Type of gastritis

Etiological factors

Gastritis synonyms

Nonatrophic

H. pylori

Superficial

?Other factors

Diffuse antral gastritis (DAG)

Chronic antral gastritis (CAG)

Interstitial-follicular

Hypersecretory

Type Ba

Atrophic

Autoimmune

Autoimmunity

Type Aa

Diffuse corporal

Pernicious anemia associated

Multifocal atrophic

H. pylori

Type Ba, type ABa

Dietary

Environmental

?Environmental factors

Metaplastic

Special forms

Chemicalb

Chemical irritation

Reactive

Bile

Reflux

NSAIDs

NSAID

?Other agents

Type Ca

Radiation

Radiation injury

Lymphocytic

?Idiopathic immune mechanisms

Varioliform(endoscopic)

Gluten

Celiac disease associated

Drug (ticlopidine)

?H. pylori

Noninfectious granulomatous

Crohn’s disease

Sarcoidosis

Wegener’s granulomatosis and other vasculitides

Foreign substances

Idiopathic

Isolated granulomatous

Eosinophilic

Food sensitivity

Allergic

?Other allergens

Other infectious

Bacteria (other than H. pylori)

Phlegmonous

Viruses

Fungi

Parasites

Well-performed barium studies make it possible to detect and characterize gastritis and gastric ulcers. Barium studies should include double-contrast views with a high-density barium suspension, prone or upright compression views with a low-density barium suspension, and flow technique. Even though gastric thickening on computed tomography (CT) is often nonspecific and shows poor correlation with symptoms of the patient, tailored multidetector-row CT (MDCT) is useful in the evaluation of gastritis and gastric ulcers and their complications. Recently, MDCT has provided three-dimensional virtual gastroscopy (VG) that makes it possible to evaluate gastric morphology in detail like a double-contrast barium study or optical endoscopy (Chen et al. 2009).

5.1 Gastritis

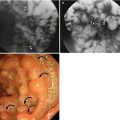

5.1.1 Erosive Gastritis

The most characteristic feature of erosive gastritis is erosions. Erosion is defined as the mucosal break which does not penetrate beyond the muscularis mucosa. Aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are considered to be the most common cause of erosive gastritis, accounting for about 50 % of cases (Levine 2008b). Other common causes of erosions are alcohol, steroids, stress, trauma, burns, viral or fungal infections, and reflux of bile or pancreatic secretions. The reported radiologic prevalence of erosive gastritis is 0.5–26 % (Chen et al. 2001). Two types of erosions, complete forms or varioliform and incomplete or flat forms, may be seen on double-contrast studies. Complete or varioliform erosions are manifested as punctate or slit-like barium collections surrounded by radiolucent halos of edematous elevated mucosa on barium studies, which show up in most patients (Levine 2008b). Complete erosions are typically noted in the gastric antrum and are often aligned on antral folds (Levine 2008b). Sometimes, NSAIDs produce incomplete or linear erosions in the body or near the greater curvature of the stomach, because the dissolving tablets responsible for localized mucosal injury collect, by gravity, in the dependent portion of the stomach (Levine 2008b). If the erosion is subtle or healed, it might appear as nodular filling defects or scalloped antral folds (Chen et al. 2001). Incomplete or “flat” erosions appear as mucosal defects without elevation of the surrounding mucosa. They are shown as linear streaks or dots of barium, which are much more difficult to detect than complete erosions, accounting for only 5–19 % of all erosions diagnosed on barium studies (Levine 2008b). Gastric erosions can sometimes be mistaken for aphthoid ulcers of Crohn’s disease or “bull’s-eye” lesions on double-contrast studies (Levine 2008b).

5.1.2 H. pylori Gastritis

H. pylori gastritis can be diagnosed if the organisms are identified histologically in the endoscopic biopsy specimens. H. pylori, the cause of acute or chronic gastritis, is a gram-negative bacillus which is clustered under the mucus layer on surface epithelium or superficial foveolar cells in the stomach (Dixon et al. 1996; Levine 2008b). The prevalence of H. pylori is age related; 24 % of the population 20–39 years of age and 82 % of the population 60 years of age and older are infected by this organism (Chen et al. 2001). Noninvasive tests of high sensitivity and specificity (>90 %) such as the urea breath test (using oral 14C-labeled or 13C-labeled urea) and serologic tests are available for diagnosis of H. pylori gastritis (Levine 2008b). H. pylori gastritis typically involves the antrum of the stomach; however, the proximal portion of the stomach or even the entire stomach may be involved. The most common finding on barium studies is diffuse or localized thickened folds in the gastric antrum or body (Levine 2008b). Other possible findings are an irregular contour of the lesser curvature, ulcers, nodularity, enlarged areae gastricae, polyps, luminal narrowing, and spasms. Antral erosion may also be noted, but rarely associated (Levine 2008b; Chen et al. 2001; Dheer et al. 2002). If lymphoid hyperplasia is noted on double-contrast barium studies in patients with chronic H. pylori gastritis, the possibility of low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma should be considered.

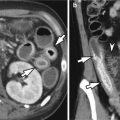

5.1.3 Chronic Gastritis

Chronic gastritis is a multifactorial disorder which shows chronic inflammation and atrophy caused by ongoing injury to the gastric mucosa. Up to now there has been some confusion in the classification of chronic gastritis as there have been several terms that have been applied synonymously for it: superficial, atrophic, and antral gastritis. Chronic gastritis can be classified based on topography, morphology, and etiology by the revised Sydney System classification (Dixon et al. 1996). It is separated into chronic nonatrophic gastritis and chronic atrophic gastritis based on the presence or absence of atrophy. Chronic atrophic gastritis may be classified into type A (autoimmune) and type B (non-autoimmune) according to topographical distribution of atrophy. Type A gastritis affects the fundus and may extend to the gastric body. Antibodies against parietal cells cause atrophy of the gastric mucosa, resulting in the problem on absorption of B12 followed clinically by pernicious anemia. In these patients, the risk for the development of gastric carcinoma increases three times more than in the general population (Levine 2008b). Radiologic findings would normally show in mild atrophic change. With more advanced atrophic change, characteristic features are a smooth, featureless mucosa and decreased or absent gastric folds, mainly in the upper stomach (“bald fundus”). The contour of the stomach may become more tubular, with a distended fundus (“H-bomb sign”). Because of the loss of parietal cells, areae gastricae may be reduced in number and size (Chen et al. 2001; Rubesin et al. 2008). Type B gastritis is more common than type A gastritis. In type B gastritis, multifocal atrophies involve the gastric antrum with limited involvement of the fundus and body. The most common cause is H. pylori infection, but extrinsic causes, such as alcohol or reflux of bile, NSAIDs, and dietary injury, could also cause type B atrophic gastritis. These factors may induce multifocal atrophy, independently of or synergistically with H. pylori (Dixon et al. 1996). Loss of glandular cells leads to thinning of the mucosal layer which results in erosion or ulceration of the mucosa. Finally, fibrous replacement or a collapse of the existing supporting matrix may occur. Atrophy in the oxyntic mucosa is closely related to the decrease of acid secretion and usually associated with intestinal metaplasia (Dixon et al. 1996). Intestinal metaplasia is associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer (Dixon et al. 1996). Atrophy could be present in the absence of intestinal metaplasia (Dixon et al. 1996). Multifocal atrophies are often patchy and macroscopically flat, so that it is difficult to recognize on barium studies (Rubesin et al. 2008). Focal enlargement of the areae gastricae or irregular nodules disrupting the smooth surface of gastric mucosa may be caused by inflammation, metaplasia, or a malignant tumor such as superficial spreading carcinoma (Levine 2008b; Chen et al. 2001; Rubesin et al. 2008).

5.1.4 Hypertrophic Gastritis

Hypertrophic gastritis is characterized by marked glandular hyperplasia and increased secretion of acid in the stomach (Levine 2008b). Edema and inflammation of the gastric wall also contribute to thickening of rugal folds. Even though the pathogenesis of this condition is uncertain, gastric glandular hyperplasia may be caused by pituitary, hypothalamic, or vagal stimuli (Levine 2008b). Barium studies may reveal thickened folds, predominantly in the gastric fundus and body, because the acid-secreting portion of the stomach is most affected by this condition. Poor mucosal coating with fluid-fluid level would also be shown as acid secretion is increased (Chen et al. 2001).

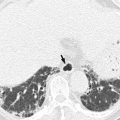

5.1.5 Emphysematous Gastritis

Emphysematous gastritis is a fatal rare type of phlegmonous gastritis in which infection by gas-forming organisms such as Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, Clostridium perfringens, and Staphylococcus aureus causes gas in the gastric wall (Levine 2008b). This condition usually occurs in cases of serious insults to the stomach, such as gastroduodenal surgery, caustic ingestion, or gastric volvulus. Ischemia or necrosis allows gas-forming organisms to enter the gastric wall. Even with intensive treatment, mortality rates as high as 60 % have been reported (Levine 2008b). Emphysematous gastritis should be differentiated from other rare conditions known as gastric emphysema in which gas is thought to enter the gastric wall through mucosal tears which might be caused by increased intraluminal pressure associated with a gastric outlet obstruction or by iatrogenic injury resulting from endoscopy or other gastric instrumentation. This condition is more common than emphysematous gastritis in clinical practice and tends to resolve spontaneously, and patients are asymptomatic (Horton and Fishman 2003).

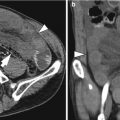

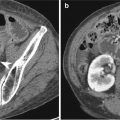

Gastritis is manifested as circumferential or focal thickening of the gastric wall which sometimes simulates a gastric carcinoma. Decreased wall attenuation with hyperemic mucosal lining due to edema and inflammation suggests benign thickening on contrast-enhanced CT (Horton and Fishman 2003). Loss of gastric wall stratification on CT may suggest the possibility of malignancy (Chen et al. 2010). In contrast to other benign gastric disease, emphysematous gastritis reveals specific radiologic findings such as multiple streaks, bubbles, or mottled collections of gas in the wall of the stomach on abdominal radiographs and CT (Cruz et al. 1992).

5.2 Benign Gastric Ulcer

The major causative factor in the development of both gastric and duodenal ulcers is H. pylori. In various studies, the reported prevalence of H. pylori gastritis has ranged from 60 to 80 % in patients with gastric ulcers and from 95 to 100 % in patients with duodenal ulcers (Levine 2008a). Other possible causative agents include NSAIDs, corticosteroids, tobacco, alcohol, coffee, stress, duodenogastric reflux of bile, and delayed gastric emptying. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is also one of the causes of gastric ulcers. There are several characteristic features of benign gastric ulcers on barium studies (Levine 2008a): round or ovoid collections of barium on the lesser curvature or posterior wall of the antrum or body of the stomach, which may project beyond the contour of the adjacent gastric wall in profile view; distorted enlarged areae gastricae in the region of the ulcer because of edema and inflammation of the adjacent mucosa; smooth, symmetric radiating folds on the edge of the ulcer crater because of retraction of the gastric wall adjacent to ulcers; a thin, barely perceptible radiolucent line (Hampton’s line) reflecting undermining of the mucosa surrounding the orifice of the ulcer crater, which separates barium in the ulcer crater from barium in the gastric lumen; a wide, radiolucent band (ulcer collar) reflecting more edematous change of the rim of the undermined mucosa; and an ulcer mound reflecting severe edema and inflammation surrounding the ulcer, which appears as a smooth, bilobed hemispheric mass projecting into the lumen on both sides of the ulcer. Occasionally, an incisura on the greater curvature may be shown because of an ulcer-related retraction of the opposite wall. A linear crater may reflect a gastric ulcer in a healing stage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree