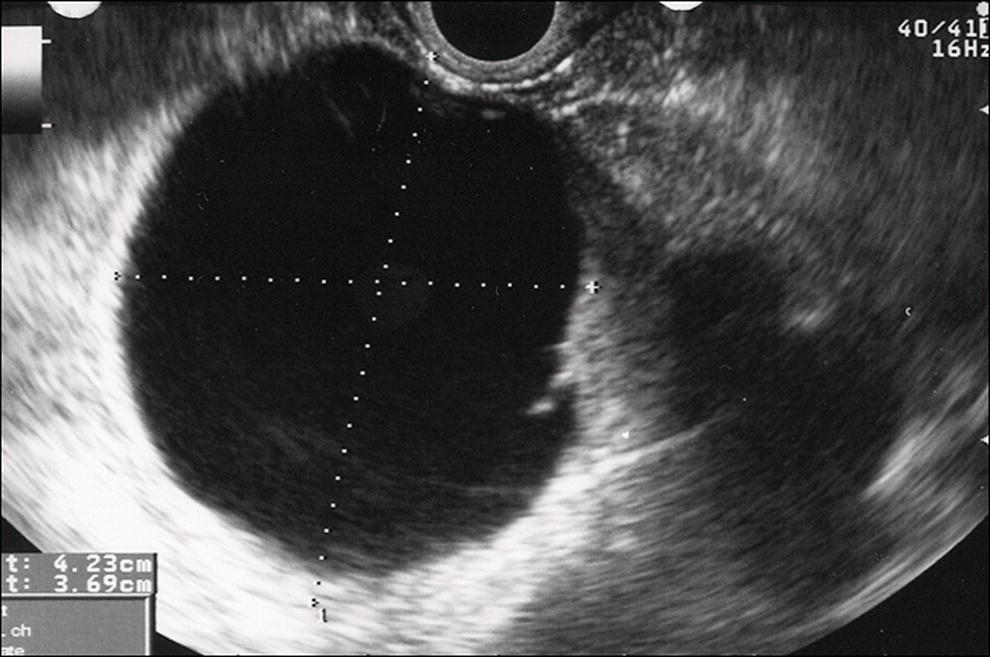

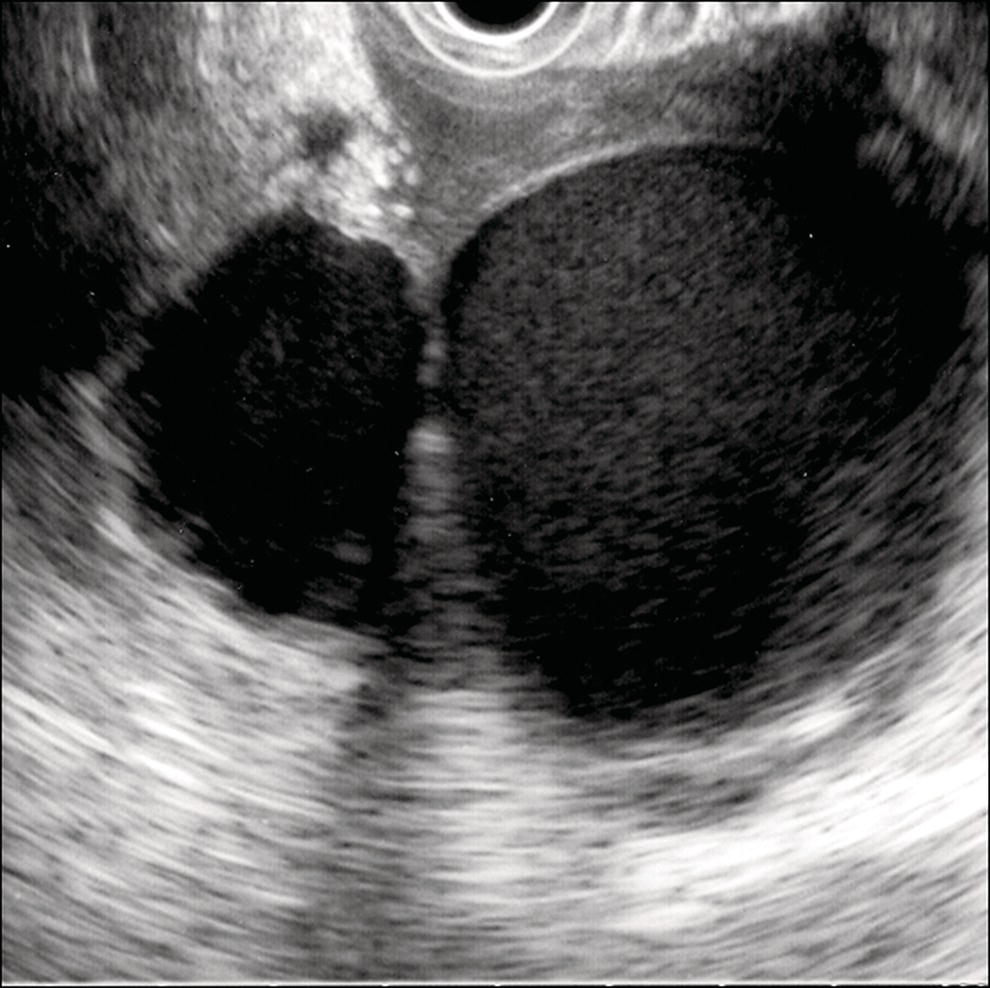

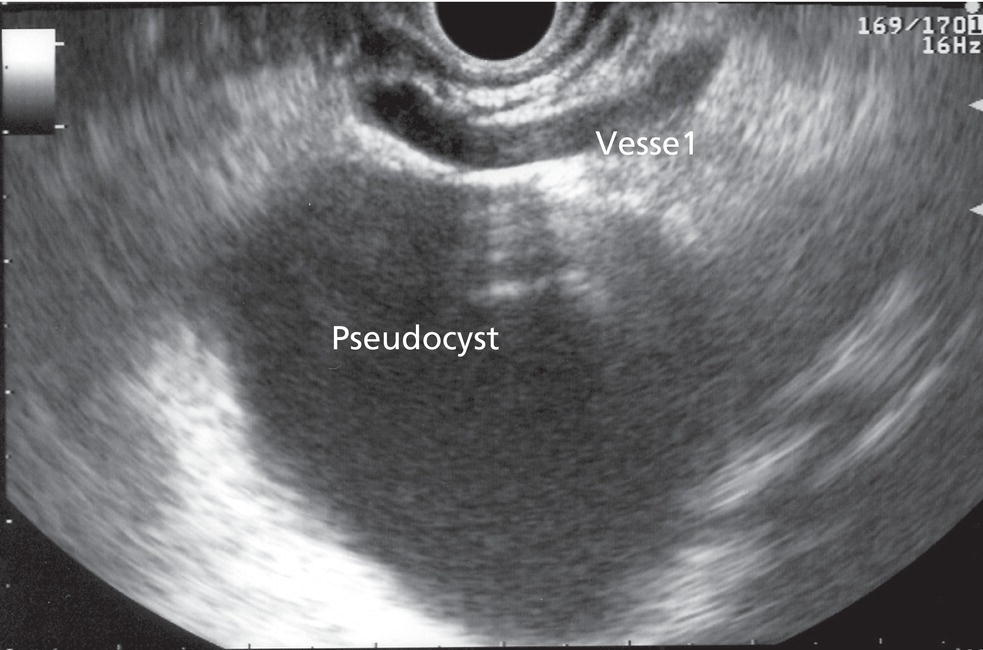

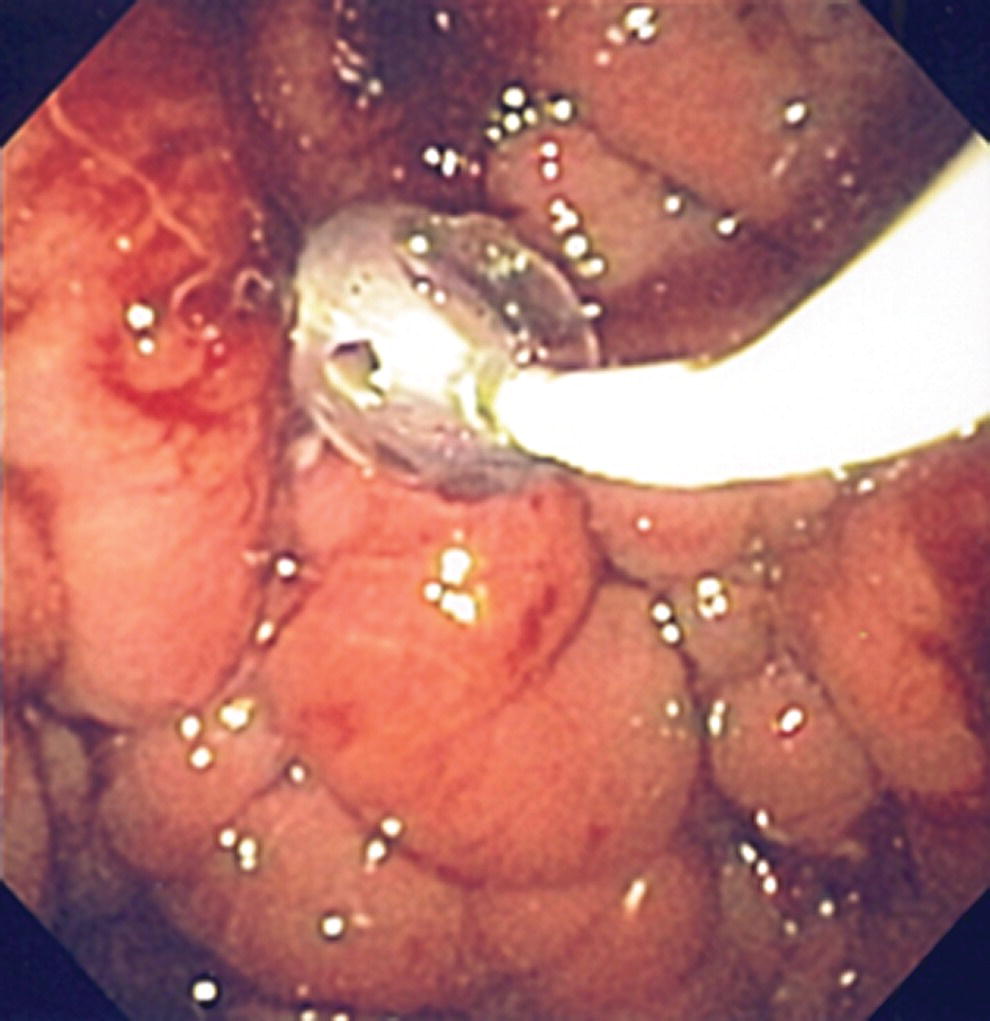

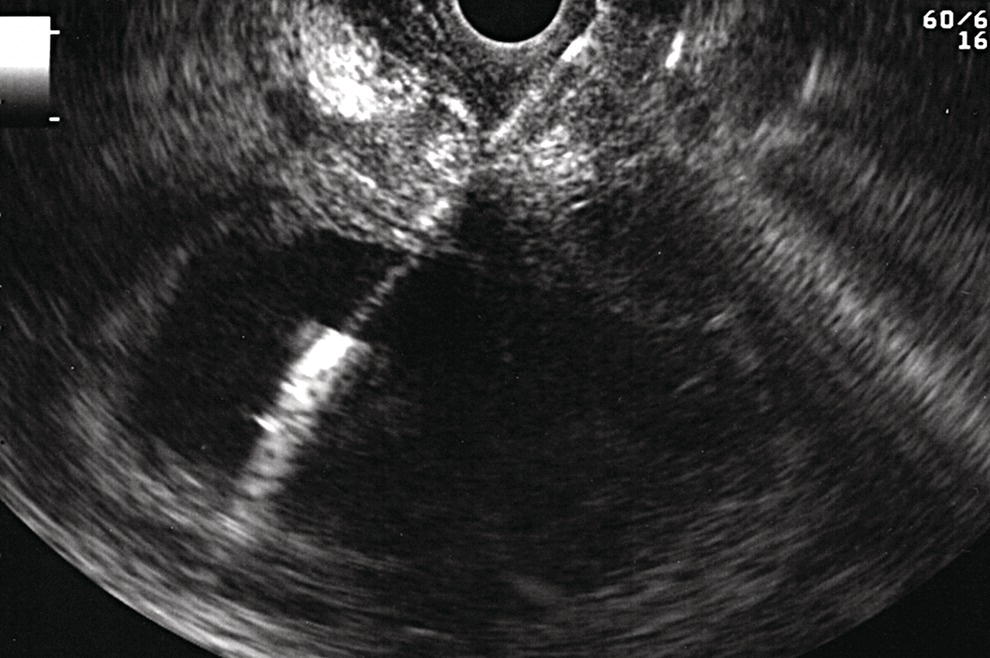

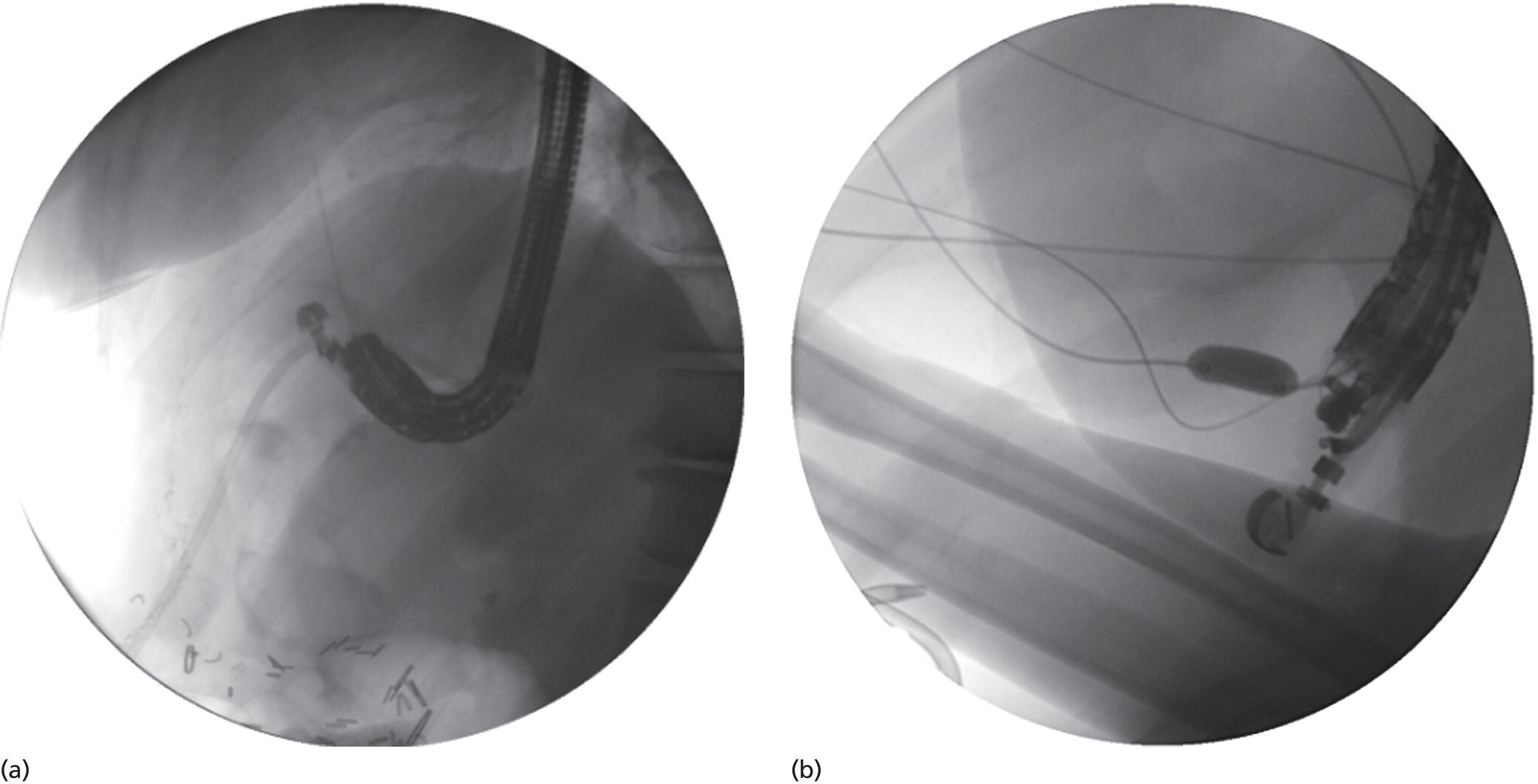

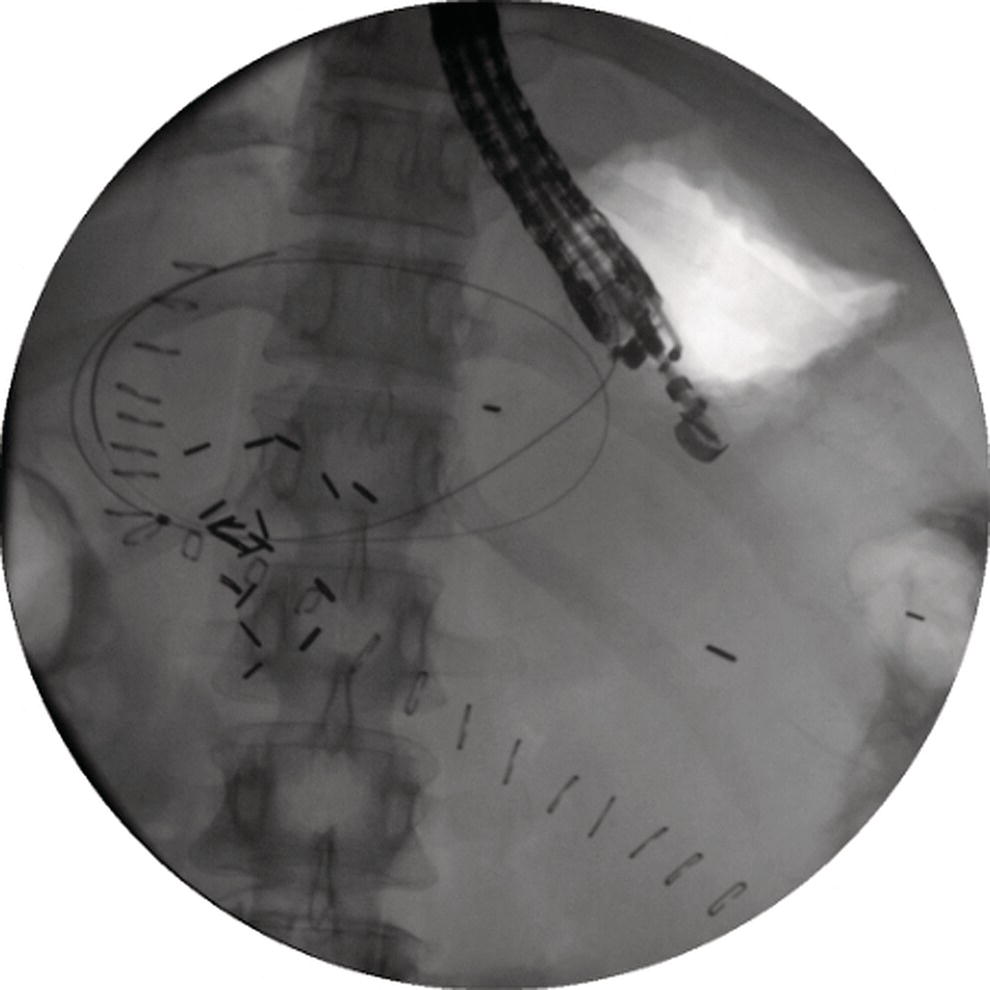

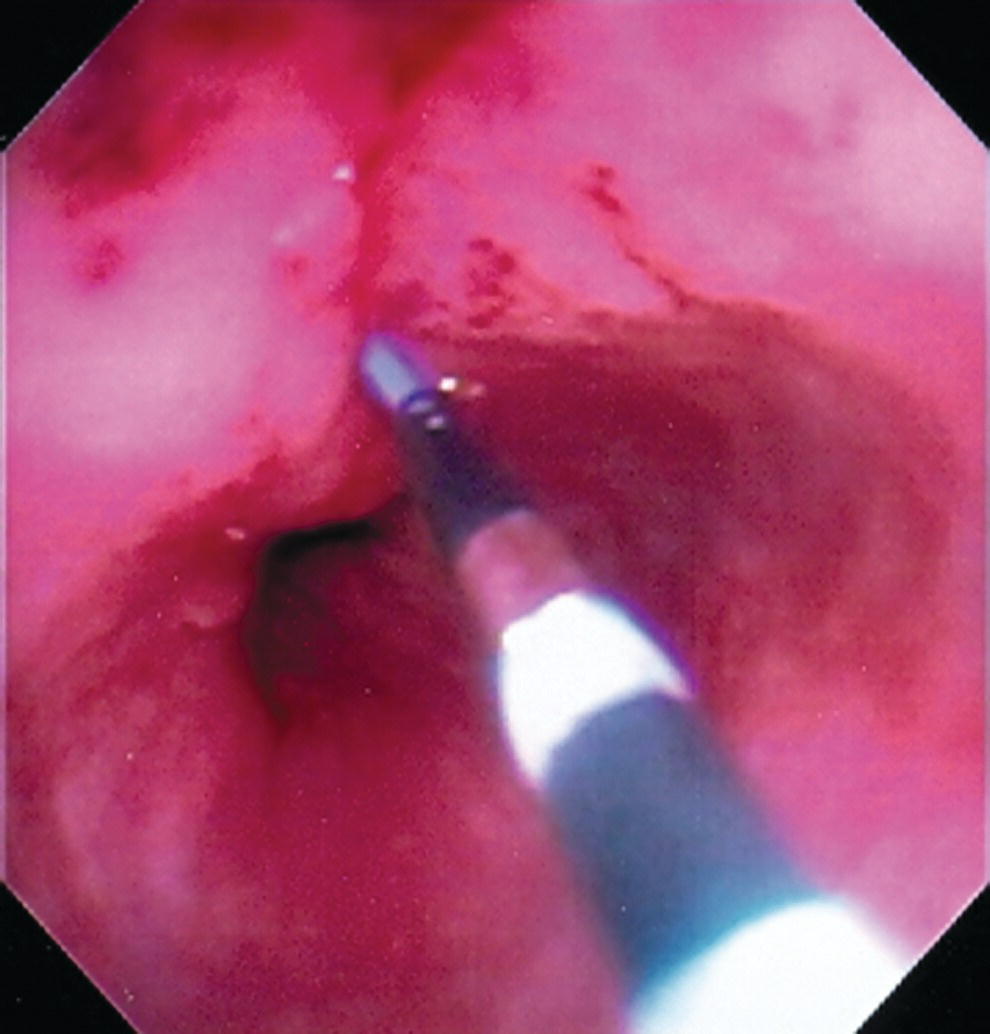

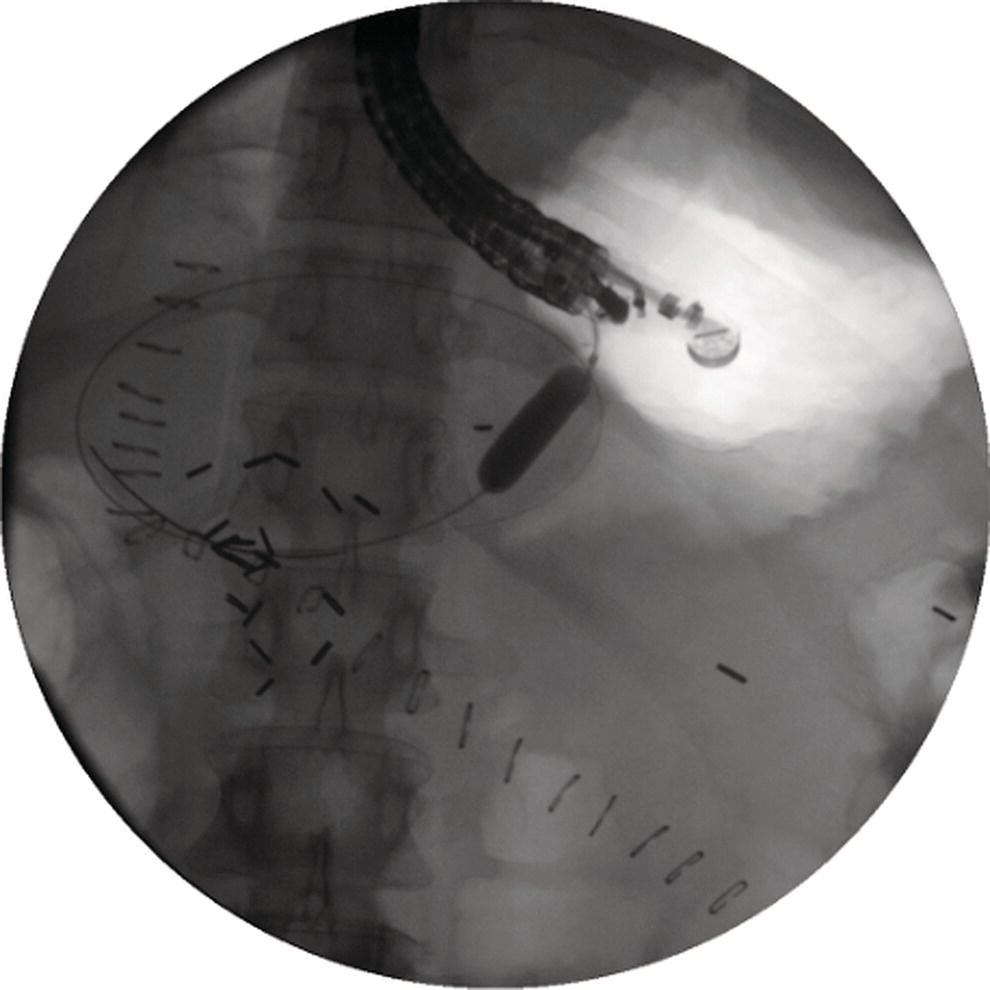

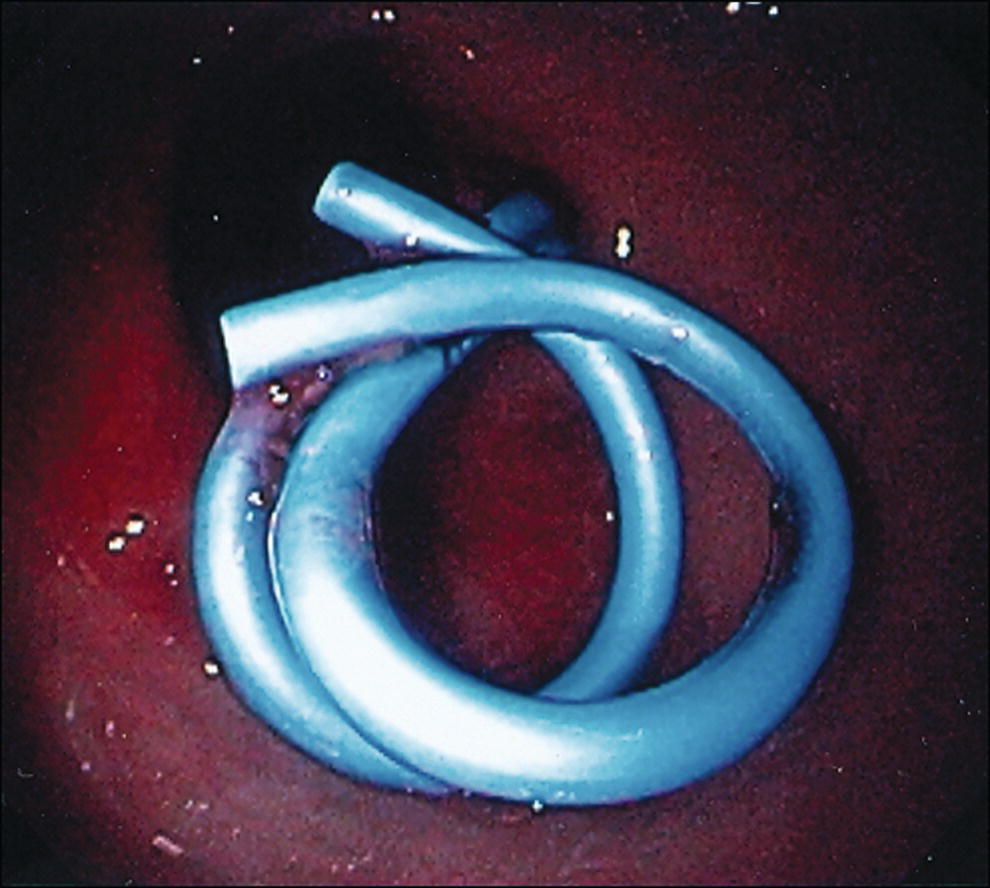

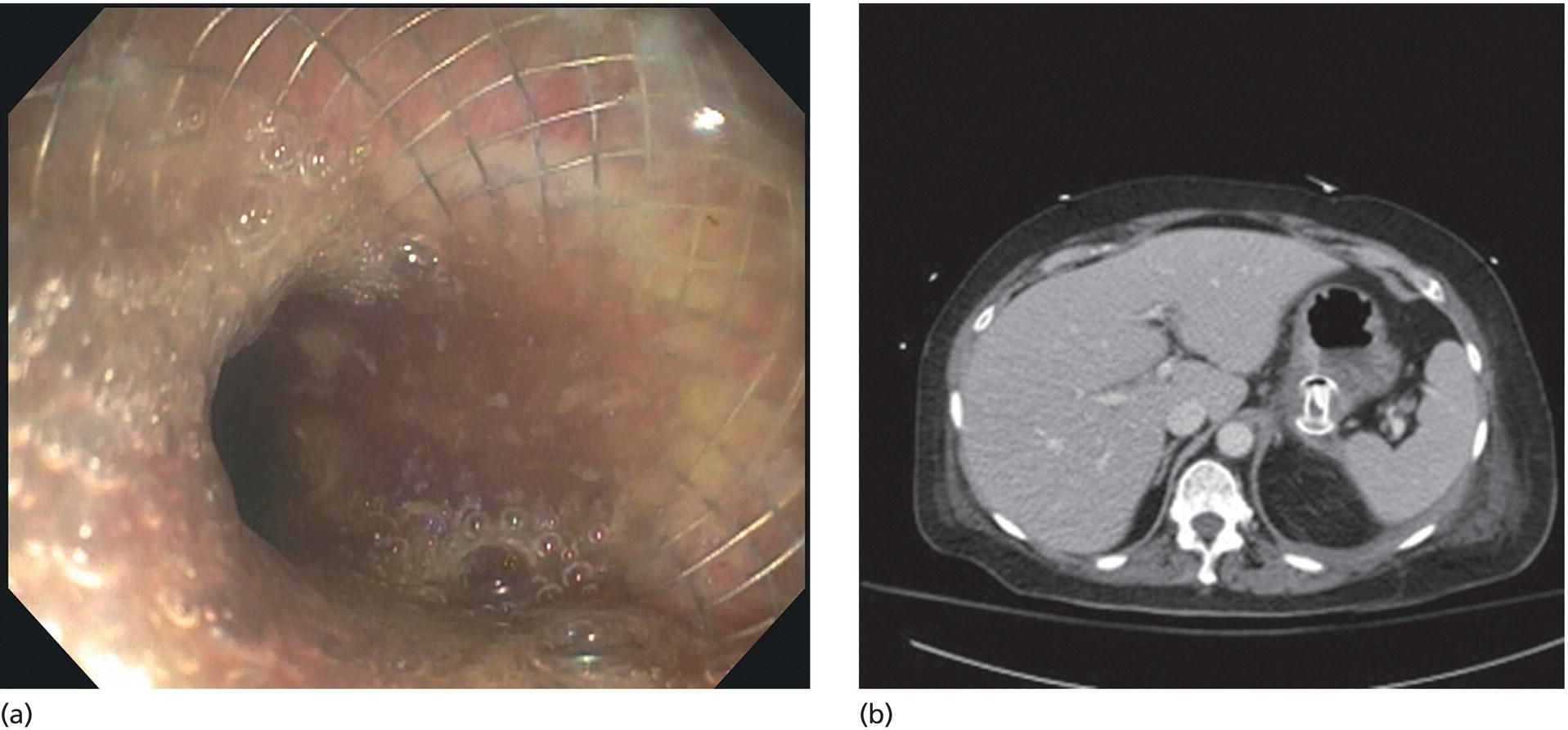

Shyam Varadarajulu1 and Vinay Dhir2 1 University of Alabama at Birmingham Medical Center, Birmingham, AL, USA 2 Institute of Advanced Endoscopy, Mumbai, India Pseudocysts (PCs) are fluid‐filled cavities surrounded by a non‐epithelial wall composed of inflammatory material. Drainage is required for large PCs that are persistent and symptomatic. Historically, PCs that produce a luminal compression on the stomach or duodenal wall are treated endoscopically by transmural drainage and those not causing a luminal compression by surgery or percutaneous techniques. Accumulating evidence over the past decade suggests that endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a safe and effective modality for drainage of PCs, irrespective of the presence or absence of a luminal compression. Unlike conventional transmural drainage, which is a relatively “blind” technique, EUS guidance enables the puncture of a PC under real‐time imaging thereby minimizing the potential for complications such as bleeding and perforation. Also, unlike percutaneous techniques, the procedure does not predispose to fistula formation or restrict patient mobility. Compared to surgery, EUS‐guided drainage is less invasive, less costly, and is associated with shorter length of hospital stay. The majority of the PCs larger than 4 cm in size and located adjacent to the gastric or duodenal wall are suitable for EUS‐guided drainage. Pseudocysts located in the tail region of the pancreas do not cause a luminal compression and may require puncture from unusual locations such as the distal esophagus. Although hitherto considered a relative contraindication, multiple large PCs can be accessed individually and drained successfully under EUS guidance when located close to the gastrointestinal (GI) lumen. Cysts smaller than 4 cm in size are not suitable for stent placement. If treatment is required in such cases, complete cyst aspiration under EUS guidance can be undertaken in one session. Alternatively, if the PC communicates with the main pancreatic duct, transpapillary stenting may be appropriate. Multiseptated cysts in general do not respond well to endotherapy as the non‐evacuated portions of the cyst tend to persist and suboptimal drainage predisposes to infection. Also, the presence of large amounts of necrotic debris warrants endoscopic necrosectomy or surgery. Transluminal stenting per se is inadequate therapy for necrotic fluid collections. A curvilinear array echoendoscope with a channel diameter of 3.7 mm or more is needed for stent depolyments. A 19‐gauge endoscopic ultrasound‐guided fine needle aspiration (EUS‐FNA) needle is required for passing a 0.035‐inch guidewire into the PC. Pseudocyst puncture can also be performed with a needle knife catheter, or with a one‐step needle wire device (available in Europe), or a cystotome. Over‐the‐wire balloon catheters are required for dilation of the transmural tract and double pigtail plastic stents for facilitating drainage of cyst contents. Nasocystic catheters may be required for continuous irrigation of the abscess cavity or necrotic contents. It is important to perform the procedures in a room equipped with fluoroscopy to monitor guidewire exchange and stent deployment. More recently, fully covered lumen‐apposing metal stents (LAMS) have become available for performing single‐step drainage procedures. These stents are incorporated in both a cautery and non‐cautery‐enhanced delivery platform and are available in diameters that range from 8 to 20 mm. The wide lumen of the stent facilitates quick drainage of cyst contents and the bilateral flanges at both ends minimize the risk of stent migration. A careful evaluation of the PC should be undertaken prior to puncture. The size, location, and number (single or multiple) of PCs should be determined. Most PCs are unilocular with predominantly clear contents and well‐defined walls (Figure 33.1). Multilocular cysts and those with mucinous contents or thick nodular walls need to be aspirated to rule out a neoplastic process (Figure 33.2). Also, a thorough survey of the pancreatic gland must be undertaken prior to drainage as a proximal tumor can cause a reactive PC. Some PCs located in the distal body or tail of the pancreas may cause splenic vein thrombosis and collaterals may be present between the cyst and gastric wall (Figure 33.3). In such cases, a puncture site should be chosen after excluding the presence of intervening vasculature (Figure 33.4). It is important that the PC is located within 1–2 cm of the GI lumen to avoid perforation or stent migration. Figure 33.1 A large unilocular pseudocyst with clear contents as visualized under EUS guidance. Figure 33.2 Two pseudocysts are seen at EUS: the promixal lesion on FNA analysis was a mucinous neoplasm and the distal lesion a reactive pseudocyst. Figure 33.3 Presence of intervening vasculature between the EUS transducer and the pseudocyts. Figure 33.4 Endoscopic ultrasound guidance enables access to the pseudocyst by providing an appropriate window in a patient with gastric varices. Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended prior to puncture of any cystic lesions. Pseudocyst puncture can be done with a 19‐gauge needle (Video 33.1) without the need for cautery (Figure 33.5). Alternatively, cautery‐assisted cyst puncture can be performed with help of a needle knife catheter or the Giovannini one‐step needle wire device. Puncture should preferably be done at a site where the echoendoscope is relatively straight. An angulated echoendoscope may cause resistance to passage of accessories and stents. As angulation is sometimes unavoidable when accessing a PC from the fundus of the stomach, we prefer not to use electrocautery in such situations as it may result in tangential catheter passage and perforation. The use of fluoroscopy aids in maintaining a straight position of the tip of the echoendoscope (Figure 33.6). Figure 33.5 Pseudocyst accessed with a 19‐gauge FNA needle. Figure 33.6 (a) Acute angulation encountered when the echoendoscope is located in the gastric fundus. (b) The tip of the echoendoscope is subsequently straightened with aid of fluoroscopy to facilitate passage of accessories. Once the needle is seen in the PC, fluid should be aspirated for analysis (Gram stain, culture, chemistry, or tumor marker studies). A 0.035‐inch guidewire is then coiled within the PC (Figure 33.7). The tract can then be dilated sequentially using a 5‐French (Fr) endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) catheter (Figure 33.8), Soehendra biliary dilator, 5.5‐Fr inner catheter of the Giovannini one‐step system, or the inner catheter of the cystotome. It is important to keep the guidewire taut as otherwise there may be resistance to passage of dilators. Subsequent dilation is then undertaken using an 8–15 mm over‐the‐wire balloon dilator (Figure 33.9). Large‐diameter balloons can be used when the cyst contents are turbid to facilitate better drainage. When using large‐diameter balloons it is important to ascertain that there is proper effacement between the PC and the GI lumen so as to avoid perforation. Figure 33.7 A 0.035‐inch guidewire is coiled within the pseudocyst under fluoroscopic guidance. Figure 33.8 The transmural tract is dilated using a 5‐Fr endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) cannula. Depending on the fluid consistency, a 7 or 10‐Fr double pigtail stent is deployed after transmural tract dilation (Figure 33.10). It is preferable to place more than one stent in large cysts. Multiple wires can be placed at one time if 7‐Fr stents are being deployed. Multiple wires should not be placed when 10‐Fr stents are deployed due to the small diameter of the echoendoscope channel. In such cases, it is better to cannulate again for subsequent deployment of individual 10‐Fr stents. During stent deployment, it is vital to keep the tip of the echoendoscope straight to avoid resistance. Sometimes, the thick viscous fluid from the PC can clog the biopsy channel and create friction during stent passage. This can be minimized by spraying PAM® (a cooking lubricant) through the biopsy channel prior to stent passage. Pseudocysts with large amounts of debris may require placement of a nasocystic drainage catheter (in addition to stents) to facilitate continuous irrigation and evacuation of cyst contents over a few days. Figure 33.9 The transmural tract is subsequently dilated using an 8 mm over‐the‐wire biliary balloon dilator. Figure 33.10 Multiple 7‐Fr transmural stents are deployed (fluoroscopy view) to facilitate drainage of pseudocyst contents. Figure 33.11 (a) Endoscopic view of the proximal flange of the LAMS in the stomach lumen with drainage of cyst contents. (b) CT of the abdomen demonstrating the LAMS placed for drainage of pseudocyst. The pseudocyst is punctured under endosonographic guidance using a 19G FNA needle, followed by insertion of a 0.025‐ or 0.035‐inch guidewire through the needle, which is looped inside the cavity. The transmural tract is then sequentially dilated using first an ERCP cannula, needle knife catheter or a cystotome, followed by a 4–6 mm dilating balloon. Excessive dilation must be avoided in order to prevent stent migration. LAMS on a delivery system is then inserted over the guidewire into the pseudocyst cavity. The distal flange is first deployed under endosonographic guidance, followed by deployment of the proximal flange under either endosonographic or endoscopic view. The pseudocyst is directly punctured (without the need for a guidewire) using the electrocautery‐enhanced tip of the stent delivery system under endosonographic guidance. The delivery system is then advanced into the PC and the distal flange is deployed first under endosonographic guidance, followed by deployment of the proximal flange under endosonographic or endoscopic view (Figure 33.11 and Video 33.2). After the procedure, the patient is observed for signs of infection, bleeding, or pancreatitis. The majority of patients can resume oral intake the same day. Antibiotics are continued for 48 hours. A follow‐up computed tomography (CT) is usually undertaken in six to eight weeks (for plastic stents) or in three to four weeks (for LAMS) to assess response to therapy. However, following the procedure, if a patient develops persistent pain, unremitting fever, chills or leukocytosis, a CT scan should be obtained to rule out procedural complications.

33

How to do Pancreatic Pseudocyst Drainage

Introduction

Patient selection

Requisite instruments and accessories

Assessment of the pseudocyst by EUS prior to drainage

Technique for placement of plastic endoprosthesis

Pseudocyst puncture

Transmural tract dilation

Stent deployment

Technique for lumen‐apposing metal stent placement

Non‐electrocautery‐enhanced delivery system

Electrocautery‐enhanced delivery system

Post‐procedure follow‐up

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree