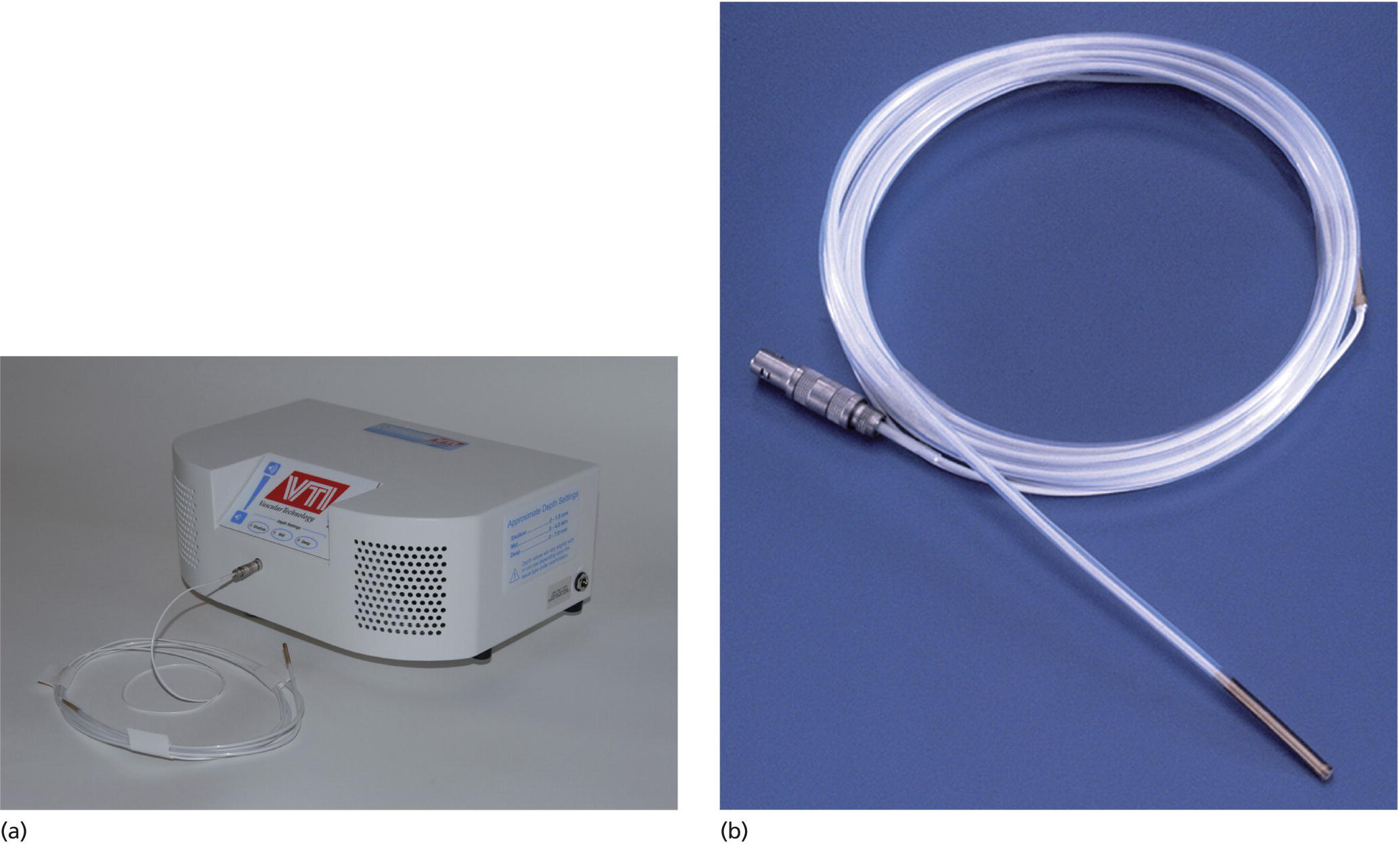

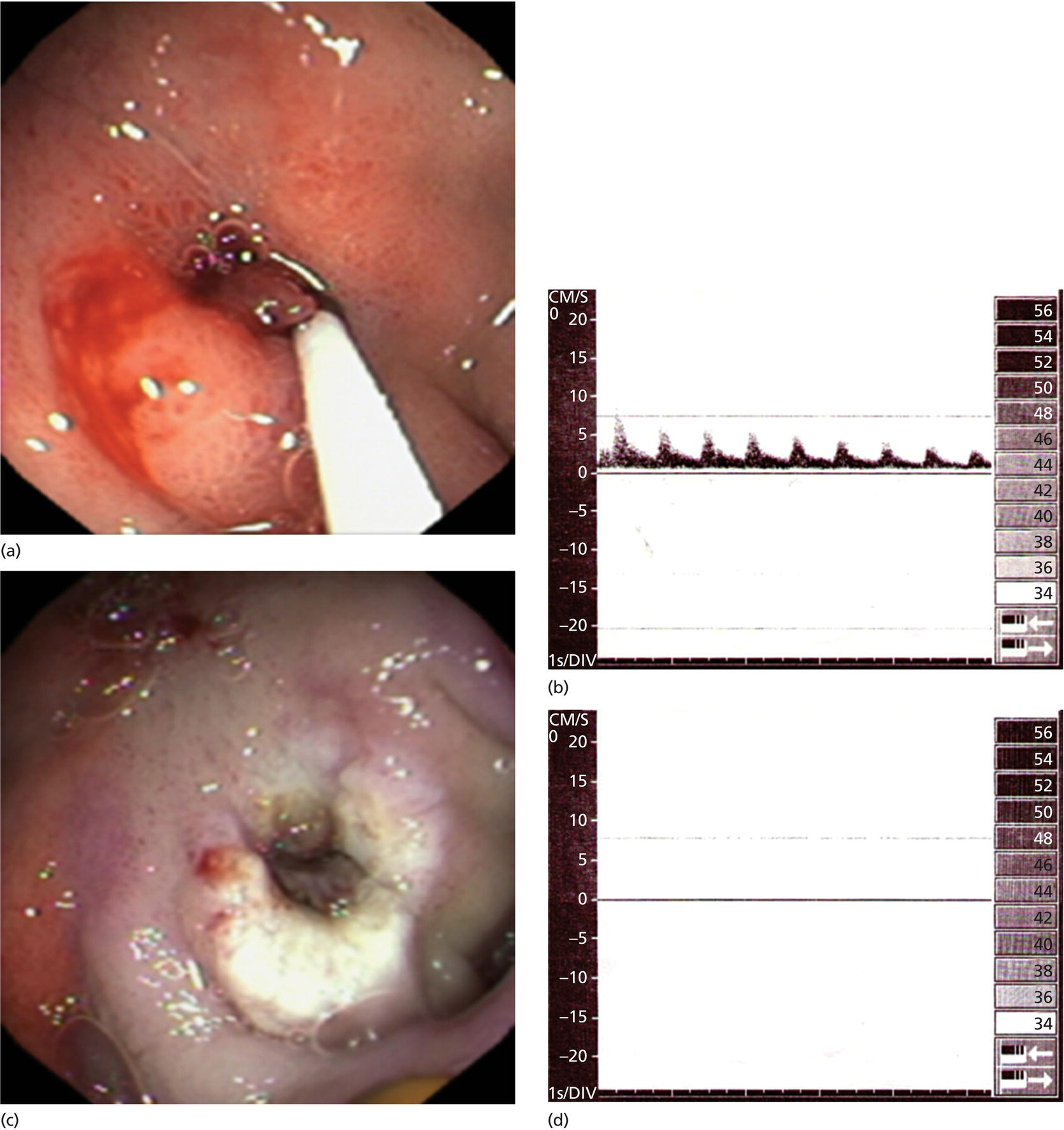

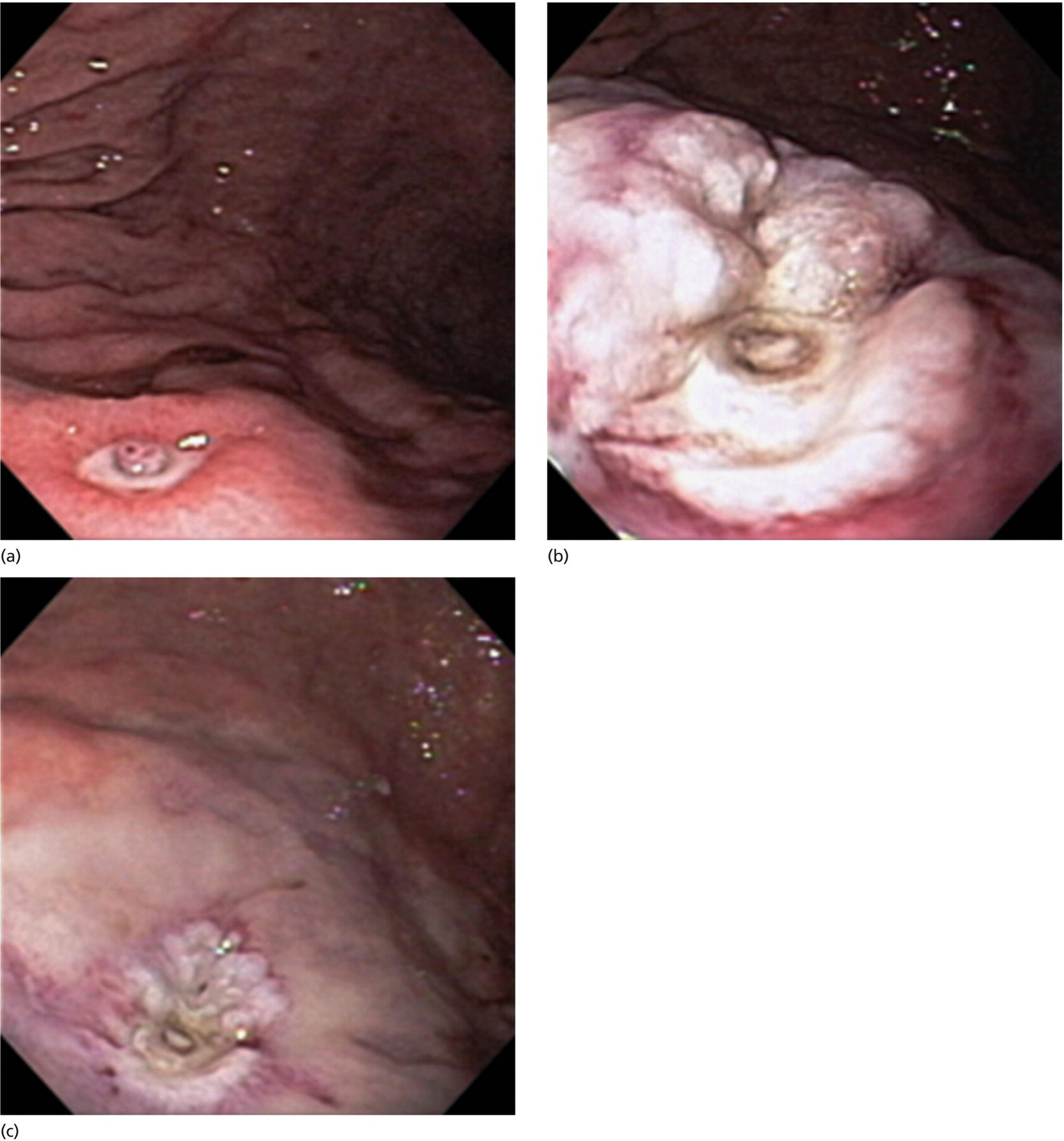

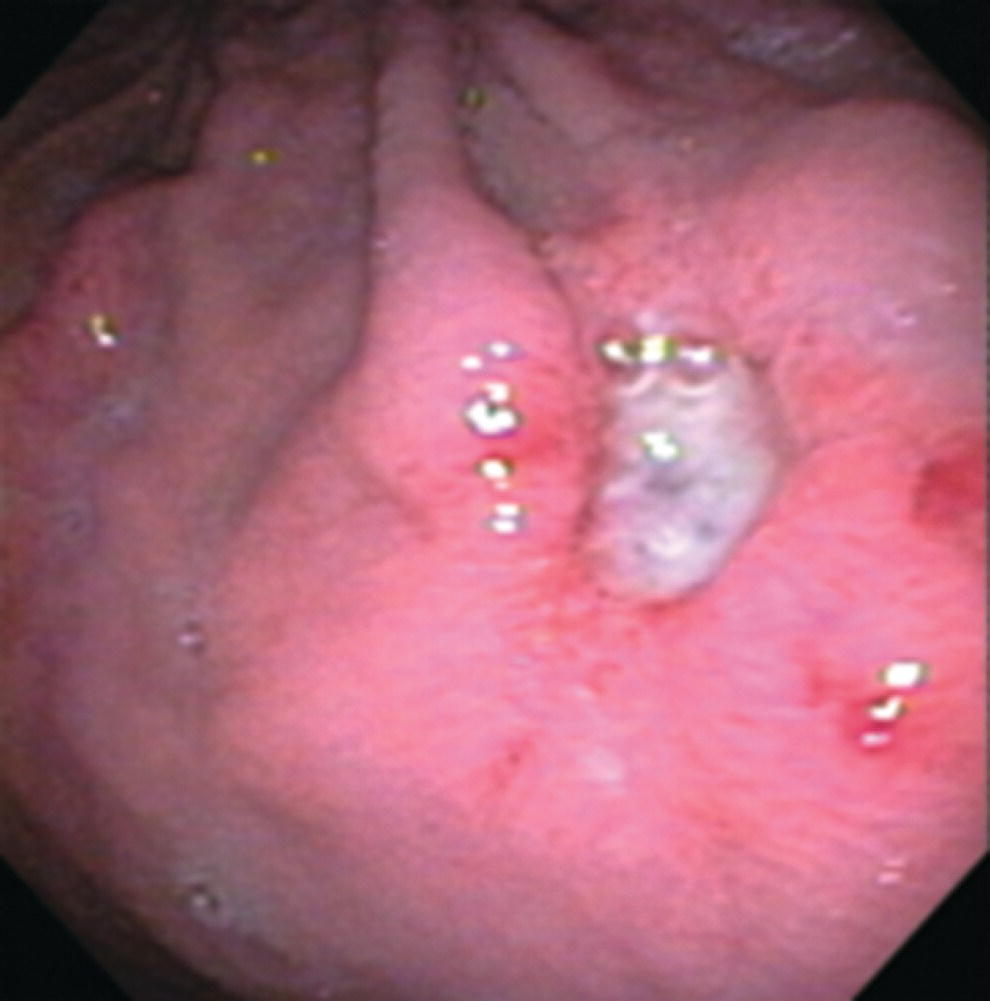

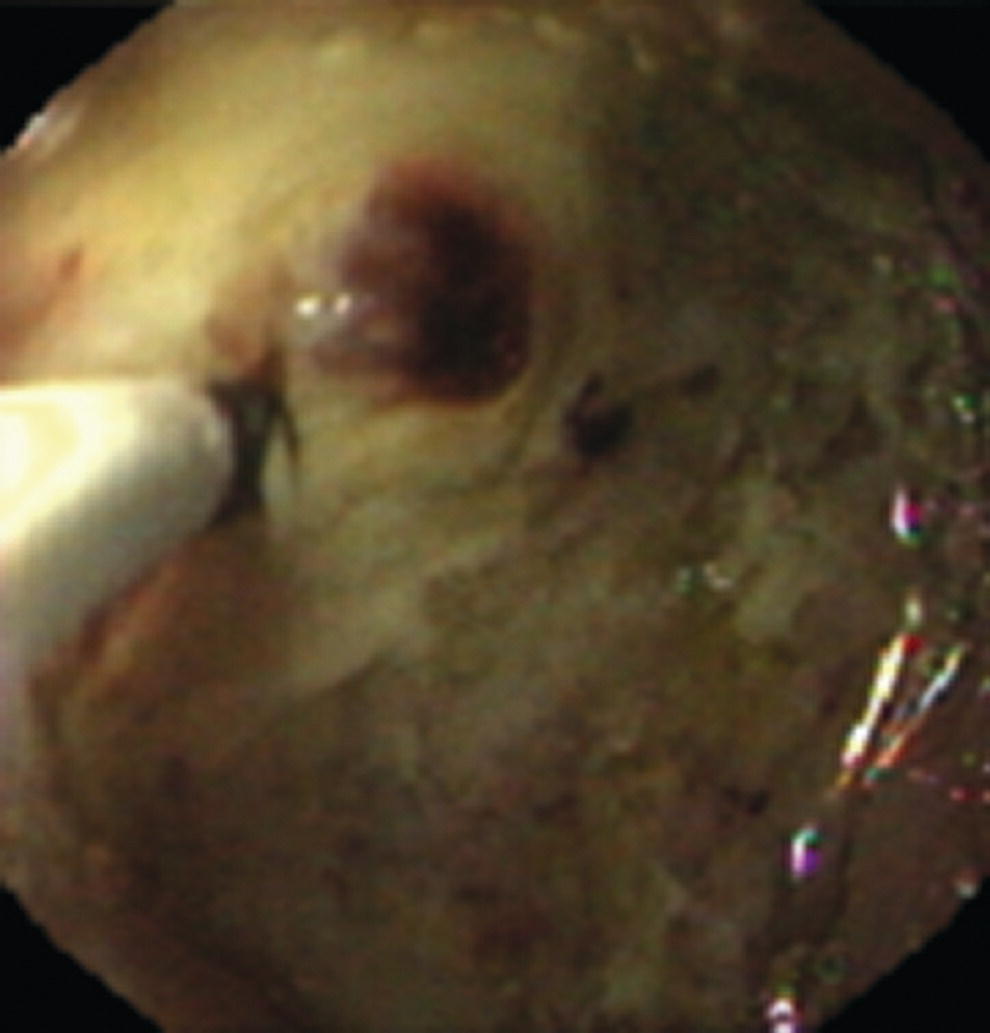

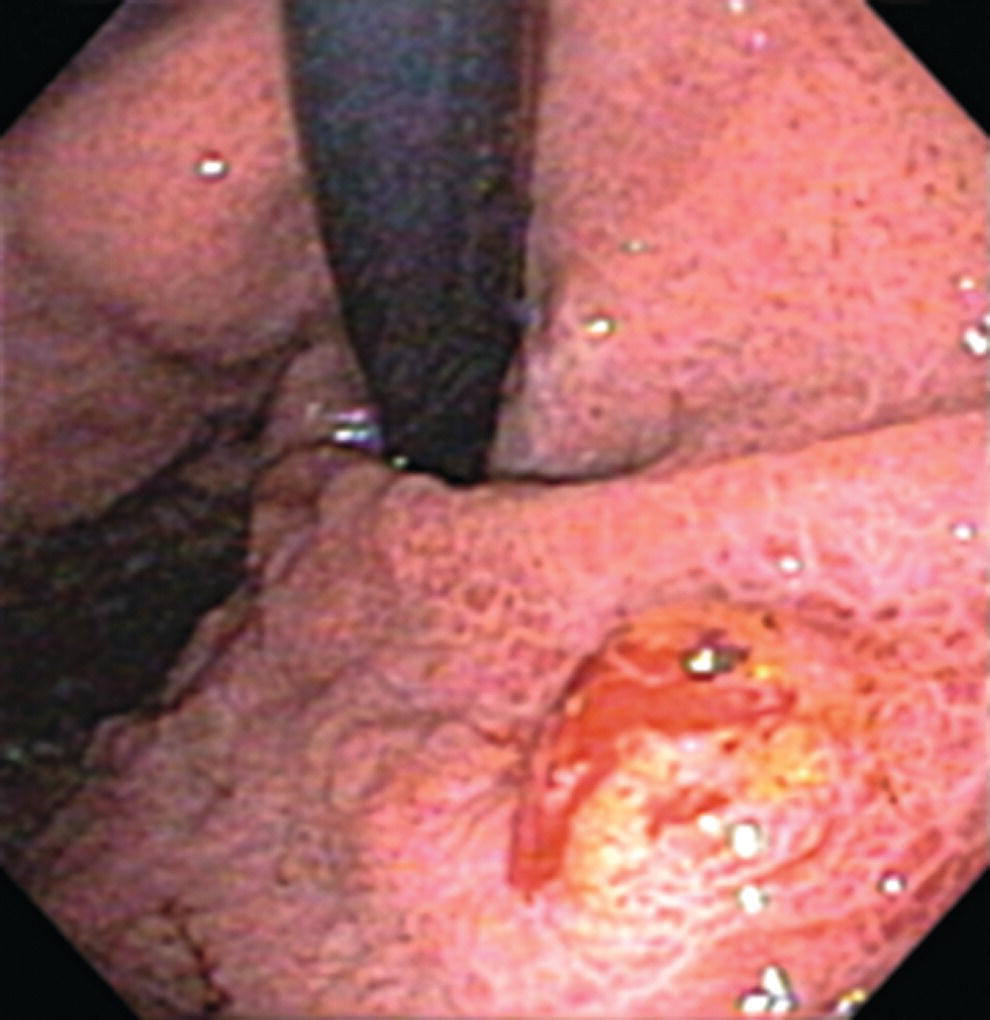

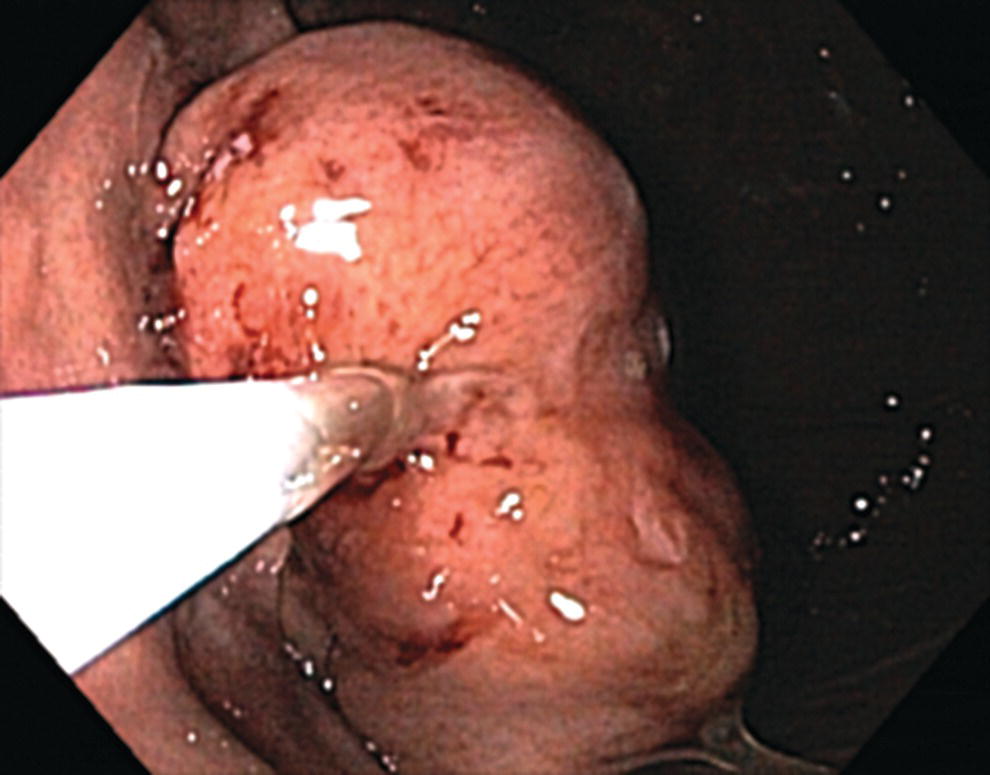

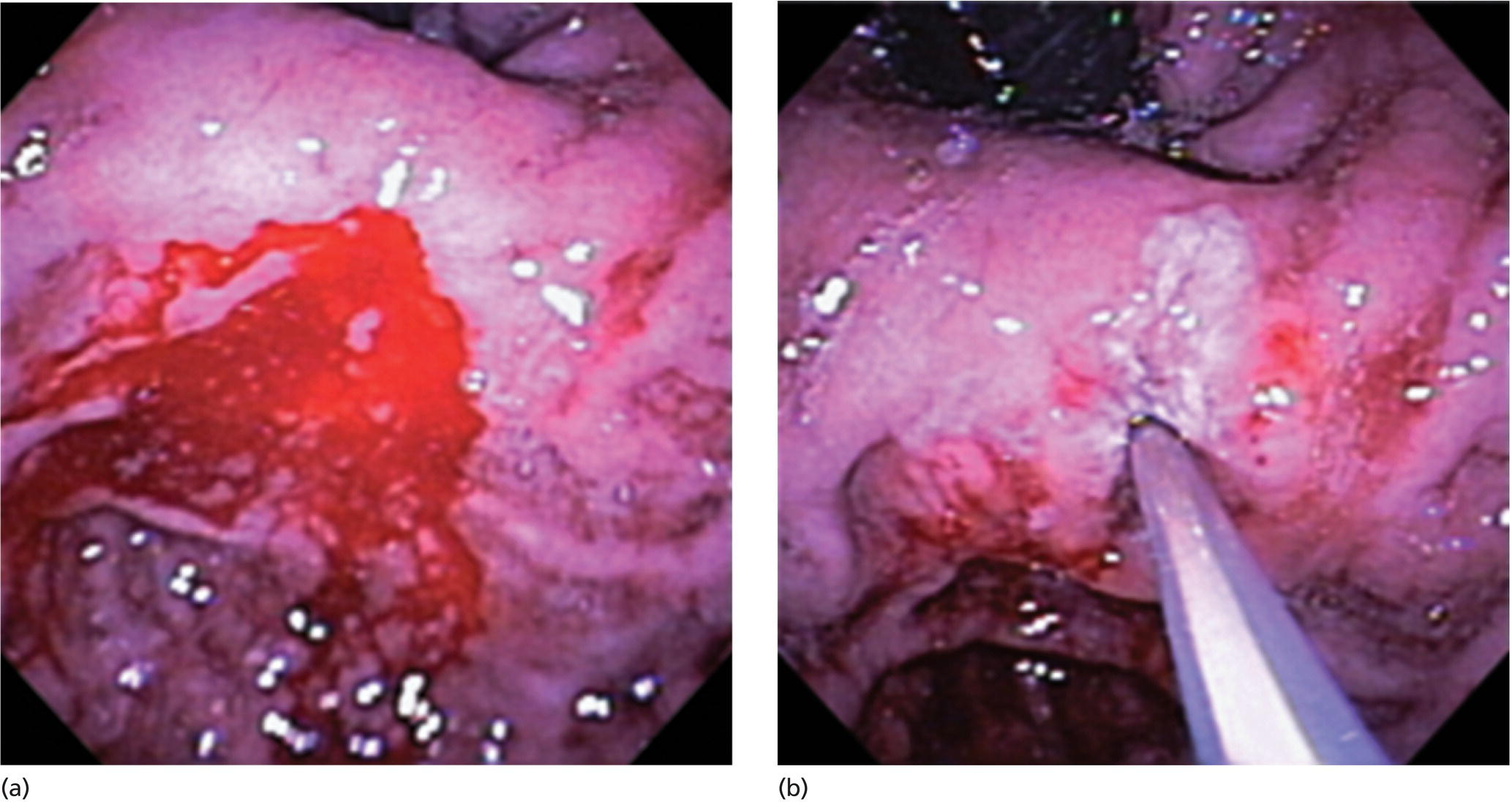

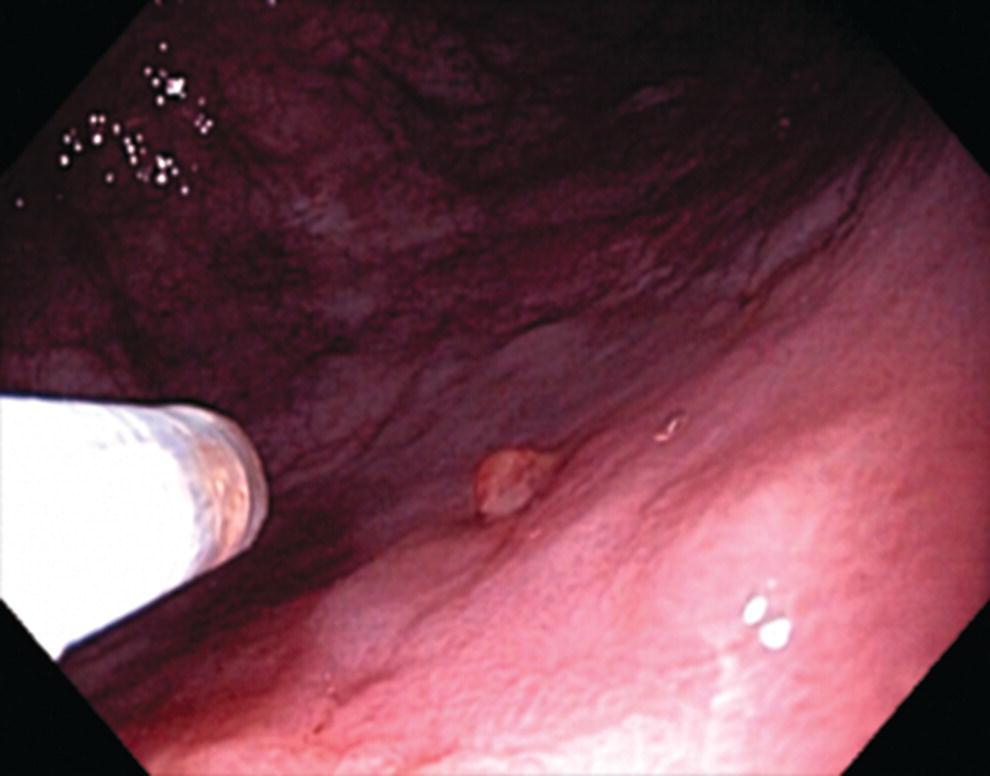

Richard C.K. Wong Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals Case Medical Center, Cleveland, OH, USA Doppler ultrasound, particularly use of the endoscopic Doppler ultrasound (DopUS) probe, is quite different from traditional endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and miniature EUS probes inasmuch that the currently available DopUS probe is non‐imaging, the equipment is portable and significantly less expensive than EUS systems, and advanced endoscopic training in traditional EUS is not required. In addition, because the DopUS probe makes direct physical contact with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract lesion of interest, acoustic coupling with instilled water or with a water‐filled balloon are not required. Signal