14 Inflammatory Diseases

Infections

Diskitis

Frequency: rare without involvement of the adjacent vertebral bodies; 0.2–4% following nucleotomy (depending on the series).

Suggestive morphologic findings: decreased density of the affected disk with a paravertebral soft-tissue reaction. Contrast enhancement is possible, but not obligatory.

Procedure: computed tomography (CT) scans parallel to the disk spaces, contrast administration.

Other studies: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the method of choice for detecting edema and contrast enhancement, especially in children.

Checklist for scan interpretation:

Determine the precise level of the affected disk.

Determine the precise level of the affected disk.

Extent of the surrounding reaction?

Extent of the surrounding reaction?

Inflammatory soft-tissue tumor creating an intraspinal mass?

Inflammatory soft-tissue tumor creating an intraspinal mass?

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Diskitis is based on a rare primary infection of the nucleus pulposus with possible secondary involvement of the adjacent endplates and vertebral bodies. It may result from an invasive procedure such as herniated disk surgery, lumbar puncture, myelography, or chemonucleolysis, but spontaneous occurrence is more common.

Spontaneous bacterial diskitis is primarily a pediatric condition. The disk space becomes infected by the hematogenous route through vessels, still present in children, that penetrate the endplates to supply the nucleus pulposus. These vessels become obliterated with aging and usually disappear by age 20.

Frequency

Frequency

Isolated spontaneous diskitis that does not involve the adjacent vertebral bodies and soft tissues is rare. It typically occurs in childhood, with peaks at 6 months to 4 years and at 10–14 years. The L3–4 and L4–5 levels are most commonly affected, and disk space infection above T8 is rare. Postoperative diskitis occurs in approximately 0.2–4% of patients who have undergone a nucleotomy, depending on the series.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical Manifestations

Patients with spontaneous diskitis complain mostly of local pain that is aggravated by movement and often has a radicular distribution. In children too young to verbalize their symptoms, a refusal to walk and, later, to sit upright usually brings the child to the attention of a physician. Only about 30% of affected patients are febrile. Postinterventional diskitis usually presents clinically after a symptom-free interval of 1–4 weeks (3 days to 8 months). Typical features at that time are fever, localized pain in the affected segment, radicular pain, and laboratory signs of inflammation.

CT Morphology

CT Morphology

CT sometimes shows decreased density at the affected level. Usually, there is an accompanying reaction of adjacent paravertebral soft tissues or even of intraspinal tissues, which may cause indentation of the dural sac. Contrast enhancement may occur but is not obligatory.

The following CT findings are pathognomonic for diskitis:

• Fragmentation of the endplates

• Paravertebral soft-tissue swelling that obliterates the intervening fat planes

• Paravertebral abscess

If only the first two criteria are present, the specificity is still 87%.

Spondylodiskitis

Frequency: a tuberculous etiology is rare but has been showing an upward trend. Postinterventional spondylodiskitis can occur in patients with a corresponding history and clinical presentation.

Suggestive morphologic findings: contiguous involvement of a disk space and the adjacent vertebral bodies with bone destruction, a paravertebral soft-tissue mass, disk space narrowing, and intense contrast enhancement.

Procedure: contiguous thin CT slices with secondary reconstructions after intravenous contrast administration.

Other studies: MRI is particularly useful for followup. Plain films, myelography, and postmyelographic CT can define the extent of dural sac compression by an intraspinal soft-tissue mass.

Checklist for scan interpretation:

Determine the precise location of the affected level.

Determine the precise location of the affected level.

Extent of the surrounding reaction?

Extent of the surrounding reaction?

Inflammatory soft-tissue mass causing an intraspinal mass effect?

Inflammatory soft-tissue mass causing an intraspinal mass effect?

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Spondylodiskitis refers to a combined infection of the disk space and one or both adjacent vertebrae. It is the most common form of inflammatory spinal disease encountered in adults. Two main types are distinguished based on etiology and causative agent:

• Spontaneous or postinterventional spondylodiskitis.

• Tuberculous (specific) and nontuberculous spondylodiskitis.

Spontaneous form. The spontaneous form of spondylodiskitis, like epidural abscess, most commonly results from the hematogenous spread of infection, often from pelvic organs. Infectious organisms can spread from that region to the spine through venous channels such as the ascending lumbar veins, which anastomose with draining veins from the vertebral bodies and from the epidural venous plexus. Infection is usually initiated in the anterior portions of the vertebral bodies near the endplates; from there it can spread to the intervertebral disk space and adjacent vertebral bodies by contiguous extension or by further hematogenous spread. The most common causative organism is Staphylococcus aureus.

Tuberculous spondylodiskitis (Figs. 14.1, 14.2). Ten percent of tuberculosis patients suffer bone and joint involvement. Fifty percent of these patients develop tuberculous spondylodiskitis, and half of these have a history of active pulmonary tuberculosis with hematogenous spread of infection to a disk space and the adjacent vertebral bodies. The resulting destruction most commonly involves the anterior two-thirds of the vertebral body and spares the posterior elements. There is a progressive loss of disk height over time, although the disk space usually remains intact for a longer period than in acute infections with Staphylococcus aureus. A conspicuous paraspinal soft-tissue mass frequently develops and is often associated with an abscess, usually sterile, that may show anterior or occasional posterior subligamentous extension over several segments.

Frequency

Frequency

Tuberculous spondylodiskitis is a rare condition that has become more common in recent years, due to the rising worldwide incidence of tuberculous diseases and the growing prevalence of multiresistant mycobacterial strains. Moreover, recent publications show that the risk of contracting tuberculosis is approximately 80 times higher in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and 170 times higher in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) than in the uninfected population. This is another factor that may lead to increased case numbers of tuberculous spondylodiskitis.

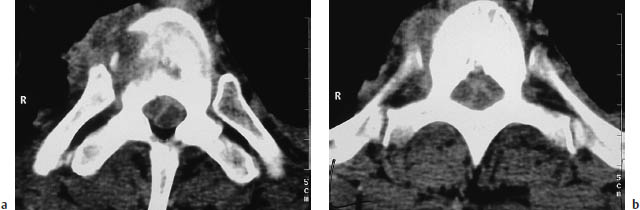

Fig. 14.2 a, b Tuberculous spondylodiskitis. Pathologic specimens (courtesy of the Department of Pathology, Charité Hospital, Berlin).

The peak age incidence of the disease has been rising in recent decades from 20–30 years to 30–40 years in industrialized countries. The average latent period between bacterial colonization and overt clinical infection is 4.3 months in the cervical spine, 9.8 months in the upper thoracic spine, 17.3 months in the lower thoracic spine, and 20.7 months in the lumbar spine.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical Manifestations

Most patients have local spontaneous pain, pain on percussion of the affected area, or pain on axial compression of the spine. The pain may be aggravated by movement, and may show a radicular distribution. Only about 30% of patients are febrile.

CT Morphology

CT Morphology

CT shows contiguous involvement of a disk space and both adjacent vertebral bodies with bone destruction, a paravertebral soft-tissue mass, and a loss of disk height, which is less pronounced in tuberculous spondylodiskitis than in cases caused by Staphylococcus aureus. The affected level always shows intense enhancement after intravenous contrast administration.

Because of hematogenous spread from infected pulmonary foci, tuberculous spondylodiskitis more commonly affects the upper spinal segments, especially the thoracic spine, than the nontuberculous bacterial forms.

The inflammatory tissue usually enhances intensely after contrast administration, sparing areas of necrotic liquefaction.

Postinterventional spondylodiskitis usually presents clinically after an asymptomatic interval of 1–4 weeks (3 days to 8 months). Typical features at that time are fever, localized pain in the affected segment, radicular pain, and laboratory signs of inflammation.

• ESR < 50 mm/h |

• History = 12 months |

• Insidious course (usually afebrile or subfebrile) |

• More than three vertebral bodies affected |

• ESR = 100 mm/h |

• History < 3 months |

• Rapid course with fever = 39 °C |

• Patient less than 14 years of age |

• Negative tuberculin skin test |

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of tuberculous and nontuberculous spondylodiskitis is outlined in Tables 14.1 and 14.2.

Spondylitis, Vertebral Osteomyelitis

Frequency: rarely seen in isolation; usually occurs in the setting of spondylodiskitis, or in association with an epidural abscess.

Suggestive morphologic findings: hypodensity of the affected portions of the vertebral body and/or adjacent disk space. Possible paravertebral soft-tissue mass with dural sac compression. Nonnecrotic areas enhance after contrast administration.

Procedure: thin contiguous CT slices, secondary reconstructions, contrast administration.

Other studies: MRI (high sensitivity and specificity, good spatial resolution) is particularly recommended for follow-up.

Checklist for scan interpretation:

Intraspinal soft-tissue mass?

Intraspinal soft-tissue mass?

Extent of vertebral body destruction? Potential instability?

Extent of vertebral body destruction? Potential instability?

Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Circumscribed osteomyelitis of a vertebral body is relatively rare, and occurs predominantly in the following high-risk groups:

• Intravenous drug abusers

• Patients with diabetes mellitus

• Patients on hemodialysis

• Elderly patients with no other apparent risk factors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree