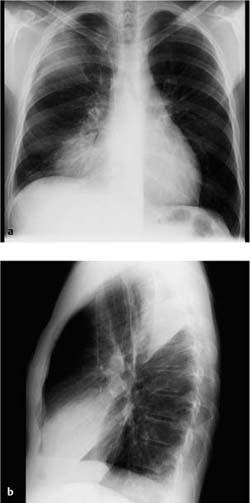

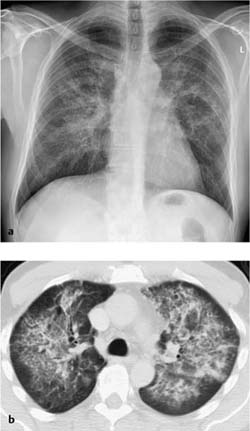

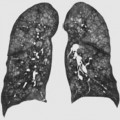

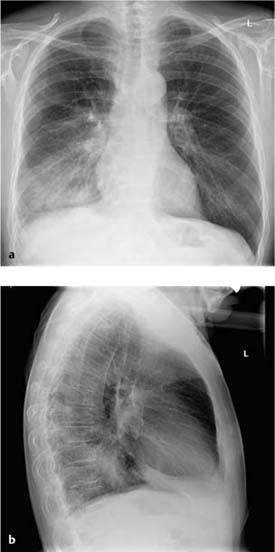

4 Infections Pneumonia acquired in normal, daily life. Diagnostic microbiologic evaluation is carried out in less than 30% of cases of community-acquired pneumonia; the pathogen can be positively identified in only 5% of cases These depend on the pathogen. Pneumococci, Klebsiella, Legionella, and Myco-plasma typically cause lobar consolidation. Haemophilus influenzae and staphylococci cause bronchopneumonic infiltrates, and viruses and mycoplasmas cause interstitial or mixed interstitial-alveolar infiltrates. Radiographs Homogeneous, nonsegmental area of opacification with a pleural interface and alveolar and/or lobar infiltrates Findings are similar to radiography See “Radiographic findings.” Fever, cough, dyspnea, sputum, chest pain, poor general health Antibiotics (empirical therapy). Manifestation and course depend on the specific patient and the infecting pathogen (comorbidities and virulence, respectively) Fig. 4.1 Community-acquired pneumonia in a 55-year-old man. Typical findings in lobar pneumonia. Homogeneous area of infiltrate in the right lower lobe with broad pleural contact. Slight pleural effusion. Confirmation of tentative diagnosis of pneumonia Radiographic findings alone cannot point to a specific causative pathogen. However, this is not necessary as clinical and radiographic findings are together only suggestive and empirical treatment regimens are available. When imaging findings are interpreted in conjunction with clinical data, findings are usually suggestive Franquet T. Imaging of pneumonia: trends and algorithm. Eur Resp J 2001; 18: 196–208 Herold CJ, Sailer JG. Community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonias. Eur Radiol 2004; 14 (Suppl. 3): E2 – E20 Traver RD et al. Radiology of community acquired pneumonia. Radiol Clin North Am 2005; 43: 497–512 Washington L, Palacio D. Imaging of bacterial pulmonary infection in the immunocompetent patient. Semin Roentgenol 2007; 42: 122–145 Pneumonia acquired in a treatment facility. Estimated prevalence in intensive care units is 10–50% There are several reasons for the high prevalence Radiographs There is a broad spectrum of infiltrative changes, which depend on the risk factors. Changes may be focal, unilocular, multilocular, or may include pleural effusion See the various forms of pneumonia for specific findings. Hospitalized patients with multiple disorders may not always show typical symptoms pointing to pneumonia. Therefore diagnostic radiography has a particularly important role in excluding other foci of infection. Specific antibiotics in patients in whom the pathogen has been isolated or empirical treatment for those in whom this is not possible. Fig. 4.2 Hospital-acquired pneumonia in a 57-year-old woman (Pneumocystis pneumonia and fungal pneumonia secondary to perforation of the sigmoid colon). The plain chest radiographs show extensive nodular confluent infiltrates in both lungs with much of the opacity consisting of acinar nodules. The peripheral subpleural parenchymal segments have largely been spared. There was no pleural effusion or lymphadenopathy. Mortality has been cited at 20–50%. Confirm or exclude pneumonia Comorbidities may render clinical and radiologic diagnosis and differential diagnosis difficult

Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Definition

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

Pneumococci (Streptococcus pneumoniae), Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and viruses (adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus) are the most common pathogens; less common pathogens include Legionella pneumophila, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae

Pneumococci (Streptococcus pneumoniae), Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and viruses (adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus) are the most common pathogens; less common pathogens include Legionella pneumophila, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae  Protozoans and fungi are practically never the cause

Protozoans and fungi are practically never the cause  The spectrum of pathogens varies depending on seasonal, geographic, socioeconomic, and intrinsic factors (age, comorbidity).

