Hydrocephalus and Shunt

Monica D. Watkins

Hydrocephalus may be life threatening and require emergency surgical treatment. It is subdivided into “communicating” hydrocephalus which is characterized by dilation of the entire ventricular system due to impaired cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) reabsorption versus “non-communicating” hydrocephalus which is due to a focal obstruction of a ventricle, foramina, or aqueduct.

In the pediatric population, most cases of hydrocephalus occur due to communicating hydrocephalus following intraventricular hemorrhage (˜35% of all cases) or an episode of meningitis. Noncommunicating hydrocephalus due to aqueductal stenosis or brain mass is less common.

Causes of hydrocephalus in the adult population include communicating hydrocephalus following subarachnoid hemorrhage or meningitis. Normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) is a form of communicating hydrocephalus occurring in the elderly population. The diagnosis is suggested when the ventricular system is dilated out of proportion to the amount of sulcal dilatation due to atrophy. The patients tend to have clinical symptoms of dementia, gait ataxia, and urinary incontinence (the three W’s: wacky, wobbly, and wet). Noncommunicating hydrocephalus due to tumor is less common.

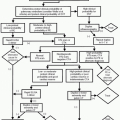

Patients may become symptomatic from hydrocephalus due to increased intracranial pressure (ICP).

In most cases of hydrocephalus, treatment requires placement of a shunt. One end of the catheter is placed in the ventricular system and the distal end is placed either in the peritoneal cavity (ventriculoperitoneal shunt) or the right atrium (ventriculoatrial shunt). The ventriculoperitoneal shunt is by far the most common type and is the treatment of choice for a pediatric patient. Typically, an extended tube length of 120 cm is placed within the peritoneal cavity in infants to allow for growth of the patient.

In the case of NPH, patients may receive a trial of repeated lumbar tap and if symptoms do improve, a ventricular peritoneal shunt may be placed.

Shunt failure resulting in increasing hydrocephalus has been reported extensively in the pediatric population, where between 17 and 40% of ventriculoperitoneal shunts will fail within the first year.

There are many causes of shunt failure of which the most common is obstruction of tubing due to blood, proteinacious material, or even talc from surgical gloves. Obstruction is more common within the proximal end than the distal end. Mechanical failure due to broken or kinked tubing or valve malfunction is also common.

A rare cause of distal obstruction (6-8% of shunt failures) is the formation of abdominal pseudocyst in which a collection of CSF is surrounded by nonepithelial tissue and is usually associated with infection. Other uncommon complications include migration of the catheter out of the ventricular system or distal tip out of the peritoneal cavity. There are a few reported cases of the distal shunt catheter becoming entangled in the bowel and

resulting in necrosis. A patient can be overshunted leading to “intracranial hypotension syndrome.” Instead of enlarging ventricles, patients may present with headache, slitlike ventricle, and possibly subdural hematomas. This is rare as many shunt systems have antisiphoning devices to prevent overshunting.

resulting in necrosis. A patient can be overshunted leading to “intracranial hypotension syndrome.” Instead of enlarging ventricles, patients may present with headache, slitlike ventricle, and possibly subdural hematomas. This is rare as many shunt systems have antisiphoning devices to prevent overshunting.

Symptoms are mainly due to worsening hydrocephalus with resulting increased ICP.

Mild increase in ICP

Headache, nausea, vomiting, ataxia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree