Pulmonary nodules are the most common incidental finding in the chest, particularly on computed tomographs that include a portion or all of the chest, and may be encountered more frequently with increasing utilization of cross-sectional imaging. Established guidelines address the reporting and management of incidental pulmonary nodules, both solid and subsolid, synthesizing nodule and patient features to distinguish benign nodules from those of potential clinical consequence. Standard nodule assessment is essential for the accurate reporting of nodule size, attenuation, and morphology, all features with varying risk implications and thus management recommendations.

Key points

- •

Pulmonary nodules are the most common incidental finding in the chest, particularly on computed tomography (CT) examinations that include some or all of the chest.

- •

Several nodule features may suggest benignity and obviate dedicated chest CT follow-up imaging, whereas others require follow-up.

- •

Accurate reporting of pulmonary nodules is necessary for characterization in terms of size, attenuation, and morphology.

- •

Solid and subsolid pulmonary nodules confer differing risks for malignancy. Societal guidelines exist for managing incidental nodules and distinguish the 2 nodule types when recommending management strategy.

Introduction

Computed tomography (CT) increasingly is utilized, with abdominal and chest CT accounting for approximately two-thirds of all CT examinations. Similarly, the detection rate of pulmonary nodules, defined as a solid, semisolid, or ground-glass focus measuring less than 3 cm, has increased, from 3.9 to 6.6 per 1000 person-years between 2006 and 2012. Many CT-detected pulmonary nodules may be incidental or found on examinations performed for other indications, which can include part (eg, neck CT or abdominal CT) or all of the chest (either alone or including other parts of the body, such as in the setting of trauma).

In a review of 1708 CT pulmonary angiograms, pulmonary nodules represented the most common incidental finding (83 of 223 patients; 37.2%), with further imaging recommended for the majority (86%) of the incidental nodules. An earlier review similarly showed further recommendations were specified for 96% of patients with new incidental nodules, based on existing guidelines at that time. Incidental nodules are frequently identified on CT scans focused on extrapulmonary anatomy, for example, in 12% to 18% of cardiac CTs, with a majority of patients then undergoing further imaging or investigation (33/61 and 74/81 patients, respectively) and potentially further management if proving to be lung cancer.

Given their frequency and potential clinical significance, reporting and management guidelines have been established to address the incidentally detected pulmonary nodule. An understanding of available guidelines and the rationale behind the recommendations is critical to all radiologists, both generalists and body and thoracic imagers, when interpreting chest CT. This article reviews the technical considerations in evaluating and reporting both solid and subsolid pulmonary nodules, and the application of currently available guidelines for nodule management.

Technical and reporting considerations in nodule evaluation

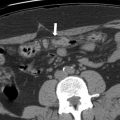

Pulmonary nodules are characterized in terms of attenuation, size, and interval change. Accurate, consistent characterization and description of nodules and attention to CT technique are essential. Pulmonary nodules are best evaluated on CT scans acquired at full inspiration, with reconstructions in contiguous thin sections of 1.5 mm or smaller thickness. Pulmonary nodules should be evaluated on the high-frequency, sharp reconstruction algorithm in lung windows. The soft tissue low-frequency reconstruction algorithm is helpful for assessing pulmonary nodule features, such as calcification, because images are less noisy than high-frequency algorithm reconstructions.

When measuring pulmonary nodules, all ground-glass or cystic components should be included in total nodule size. For subcentimeter nodules, the average of long-axis and short-axis dimensions should be reported, whereas bidirectional measures are provided for nodules greater than 1 cm in maximum dimension. Any solid component of subsolid nodules (SSNs) is reported as the longest dimension of the largest area ( Fig. 1 ). All nodules should be reported to the nearest millimeter. Nodules less than 3 mm are considered micronodules, for which measurement is not necessary.

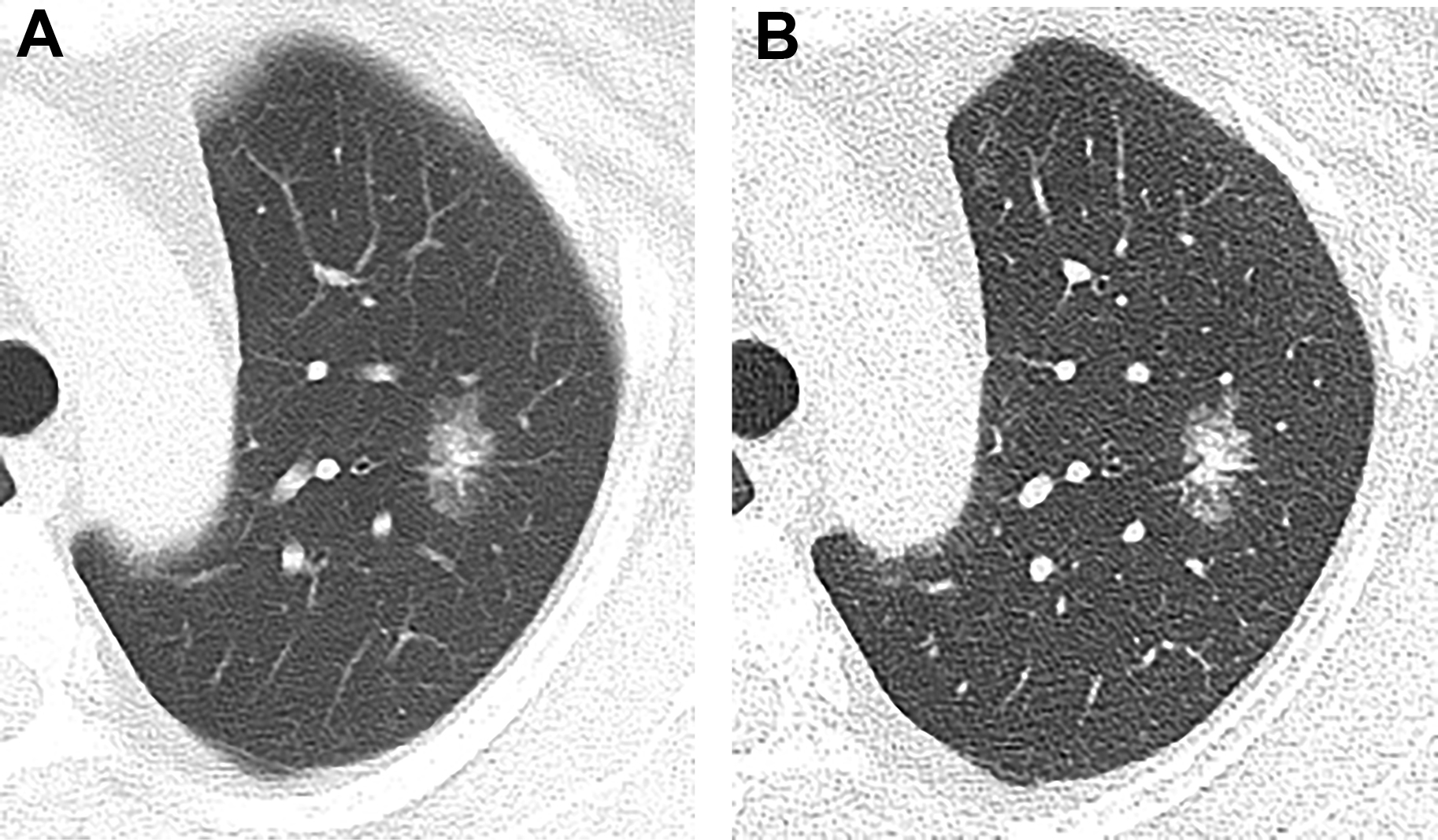

Imagers still may encounter pitfalls in characterizing lung nodules, even with current CT technology. For example, thick-section images may cause a solid nodule to appear subsolid due to volume averaging, as may motion. Review of multiplanar sagittal and/or coronal reformatted images may prevent additional interpretive pitfalls. In the axial plane, small fissural or bandlike foci may appear subsolid, while actually triangular or linear in other planes. Areas of paraspinal or apical opacity may similarly appear nodular in 1 plane, and evaluating multiplanar reformatted images may help distinguish true nodularity from fibrosis ( Fig. 2 ). Perifissural nodules (PFNs) can be morphologically assessed in 3-dimensions as well.

Management guidelines: general concepts

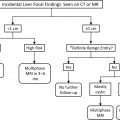

Incidental nodule management and decision making are pursued on a case-by-case basis, guided by imaging features, patient risk, and patient preference. Existing guidelines for incidentally detected pulmonary nodules include those from the Fleischner Society ( Fig. 3 ), the British Thoracic Society (BTS), and the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP). The data used to make these guidelines are informed by lung cancer screening trials, including the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), the Nederlands-Leuvens Longkanker Screenings Onderzoek (NELSON) trial, and the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program (I-ELCAP). Although these trials were conducted for lung cancer screening, they also give substantial insight into the natural history of solid and subsolid pulmonary nodules.

Attention to the patient population addressed by nodule management guidelines is crucial. Although the Fleischner guidelines are restricted to adults ages 35 years or older, the BTS and ACCP guidelines are applicable to incidental nodules in adults of any age. The Fleischner guidelines should be used only in nonimmunocompromised individuals with no known malignancy, because those factors affect the likelihood of infection or malignancy.

Solid nodules and SSNs are managed differently, because their etiologies and clinical behavior differ. For example, lung cancers appearing as solid nodules and those as SSNs have different growth rates, thus influencing the time interval for subsequent follow-up CT. For this reason, the most recent Fleischner guidelines address solid nodule and SSN management independently.

Nodule management algorithms from the Fleischner Society, BTS, and ACCP all address patient risk of malignancy. In the ACCP guidelines, the pretest probability of malignancy for solid nodules can be assessed either by clinician judgment or through quantitative, validated risk prediction models to categorize patients into high-risk (>65%), intermediate-risk (5%–65%), and low-risk (<5%) categories. The Fleischner guidelines also support patient risk assessment, and have high-risk and low-risk categories for solid nodules (see Fig. 3 ); they consider the ACCP high-risk and intermediate-risk groups as the high-risk category. Determining malignancy probability is based on clinical factors, including age, smoking history, and cancer history, and nodule features, such as nodule size, margin, and lobar location. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET and histopathology also are incorporated into the ACCP malignancy risk assessment.

Risk calculators have been validated to assess the likelihood of nodule malignancy, and primarily address solid nodules. Risk calculators incorporate malignancy predictors. For example, in the Brock model, which is based on data from the Pan-Canadian Early Detection of Lung Cancer Study, patient risk factors for malignancy include older age, female sex, family history, and emphysema; and nodule risk factors include larger size, spiculation, upper lobe location, and subsolid attenuation. Risk calculators have optimal performance when applied to populations similar to those on which the model was based. ,

Incidental solid pulmonary nodule management

Incidental solid pulmonary nodules may be consigned to benignity if certain CT features are present, including long-term stability, characteristic benign calcium patterns, or macroscopic fat. Primary considerations for solid nodules include granulomatous disease, lung cancer, solitary pulmonary metastases, hamartoma, and carcinoid tumors ( Table 1 ). The possibility of vascular AVMs and aneurysms may be clarified on intravenous contrast–enhanced examinations. In the absence of prior imaging or characteristic morphology, incidental solid nodules may be indeterminate.

| Nodule Attenuation | Benign | Neoplastic/Malignant |

|---|---|---|

| Solid |

|

|

| Solid with calcifications |

|

|

| Subsolid |

|

|

| Cystic/cavitary |

|

|

Nodules with Calcification or Fat

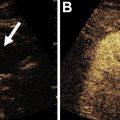

Nodules may demonstrate several calcification patterns on CT ( Figs. 4 and 5 ). Diffuse or completely calcified nodules most often represent benign calcified granulomas. Calcified granulomas are the sequela of prior infection, such as tuberculosis or histoplasmosis, and are a common incidental finding, in 57% of an 872-person agrarian cohort, for example. Uncommonly, certain cancer metastases, however, may present as calcified or ossified nodules, including those from sarcomas, thyroid, or mucinous adenocarcinomas.

Typically, benign calcification patterns also include central calcification, lamellated calcification, or popcorn calcification; the BTS guidelines recommend no follow-up for nodules demonstrating these calcification patterns. Central and laminated calcification may be seen in granulomatous nodules. Popcorn calcifications, round or with rings and arcs, are characteristic of hamartoma and also may be seen in pulmonary amyloid or chondroid nodules or masses. It may be difficult to characterize this from dystrophic calcification on CT, and surveillance CT or PET may be pursued. In a series of 47 hamartomas, 26% were reported to have calcification.

Punctate or amorphous calcifications are indeterminate and have been reported in carcinoid tumors and lung neoplasms. 68 Gallium-dotatate PET (somatostatin-receptor functional imaging) may help differentiate carcinoid from hamartoma, although granulomas also may have somatostatin receptors.

Macroscopic fat within a pulmonary nodule on CT usually is considered pathognomonic for benign hamartoma ( Fig. 6 ). Siegelman and colleagues found 38% of hamartomas in their series of 47 cases to show fat. Other rare causes of fat-containing pulmonary nodules include pulmonary lipoma and metastases from fat-containing primaries, such as liposarcoma or renal cell carcinoma. Lipoid pneumonia also may result in opacities with fat attenuation. The BTS guidelines recommend no follow-up for nodules with macroscopic fat.