The spectrum of pathogens varies depending on seasonal, geographic, socioeconomic, and intrinsic factors (age, comorbidity).

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Imaging Signs

Modality of choice

Modality of choice

CT is indicated only where findings are equivocal or there is clinical suspicion but no radiographic correlate.

CT is indicated only where findings are equivocal or there is clinical suspicion but no radiographic correlate.

Radiographic findings

Radiographic findings

Ill-defined focal heterogeneous opacities in a segmental configuration with bronchopneumonic infiltrates.

Ill-defined focal heterogeneous opacities in a segmental configuration with bronchopneumonic infiltrates.

CT findings

CT findings

CT is more sensitive in detecting associated findings (multifocal manifestation, pleuritis, liquefaction).

CT is more sensitive in detecting associated findings (multifocal manifestation, pleuritis, liquefaction).

Pathognomonic findings

Pathognomonic findings

Clinical Aspects

Typical presentation

Typical presentation

Leukocytosis with leftward shift

Leukocytosis with leftward shift  It is usually not possible to identify the pathogen as noninvasive diagnostic evaluation (sputum analysis) is inefficient and delayed.

It is usually not possible to identify the pathogen as noninvasive diagnostic evaluation (sputum analysis) is inefficient and delayed.

Therapeutic options

Therapeutic options

Course and prognosis

Course and prognosis

Uncomplicated disease resolves completely.

Uncomplicated disease resolves completely.

What does the clinician want to know?

What does the clinician want to know?

Extent of findings.

Extent of findings.

Differential Diagnosis

Tips and Pitfalls

Radiographic findings are negative in this regard in about one-third of patients with clinically suspected pneumonia

Radiographic findings are negative in this regard in about one-third of patients with clinically suspected pneumonia  Usually these cases are severe, clinically relevant respiratory infections.

Usually these cases are severe, clinically relevant respiratory infections.

Selected References

Hospital-Acquired (Nosocomial) Pneumonia

Definition

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

Pathogens predominantly include both Gram-negative pathogens (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella ssp., Enterobacteriaceae, Proteus ssp., Escherichia coli, Serratia marcescens) and Gram-positive cocci (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus), Legionella, and viruses

Pathogens predominantly include both Gram-negative pathogens (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella ssp., Enterobacteriaceae, Proteus ssp., Escherichia coli, Serratia marcescens) and Gram-positive cocci (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus), Legionella, and viruses  Mixed infections are common

Mixed infections are common  Despite intensive serologic, immunologic, and microbiologic diagnostic testing, a specific pathogen can be identified in only about one-third of all cases (it can be difficult to distinguish infection from contamination).

Despite intensive serologic, immunologic, and microbiologic diagnostic testing, a specific pathogen can be identified in only about one-third of all cases (it can be difficult to distinguish infection from contamination).

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Patient-related factors include age, immune status, a previous or underlying disorder, and aspiration

Patient-related factors include age, immune status, a previous or underlying disorder, and aspiration  Risks related to treatments include breaching of physiologic barriers by intubation and artificial respiration, catheters, and antacid medications

Risks related to treatments include breaching of physiologic barriers by intubation and artificial respiration, catheters, and antacid medications  Environmental risks include staff and other patients.

Environmental risks include staff and other patients.

Imaging Signs

Modality of choice

Modality of choice

CT is indicated only where findings are equivocal or to rule out other pathology.

CT is indicated only where findings are equivocal or to rule out other pathology.

Radiographic and CT findings

Radiographic and CT findings

Note that repeated follow-up examinations are indicated not only to confirm or exclude complications but also for diagnostic purposes as it is difficult to predict when infiltrates may occur

Note that repeated follow-up examinations are indicated not only to confirm or exclude complications but also for diagnostic purposes as it is difficult to predict when infiltrates may occur  Findings on radiographs obtained too early (within a few hours of the onset of clinical symptoms) or in a neutropenic patient may initially be negative.

Findings on radiographs obtained too early (within a few hours of the onset of clinical symptoms) or in a neutropenic patient may initially be negative.

Pathognomonic findings

Pathognomonic findings

Clinical Aspects

Typical presentation

Typical presentation

Therapeutic options

Therapeutic options

What does the clinician want to know?

What does the clinician want to know?

Extent of findings

Extent of findings  Follow-up

Follow-up  Complications.

Complications.

Differential Diagnosis

Even where history and clinical data are considered, the accuracy of diagnostic radiography in intensive care patients is only about 50%.

Even where history and clinical data are considered, the accuracy of diagnostic radiography in intensive care patients is only about 50%.

Atelectasis | – Volume loss – No constellation of infection – May be in a specific location in bedridden patients (supine) |

Aspiration pneumonia | – History – Located in the posterobasal segments – Predilection for the right side |

Pulmonary embolism or infarct | – Clinical aspects – No constellation of infection |

Atypical edema | – Patients with heart failure and pre-existing pulmonary disease (emphysema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) or pulmonary embolism can develop localized atypical edema that mimics pneumonia – Clinical findings and rapid resolution with reestablished cardiac compensation are diagnostic |

ARDS | – History and clinical findings |

Tips and Pitfalls

Reliable diagnostic findings that rule out other pathology can only be obtained by evaluating imaging data in conjunction with clinical data.

Selected References

Franquet T. Imaging of pneumonia: trends and algorithm. Eur Resp J 2001; 18: 196–208

Herold CJ, Sailer JG. Community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonias. Eur Radiol 2004; 14 (Suppl. 3): E2 – E20

Washington L, Palacio D. Imaging of bacterial pulmonary infection in the immunocompetent patient. Semin Roentgenol 2007; 42: 122–145

Opportunistic Pneumonia

Definition

Pneumonia related to pathogens in immunocompromised patients (pneumonia caused by microorganisms that occur only in patients with immune deficiency or receiving immunosuppressants but not in immunocompetent persons).

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

The spectrum of pathogens includes the bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoans that colonize the oropharynx and airways in immunocompetent persons as saprophytes without causing infection  The type and severity of the immune defect influence the spectrum of pathogens that may be expected

The type and severity of the immune defect influence the spectrum of pathogens that may be expected  The spectrum of pathogens after organ transplantation varies over time

The spectrum of pathogens after organ transplantation varies over time  In HIV–infected patients the risk of pulmonary infection depends on the number of CD4 cells: > 200/µL, bacteria; < 200/µL, Pneumocystis jirovecii, fungi, adenoviruses, RNA viruses, herpesviruses, influenza viruses; < 100/µL, cytomegalovirus, atypical mycobacteria.

In HIV–infected patients the risk of pulmonary infection depends on the number of CD4 cells: > 200/µL, bacteria; < 200/µL, Pneumocystis jirovecii, fungi, adenoviruses, RNA viruses, herpesviruses, influenza viruses; < 100/µL, cytomegalovirus, atypical mycobacteria.

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

The constellation of pathogens in neutropenia (steroid therapy, induction therapy in acute myeloid leukemia, bone marrow transplantation) includes bacteria, fungi (Aspergillus, Mucoraceae, Candida)  Pathogens in B–cell dysfunction (lymphoproliferative disorders, bone marrow transplantation, chemotherapy) include bacteria (pneumococci, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Neisseria)

Pathogens in B–cell dysfunction (lymphoproliferative disorders, bone marrow transplantation, chemotherapy) include bacteria (pneumococci, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas, Neisseria)  Pathogens in T–cell dysfunction (lymphoproliferative disorders; chemotherapy; bone marrow, stem cell, lung, heart, liver, or kidney transplantation; steroid therapy; HIV infection; infection with immunomodulatory viruses such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, varicella zoster virus) include bacteria, mycobacteria, Listeria, cryptococci, P. jirovecii and other fungi, protozoans, and viruses.

Pathogens in T–cell dysfunction (lymphoproliferative disorders; chemotherapy; bone marrow, stem cell, lung, heart, liver, or kidney transplantation; steroid therapy; HIV infection; infection with immunomodulatory viruses such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, varicella zoster virus) include bacteria, mycobacteria, Listeria, cryptococci, P. jirovecii and other fungi, protozoans, and viruses.

Imaging Signs

Modality of choice

Modality of choice

Radiographs and CT  CT is superior to conventional radiographs in terms of sensitivity and specificity and is often indicated for this reason.

CT is superior to conventional radiographs in terms of sensitivity and specificity and is often indicated for this reason.

Radiographic and CT findings

Radiographic and CT findings

These depend on the underlying disorder, risk factors, immunocompetence, and type of pathogen (see that section).

Pathognomonic findings

Pathognomonic findings

See the various forms of pneumonia.

Clinical Aspects

Typical presentation

Typical presentation

The typical constellation of findings associated with pneumonia (rise in temperature, increased blood count, abnormal C–reactive protein, physical findings) may not be present in the early stages or findings may be uncharacteristic  Symptoms depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen

Symptoms depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen  Radiographic findings represent a crucial diagnostic adjunct to immunologic and serologic studies.

Radiographic findings represent a crucial diagnostic adjunct to immunologic and serologic studies.

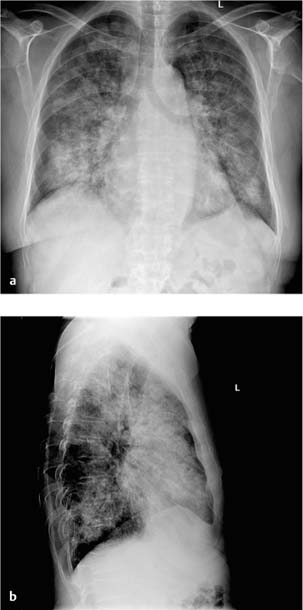

Fig. 4.3 Opportunistic pneumonia in a 53-year-old man with HIV infection (CD4 > 500/µL). The images were obtained only 2 weeks apart. The initial, not very extensive, infiltrate around the right upper lobe (a) rapidly developed into necrotizing pneumonia with abscess formation (b) as clinical findings worsened. Extensive diagnostic testing failed to identify the pathogen (Chlamydia, mycoplasmas, P. jirovecii, and mycobacteria were excluded).

Prompt treatment has a decisive influence on the prognosis.

Course and prognosis

Course and prognosis

Mortality is as high as 50% in severe cases involving respiratory or circulatory insufficiency, extent, or rapid progression.

What does the clinician want to know?

What does the clinician want to know?

Confirmation of a tentative diagnosis of pneumonia  Extent of findings

Extent of findings  Follow-up

Follow-up  Complications

Complications  Narrow down the spectrum of possible pathogens.

Narrow down the spectrum of possible pathogens.

Differential Diagnosis

Experience and knowledge of the type and severity of the immune defect are crucial in narrowing down the spectrum of possible pathogens  Specific constellations of radiographic findings provide useful diagnostic information in this context (this applies especially to pulmonary mycosis and mycobacterial infection)

Specific constellations of radiographic findings provide useful diagnostic information in this context (this applies especially to pulmonary mycosis and mycobacterial infection)  However, mixed forms are common.

However, mixed forms are common.

Extrapulmonary infections | – Infections of the gastrointestinal tract, urinary tract, paranasal sinuses, and central nervous system must be excluded |

Edema, hemorrhage, infarct, ARDS, etc. | – Reliable differential diagnosis is not possible without clinical information |

Tips and Pitfalls

When interpreted in conjunction with clinical data, findings are usually suggestive  Where such data are unavailable, it will not be possible to reliably distinguish pneumonia from other pathology.

Where such data are unavailable, it will not be possible to reliably distinguish pneumonia from other pathology.

Selected References

Franquet T. Imaging of pneumonia: trends and algorithm. Eur Resp J 2001; 18: 196–208

Gharib AM, Stern EJ. Radiology of pneumonia. Med Clin North Am 2001; 85: 1461–1491

Tuengerthal S. [Radiologie der opportunistischen Pneumonien.] Radiologe 2005; 45: 373–384 [In German]

Lobar Pneumonia

Definition

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

A fundamental distinction should be drawn between community-acquired and hospital-acquired (nosocomial) pneumonias as different spectra of pathogens must be considered  Typical pathogens in lobar pneumonia include pneumococci, Klebsiella, and Proteus

Typical pathogens in lobar pneumonia include pneumococci, Klebsiella, and Proteus  Mycoplasmas and Legionella can produce a similar picture.

Mycoplasmas and Legionella can produce a similar picture.

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

The disorder develops in the distal air spaces where gas exchange occurs  It progresses in pathoanatomic stages: Red hepatization with an erthyrocytic exudate

It progresses in pathoanatomic stages: Red hepatization with an erthyrocytic exudate  Gray hepatization with influx of leukocytes

Gray hepatization with influx of leukocytes  Yellow hepatization with proteolytic breakdown of the exudate.

Yellow hepatization with proteolytic breakdown of the exudate.

Imaging Signs

Modality of choice

Modality of choice

Radiographs  CT is indicated only where findings are equivocal or there is clinical suspicion but no radiographic correlate.

CT is indicated only where findings are equivocal or there is clinical suspicion but no radiographic correlate.

Radiographic findings

Radiographic findings

Homogeneous, nonsegmental area of opacification with a pleural interface consistent with initial manifestation in the distal air spaces  Air bronchogram

Air bronchogram  Lobar borders are intact

Lobar borders are intact  Usually there is no volume change, although expansion may occur (“bulging fissure” sign)

Usually there is no volume change, although expansion may occur (“bulging fissure” sign)  Findings and course depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

Findings and course depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

CT findings

CT findings

Findings are similar to radiography  CT is more sensitive in detecting associated findings (multifocal manifestation, pleuritis, liquefaction).

CT is more sensitive in detecting associated findings (multifocal manifestation, pleuritis, liquefaction).

Pathognomonic findings

Pathognomonic findings

See “Radiographic findings.”

Clinical Aspects

Typical presentation

Typical presentation

Antibiotics have made the typical clinical picture (acute onset with chills, fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, cough with rusty brown sputum, chest pain, and very poor general health) less common  Blood count shows leukocytosis with left

Blood count shows leukocytosis with left  Manifestation and course of the pneumonia depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

Manifestation and course of the pneumonia depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

Therapeutic options

Therapeutic options

Antibiotics  In hospital-acquired infections in particular an antibiotic sensitivity study to isolate the pathogen is indicated.

In hospital-acquired infections in particular an antibiotic sensitivity study to isolate the pathogen is indicated.

Course and prognosis

Course and prognosis

Uncomplicated disease resolves completely although this can take weeks to months  Possible complications include pulmonary abscess, empyema, and septic embolism.

Possible complications include pulmonary abscess, empyema, and septic embolism.

Fig. 4.4 Lobar pneumonia. The plain chest radiographs show two homogeneous areas of infiltrate with broad pleural contact in the posterior right upper lobe and right middle lobe. Associated with it is a slight pneumothorax with fluid accumulation.

What does the clinician want to know?

What does the clinician want to know?

Confirmation of a tentative diagnosis of pneumonia  Degree of severity

Degree of severity  Complicating findings

Complicating findings  Follow-up

Follow-up  Only rarely will the radiologist be asked to narrow the spectrum of possible pathogens as the treatment of acute community-acquired pneumonia is empirical and does not require identification of a specific pathogen.

Only rarely will the radiologist be asked to narrow the spectrum of possible pathogens as the treatment of acute community-acquired pneumonia is empirical and does not require identification of a specific pathogen.

Differential Diagnosis

Morphologic findings on the radiograph alone do not provide evidence of a specific pathogen; at best they can be used to differentiate between bacterial and viral pneumonia  Correlation of imaging findings with history and clinical data is essential for the diagnosis

Correlation of imaging findings with history and clinical data is essential for the diagnosis  Experience is a useful guide: viral infections are most common in children, mycoplasma pneumonia in adolescents, and bacterial pneumonia in adults.

Experience is a useful guide: viral infections are most common in children, mycoplasma pneumonia in adolescents, and bacterial pneumonia in adults.

Pulmonary embolism or infarct | – Clinical aspects – No constellation of infection |

Bronchial carcinoma with poststenotic pneumonia | – CT and bronchoscopy are indicated where clinical or radiographic findings suggest such a lesion (findings refractive to treatment or recurring at the same location) |

Atypical edema | – Patients with left heart failure can develop localized atypical edema that mimics pneumonia – Clinical findings and rapid resolution with reestablished cardiac compensation are diagnostic |

Tips and Pitfalls

When interpreted in conjunction with clinical data, findings are usually suggestive  The differentiation between lobar pneumonia, bronchopneumonia, and interstitial pneumonia is not always helpful as the same pathogen can produce widely varying pictures.

The differentiation between lobar pneumonia, bronchopneumonia, and interstitial pneumonia is not always helpful as the same pathogen can produce widely varying pictures.

Selected References

Franquet T. Imaging of pneumonia: trends and algorithm. Eur Resp J 2001; 18: 196–208

Herold CJ, Sailer JG. Community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonias. Eur Radiol 2004; 14 (Suppl. 3): E2 – E20

Washington L, Palacio D. Imaging of bacterial pulmonary infection in the immunocompetent patient. Semin Roentgenol 2007; 42: 122–145

Bronchopneumonia

Definition

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

A fundamental distinction should be made between community-acquired and hospital-acquired (nosocomial) pneumonias as different pathogens must be considered  Typical pathogens include staphylococci, streptococci, Pseudomonas, and anaerobes

Typical pathogens include staphylococci, streptococci, Pseudomonas, and anaerobes  Haemophilus, mycoplasmas, and viruses can produce a similar picture.

Haemophilus, mycoplasmas, and viruses can produce a similar picture.

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

The infection begins in the bronchioles (often secondary to viral infection of the upper respiratory tract) and spreads to the peribronchial alveoli  The disease does not progress in stages, rather findings include the simultaneous presence of acute and resolving infiltrates.

The disease does not progress in stages, rather findings include the simultaneous presence of acute and resolving infiltrates.

Imaging Signs

Modality of choice

Modality of choice

Radiographs  CT is indicated only where findings are equivocal or there is clinical suspicion but no radiographic correlate.

CT is indicated only where findings are equivocal or there is clinical suspicion but no radiographic correlate.

Radiographic findings

Radiographic findings

Ill-defined, heterogeneous infiltrates often showing a focal pattern  Segmental configuration

Segmental configuration  An air bronchogram is usually absent

An air bronchogram is usually absent  Mucus obstruction of the airways produces subsegmental atelectasis, leading to volume loss

Mucus obstruction of the airways produces subsegmental atelectasis, leading to volume loss  Abscesses

Abscesses  Findings and course depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

Findings and course depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

CT findings

CT findings

Findings are similar to radiography  CT is more sensitive in detecting associated findings (multifocal manifestation, pleuritis, liquefaction).

CT is more sensitive in detecting associated findings (multifocal manifestation, pleuritis, liquefaction).

Pathognomonic findings

Pathognomonic findings

See “Radiographic findings.”

Clinical Aspects

Typical presentation

Typical presentation

Subacute onset  Slowly increasing fever

Slowly increasing fever  Productive cough with mucopurulent sputum

Productive cough with mucopurulent sputum  Status of general health varies and may be only slightly impaired

Status of general health varies and may be only slightly impaired  Manifestation and course of the pneumonia depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

Manifestation and course of the pneumonia depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

Therapeutic options

Therapeutic options

Antibiotics  In hospital-acquired infections in particular an antibiotic sensitivity study to isolate the pathogen is indicated.

In hospital-acquired infections in particular an antibiotic sensitivity study to isolate the pathogen is indicated.

Course and prognosis

Course and prognosis

Uncomplicated cases have a good prognosis  Parenchymal necrosis results in residual scarring.

Parenchymal necrosis results in residual scarring.

What does the clinician want to know?

What does the clinician want to know?

Confirmation of a tentative diagnosis of pneumonia  Narrow down the spectrum of possible pathogens.

Narrow down the spectrum of possible pathogens.

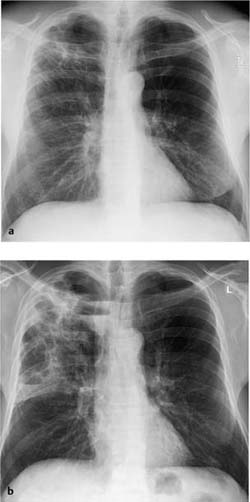

Fig. 4.5 Bronchopneumonia in a 17-year-old boy. The plain chest radiograph shows focal confluent infiltrates in the lower left lung field.

Differential Diagnosis

Morphologic findings on the radiograph alone do not provide evidence of a specific pathogen; at best they can be used to differentiate between bacterial and viral pneumonia  Correlation of imaging findings with history and clinical data is essential to the diagnosis

Correlation of imaging findings with history and clinical data is essential to the diagnosis  Experience is a useful guide: viral infections are most common in children, mycoplasma pneumonia in adolescents, and bacterial pneumonia in adults.

Experience is a useful guide: viral infections are most common in children, mycoplasma pneumonia in adolescents, and bacterial pneumonia in adults.

Lobar pneumonia, interstitial pneumonia | – Confluent lesions in bronchopneumonia can mimic lobar pneumonia – The differentiation between lobar pneumonia, bronchopneumonia, and interstitial pneumonia is not always helpful as the same pathogen can produce widely varying pictures |

Tips and Pitfalls

When interpreted in conjunction with clinical data, findings are usually suggestive.

Selected References

Franquet T. Imaging of pneumonia: trends and algorithm. Eur Resp J 2001; 18: 196–208

Herold CJ, Sailer JG. Community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonias. Eur Radiol 2004; 14 (Suppl. 3):E2–E20

Washington L, Palacio D. Imaging of bacterial pulmonary infection in the immunocompetent patient. Semin Roentgenol 2007; 42: 122–145

Interstitial Pneumonia and Atypical Pneumonia

Definition

The term “atypical pneumonia” was, in the past, used to describe pneumonias with atypical clinical, laboratory, and radiologic findings  Today the term is applied to pneumonias in which the pathogen is difficult to isolate.

Today the term is applied to pneumonias in which the pathogen is difficult to isolate.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

Affected patients include those with chronic wasting diseases, those on long-term antibiotic therapy, or those with primary or secondary immunodeficiency (cyto-static agents, immunosuppressives)  Typical pathogens include Pneumocystis jirovecii, viruses, fungi, chlamydiae, and rickettsiae.

Typical pathogens include Pneumocystis jirovecii, viruses, fungi, chlamydiae, and rickettsiae.

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Nonbacterial pneumonia  Infection develops in and is largely limited to the interstitium with minimal involvement of the alveolar parenchyma, i.e., with minimal mixed interstitial-alveolar infiltrates

Infection develops in and is largely limited to the interstitium with minimal involvement of the alveolar parenchyma, i.e., with minimal mixed interstitial-alveolar infiltrates  Capillary damage leads to hemorrhagic interstitial and/or alveolar edema.

Capillary damage leads to hemorrhagic interstitial and/or alveolar edema.

Imaging Signs

Modality of choice

Modality of choice

Radiographs  CT is indicated only where findings are equivocal or there is clinical suspicion but no radiographic correlate.

CT is indicated only where findings are equivocal or there is clinical suspicion but no radiographic correlate.

Radiographic and CT findings

Radiographic and CT findings

Bilateral symmetric linear, reticular, or reticulonodular opacities and/or ground-glass opacities  Often there is mixed interstitial-alveolar shadowing

Often there is mixed interstitial-alveolar shadowing  Findings and course depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

Findings and course depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

Pathognomonic findings

Pathognomonic findings

See radiographic and CT findings.

Clinical Aspects

Typical presentation

Typical presentation

Insidious onset with moderate fever without chills, nonproductive cough, flulike headache and joint pain  Blood count shows slight leukocytosis with relative lymphocytosis

Blood count shows slight leukocytosis with relative lymphocytosis  Clinical findings and course depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

Clinical findings and course depend on the individual patient’s immunocompetence and the virulence of the pathogen.

Therapeutic options

Therapeutic options

The pathogen must be isolated to permit specific therapy  Where indicated, immunocompetence should be improved by treating the underlying disorder.

Where indicated, immunocompetence should be improved by treating the underlying disorder.

Course and prognosis

Course and prognosis

With effective therapy the disease resolves completely.

What does the clinician want to know?

What does the clinician want to know?

Confirmation of a tentative diagnosis of pneumonia and characterization.

a The plain chest radiograph shows interstitial shadowing limited primarily to the mid-lung with secondary opacity and masking of vascular structures.

b

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Course and prognosis

Course and prognosis

Therapeutic options

Therapeutic options