output from the non‐imaging DopUS probe system is in the form of an audible Doppler ultrasound signal with or without graphic display of the acoustic Doppler ultrasound waveform. Within the last decade, two DopUS systems have been utilized in published studies: Endo‐Dop (DWL GmbH, Singen, Germany) and VTI Endoscopic Doppler System (Vascular Technology Inc., Nashua, NH) (Figures 39.1 and 39.2). However, only the VTI system has received US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance for use in GI endoscopy in the United States. Both systems are AC powered. Advanced endoscopic training, detailed knowledge of EUS, or specific training in EUS is not required to use DopUS. The technique of DopUS can be readily acquired by most GI endoscopists in a relatively short time. Modern DopUS probe systems utilize pulsed‐wave ultrasound technology, which allows the endoscopist to vary scanning depth, to select the most appropriate depth for the specific bleeding lesion of interest, and to exclude deep serosal vessels (“innocent bystanders”) that are not involved in the bleeding process. Available DopUS systems are small and portable, and can be easily placed on an emergency endoscopy cart for patients located in intensive care units or in operating rooms. With current DopUS probe technology, a 16‐ or 20‐MHz pulsed‐wave ultrasound beam is emitted in a linear fashion from the distal tip of a small flexible probe that is passed down the accessory channel of a standard diagnostic (or therapeutic) forward‐viewing (or side‐viewing) endoscope to make direct physical contact with the GI tract lesion of interest. It is important to select the scanning depth based on the lesion of interest: shallow (0–1.5 mm) for peptic ulcers versus mid (0–4 mm) for varices. Depending on the manufacturer, DopUS probes are marketed either as disposable, single‐use only, or reusable after gas sterilization or high‐level liquid disinfection. Before each use, it is important to perform a preprocedure check to ensure that the DopUS system is functioning appropriately. This is done by first connecting the DopUS probe to the base unit, turning the power on, and tapping the distal probe tip gently with an ungloved finger. In an appropriately functioning system, a corresponding tapping sound should be heard. In units that allow for adjustment of sound volume, this should be kept at maximum. The preprocedure system check is then completed. Note that the system should be turned off before passing the probe through the accessory channel of the endoscope. Figure 39.1 VTI endoscopic Doppler system. (a) A 20‐MHz pulsed‐wave Doppler ultrasound system. Doppler ultrasound output signal: audible only. Weight: 1.18 kg. United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance: yes. (b) Doppler ultrasound probe: single‐use, probe diameter 2.5 mm, lengths 165 cm and 245 cm. Source: reproduced by permission of Vascular Technology, Inc., Nashua, NH. Figure 39.2 Endo‐Dop, 16‐MHz pulsed‐wave, multigated Doppler ultrasound (DopUS) system with reusable DopUS probe and optional foot pedal. Doppler US output signal: visual and audible. Weight: 6.76 kg. United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance: no. Source: reproduced by permission of Elsevier. Published studies using the DopUS probe in acute peptic ulcer bleeding have demonstrated the following. Figure 39.3 Illustration of a bleeding peptic ulcer with a non‐bleeding visible vessel (NBVV) undergoing Doppler ultrasound (DopUS) examination using an endoscopic DopUS probe that was passed via the accessory channel of a standard endoscope. Source: Wong RCK. Risk stratification of nonvariceal UGI hemorrhage for the practicing endoscopist. Tech Gastrointest Endosc 2005;7(3):118–123. © 2005, Elsevier. Figure 39.4 Doppler ultrasound (DopUS) in acute peptic ulcer bleeding. (a) Endoscopic image of a DopUS probe on a bleeding duodenal ulcer with a non‐bleeding visible vessel: Doppler positive. (b) Visual graphic display of the corresponding positive DopUS signal: y‐axis, frequency shift (kHz); x‐axis, time (s). (c) Endoscopic image of the same ulcer after combination endoscopic therapy with epinephrine injection and heat probe: Doppler negative. (d) Visual graphic display of the corresponding negative DopUS signal. Source: (b, d) Wong RCK. Endoscopic Doppler US probe for acute peptic ulcer hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc 2004;60(5):804–812. © 2004, Elsevier. Figure 39.5 Doppler ultrasound‐guided hemostasis in acute peptic ulcer bleeding. (a) Gastric ulcer with a non‐bleeding visible vessel: Doppler positive. (b) Immediately following dual combination endoscopic therapy with epinephrine injection and heat probe: Doppler positive. (c) Targeted, additional heat probe application to location of positive Doppler signal: Doppler negative. No recurrent bleeding at 30 days. Figure 39.6 Atypical peptic ulcer bleeding: recurrent major bleeding from a gastric ulcer, clean base, without stigmata of recent hemorrhage (requiring a 7‐unit blood transfusion in a healthy 23‐year‐old man). Doppler ultrasound (DopUS) localized a strongly positive arterial Doppler at the 11 o’clock position, targeted DopUS‐guided hemostatic therapy was performed with no recurrent bleeding at 30 days. Figure 39.7 Doppler‐negative non‐bleeding visible vessel. Endoscopic image of a Doppler ultrasound probe being placed on an untreated bleeding duodenal ulcer. Table 39.1 Correlation of endoscopic appearance of peptic or anastomotic ulcers with endoscopic Doppler ultrasound signal. Clinical scenarios where use of the endoscopic DopUS probe could be useful include the evaluation of uncertain visual SRH, in the assessment of adequacy of endoscopic hemostatic therapy, and in the evaluation of bleeding ulcers that behave functionally as high risk but which appear to be low risk by visual stigmata alone (e.g. recurrent bleeding from a clean‐based ulcer or ulcer with flat pigmented spot). DopUS probe has been used in the following disorders but further studies are required to evaluate clinical utility. Figure 39.8 Atypical appearance of a bleeding gastric varix. Mild active oozing of blood from a single, small, yellowish submucosal lesion in the gastric fundus, Doppler positive. Source: reproduced by permission of Elsevier. Figure 39.9 Doppler ultrasound examination of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor in the gastric fundus, Doppler negative. Source: reproduced by permission of Elsevier. Figure 39.10 Dieulafoy lesion in gastric cardia. (a) Active bleeding. (b) Doppler ultrasound probe examination immediately following dual combination hemostatic therapy. Figure 39.11 Dieulafoy lesion in rectum, Doppler with strong arterial signal. The endoscopic DopUS probe allows the endoscopist to determine the presence or absence of subsurface blood flow in bleeding lesions, to differentiate between arterial and venous blood flow, to estimate depth of the subsurface blood vessel, and to estimate location of the subsurface blood vessel. Being able to generate such a subsurface map of blood flow could potentially allow for precise targeting and titration of endoscopic hemostatic therapy based not on visual surface stigmata alone, but with additional knowledge of subsurface blood flow. The author has received research funding from Vascular Technology, Inc.

39

How to do Doppler Probe EUS for Bleeding

Background and equipment

Practical application of DopUS probe

Preprocedure system check

Doppler ultrasound signals

Peptic ulcer (Figures 39.3–39.7)

Published studies

Endoscopic appearance

Doppler (+) (%)

Active bleeding (spurting)

100

Active bleeding (oozing)

60

Non‐bleeding visible vessel

44

Adherent clot

14

Flat pigmented spot

9

Clean base

11

Clinical scenarios

Gastric varices versus thickened gastric folds versus gastrointestinal stromal tumor (Figures 39.8 and 39.9)

Miscellaneous disorders

Conclusions

Conflicts of interest disclosure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree