10 Hyperlucent Lung The roentgenographic density of the lungs is determined by the absorption of roentgen rays by gas, blood, and tissue. The major blood vessels have a density of 1.0 g/ml, whereas the density of lung parenchyma at total capacity is only 0.08 g/ml. This allows visualization of blood vessels in the lungs without using contrast medium. The density of lung parenchyma increases with the increasing amount of capillary blood and interstitial tissue or fluid. The increase in the amount of contained gas decreases the lung density. A decrease of lung density manifests as increased darkening on the chest radiograph. The sensitivity of the assessment of bilateral changes in lung density with roentgenograms is limited due to technical variables, variations in the amount of extrathoracic soft tissue, and observer error. CT is able to detect bilateral pulmonary hyperlucency earlier, when plain films are still apparently normal. An apparent bilateral decrease of pulmonary density may be caused by three factors or combinations thereof: (1) reduction of the caliber of peripheral pulmonary vessels; (2) reduction of the size of pulmonary hila; and (3) generalized pulmonary overinflation. Four combinations of these changes are possible: 1. Small peripheral vessels, no overinflation; small hila. This combination is indicative of a reduction in pulmonary blood flow and is pathognomonic of usually cyanotic congenital cardiac anomalies with a right to left shunt (tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia, persistent truncus arteriosus Type IV, Ebstein’s anomaly) or of isolated pulmonic stenosis without poststenotic dilatation. 2. Small peripheral vessels; no overinflation; enlarged hilar pulmonary arteries. This combination results from various causes of pulmonary artery hypertension (pulmonary artery stenosis, widespread embolic disease to small arteries, pulmonary arteritis, primary pulmonary hypertension, etc.). 3. General pulmonary overinflation; small peripheral vessels; normal or enlarged hilar pulmonary arteries. This combination is pathognomonic of bilateral pulmonary hyperinflation due to an airway disease such as emphysema. 4. Generalized overinflation of lungs; vascular markings throughout the lungs of normal caliber; normal hilar shadows. This combination is pathognomonic of bilateral acute airway disease such as an asthmatic attack or bronchiolitis. The diseases that manifest as combinations 1 and 2 are presented in Chapter 1 and only airway diseases appearing as diffuse, bilaterally hyperlucent lungs, e.g., a general excess of air in the lungs, are included in Table 10.1. Unilateral hyperlucency of a lung is easier to perceive than a bilaterally increased radiolucency. However, asymmetry of the roentgenographic density of the two lungs may be due to factors unrelated to lung disease. If the patient is rotated, the density of the lung on which the spine is superimposed will be uniformly greater than the density of the other lung. A similar effect may be produced by scoliosis or by incorrect centering of the roentgen beam. Other nonpulmonary causes of asymmetry of the roentgenographic density are the asymmetry of soft tissues surrounding the chest (e.g., caused by a mastectomy, unilateral hypoplasia, or as absence of thoracic musculature) or a grossly asymmetric thoracic cage. It may also occasionally be difficult to decide whether the side of lower or higher density is abnormal in the case of asymmetric density. Diffuse unilateral alveolar consolidation (e.g., pneumonia), unilateral pulmonary edema, or the effect of pleural effusion on supine film should be easy to exclude as causes of asymmetric density by using the general diagnostic signs of parenchymal disease (see Chapter 20) or pleural disease (Chapter 18). Localized pulmonary hyperlucency may involve the whole lung, a lobe, or a segment. A pulmonary air cyst (bulla or bleb) must be one to a few centimeters in diameter in order to be visible, since the change in density and vasculature can only be compared with the remainder of the lung at that size. The diagnostic evaluation of localized pulmonary hyperlucency is based on the same variables as is generalized hyperlucency: (1) the amount of air in the involved area, (2) the presence and caliber of blood vessels in the hyperlucent area, and (3) possible changes in the central pulmonary arteries or hilar nodes. The localized decrease of blood flow in the hyperlucent area may cause a compensatory increase of flow in the remaining or contralateral lung. Hilar changes in localized pulmonary hyperlucency may be insignificant or absent in the case of small hyperlucent lesions. When the whole lung is involved (unilateral hyperlucent lung) or when there is compensatory ipsilateral hyperinflation due to lobar atelectasis, the altered caliber or course of the major pulmonary arterial branches or possible hilar adenopathy may provide important diagnostic information. A fourth important diagnostic variable in localized hyperlucency, the presence or absence of air trapping, is obtained by comparing inspiratory and expiratory films. Lobar air trapping is virtually diagnostic of obstructive emphysema (e.g., foreign body or tumor). Diseases characterized by a unilateral hyperlucent lung or by localized pulmonary hyperlucency and their differential diagnostic features are presented in Table 10.2.

Disease | Radiographic Findings | Comments |

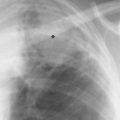

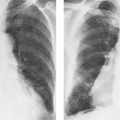

Chronic obstructive emphysema (Figs. 10.1 and 10.2) | 1 General signs of overinflation: hyperlucent lungs; low, flat, or concave diaphragm; increased post-eroanterior chest diameter; increased retrosternal space. 2 Limitation of diaphragmatic excursions to less than 2 cm, and air trapping evident by comparing inspiratory and expiratory films. 3 Rapid peripheral tapering of pulmonary vessels and their unequal distribution, often with the presence of bullae. Small heart. (Emphysema with decreased pulmonary markings). 4 Prominent pulmonary vessels of an irregular and indistinct contour and often with cor pulmonale. Bullae uncommon. (Emphysema with increased pulmonary markings). | Pattern 3 is common in panlobular emphysema (“pink puffer”) and pattern 4 in centrilobular emphysema (“blue bloater”). The “increased markings” emphysema (pattern 4) is often overlooked and regarded merely as chronic bronchitis or recurrent bronchopneumonitis, since signs of overinflation are less prominent. Signs of overinflation may be superimposed and partially obscured by left-sided heart failure. Usually associated with chronic bronchitis. In the absence of chronic bronchitis, emphysema may be associated with rare heritable connective tissue diseases (Marfan’s syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, cutis laxa) or with α1–antitrypsin deficiency and predominantly lower lobe emphysema. |

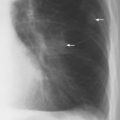

Primary bullous disease of the lung (vanishing lung) (Fig. 10.3) | Bullae (air-filled, thin-walled, sharply demarcated avascular spaces within the lung) more commonly occur in the upper lobes and may grow. There is hyperinflation (as in chronic obstructive emphysema), but no diffuse oligemia of the remaining pulmonary parenchyma. | Primary bullous disease of the lung involves males and is asymptomatic unless the remaining healthy lung parenchyma is severely compressed. Spontaneous pneumothorax from ruptured bullae is common. Bullae are a common feature of chronic obstructive emphysema, with which bullous disease can be fortuitously associated. |

Asthma (status asthmaticus, prolonged asthmatic attack) (Fig. 10.4) | Severe overinflation of lungs with air trapping. Lowered diaphragm, but it is still convex. The vascular markings throughout the lungs are of normal caliber. Tubular shadows or “tram lines” may represent edema or thickening of bronchial walls. | Between the episodes, the chest roentgenogram is often normal. Severe status asthmaticus and diffuse emphysema can be differentiated by the lack of pulmonary oligemia and the concave configuration of the upper surface of the diaphragm in the former. |

Acute bronchiolitis (Fig. 10.5) | Severe overinflation of the lungs may be the only finding. Often accentuated lung markings and small miliary nodules (reticulonodular pattern), particularly in lower zones. Local areas of atelectasis occur in 15%. | Usually a viral infection of small airways. Affects children below the age of three years and adults with a pre-existing chronic respiratory disease. Childhood bronchiolitis may cause unilateral or lobar emphysema (MacLeod’s syndrome) in later life through bronchiolitis obliterans, overdistention and emphysematous destruction. |

Diffuse infantile bronchopneumonia | Diffuse or patchy overinflation. Enlargement of peribronchial lymph nodes. Consolidation usually follows, eventually associated with patchy atelectasis. | This type of bilateral pneumonia is a common complication of whooping cough, measles, and influenza, but is rarely seen in bacterial pneumonia Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|