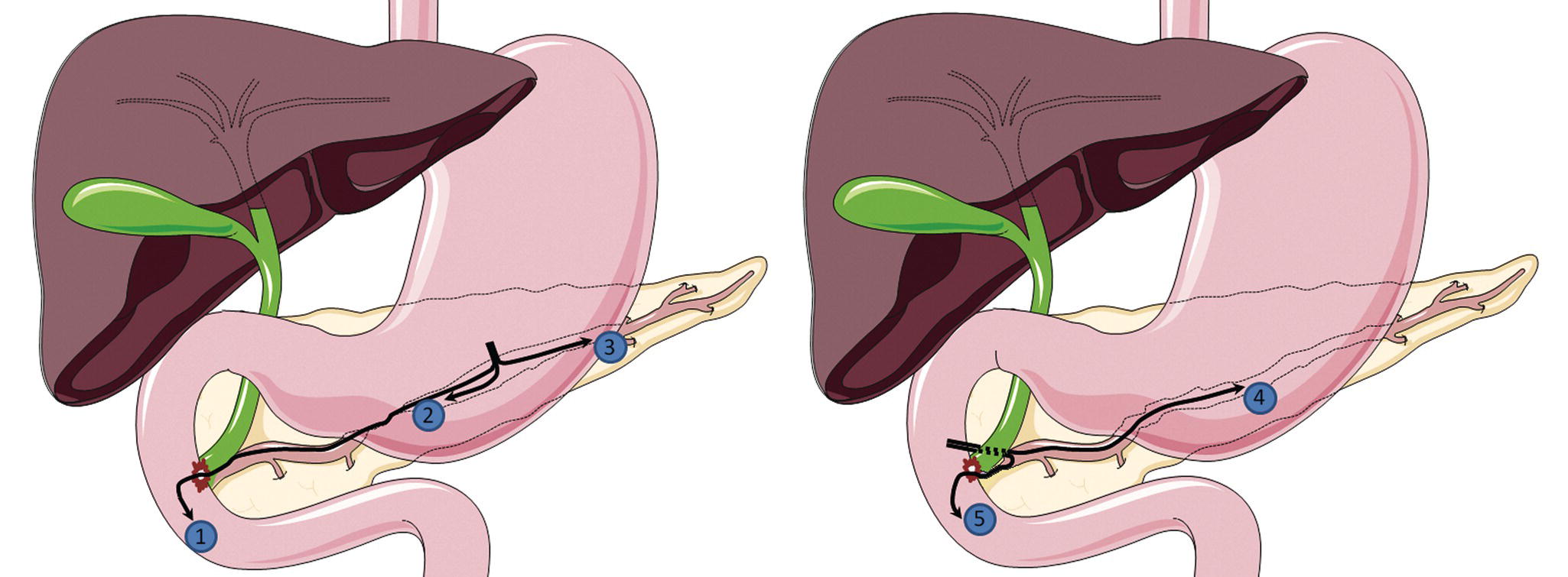

Alberto Larghi1, Mihai Rimba 1 Digestive Endoscopy Unit, Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy 2 Department of Gastroenterology, Colentina Clinical Hospital; Internal Medicine Department, Carol Davila University of Medicine, Bucharest, Romania 3 Digestive Endoscopy Unit, University of São Paulo, SP, Brazil In recent years, technological advancements in endoscopy have allowed minimally invasive interventions to the pancreatic and biliary ductal systems. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is considered a first‐line treatment for main pancreatic duct (MPD) strictures, disruption or obstruction. However, even in expert referral centers, in around 10% of patients ERCP may be impossible due to surgically altered anatomy, or may fail due to inaccessible papilla, tight MPD strictures, pancreatic duct disruption, or other technical and anatomic conditions. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) grants access to a wide variety of procedures. Since the initial description of EUS‐assisted pancreatography by Harada in 1995 and Wiersema in 1996, the procedure has continued to evolve so that even EUS‐guided MPD access and drainage has been performed. Despite the high level of difficulty and very selective indications, EUS‐guided pancreatic duct drainage (EUS‐PDD) is a powerful tool when ERCP is impossible or fails. At present, the generally accepted indications for EUS‐PDD include the following. General contraindications for therapeutic endoscopy apply also to EUS‐PDD. The other contraindications that must be considered include: The procedure should be performed with the patient under general anesthesia. Prophylactic intravenous antibiotics should be administered before EUS‐PDD, and the procedure should be performed using a therapeutic channel echoendoscope utilizing CO2 insufflation. Patient positioning is also important, since the prone position allows easier recognition of the MPD under fluoroscopy guidance. EUS‐PDD can be performed as an anterograde, retrograde, or rendezvous procedure (Figure 45.1). The terms “anterograde” and “retrograde” refer to the direction of stent insertion and drainage. In the anterograde approach, the stent insertion is in the ampulla direction, whereas the retrograde drainage moves toward a caudal path. The MPD can be accessed by the transgastric, transduodenal, or transenteric approach. Figure 45.1 Access points and routes for EUS‐PDD: 1, transgastric rendezvous; 2, transgastric MPD access for antegrade stenting; 3, transgastric MPD access for retrograde stenting; 4, transduodenal MPD access for retrograde stenting; 5, transduodenal rendezvous. Source: Rimbas M, Larghi A. Endoscopic ultrasonography‐guided techniques for accessing and draining the biliary system and the pancreatic duct. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am 2017;27:681–705. © 2017, Elsevier. The procedural steps are very similar to those commonly performed for EUS‐guided biliary drainage. However, EUS‐PDD is definitely more demanding and challenging than EUS‐guided biliary drainage, mainly because the stability of the echoendoscope in the stomach is relatively low and it does not allow application of forces on the different endoscopic accessories that are being used during the procedure. First, four variables must be considered in every procedure: The long scope position with the tip of the echoendoscope in the distal antrum, pyloric ring or duodenal bulb allows better stability and facilitates stent manipulation. The access site for performing puncture should take into consideration the shortest distance between the transducer and the MPD, maximal scope stability, absence of interposed vessels, and angle for tract dilation and stent deployment. To access the MPD, the 19‐gauge fine needle aspiration (FNA) needle is generally utilized since it allows the use of larger‐diameter guidewires that guarantee better stability during stent deployment. Accessing a non‐dilated MPD or traversing a large amount of fibrotic parenchyma can be very challenging. In these cases, puncture can be facilitated using a number of tricks.

45

How to do EUS Pancreatic Duct Access and Drainage

2, and Mauricio K. Minata3

2, and Mauricio K. Minata3

Introduction

Indications

Contraindications

Before the procedure

Techniques for drainage

Needle puncture

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree