Chapter 7 Interstitial Lung Disease

Many chronic diseases can produce diffuse opacities in the lung. Some are primarily lung disorders, and some others are manifestations of diseases arising elsewhere. Although these disorders have frequently been referred to as interstitial lung diseases, many also involve the alveolar spaces. More than 150 such disorders have been described, and a comprehensive list is provided in Box 7-1. Despite the large number, approximately 15 to 20 constitute 90% of such disease states, and these are the entities that are discussed in this chapter. Pneumoconioses and vascular disorders are discussed in Chapters 8 and 9.

Box 7-1 Diffuse Interstitial (Parenchymal) Lung Diseases

IMMUNOLOGIC AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISORDERS

Progressive systemic sclerosis

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia

Idiopathic pulmonary hemorrhage

IDIOPATHIC INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIAS

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia

Respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease

Pneumonia resulting from irradiation

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients usually present (Box 7-2) with dyspnea as the predominant symptom. Physical examination frequently finds only dry rales or crackles. Physiologically, the abnormalities primarily affect gas exchange and result in hypoxemia. Reduced lung volumes may result in a restrictive pattern identified on pulmonary function tests.

PATTERN RECOGNITION

Classification

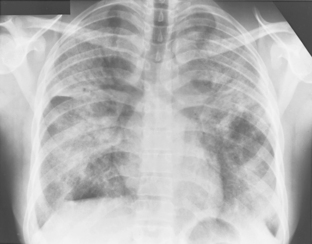

A graphic or morphometric classification is a better approach and is enumerated in Box 7-3. The patterns are described as nodular, irregular or linear, cystic, ground-glass, and parenchymal consolidation. Most patterns can be readily identified on standard radiographs, but ground-glass and cystic disease patterns are much more readily appreciated on HRCT. Many diseases demonstrate more than one pattern (see Box 7-3).

Box 7-3 Patterns of Opacities in Interstitial Lung Disease

LINEAR PATTERN (SMALL, IRREGULAR, RETICULAR OPACITIES)

Usual interstitial pneumonitis (idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis)*

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis

Fibrosis associated with collagen vascular disease

GROUND-GLASS ATTENUATION

Acute interstitial pneumonitis

Desquamative interstitial pneumonitis

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis

PARENCHYMAL CONSOLIDATION (AIRSPACE OR ALVEOLAR DISEASE)

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia

Pattern Characteristics

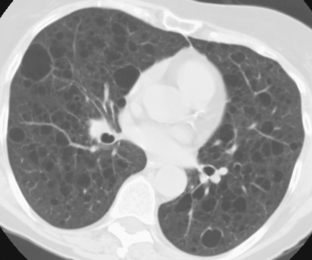

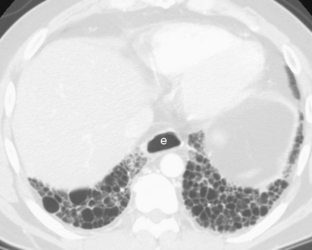

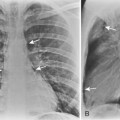

The nodular pattern (Fig. 7-1) is composed of multiple, small nodules that range from 1 mm to 1 cm in diameter. Irregular linear opacities (Fig. 7-2) frequently form a reticular pattern that may be fine or coarse. There are two types of cystic patterns: thin-walled cysts (Fig. 7-3) and honeycombing. Honeycomb spaces usually are 1 cm or less in diameter with relatively thick walls (>2 mm), and they are a pathologic correlate of end-stage lung disease with fibrosis (Fig. 7-4). Ground-glass attenuation is a term used almost exclusively with CT. It consists of an amorphous opacification or increase in attenuation, which is mildly severe and is not sufficient to obliterate the pulmonary vessels. Parenchymal consolidation, which has been referred to as alveolar or airspace disease, is characterized by dense opacification often with air bronchograms (Fig. 7-5). This opacification obliterates the pulmonary vasculature. Septal lines are a common feature of many interstitial lung disorders but are particularly predominant in lymphangitic spread of carcinoma and in congestive heart failure.

