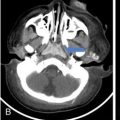

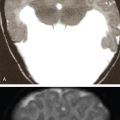

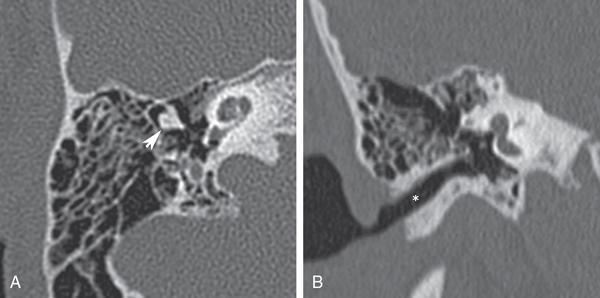

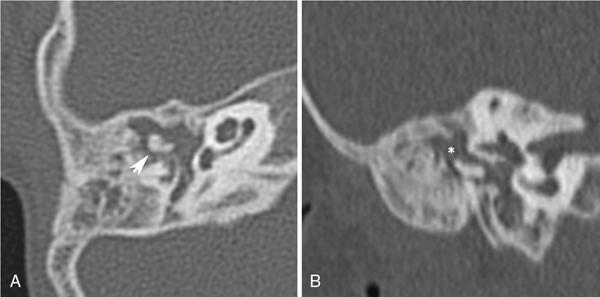

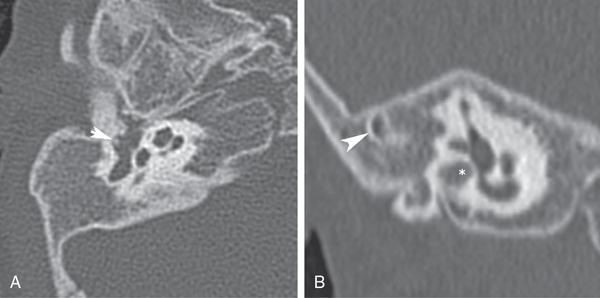

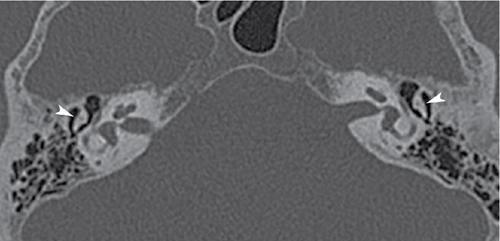

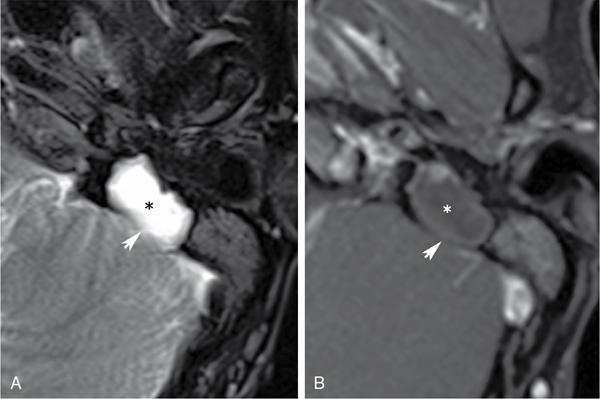

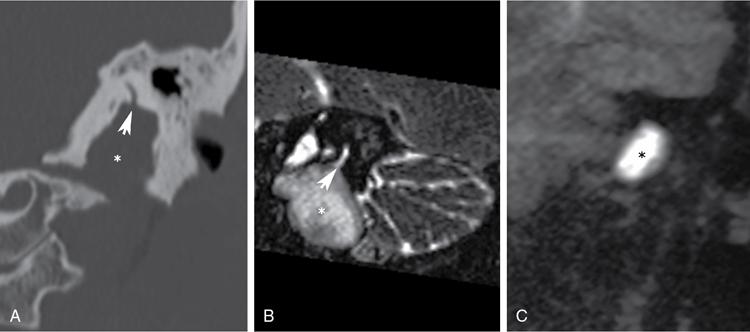

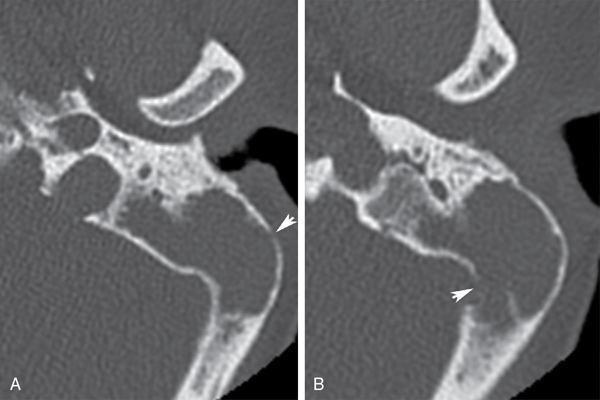

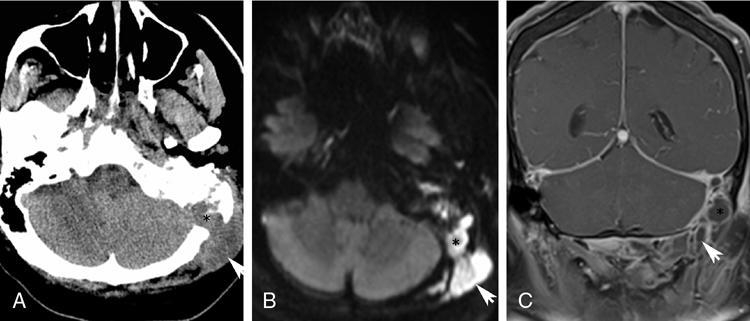

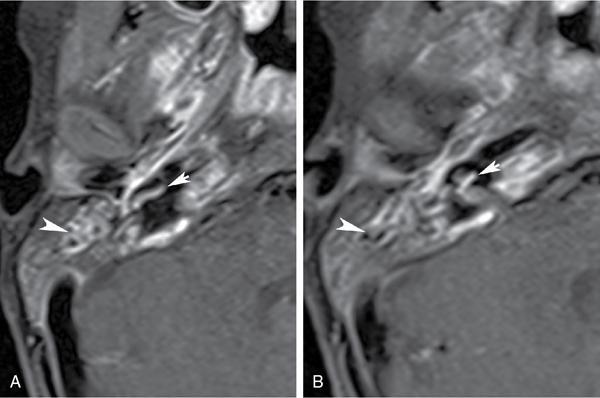

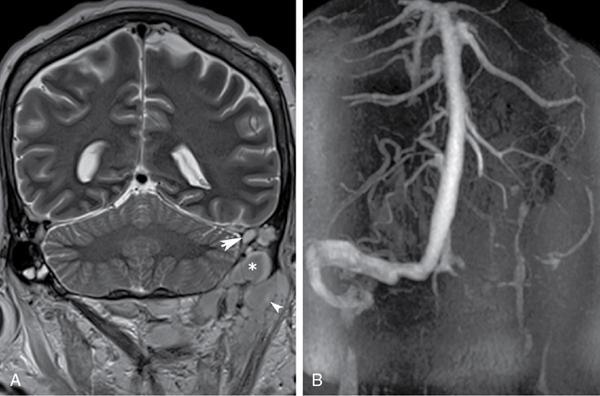

Shivaprakash B. Hiremath, Santanu Chakraborty The temporal bone is one of the most complex regions of the head and neck. Adequate awareness of the intricate anatomy and imaging findings of the middle ear pathologies is paramount for the radiologist to arrive at an accurate diagnosis. CT is optimal for evaluating the bone detail and assessment of the ossicular pathologies, hence cornerstone in imaging diagnosis of the middle ear. MRI, in particular, is reserved for the evaluation of small and recurrent cholesteatoma and middle ear tumours. This chapter focuses on congenital anomalies, middle ear infections and temporal bone trauma, followed by middle ear tumours. Congenital malformations of the ear are not uncommon and may affect the external ear, middle ear or inner ear in isolation or more often in combination. Of these, middle ear malformations are rare and commonly associated with malformations of the external ear. Various classification systems are proposed to describe the anomalies for ease of understanding and communication. The classification schemes categorize middle ear anomalies into three groups – combined external and middle ear malformations, isolated middle ear malformations and anomalies as a part of a more generalized syndrome. Of the numerous proposed classification systems, the commonly used include Altmann’s classification for the external and middle ear anomalies, Kosling’s classification for isolated middle ear malformations and Teunissen and Cremer’s classification for ossicular malformations. The embryological development of the external ear and that of the middle ear are closely related; the combined occurrence of the malformations is well known. The inner ear develops earlier than the external and middle ear. Inner ear anomalies are not typically associated with external and middle ear malformations unless part of the syndrome. Nonsyndromic congenital external and middle ear malformations (CEMEMs) are usually unilateral, while bilaterality is familiar with syndromic CEMEMs. Based on the severity of involvement, the combined external and middle ear malformations are classified by Altmann into three groups: The associated ossicular malformations include incudomalleolar fusion with fixation to the epitympanic recess (Fig. 3.32.4), bony ankylosis between the neck of the malleus and atretic external auditory canal, and hypoplastic manubrium of the malleus. Rarely, malleus and incus may be absent. Uncommon findings include hypoplasia of stapes, stapes fixation and facial nerve encroachment on the stapes. The isolated malformations of the middle ear associated with normal external ear and tympanic membrane may go undetected by physicians. High-resolution CT (HRCT) is invaluable in the diagnosis of congenital isolated middle ear malformations (CMEMs) and aids in presurgical evaluation. Based on increasing severity, Kosling et al. classified isolated middle ear malformations into three types: Isolated ossicular malformations without the involvement of the tympanic cavity are rare and labelled as minor middle ear deformities. They are usually associated with high riding jugular bulb and aberrant course of the internal carotid artery. Teunissen and Cremers classify the minor middle ear deformities involving ossicles into four types: Of the various syndromes associated with CEMEMs, the commonly encountered are Klippel–Feil syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome, Branchio-oto-renal syndrome and Treacher Collins syndrome. The CEMEMs with the syndromic association are usually bilateral and may be associated with coexisting inner ear anomalies in up to 10% of cases. Congenital middle ear cholesteatoma (CMEC) occurs due to embryonic epithelial cell rests, leading to the sac of keratinized squamous epithelium in the middle ear cavity with an intact tympanic membrane (Figs 3.32.5 and 3.32.6). CMEC lacks a previous history of surgery, tympanic membrane perforation, middle ear infections or ear discharge. Congenital cholesteatoma typically presents in the second decade with unilateral hearing loss and demonstrates a slight male preponderance. On otoscopic examination, they appear as a pearly white mass in the middle ear cavity behind an intact tympanic membrane. Congenital cholesteatomas are commonly encountered in the anterosuperior quadrant and rarely located in the posterosuperior quadrant, mesotympanum and atticoantral locations. Common associations of CMEC include external auditory canal atresia, congenital ossicular malformations, cholesterol granuloma and vestibular malformations. They are subdivided by Kazahaya and Potsic into four stages, including the following: Complete surgical extirpation is the treatment of choice. Smaller anterior lesions have a better prognosis than the large and posterior lesions associated with an increased recurrence rate. Acute otitis media (AOM) is secondary to the spread of upper respiratory tract infections to the middle ear cavity via the eustachian tube. The eustachian tube is prone to obstruction from adenoid hypertrophy and its relative horizontal position. AOM is the most common localized infection in early childhood and may be associated with spontaneous tympanic membrane perforation in 7%–30% of cases. They rarely require imaging evaluation as they are usually self-limiting with favourable response to antibiotic therapy. Approximately 1%–18% of delayed or untreated otitis media may present with extracranial complications such as neck abscesses, intracranial complications including meningitis, cerebral and extraaxial abscesses and vascular thrombosis. Streptococcus and Haemophilus influenzae attribute to most bacterial infections. Tuberculous and fungal mastoiditis may be considered in patients with persistent otorrhoea, nonresponsive to standard antibiotic therapy. The mucoperiosteal inflammatory changes in the middle ear cavity, and the mastoid air cells result in serous, mucoid or purulent fluid collections. The presence of serous fluid in the mastoid air cells in the absence of infection and inflammatory findings is termed serous otitis media. The uncontrolled disease process may obstruct the aditus ad antrum secondary to mucosal oedema, resulting in accumulation of trapped secretions in the mastoid antrum and air cells with eventual acute mastoiditis. Chronic persistent middle ear effusion with sclerosis of the mastoid air cells in the absence of bone resorption and periostitis is called incipient mastoiditis. In unarrested inflammation, the purulent fluid under pressure results in local acidosis and bone demineralization, decreased blood supply and resorption of the intervening bony septae in the mastoid air cells. This results in the coalescence of mastoid air cells into a large cavity filled with purulent material and granulation tissue, termed coalescent mastoiditis. The bone resorption may progress laterally resulting in a neck abscess, posteriorly into the intracranial compartment leading to an epidural abscess, subdural empyema, venous sinus thrombosis and meningitis. The coalescence of mastoid air cells from osteoclastic activity and bone demineralization leads to coalescent mastoiditis. The HRCT of the temporal bone demonstrates loss of intervening bony septa with likely erosion of the sigmoid plate and the mastoid cortex (Fig. 3.32.7). The medial extension into the petrous air cells leads to petrositis, and the mastoid cortex erosion may lead to subperiosteal abscess formation, extending into the infratemporal fossa. Rarely, the anterior extension into the temporomandibular joint may lead to osteoarthritis and bony ankylosis in undertreated patients. The initial evaluation should include the assessment of the lateral mastoid cortex for the presence of erosion and subperiosteal abscess (Fig. 3.32.8A and B). The mastoid cortex erosion may be associated with purulent collection along the sternomastoid, termed Bezold’s abscess. It is common in adults compared to children under 5 years, owing to incomplete mastoid pneumatization in children. Involvement of the petrous apex is associated with deep-seated auricular pain termed as Gradenigo syndrome (involvement of the Gasserian ganglion), diplopia (abducents nerve involvement at Dorello’s canal) and ear discharge. Other intratemporal complications include labyrinthitis on the affected side (Fig. 3.32.9), secondary to the spread of infection through the oval or round window and rarely facial nerve paralysis typically due to involvement of the tympanic and proximal mastoid segment of the facial nerve. The erosion of the posterior mastoid cortex may lead to perisinus and epidural abscess formation. The epidural abscess typically occurs in the posterior fossa secondary to the erosion of the Trautmann’s triangle overlying the sigmoid sinus, along with rare occurrences in the middle cranial fossa. The middle ear infections may also extend into the subdural space, resulting in subdural empyema rarely containing air foci, typically along the interhemispheric fissure and the tentorium cerebelli causing subdural space widening and adjacent cerebral sulcal effacement. Other intracranial complications include otogenic parenchymal abscess, meningitis, encephalitis and hydrocephalus. In most cases, otogenic parenchymal abscess involves the temporal lobe and cerebellum on the affected site. Meningitis is most often secondary to the haematogeneous spread of infection (Fig. 3.32.8C). The perisinus abscess is associated with sigmoid and transverse sinus thrombosis in more than half of the patients (Fig. 3.32.10). The dural venous sinus thrombosis appears as increased attenuation of the involved vein on unenhanced CT with a nonenhancing filling defect on CT venography. On MRI, they demonstrate loss of normal flow void signal in the thrombosed vein with loss of flow-related hyperintensity on time-of-flight venogram. They may rarely be complicated by cerebellar infarction and haemorrhage. Sigmoid venous sinus thrombosis may also extend into the jugular vein and other dural venous sinuses.

3.32: Imaging the middle ear

Imaging the middle ear

Congenital malformations of the middle ear

Congenital external and middle ear malformations

Congenital isolated middle ear malformations

Syndromic association of middle ear malformations

Congenital middle ear cholesteatoma

Acute and chronic infections of the middle ear

Acute otitis media

Pathophysiology and complications

Imaging findings in acute otitis media

Intratemporal and extracranial complications.

Intracranial complications.

Vascular complications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree