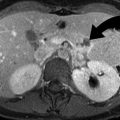

Fig. 7.1

Obstructing left UVJ stone in a 71-year-old male with elevated creatinine and hydronephrosis. (a) Scout view demonstrates a coarse calcification in the left pelvis corresponding to a left UVJ stone as confirmed on subsequent CT images. (b–d) Non-contrast-enhanced CT axial (b) and coronal (c, d) images show a 14 × 6 × 4 mm left UVJ stone (b, c) with soft tissue rim sign (c) and upstream severe left hydronephrosis (d)

Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) is the gold standard for imaging patients with suspected obstructive uropathy. Stone/lesion size, location, and degree of obstruction can be quantified. Non-contrast CT (NCCT) has a sensitivity of 95–98 % and specificity of 96–100 % for detecting urinary stones [3–5]. NCCT is relatively quick, without the use of intravenous or oral contrast, making it particularly useful in the emergency setting. Most stones appear radiodense on CT. Rarely, in HIV patients who are poorly hydrated and treated with indinavir, crystalline stones develop which are radiolucent on NCCT. When findings are negative or equivocal, intravenous contrast can be administered to assess for additional renal or abdominal processes. Besides urinary stones, other etiologies of intraluminal obstruction include blood clots, which are dense but lower in attenuation than calculus; masses, which measure soft tissue attenuation and enhance following contrast administration; and ureteral spasm, strictures, or injury. Extraluminal compression may be caused by retroperitoneal masses, abscess, inflammation, or posttraumatic hematoma [4, 5].

At CT evaluation for ureteral stone, one should focus at the most common locations; narrowing of the ureter occurs naturally at the ureterovesicular junction (UVJ), the pelvic brim as the ureter crosses iliac vessels, and at the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) (Fig. 7.1b, c) [3]. Frequently, a transition point is visible, with urinary decompression more distally. Secondary CT findings in obstructive uropathy include hydroureter, hydronephrosis, perinephric stranding, and possible enlargement of the unilateral kidney (Fig. 7.1d) (Table 7.1). Periureteral wall thickening and perinephric/periureteral fat stranding reflect acute inflammation. The “soft tissue rim sign” is due to edema of the ureteral wall at the site of stone impaction and may help differentiate a ureteral stone from a phlebolith in an adjacent vein (Fig. 7.1c) [6]. Renal edema may be appreciated, with decrease in Hounsfield attenuation on NCCT (“pale kidney” sign). Following contrast administration, there may be delayed excretion of contrast into the collecting system/ureter or beyond the level of obstruction (“delayed nephrogram/urogram”), which may be partial or complete (Fig. 7.2). Pyelosinus or forniceal rupture manifests as a perinephric fluid (Fig. 7.3). In cases of extrinsic compression, the ureter appears abnormally deviated due to mass effect [4, 5, 7].

Table 7.1

CT findings in acute obstructive uropathy

1. Calcified stone in the GU tract |

UVJ, UPJ, and pelvic brim are most common locations |

2. Hydroureter |

3. Hydronephrosis |

4. Soft tissue rim sign |

5. Perinephric/periureteral stranding |

6. Unilateral enlarged kidney |

7. Forniceal rupture |

8. Pale kidney sign |

Fig. 7.2

Delayed excretion of contrast in an 87-year-old female with left abdominal pain. Contrast-enhanced coronal CT image shows left hydronephrosis and delayed excretion of contrast (delayed enhancement) from the left kidney as compared to the right in this patient with an obstructing 9 mm left UPJ stone

Fig. 7.3

Forniceal rupture in a 41-year-old female with left flank pain. (a) Non-contrast-enhanced axial CT image demonstrates 2 mm left UVJ stone. (b) Contrast-enhanced CT axial image demonstrates perinephric fluid consistent with forniceal rupture

Ultrasonography (US) is a useful screening examination for pregnant and pediatric patients, in whom radiation exposure is a concern. The sensitivity for urinary obstruction is 60–70 %, but this is highly operator and patient dependent and involves limited ureteral assessment [8]. Renal stones are echogenic foci with or without shadowing, depending on size, composition, and technique (Fig. 7.4). Smaller stones may blend into the echogenic renal sinus and be missed. Ureteropelvic and ureterovesical junction stones, which lie superficially within good acoustic windows, may be seen. However, mid-ureteral stones are extremely difficult to detect. The finding of hydronephrosis is suggestive but may be absent in early obstruction (false negative) or present due to alternate causes such as pregnancy and reflux (false positive) (Fig. 7.5a). One must distinguish true hydronephrosis from mimics such as parapelvic cysts, extrarenal pelvis, and pelvicaliectasis. Additional signs include absent or decreased ureteral jets and a Doppler arterial resistive index greater than 0.70 (or difference between kidneys greater than 0.10). However, these findings are neither sensitive nor specific [8].

Fig. 7.4

Obstructing left UVJ stone with upstream left hydronephrosis. Ultrasound images show moderate left hydronephrosis (a). Shadowing echogenic focus at the left UVJ is consistent with obstructing stone (b)

Fig. 7.5

A 27-year-old female, 34 weeks pregnant, with right abdominal pain. (a) Ultrasound shows moderate right hydronephrosis. Distal right ureter not visualized and etiology was unclear. (b, c) Subsequent MR imaging shows moderate to severe right hydronephrosis on axial SSFSE HASTE imaging (b) secondary to distal right ureteral stone (c, coronal true FISP)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an alternative to CT, particularly in pediatric and pregnant patients for whom radiation exposure is a concern. MRI offers superior soft tissue contrast, albeit with increased costs and longer scan times. Ultrafast scanning protocols have been developed to image the urinary system with good spatial resolution in multiple planes. Fluid-sensitive T2-weighted sequences, such as single-shot fast spin echo (SSFSE) and balanced steady-state free precession (SSFP), utilize urine as an intrinsic contrast agent [9]. Fat-suppressed sequences are also acquired to enable differentiation from intraperitoneal/retroperitoneal fat. Urinary calculi, which are proton poor, may appear as hypointense filling defects (Fig. 7.5b, c). Stones smaller than 1 cm are frequently not seen – in which case diagnosis relies on signs of urinary obstruction, such as a ureteral transition point [9]. Acute obstruction frequently presents with soft tissue wall thickening, stranding, and edema, manifesting as high T2 signal and loss of renal corticomedullary differentiation. Multiphasic gadolinium-enhanced imaging can be performed using a T1-weighted spoiled gradient echo sequence. This allows assessment of the renal parenchyma, improves urinary-calculi contrast, and quantifies collecting system transit time [9].

Complications and Treatment

In the early stages, acute obstructive uropathy is reversible with minimal renal parenchymal damage. Urinary stones smaller than 5 mm can be managed conservatively and usually pass spontaneously. Large and/or irregularly shaped stones may become impacted, predisposing to infection and collecting system rupture which can result in hematogenous dissemination of infection (urosepsis) [2].

In urgent situations, drainage procedures such as percutaneous nephrostomy, nephroureteral stenting, and suprapubic cystostomy can be performed to decompress the urinary system proximal to the site of obstruction [2].

Infections

Urinary tract infections have accounted for approximately one million emergency department visits annually in the USA [10]. Most of these are uncomplicated and only involve the urinary bladder. However, if the infection migrates proximally or is spread hematogenously, pyelonephritis may ensue.

Acute Pyelonephritis

Urinary tract infections typically begin in the urinary bladder and migrate proximally, leading to tubulointerstitial inflammation. This ascending infection often occurs in the absence of reflux due to the virulence of the bacteria, most commonly gram-negative organisms, in particular Escherichia coli. Pyelonephritis can also occur if the urinary infection is spread to the kidneys hematogenously, from skin infection or endocarditis as may be seen in intravenous drug abusers.

Patients with pyelonephritis tend to present with fever, chills, and flank pain with costovertebral angle tenderness. Symptoms often also include dysuria, urinary frequency, and urgency [10]. Additional symptoms of acute pyelonephritis may include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, which overlap with many other conditions, particularly gastrointestinal. Urinalysis findings include pyuria, bacteriuria, and positive urine culture.

Imaging

The majority of patients respond well to antibiotic treatment and imaging is often not required. However, in certain circumstances, imaging can play an important role in differentiating acute pyelonephritis from other entities causing acute symptoms (particularly if the patient has failed 72 h of antibiotic treatment), detecting structural abnormalities, evaluating patients at high risk for complications, and characterizing the severity of infection and extent of possible organ damage.

MDCT is the preferred imaging modality to evaluate for acute bacterial pyelonephritis. Post-contrast imaging findings include one or more wedge-shaped hypodense areas extending from the papilla to the renal cortex, consistent with a striated nephrogram and representing decreased enhancement compared to the surrounding renal parenchyma (Fig. 7.6a). The findings result from stasis of contrast material within edematous tubules that demonstrates increasing attenuation over time The decreased enhancement or striation is due to reduced perfusion secondary to obstruction of the renal tubules by intraluminal inflammatory debris, interstitial edema, and vasospasm [10]. A “striated nephrogram” can also be seen in GU obstruction, renal vein thrombosis, and contusion [11] (Tables 7.2 and 7.3). On non-contrast-enhanced CT, affected regions of the kidney may be lower in density due to underlying edema, and there may be loss of the renal pyramids. The affected kidney may be enlarged [12]. Renal calculi may be present. Secondary findings due to inflammation in acute pyelonephritis may also include perinephric stranding, thickening of Gerota’s fascia, and hydronephrosis [10, 12].

Fig. 7.6

Acute bilateral pyelonephritis in a 34-year-old female with fever, chills, and right upper quadrant pain. (a) Contrast-enhanced coronal CT image demonstrates bilateral, right greater than left, striated nephrograms with alternating areas of hypodensity representing decreased enhancement. No drainable fluid collection. (b) Ultrasound image shows wedge-shaped echogenic area in the right kidney

Table 7.2

Differential diagnosis of striated nephrogram

1. Acute pyelonephritis |

2. GU obstruction |

3. Renal vein thrombosis |

4. Contusion |

Table 7.3

Imaging of acute pyelonephritis

1. CT and MRI: striated nephrogram |

2. US: often negative but can see hypoechoic or hyperechoic areas |

3. Enlarged kidney |

Ultrasound may be used to evaluate the urinary tract in cases of infection, in particular to assess for hydronephrosis or renal abscess. Occasionally findings of pyelonephritis may be found at ultrasound, although ultrasound is not as sensitive as CT and patients with clinically suspected pyelonephritis often have negative ultrasound results. Changes in the echotexture of the renal parenchyma may be seen and include hypoechoic areas due to edema and hyperechoic regions due to hemorrhage (Fig. 7.6b) [10]. There may be hydronephrosis, renal enlargement, and/or loss of normal corticomedullary differentiation. Regions of hypoperfusion may be seen with color Doppler. Ultrasound is limited in assessing the full extent of pyelonephritis and perinephric extension and in visualizing microabscesses [10].

The use of MRI in the evaluation of acute renal infections tends to be limited to patients who cannot undergo intravenous contrast-enhanced CT (i.e., allergy to IV contrast material), patients in who radiation is a concern, or patients with inconclusive/equivocal CT results. MRI is much more susceptible to patient motion artifact than CT is, and it can be more difficult to obtain high-quality images in sick patients. In acute pyelonephritis, similar to that seen on CT, MRI shows wedge-shaped areas of decreased enhancement of the renal parenchyma on T1 fat-saturated post-contrast images and may show areas of decreased signal on T2-weighted images (Fig. 7.7). Renal enlargement and perinephric fluid may also be seen.