Zonal Distribution

Diseases have zonal preferences in the lungs (Box 7-4), although severe diseases often become diffuse. For example, histiocytosis, sarcoidosis, silicosis, and coal worker’s pneumoconiosis typically favor the upper lobes, whereas idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and fibrosis associated with collagen vascular disease tend to be a lower-zone phenomenon. Pleural disease may take one of several forms (Box 7-5). Pneumothorax may be seen as a complication of any cause of end-stage lung, but it may be identified early in the course of diseases such as histiocytosis X and lymphangioleiomyomatosis, in which there is a high prevalence of pneumothorax. Similarly, pleural effusions and diffuse thickening are often associated with collagen vascular disease and asbestos exposure. Pleural plaques, an uncommon feature, are produced almost exclusively by asbestos exposure. Adenopathy (Box 7-6), which is recognized on standard radiographs, is associated with silicosis and sarcoidosis, lymphangitic carcinomatosis, and lymphoma. CT is more sensitive in the identification of adenopathy and may demonstrate mildly enlarged lymph nodes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, fibrosis associated with the collagen vascular diseases, and lymphangioleiomyomatosis.

Box 7-4 Zonal Preference

Box 7-6 Adenopathy

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY*

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis

Fibrosis associated with collagen vascular disease

The size of the lung (i.e., lung volumes) may be a clue to the differential diagnosis (Box 7-7). The fibrotic disorders are characterized by marked restriction, and small lungs invariably are seen in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and related disorders. However, histiocytosis X and sarcoidosis in the early stages are usually associated with normal lung volumes, but lymphangioleiomyomatosis produces air trapping with large lung volumes. Pulmonary arterial hypertension usually indicates end-stage disease with pronounced obliteration of the pulmonary vasculature. Except for pulmonary vascular diseases, signs of pulmonary arterial hypertension are rarely identified.

HIGH-RESOLUTION COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY FEATURES OF INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE

Reticular or Linear Opacities

Reticular opacities usually are caused by interstitial thickening by cells, fluid, or fibrous tissue (Box 7-8).

Box 7-8 High-Resolution Computed Tomography Findings for Linear Opacities

Thickening of bronchovascular bundles (axial)

Interlobular septal thickening (septal lines)

Intralobular interstitial thickening

Axial Interstitial Thickening

Thickening of the axial interstitium (i.e., interstitium in a peribronchovascular location) (Fig. 7-6) occurs in many diseases, such as lymphangitic spread of carcinoma, pulmonary fibrosis, and sarcoidosis. It is manifested by bronchial wall thickening and apparent enlargement of central pulmonary vessels. The thickening may be smooth or nodular. This appearance must be differentiated from a primary airway problem, bronchiectasis. In bronchiectasis, the bronchi show evidence of bronchial wall thickening, but they also are dilated and larger than adjacent pulmonary artery branches. This results in the appearance of large ring shadows. In patients with isolated bronchiectasis, there are no other signs of lung disease.

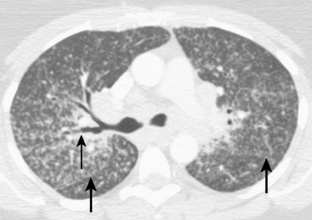

Interlobular Septal Thickening

Thickening of the interlobular septa (Fig. 7-7) is common in many interstitial lung diseases. In the peripheral lung, it appears as 1- to 2-cm lines that extend perpendicularly from the pleural surface into the substance of the lung. In the more central portion of the lung, the thickened septa can outline the secondary pulmonary lobules, producing polygonal structures that are 1 to 2.5 cm in diameter. These structures typically have a central dot that represents the pulmonary artery. Occasionally, lines that are 2.5 cm long and that outline more than one lobule can be identified, particularly in the periphery of the lung. They have been called parenchymal bands and long lines.

Centrilobular Abnormalities

Prominence of the central dot (Fig. 7-8) within the secondary pulmonary lobule (i.e., centrilobular vessel) may occur in a number of interstitial lung diseases. The intralobular bronchiole often becomes visible when there is centrilobular thickening. Centrilobular abnormalities can also be seen in patients with diseases of the peripheral airways (i.e., bronchioles).

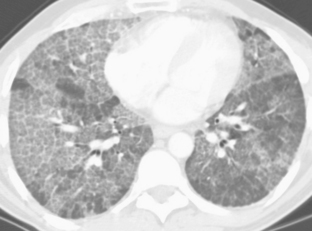

Intralobular Interstitial Thickening

Involvement of the interstitium within the lobule around the central artery and bronchiole or related to the interlobular septum may produce a fine reticular pattern within the lobule itself (Fig. 7-9). This usually extends from the centrilobular vessel peripherally to join a thickened septum.

Subpleural Lines

A subpleural line may be defined as a curvilinear opacity that is less than 1 cm from the pleural surface. It parallels the pleura and is a few millimeters thick (see Chapter 8). First described in asbestosis, a subpleural line occasionally is seen in normal lungs and results from dependent atelectasis.

Nodules and Nodular Opacities

Interstitial Nodules

Interstitial nodules (Fig. 7-10) tend to be well defined and can be seen in numerous interstitial lung diseases. They may be located in the axial interstitium along the peribronchovascular bundles, in the interlobular septa in a subpleural location adjacent to fissures, and in the central portion of the secondary pulmonary lobule.

Airspace Nodules

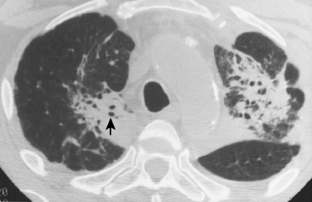

Ill-defined nodules that are 6 mm to 1 cm in diameter may be associated with airspace consolidation around the peripheral bronchioles, particularly around the terminal bronchiole in the center of the secondary pulmonary lobule. They are not truly acinar but may be considered airspace nodules (Fig. 7-11). They may be associated with more confluent areas of airspace consolidation with air bronchograms. These nodules may be seen in patients with lobular pneumonia, endobronchial spread of tuberculosis, or bronchioloalveolar carcinoma.

Masses of Fibrosis or Conglomerate Masses

Large masses of fibrous tissue may occur, usually in the central or axial interstitium (Fig. 7-12). They are usually associated with architectural distortion and volume loss. They typically produce traction bronchiectasis centrally in the bronchi that they encompass. This appearance is typical for silicosis and for coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, but it may also occur in end-stage sarcoidosis.

Cystic Pattern

Cystic abnormalities include honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis, lung cysts, and cavitary nodules. Findings related to emphysema and small airways disease (e.g., bronchiolitis, which may cause decreased lung opacity) are discussed in Chapters 10 and 13.

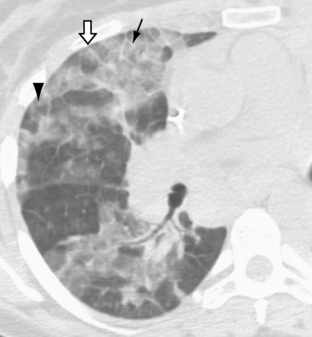

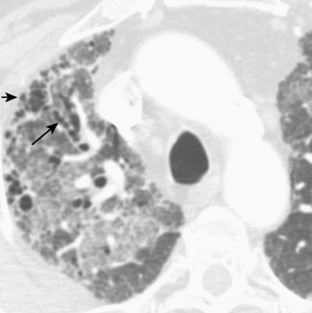

Honeycombing

Honeycombing is produced pathologically by the dissolution of alveolar walls with the formation of randomly distributed airspaces that are lined by fibrous tissue. Honeycombing represents an end-stage lung that is destroyed by fibrosis. The typical appearance of honeycombing is that of thick-walled cystic spaces that are usually less than 1 cm in diameter (Fig. 7-13). Honeycombing typically is in the peripheral portions of the lungs subpleurally, particularly in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. It is often accompanied by other signs of interstitial lung disease, especially the patterns associated with reticular opacities and architectural distortion.

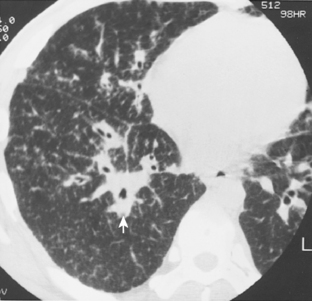

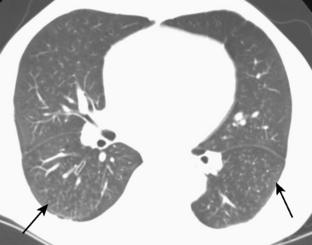

Traction Bronchiectasis

Traction bronchiectasis (Fig. 7-14) is a phenomenon that occurs in the presence of severe lung fibrosis and distortion of lung architecture, in which the fibrous tissue produces traction on the bronchial walls, resulting in irregular bronchial dilation. It usually involves the more central bronchi.