(1)

Department of Radiology, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA

(2)

Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Abstract

Thoracic complaints including cough, shortness of breath, and pleuritic chest pain are common but nonspecific presenting symptoms in the emergency department, and as many as 5 % of visits are due to acute chest pain (19). Acute chest pain in the absence of trauma remains a diagnostic challenge because of extensive etiology that ranges from benign to potentially lethal. After cardiac and aortic etiologies are ruled out, three main categories of disease origin should be considered: mediastinum (including pulmonary vasculature only), lung, and pleura. Nontraumatic, noncardiac mediastinal processes which can present with chest symptoms include, but are not limited to, pulmonary embolism (technically lung but will be considered with mediastinum), esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, and abscess. Pulmonary pathology also tends to affect the pleural space so these two categories will be considered together. Pneumonia and pulmonary edema are the most common pulmonary diagnoses in the emergency room. It is equally important to delineate any associated complications including pulmonary abscess and empyema. Pneumothorax can also be nontraumatic in etiology and present with acute thoracic symptoms (18).

Introduction

Thoracic complaints including cough, shortness of breath, and pleuritic chest pain are common but nonspecific presenting symptoms in the emergency department, and as many as 5 % of visits are due to acute chest pain. Acute chest pain in the absence of trauma remains a diagnostic challenge because of extensive etiology that ranges from benign to potentially lethal. After cardiac and aortic etiologies are ruled out, three main categories of disease origin should be considered: mediastinum (including pulmonary vasculature only), lung, and pleura. Nontraumatic, noncardiac mediastinal processes which can present with chest symptoms include, but are not limited to, pulmonary embolism (technically lung but will be considered with mediastinum), esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, and abscess. Pulmonary pathology also tends to affect the pleural space so these two categories will be considered together. Pneumonia and pulmonary edema are the most common pulmonary diagnoses in the emergency room. It is equally important to delineate any associated complications including pulmonary abscess and empyema. Pneumothorax can also be nontraumatic in etiology and present with acute thoracic symptoms.

Imaging

Although accurate clinical history and physical examination are essential, diagnostic imaging continues to be indispensable in helping to navigate nonspecific thoracic signs and symptoms and reach a more refined assessment.

Chest Radiograph

The first radiological examination obtained on a patient with chest symptoms should be a good quality PA and lateral chest radiograph. Portable technique should be reserved for only those patients who are truly obtunded or too critical to transport to the radiology department. While a CXR is limited in its sensitivity and specificity, it is the most efficient way to quickly evaluate the patient and be able to categorize the management as a surgical issue which may need to be imminently addressed such as a pneumothorax or a non-life-threatening medical process such as pneumonia. Correlation with the patient’s clinical history, immune status, and comorbidities is critical to the proper interpretation of the film.

Chest CT Scan

Chest CT can be helpful to further elucidate subtle findings seen on the chest radiograph. Contrast-enhanced examination should be obtained when possible so that contrast enhancement can better delineate mediastinal and vascular structures and help define and separate pleural and parenchymal processes. Pulmonary embolism protocol is a separate technique and needs to be specifically requested if this diagnosis is a consideration.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound has limited application in the lung and mediastinum but is very useful in delineating the pleural space as to the nature of the contained process. Directed ultrasound can also assist in guidance for diagnostic thoracentesis or drainage catheter placement.

Mediastinum

Pulmonary Embolism

Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) is the third most common cause of cardiovascular death, with an average incidence in the USA of 1 per 1,000 persons. Approximately 300,000 patients die from PE each year. The most common signs and symptoms at the time of presentation include dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, tachypnea, and tachycardia [1]. The classic clinical triad of chest pain, dyspnea, and hemoptysis is only seen in a minority of patients. Common risk factors for PE include acute medial illness, prolonged immobilization, malignancy, and orthopedic surgery.

The chest radiograph is usually the first imaging examination obtained in the evaluation of patients presenting with chest pain and can be used to detect other potential causes of symptoms mimicking PE, including pneumonia, pulmonary edema, and pneumothorax. Several classic radiographic signs of PE have been described, but are infrequently encountered. These include Westermark’s sign, which is increased lucency of all or portion of a lung secondary to decreased vascular flow in the setting of obstructive PE. Hampton’s hump is a peripheral, wedge-shaped opacity that may represent pulmonary infarction in the setting of PE [2].

Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy is performed with the intravenous injection and inhalation of radiopharmaceuticals for the purpose of identifying PE. It is most valuable in the setting of a normal chest radiograph, as pulmonary parenchymal disease limits its sensitivity and specificity. The presence of a ventilation-perfusion mismatch, or a defect on the perfusion study only, is suggestive of PE. The Prospective Investigation of Pulmonary Embolism II (PIOPED II) interpretation scheme is used in the reporting of the ventilation-perfusion scan. The diagnostic categories include normal, very low probability, low probability, intermediate probability, and high probability. Many patients have scans between low and high probability and require additional testing for diagnosis [3].

Pulmonary angiography has traditionally been considered the gold standard examination to evaluate for PE. However, multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) with intravenous contrast has now surpassed angiography and is the primary modality utilized for diagnosis of PE in most institutions. Factors contributing to the effectiveness of CT over pulmonary angiography include widespread availability and fast scan times. Additionally, ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy and pulmonary angiography do not accurately demonstrate subsegmental PE. In addition to demonstrating PE within the main, lobar, and segmental PE, MDCT is more accurate in identifying PE affecting the subsegmental pulmonary arteries. In addition to identifying PE, CT can evaluate the remainder of the chest for abnormalities such as pneumonia, pulmonary edema, and pneumothorax. The most common finding on contrast-enhanced CT is hypodense filling defects within opacified pulmonary artery branches (Fig. 23.1) [4]. Saddle emboli, or pulmonary emboli bridging the main pulmonary arteries, may be seen. Abrupt vessel cutoff and complete occlusion may be identified. Cardiac dysfunction in the setting of massive acute PE may manifest as enlargement of the right atrium and ventricle, straightening of the interventricular septum, or bowing of the interventricular septum towards the left ventricle (Fig. 23.2) [5]. The most common finding within the lung parenchyma in patients with PE is atelectasis. Pulmonary infarction may be seen within the peripheral aspects of the lung parenchyma and typically manifests as wedge-shaped ground glass or mixed ground glass and solid opacities (Fig. 23.3). A thickened vessel may be seen extending to the margin of the opacity. Infarction is more common in patients with impaired collateral circulation and pulmonary venous hypertension. Pleural effusions may also be present [6].

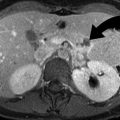

Fig. 23.1

Pulmonary embolism. (a, b) Axial CT images show filling defects (arrowheads) within the right and left pulmonary arteries, as well as segmental pulmonary arterial branch in right lower lobe

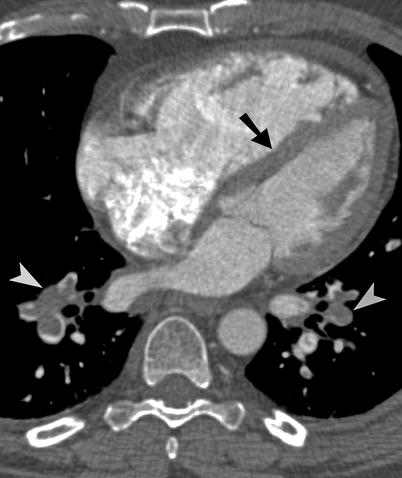

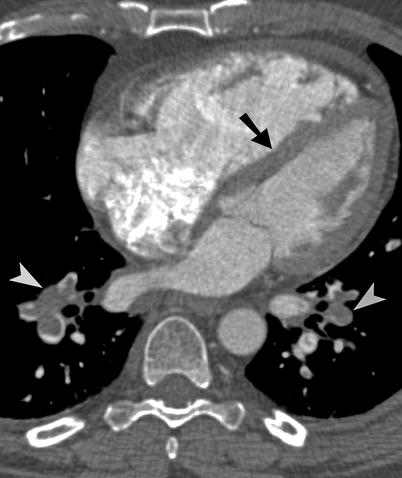

Fig. 23.2

Pulmonary embolism. Axial CT image shows extensive pulmonary emboli (arrowheads) within the lower lobes. Straightening of the interventricular septum (arrow) is consistent with right cardiac dysfunction

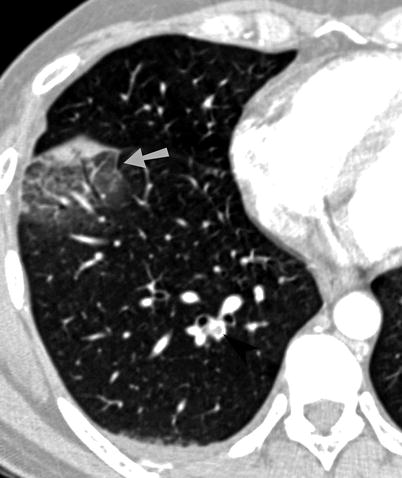

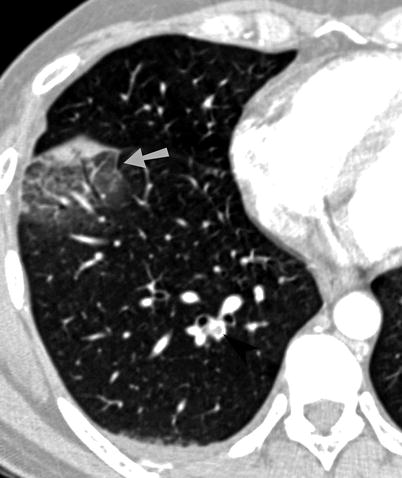

Fig. 23.3

Pulmonary embolism and infarction. Axial CT image demonstrates a mixed ground-glass and solid opacity within the right lower lobe along the major interlobar fissure. This opacity represents pulmonary infarction (arrow) in this patient with pulmonary emboli (arrowhead)

Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal perforation is a potentially life-threatening phenomenon. The most common etiology of esophageal perforation is iatrogenic, usually associated with endoscopic instrumentation and thoracic surgery. The rate of perforation associated with endoscopy has been estimated at approximately 1 per 1,000. In one series, perforation was iatrogenic in 55 % of cases. Traumatic perforation is most common within the cervical portion of the thoracic esophagus, which is the narrowest portion. Other etiologies include spontaneous perforation (Boerhaave’s syndrome) in 15 %, foreign body in 14 %, and blunt or penetrating trauma in 10 %. Underlying esophageal disease, such as esophagitis or malignancy, appears to place patients at an increased risk of rupture [7].

Boerhaave’s syndrome or spontaneous esophageal perforation is a rare phenomenon, affecting approximately one per 6,000 patients [7]. Perforation is typically due to an episode of violent vomiting. In this scenario, the posterior esophagus ruptures, usually near the crus of the left hemidiaphragm. The most common clinical symptoms include history of vomiting, chest pain, and fever. Subcutaneous emphysema may be present on physical examination [7, 8]. The role of conventional chest radiography in the assessment of esophageal perforation is limited, and initial radiographs may be normal. The most common abnormalities are characterized as indirect signs of esophageal perforation and include pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and pleural effusion (Fig. 23.4) [7, 8].

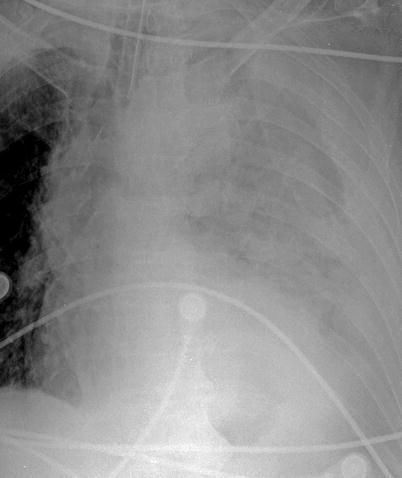

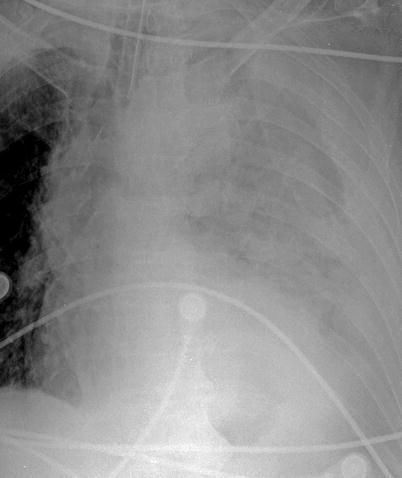

Fig. 23.4

Boerhaave’s syndrome. Frontal chest radiograph demonstrates a left pleural effusion and near-complete opacification of the left hemithorax in this patient with Boerhaave’s syndrome

Pneumomediastinum may appear as visualization of the white pleural line adjacent to the mediastinum, areas of radiolucency in the soft tissues, and focal air collections within the mediastinum and retrosternal region. The “continuous diaphragm sign,” a linear collection of air along the diaphragm, and “V sign” of Naclerio, a collection of air along the left paraspinal region above the left hemidiaphragm, are well-described signs of pneumomediastinum that are rarely seen. CT is definitive in demonstrating the presence of pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and pleural effusion complicating esophageal perforation.

If oral contrast material is used at the time of CT imaging, extravasation of contrast from the esophageal lumen into the mediastinum or pleura may be present (Fig. 23.5). Esophagography had previously been considered the initial examination of choice in the evaluation of uncomplicated esophageal disease. In the event of esophageal perforation, esophagography should be performed with water-soluble contrast material, which is rapidly absorbed by the mediastinum. However, water-soluble contrast material should not enter the tracheobronchial tree, as its hyperosmolar composition may result in pulmonary edema. Contrast esophagography may demonstrate extravasation of intraluminal contrast material into the mediastinum or pleura (Fig. 23.6). However, false-negative results may be encountered 10 % of the time [7].

Fig. 23.5

Esophageal perforation. (a) Axial CT image through the upper chest shows extensive pneumomediastinum (arrowheads) and a left pleural effusion. (b) Axial CT images of the same patient demonstrate a defect (arrow) within the left lateral wall of the distal thoracic esophagus. An extraluminal collection of air and contrast material (arrowhead) is present to the left of the esophageal wall defect.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree