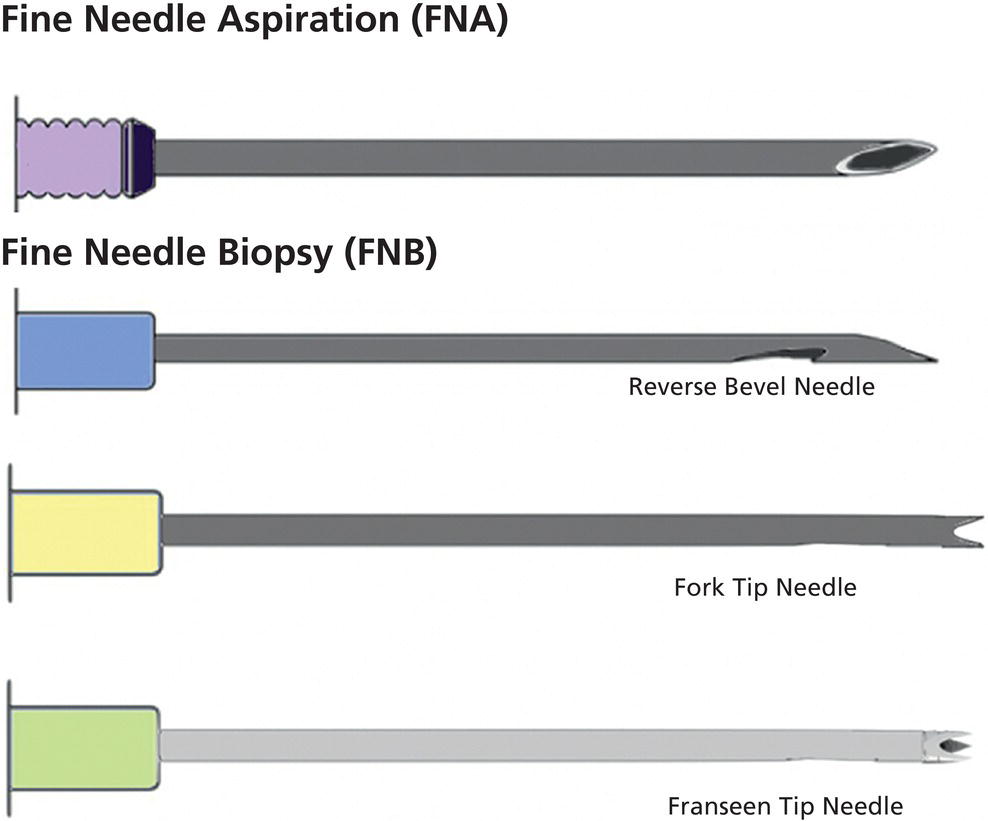

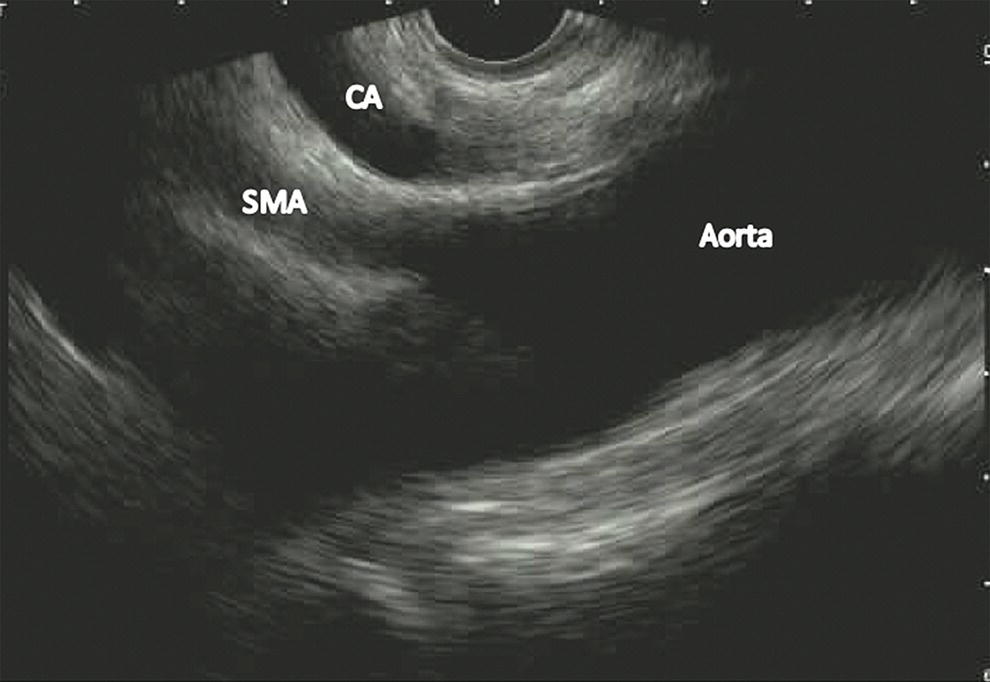

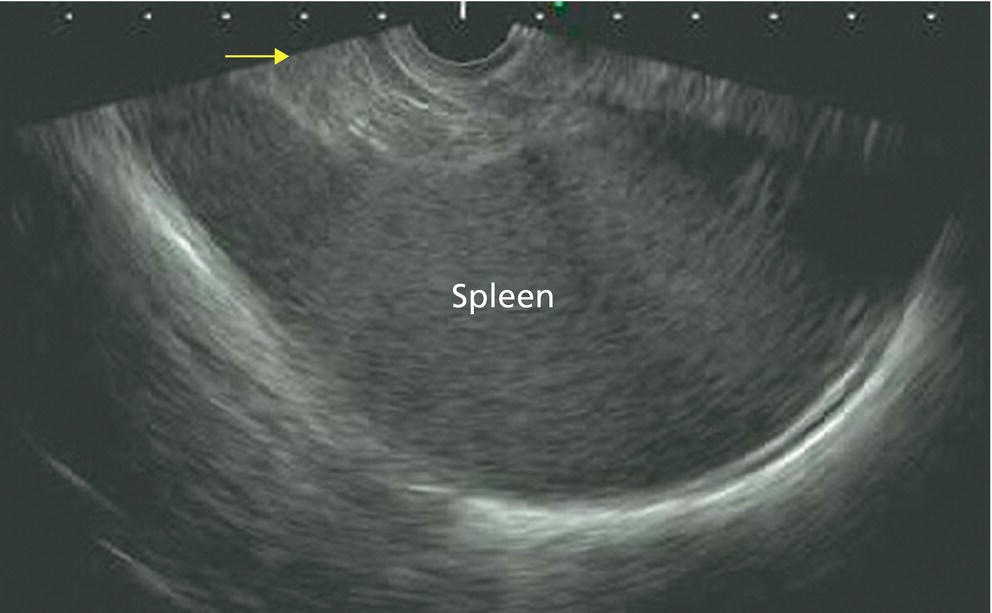

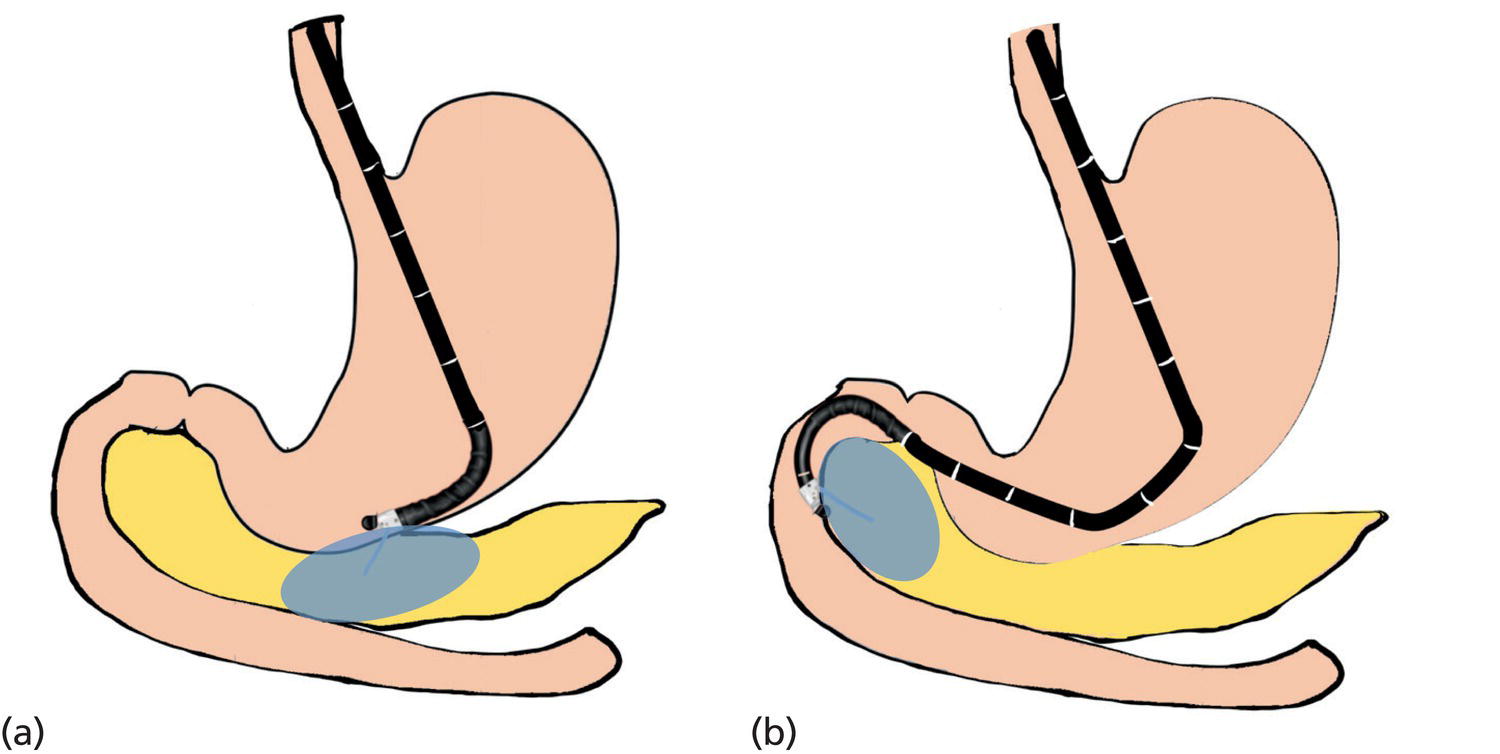

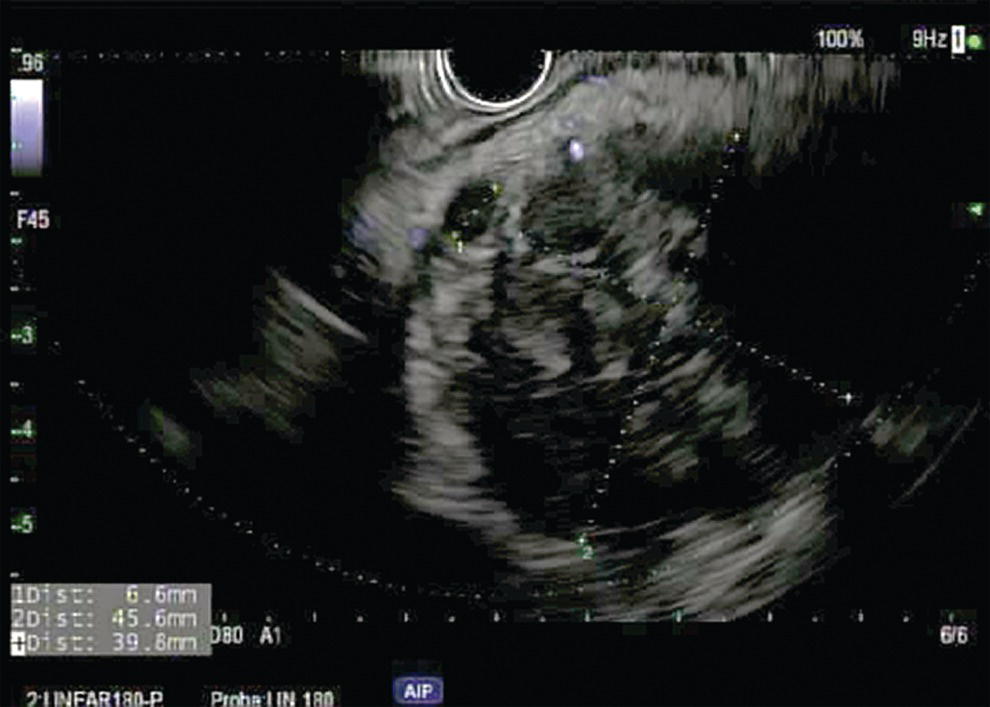

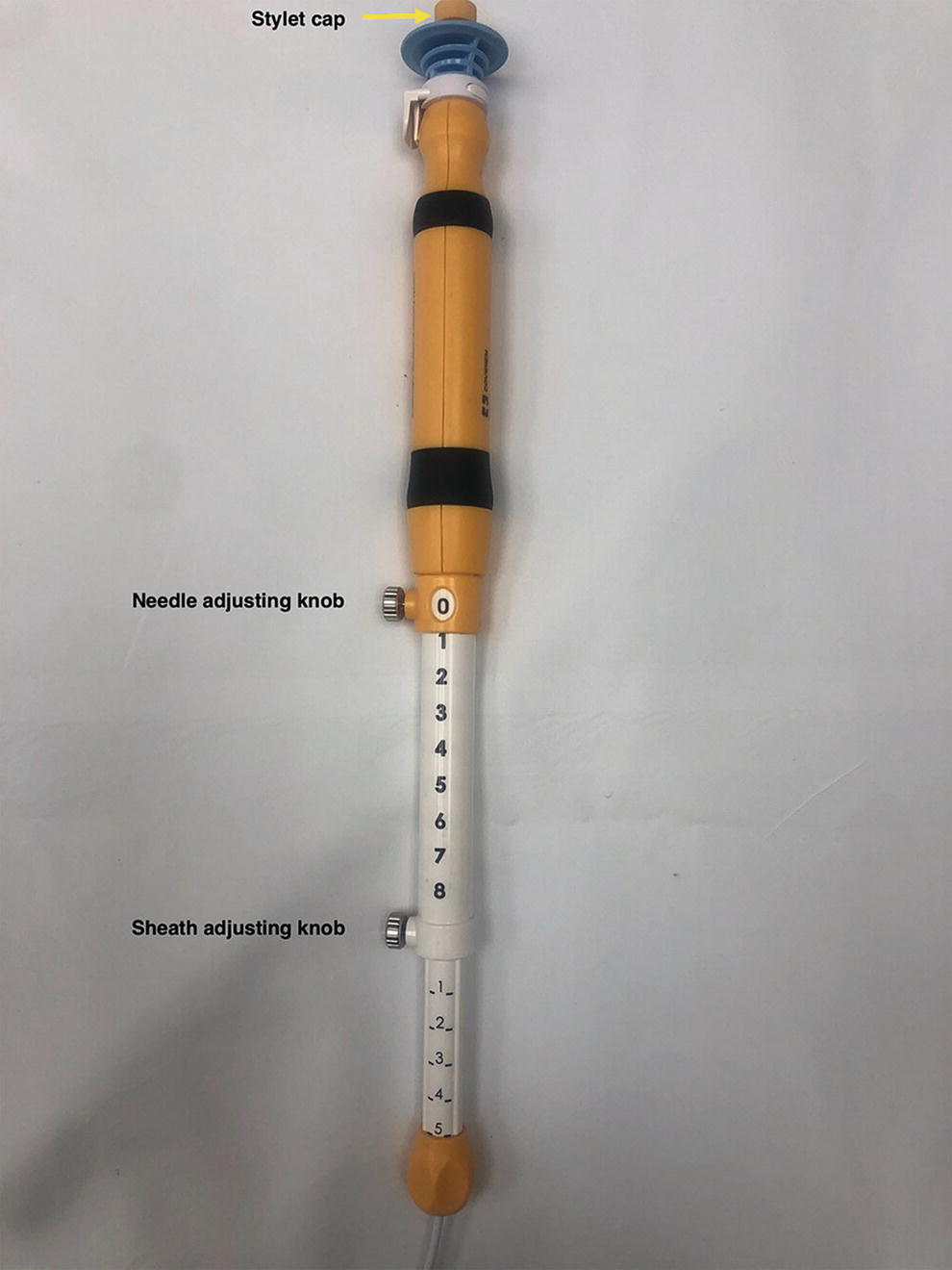

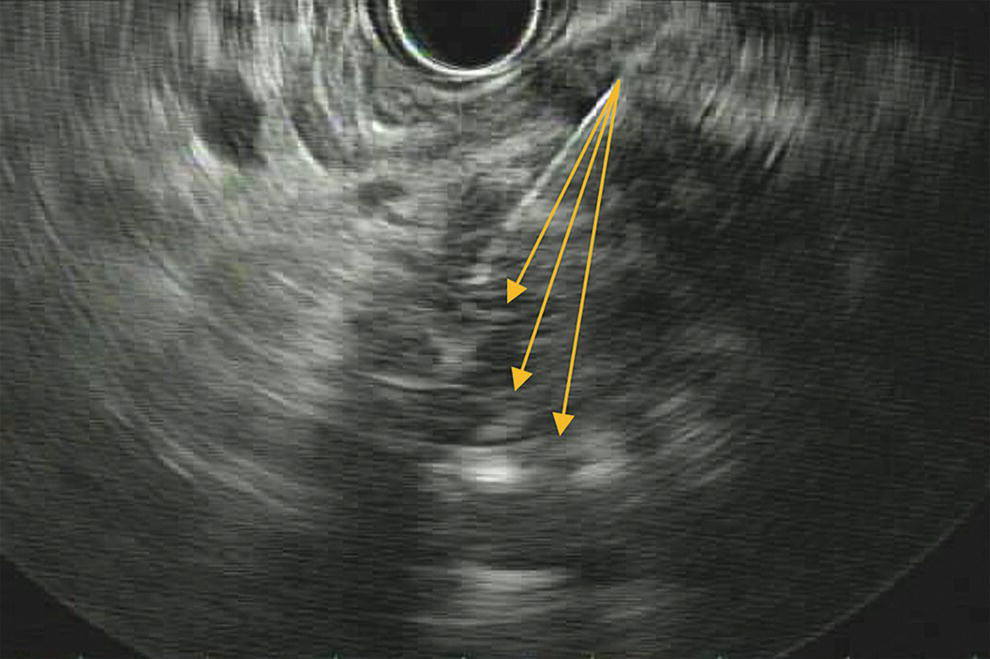

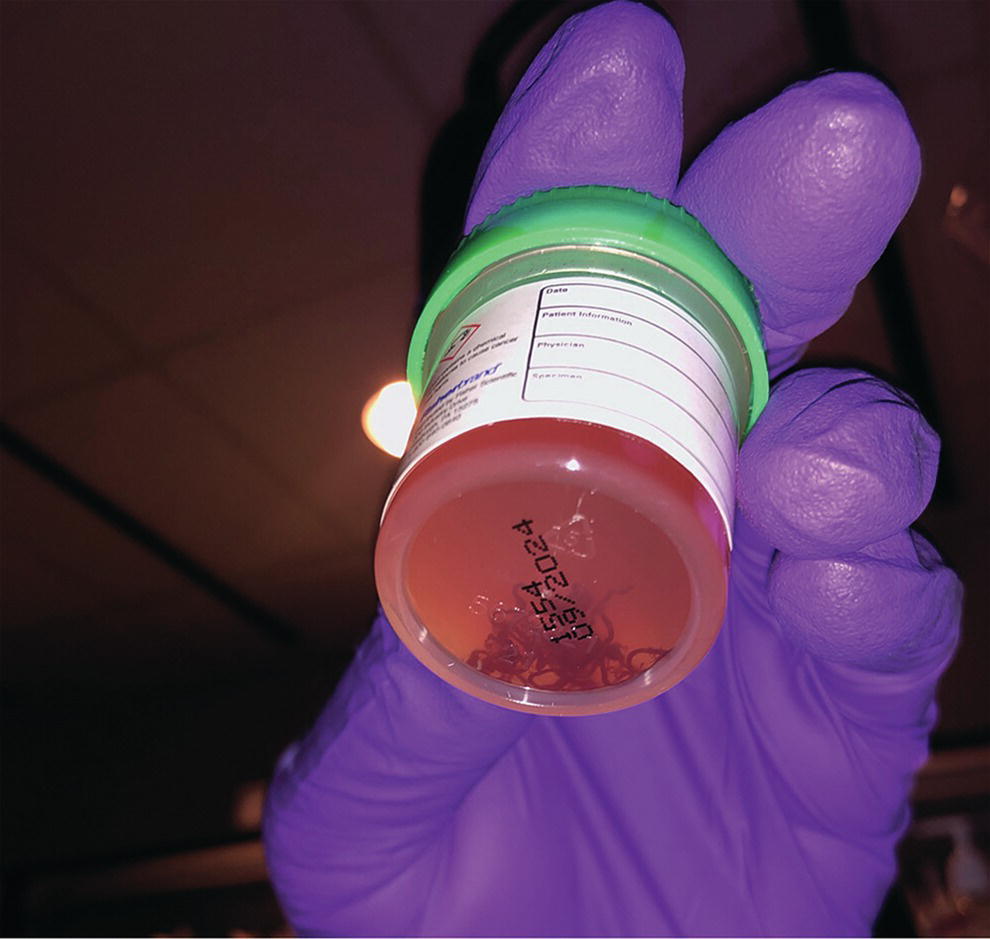

Ahmad Najdat Bazarbashi and Linda S. Lee Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA The differential diagnosis for pancreatic masses is broad, ranging from benign to malignant lesions such as autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Therefore, many pancreatic masses seen on radiology imaging require biopsy, and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has emerged as the premier diagnostic modality for safely acquiring tissue. EUS provides real‐time information about details of the mass, including its size, shape, border, content, echogenicity, and impact on surrounding structures, and assesses for locoregional spread. EUS‐guided tissue sampling occurs via fine needle aspiration (FNA) or fine needle biopsy (FNB). FNA uses a hollow needle and provides cellular material for cytology, while FNB needles provide core tissue samples for architectural analysis (Figure 54.1). The first FNB needle called TruCut needle (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN) was 19G. Now core biopsy needles are available as 19G, 22G, and 25G with different tip designs, although whether one configuration is superior remains to be determined. Fork‐tip FNB needles may improve diagnostic yield, but further studies are needed. Compared to FNA, FNB increases histological yield and sufficient tissue for tumor genotyping with fewer passes needed for diagnosis, eliminates need for rapid on‐site evaluation (ROSE), and may improve diagnostic accuracy in solid pancreatic masses. When lymphoma, sarcoidosis, or autoimmune pancreatitis are in the differential diagnosis, core biopsies should be obtained. Reassuringly, both FNA and FNB have low risk of complications, including 1–2% risk of pancreatitis. Before EUS, history and physical examination should focus on symptoms related to the mass and risk factors for a pancreatic mass including history of autoimmune diseases, smoking and alcohol intake, and family history of pancreatic cancer. Platelet count and international normalized ratio (INR) should be obtained if there is concern for high risk of bleeding. Anticoagulation should be held after discussion with the prescribing clinician. Endosonographers must carefully review cross‐sectional imaging to understand the patient’s anatomy, location of the mass, presence of potential metastatic disease and to anticipate potential difficulties in finding and sampling the mass. Informed consent from the patient should review the nature of the procedure, risks, benefits and alternatives. Risks to highlight include bleeding, abdominal pain, pancreatitis, and perforation. Patients should be informed of potential issues including, for example, possible difficulties in accessing and obtaining biopsies from uncinate process masses. Anesthesia rather than intravenous conscious sedation may be associated with improved diagnostic yield. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) often precedes EUS to ensure there are no anatomical abnormalities that may interfere with advancing the echoendoscope or visualizing the pancreas and surrounding structures and not infrequently reveals unexpected findings. Once EGD is completed, the echoendoscope is passed into the stomach and duodenum. Linear echoendoscope should be used rather than radial echoendoscope since it allows tissue acquisition. EUS examination begins with evaluating for potential locoregional spread of disease to areas such as the liver or celiac region (Figure 54.2). FNA/FNB of lymphadenopathy and metastases to surrounding structures should be performed to confirm metastatic disease. From the stomach, the pancreas can be located by rotating 180 degrees from the thickest portion of the left lobe of the liver or by following the superior mesenteric artery to the body of the pancreas. The genu, body and tail of pancreas (Figure 54.3) can be evaluated from the transgastric station, while the head and uncinate process are usually seen from the transduodenal station (Figure 54.4). Figure 54.1 Fine needle aspiration versus fine needle biopsy needles. Figure 54.2 EUS of aorta, celiac artery (CA) and superior mesenteric artery (SMA). Source: Frank G. Gress. Pancreatic masses usually appear hypoechoic and may be homogeneous or heterogeneous with regular or irregular borders (Figure 54.5). Once the location of the mass is confirmed, it is ideally placed near the 6 o’clock position as close to the tip of the echoendoscope as possible using the large dial. Doppler imaging ensures blood vessels are not in the path of needle insertion (Figure 54.6). For FNB, 22G and 25G needles are often used while 19G needles are usually not necessary and are more difficult to advance forward in the duodenum. FNB needles made of nitinol (Acquire 19G, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA and SharkCore 19G, Medtronic, Sunnyvale, CA) may be more flexible and easier to use in these torqued angulated positions. After removing the biopsy cap, the needle device is advanced down the accessory channel and locked onto the Luer lock at the accessory channel port. The large and small dials on the echoendoscope should be locked to ensure that slight movements or deviations during needle advancement are minimized. The position of the sheath can be adjusted using the bottom slider on the needle handle (Figure 54.7), which allows use of the various needles with the different brands of echoendoscopes. Once the sheath is visible, the sheath adjusting knob should be locked, and for some FNB needles the stylet is pulled back slightly to expose the needle. How far to advance the needle can be estimated by measuring the distance from the tip of the echoendoscope to the mass, and the adjustable needle knob near the top of the needle handle (Figure 54.7) should be locked in position accordingly to prevent accidentally advancing the needle too far. Then the needle is slowly advanced out of the sheath until it nears the gastric or duodenal wall. If the needle does not move easily, it should not be forced out as this could damage the echoendoscope; instead, reposition the echoendoscope and unlock the dials before trying to advance the needle. After using Doppler to ensure lack of blood vessels in the path of the needle and the elevator to adjust the angle of needle entry, the needle is advanced with a rapid, strong thrust to penetrate through the posterior gastric or duodenal wall into the pancreatic mass (Figure 54.8). The stylet is pushed back in to expel any gastric or duodenal wall tissue that may have been captured; however, whether a stylet is used for subsequent passes does not affect diagnostic yield. It serves to stiffen the needle and may help the assistant expel tissue from the needle. Application of some type of suction may increase diagnostic yield. Options include the stylet slow‐pull technique where the assistant slowly and continuously pulls back on the stylet as the endosonographer moves the needle back and forth within the mass, vacuum syringe with a 10‐ml syringe attached to the top of the needle handle, or wet suction where the needle is filled with saline before attaching the vacuum syringe. The latter two suction techniques require complete removal of the stylet first. If specimens appear bloody, no suction can be used. Typically, the needle is moved back and forth within the mass about 10–15 times although fewer movements may be needed with FNB needles. The needle trajectory should be adjusted by using the elevator and/or large dial to “fan” the needle throughout the mass to increase diagnostic yield (Figure 54.9). The needle tip should always be visualized. Figure 54.3 Tail of pancreas (yellow arrow) and spleen. Source: Frank G. Gress. Figure 54.4 EUS‐guided (a) transgastric and (b) transduodenal pancreatic tissue acquisition. Figure 54.5 Large heterogeneous well‐defined pancreatic head mass. Source: Frank G. Gress. Once FNB is complete, the suction stopcock should be turned off with or without removing the syringe before the needle is withdrawn to avoid contaminating the collected specimen. The fully withdrawn needle locked in position is then completely removed from the echoendoscope. The assistant expels the tissue from the needle into a collection container using the stylet or air from the vacuum syringe. Macroscopic evaluation of the tissue to confirm presence of visible pale cores of tissue is associated with histological diagnosis (Figure 54.10). When FNB is compared with FNA plus ROSE, diagnostic yield is comparable. If ROSE is not used, two to three separate FNB passes are recommended. A different needle should be used if moving from biopsying the pancreatic mass to potential metastatic lesions in order to avoid contaminating benign tissue. Antibiotics are not routinely given for EUS‐FNA/FNB of solid pancreatic lesions. Figure 54.6 Vessels (yellow arrow) in path of FNB needle to pancreatic mass. Source: Frank G. Gress. EUS‐guided FNA/FNB is the premier method for tissue acquisition of the pancreas. FNB is superior to FNA, with increased yield of histological cores requiring fewer passes for diagnosis. However, careful attention to proper technique is important to ensure optimal and safe biopsy. This begins with detailed review of radiological imaging and includes thoughtfulness about needle selection, with smaller gauge needles favored for transduodenal approaches, use of suction, and macroscopic assessment of acquired tissue during the procedure. During biopsy, Doppler should be used to avoid blood vessels, the mass positioned as close to the transducer as possible, and fanning employed to increase diagnostic yield. Figure 54.7 Fine needle biopsy handle. Source: Frank G. Gress. Figure 54.8 EUS‐FNB of pancreatic mass. Tip of FNB needle seen within mass (yellow arrow). Source: Frank G. Gress. Figure 54.9 Fanning to increase tissue acquisition. Source: Frank G. Gress. Figure 54.10 Macroscopically visible strands of fine needle biopsy tissue. Source: Frank G. Gress.

54

How to Perform Pancreatic Mass Fine Needle Biopsy

Introduction

Technique (Video 54.1)

Summary

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree