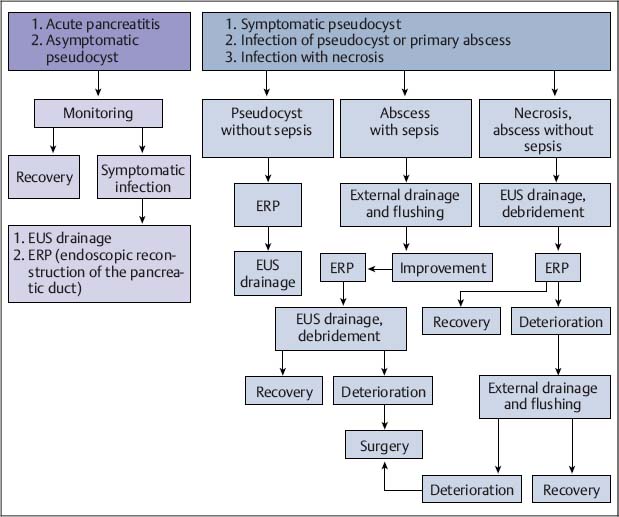

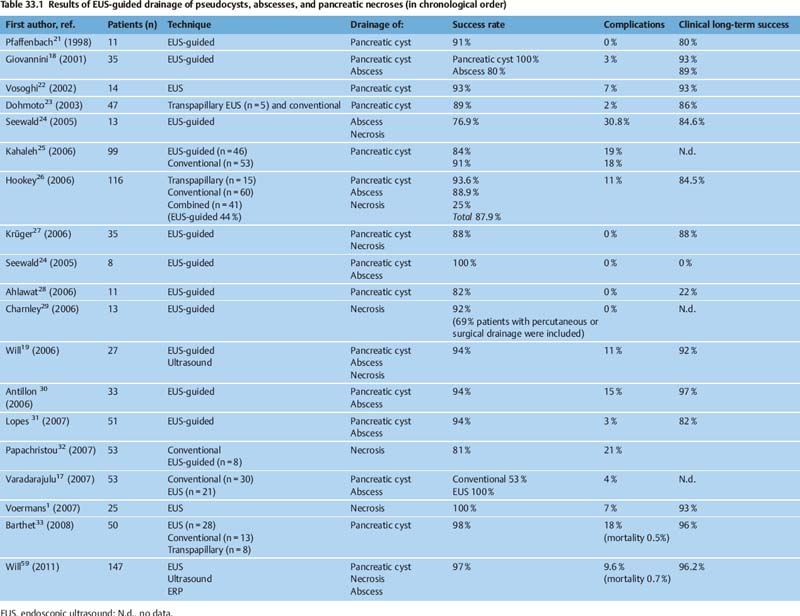

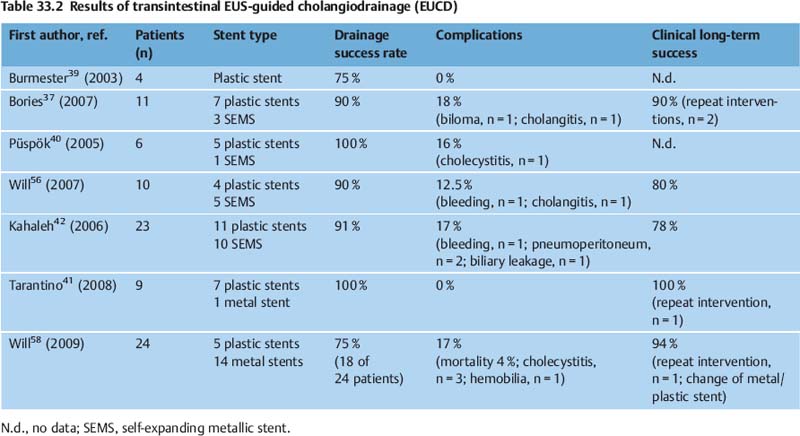

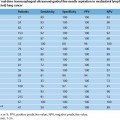

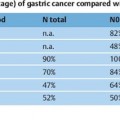

33 Hot Topics in Interventional EUS The range of interventional endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) techniques has expanded enormously during the last 10 years, and there has been growing interest throughout the world in novel interventional approaches using EUS. The combination of endoscopy with the tissue differentiation facilities possible with ultrasound, along with interventional options, means that various surgical procedures can be avoided and that potentially dangerous interventions can be carried out with greater safety.1 In addition to outlining EUS-guided treatment for pancreatic pseudocysts, abscesses and necroses, the aims in this overview of the topic are: • To describe novel techniques for EUS-guided internal drainage of the biliary and pancreatic ducts • To emphasize and critically discuss the relevance of these techniques in everyday clinical practice, with a review of recent literature references EUS-Guided Drainage of Pancreatic Pseudocysts, Abscesses, and Necroses Pseudocysts are frequent complications in patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis. Before every endoscopic intervention, these locular fluid collections with a capsule-like margin surrounding them and with no epithelial layer need to be distinguished from neoplastic, cystic pancreatic lesions. This can be achieved by correlating the clinical symptomatology, EUS morphology, and laboratory and cytological analysis of the cyst fluid. With its outstanding capacity for tissue differentiation in local imaging in comparison with other imaging procedures, along with integrated color-coded Doppler ultrasonography and the option for targeted fine-needle aspiration, EUS has the advantage that it allows precise classification of the various types of pancreatic cysts and lesions.2–5 Cystic neoplasms have a different sonomorphology in comparison with pancreatic pseudocysts. In addition to solid polycyclic tumors growing on the intraluminal side and indicated by wall thickening, enlarged intracystic septa can be detected, and atypical vascular patterns can also be displayed using color-coded Doppler ultrasound. Uncomplicated pseudocysts are commonly characterized by a flat wall with no fluid signals and an echo-free or slightly echogenic and homogeneous fluid. Sequestra and necroses in complicated pseudocysts mostly consist of sediment, and no vessels can be detected with color-coded ultrasound. In these cases, the cystic fluid often has a mixed echogenic and inhomogeneous appearance. If there is any doubt about the specific entity present on the basis of the EUS morphology, primary EUS-guided internal drainage should be avoided and the cystic fluid should be sampled using EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) for cytologic examination, laboratory analysis (for carcinoem-bryonic antigen, CA19-9, and lipase), and microbiological analysis.2,6–13 A detection rate in the range of 75–95 % for cystic neoplasia has been reported with EUS-FNA and cystic fluid analysis. With regard to treatment for pseudocysts, endoscopic internal drainage should only be carried out with symptomatic cysts.5,14–16,60 If a transpapillary drain cannot be placed and if the classic bulging sign is absent, conventional endoscopic drainage is not possible.15 EUS can precisely depict the local relationship between pseudocysts and the gastric or duodenal wall. Intramural or periluminal vessels that may bleed during interventions can be detected and avoided when a drain is being placed. EUS-guided drainage is not appropriate for impressions on the wall of the stomach or small intestine. Numerous EUS-based techniques for internal drainage of cysts and abscesses have been reported in the literature and cannot be discussed here in detail.1,5,15–19 In recent years, a simple and reproducible technique with a low complication rate has been established, which is preferred by the majority of endoscopic ultrasonographers and is described below. Puncture is carried out after EUS examination at a site in which needle penetration will not affect high-risk anatomic structures—for example, when there are no vessels along the puncture track and when the transluminal distance to the cyst is very short. Intervention with fluoroscopic guidance is recommended, firstly to allow the position of the endoscope to be identified before puncture and secondly to allow a guide wire to be introduced after puncture with a 19-G needle. Knowing the endoscope’s position is important to allow the endoscopist to carry out subsequent interventions easily, such as transgastric endoscopic debridement in infected necroses. A heavily angled EUS instrument can make subsequent transgastric repeat interventions considerably more difficult. Following EUS-guided puncture of the cyst, the further approach has to be decided in accordance with the clinical symptoms, EUS morphology, and the consistency of the cystic fluid. If there is a noninfectious cyst with clear cystic fluid and an echo-free pattern, an 8.5-Fr or 10-Fr prosthesis can be placed after a wire-guided cystostomy using a diathermy knife. If possible, pigtail prostheses should be used in order to avoid dislocation of the prosthesis. If there is any evidence of an infectious cyst or even an abscess, the ostium of the cystogastroenterostomy can be dilated atraumatically up to a diameter of 10–20 mm with a dilation balloon via the guide wire, which is still in place. To keep the cystoenterostomy open and maintain access to the abscess or necrotic cavity, placement of two or three (8.5–10-Fr) pigtail drains is recommended. Introducing a nasogastric rinsing tube along with percutaneous external rinsing drainage, which is comfortable for the patient, can accelerate the removal of adherent necrotic sequestra in case of infected necroses, minimizing the number of endoscopic interventions needed. There have as yet been no controlled studies on the results with this type of combined approach. A survey of members of the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) on the value and importance of EUS in the treatment of pseudocysts showed that only 70 % of American endoscopists and 59 % of non-American endoscopists use EUS with diagnostic intent before endoscopic drainage of pseudocysts or cysts.20 This was a surprising finding, as it has been shown in numerous studies that conventional endoscopic drainage of a pseudocyst is only successful in 40–57 % of cases (or even zero, for cysts in the pancreatic tail), while drainage is successfully achieved in 75–97 % of cases, independent of the cyst site, when EUS is used.1,2,17–19,21–33 In a comparative study by Varadarajulu et al.,17 a primary endoscopic attempt to place a drain failed in 23 of 53 patients. Subsequent EUS-guided drainage was successful in all of the patients. With improved training for gastroenterologists in the field of interventional EUS, along with the convincing success rates achieved and reported at the major EUS centers, EUS-guided drainage of cysts, abscesses, and encapsulated necroses has become the preferred method of treatment. In addition to providing better differentiation between pseudocysts and cystic neoplasia with color-coded Doppler ultrasound and FNA, EUS makes it possible to treat peripancreatic fluid collections with a low complication rate and expands the endoscopic treatment options available for patients with abscesses or necroses. Table 33.1 lists the results of large case series on EUS-guided drainage of pseudocysts, abscesses, and encapsulated necroses. The complication rates are low (0–21 %). In addition to hemorrhage and cystic infections (3–15%), perforations have been reported after balloon dilation or endoscopic debridement.1,14,16,25 The long-term clinical success rate of 90% reported in recent studies shows that EUS-guided management is a reasonable approach in the treatment of peripancreatic fluid collections. The central role that EUS plays in the treatment of pseudocysts, abscesses, and necroses is indicated in Fig. 33.1. The recognized treatment methods depend on the specific diseases and clinical symptoms, leading to a treatment algorithm that can be varied in accordance with the clinical course. Percutaneous cholangiography drainage (PTCD) is used in most gastroenterological centers as an alternative in patients in whom endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) has failed due to malignant obstructive diseases. In addition to having a higher complication rate in comparison with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), PTCD is unable to achieve external or internal drainage in all cases.34–36 Solely external drainage disturbs the patient’s physical integrity, which can become a substantial psychological problem in those with advanced or metastatic malignant disease and limited life expectancy, in addition to the disadvantage of a permanent loss of bile. The basic aim is to achieve adequate, permanent, and if possible internal drainage of the biliary tree as part of a palliative therapeutic approach in patients with malignant, incurable disease and obstructive, tumor-induced jaundice. The treatment should be associated with a low complication rate and should not require any further repeat interventions during the patient’s life. The results of large case series have shown that EUS-guided cholangio-drainage (EUCD) is a treatment method that is capable of achieving these aims.19,25,37,61 The first EUS-guided cholangiography procedure was reported by Wiersema et al. in 1996,38 and the first larger case series on EUS-guided cholangiodrainage was published by Burmester et al. in 20 03.39 Larger case series in recent years have shown that a technical success rate with EUCD in the range of 75–100%, along with low complication rates (0–18%), can be achieved19,25,37,39–43 (Table 33.2). However, there is still a lack of controlled and randomized studies comparing EUCD with PTCD and ERCP. The groups of patients treated in the case series are very heterogeneous. While Bories et al.37 and Will et al.43 only treated patients with advanced malignant disease, Kahaleh et al.42 and Tarantino et al.41 also included patients with benign diseases. This makes meaningful comparison of the long-term results difficult. The studies show that EUCD is indicated in patients with obstructive cholestatic disease in whom ERCP and internal drainage cannot be achieved for anatomic reasons or due to progressive tumor growth (following a previous gastrectomy, Whipple procedure, tumor-induced gastric outlet syndrome, previous hepaticojejunostomy, or inability to introduce the catheter into the papilla). Two EUS-guided approaches are in principle possible: •

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree