Fig. 13.1

Corpus luteal cyst. (a) Sagittal grayscale transabdominal ultrasound image of the pelvis demonstrates a large, cystic lesion (arrow) with relatively homogeneous internal echogenicity and posterior acoustic enhancement. (b) Ultrasound study demonstrates a hemorrhagic functional ovarian cyst containing a blood clot (arrowhead). There is surrounding hemorrhagic fluid (straight arrow) that is also seen in the adnexa. (c) Axial T2-weighted MR image of the pelvis shows a T2 hyperintense corpus luteal cyst in the left hemipelvis (arrow). Note the thin wall and lack of internal septations or nodularity

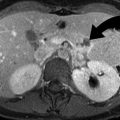

Fig. 13.2

Hemorrhagic ovarian cyst and appendicitis. (a) Contrast-enhanced axial CT image through the pelvis demonstrates an enlarged appendix with surrounded inflammatory fat stranding in the right lower quadrant (arrow). An oval, rim-enhancing ovarian cyst is identified to the right of the uterus (arrowhead), along with small amount of free fluid. (b) Axial contrast-enhanced, T1-weighted MR image with fat saturation obtained through the pelvis demonstrates a hyperenhancing, enlarged appendix with surrounding inflammatory changes in the adjacent mesenteric fat (arrow). The nonenhancing internal component of the hemorrhagic right ovarian cyst (arrowhead) is homogeneously T1 hyperintense, consistent with methemoglobin

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Tubo-Ovarian Abscess and Pyosalpinx

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is usually caused by bacterial infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae [4]. Infection begins in the vagina and spreads to the endometrium causing endometritis. The infection then extends into the fallopian tube. The resulting inflammatory changes, edema, and exudate result in obstruction of the fallopian tube and formation of a pyosalpinx [5]. The infection then extends out along the fimbria and enters the ovary (often via a ruptured corpus luteum), leading to tubo-ovarian abscess [6]. The disease can spread in the peritoneal space to involve various organs including the liver and right paracolic gutter (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome).

The symptoms are often nonspecific and may include fever, pelvic pain, cervical/adnexal tenderness (chandelier sign), vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, nausea, and vomiting. Up to 35 % of the patients with PID have no symptoms [7].

Imaging

Pelvic ultrasound is the modality of choice when PID is suspected, due to high sensitivity and specificity with relatively low cost. Because the symptoms of PID are nonspecific, CT is often the first study performed, especially when the differential diagnosis is wide and includes other suspected pathologies such as diverticulitis or appendicitis (Fig. 13.3a). Pelvic MRI also has high sensitivity and specificity for pelvic inflammatory disease; however, it is usually not considered a first-line imaging modality (Figs. 13.3b and 13.4) [4].

Fig. 13.3

Tubo-ovarian abscess. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced CT image through the pelvis shows a left adnexal lesion containing a peripherally enhancing tubo-ovarian abscess (arrowhead) with a small focus of nondependent air. The ovary and fallopian tube are not distinguishable as separate structures. (b) Coronal noncontrast T2-weighted MR image of the pelvis demonstrates a large T2 hyperintense right adnexal abscess with a thick peripheral capsule and an internal septation (arrow). A mildly dilated, serpiginous fallopian tube (arrowheads) with a thick wall is seen extending in to the abscess

Fig. 13.4

Pyosalpinx (a) Transvaginal ultrasound image demonstrates a dilated fallopian tube (arrowheads) located adjacent to the ovary (arrow). (b) Sagittal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image with fat saturation demonstrates a dilated fallopian tube (arrowhead) with incomplete internal septations and prominent contrast enhancement of the thickened tube wall

On ultrasound, the fallopian tubes often become distended with fluid in patients with PID. In acute disease, the fallopian tube walls measure 5 mm or thicker and demonstrate abundant color flow with reduced flow resistance on the Doppler images (resistive index near 0.5). As the fluid-filled fallopian tubes distend, they become tortuous and fold on themselves; these folds have the appearance of incomplete septa. The thickened tube wall, fluid-filled lumen, and thickened mucosal folds can produce the “cogwheel sign” [5]. In pyosalpinx, fluid-debris levels are often visualized in the distended tubes. If the ovary cannot be visualized separate from this inflammatory mass, then the diagnosis of a tubo-ovarian abscess should be suggested rather than pyosalpinx. In chronic tubal disease, the luminal distention increases, the tube wall becomes thin, and mucosal folds are much more spread out resulting in a “beads-on-a-string” sign when visualized in cross section [5].

On CT, the findings of PID include dilated fallopian tubes, enlarged ovaries, inflammatory changes in the adjacent pelvic fat, thickening of the uterosacral ligaments, and peritoneal hyperenhancement [4, 7, 8]. The secondary findings which may include small bowel ileus/obstruction, perihepatitis (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome), and ureteral obstruction can be better evaluated on CT [4].

Pelvic infection with Actinomyces israelii is associated with the use of intrauterine contraceptive device. Tubo-ovarian abscesses with actinomycosis usually appear solid and may contain small rim-enhancing lesions. This infection spreads by direct extension, demonstrating linear, enhancing lesions which often have an appearance resembling carcinomatosis.

On MRI, a tubo-ovarian abscess usually presents as a mass which is T1 hypointense, often with hyperintense hemorrhage or proteinaceous debris. There is often a thin rim of T1 hyperintense signal along the inner portion of the abscess, secondary to hemorrhage within a layer of granulation tissue [8]. The abscess is usually hyperintense on T2-weighted sequence. On the postcontrast images, there is enhancement of the abscess wall and adjacent fat stranding [9]. Tubo-ovarian abscesses are hyperintense on diffusion-weighted images and demonstrate diffusion restriction [10].

Endometriosis

In endometriosis, endometrial tissue develops outside the uterine cavity, possibly due to metastatic implantation of endometrial cells from retrograde menstruation [11]. The most common locations for endometriosis include the ovaries (endometriomas), uterosacral ligament, rectosigmoid colon, vagina, and bladder. The ectopic endometrial tissue in endometriosis infiltrates adjacent structures causing an intense desmoplastic reaction, fibrosis, adhesions, and muscular hyperplasia. These changes can result in dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dyschezia, dysuria, back pain with menses, and hematuria [12–14].

Laparoscopy is the gold standard for the diagnosis, staging, and treatment of endometriosis; however, in cases where there is limited mobility of pelvic structures due to extensive fibrosis and adhesions, laparoscopic evaluation may be limited. The goal of imaging is lesion mapping for presurgical planning and postsurgical response evaluation. Transvaginal ultrasound is the first-line imaging technique for initial evaluation of suspected endometriosis.

Imaging

On ultrasound, deeply infiltrating endometrial implants are hypoechoic compared to myometrium. The endometriomas demonstrate diffuse low-level internal echoes and no internal blood flow.

MRI is probably the most specific imaging modality for diagnosing endometriomas. MRI is best for looking at hemorrhagic content, which is hyperintense on fat-suppressed T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images (Fig. 13.5a). The surrounding desmoplastic reaction is hypointense on T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequence [12, 13]. Endometriomas are classically T1 hyperintense and T2 hypointense (described as “T2 shading”) (Fig. 13.5b). Endometriosis may rarely be a cause of hemoperitoneum which can result from rupture of an endometrioma or infiltration and subsequent rupture of the uterine artery [14].

Fig. 13.5

Endometriosis. (a) Axial noncontrast T1-weighted MR image with fat saturation obtained through the pelvis showing multiple endometriotic cysts along bilateral pelvic side walls (arrowheads). The implants appear T1 hyperintense due to methemoglobin content. (b) Axial noncontrast T2-weighted MR image of the pelvis demonstrates a left ovarian endometrioma with a fluid/fluid level (arrow). The dependent contents of the endometrioma demonstrated characteristic “T2 shading” (hypointensity)

Ovarian Torsion

Ovarian torsion occurs when the adnexa twists on the vascular pedicle, often resulting in interruption of the venous flow and enlargement of the ovary. As the torsion progresses, the arterial blood flow is interrupted and ovarian ischemia occurs [15]. The ovary has a dual arterial blood supply which includes the ovarian artery and ovarian branches of the uterine artery. Any ovarian mass or large cyst may place the adnexa at risk of torsion [2, 16].

Torsion is most commonly seen in reproductive-age women with an ovarian mass or cyst found in up to 80 % of cases of torsion. Symptoms of torsion are nonspecific and most commonly include acute abnormal pain. Patients may also experience nausea and vomiting with fever occasionally developing several hours late [17]. Because the clinical presentation is nonspecific, correct diagnosis is often delayed [18].

Imaging

Ultrasound is the preferred initial imaging modality when ovarian torsion is suspected. If the ovaries appear normal in size and morphology on ultrasound, then torsion can be excluded [19]. The most common finding is ovarian enlargement of greater than 4 cm. The ovary may have a teardrop configuration with multiple small follicles displaced to the periphery of the ovary.

Although the absent vascular flow on color Doppler imaging is highly suggestive of torsion, normal Doppler flow does not exclude torsion because early torsion is often intermittent or partial [2, 16]. The “whirlpool sign” refers to visualization of twisted or circular vessels in the vascular pedicle; this is highly specific for adnexal torsion [15, 20].

Occasionally on CT and MRI, twisting of the vascular pedicle can be directly visualized; this finding is highly specific for adnexal torsion (Fig. 13.6) [21]. Most other findings are nonspecific and can include an adnexal mass, ipsilateral deviation of the uterus, lack of contrast enhancement, and ascites. On MRI, diffusion-weighted imaging reveals diffusion restriction when ischemia is present. Ovarian enlargement and edema from torsion result in T2 hyperintensity in the central ovarian stroma, which also shows multiple peripheral follicles.