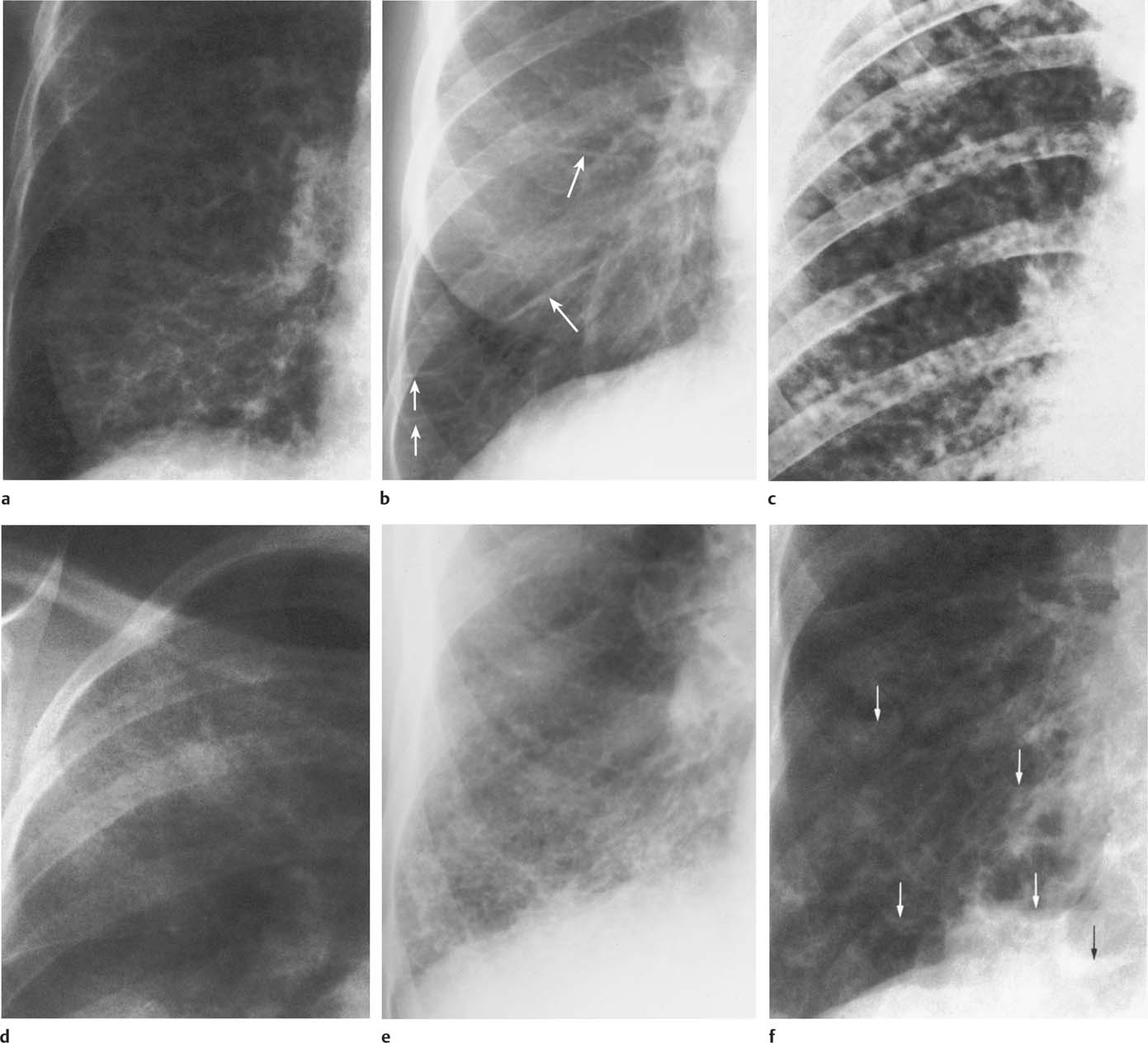

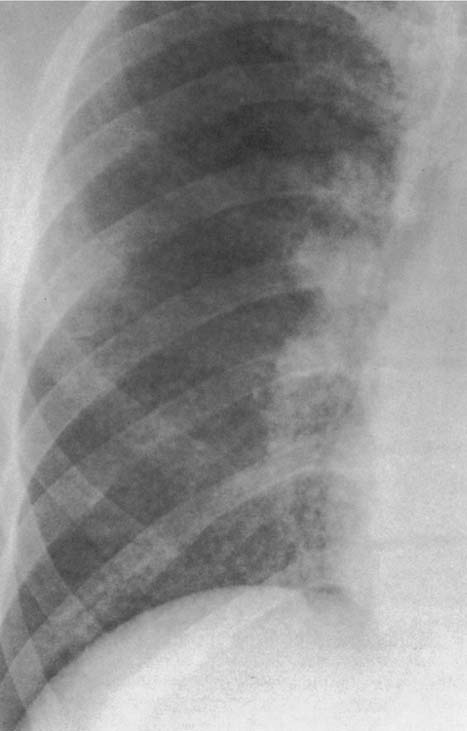

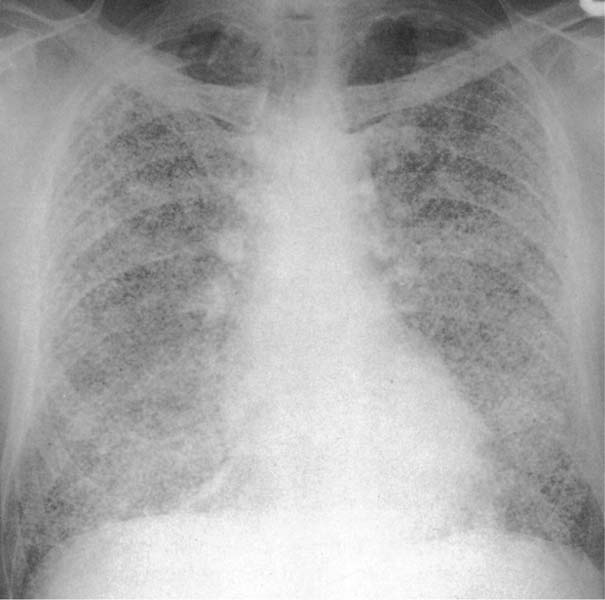

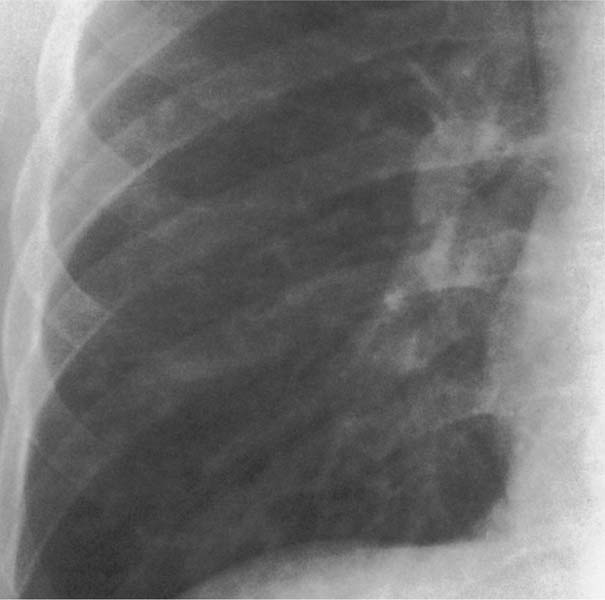

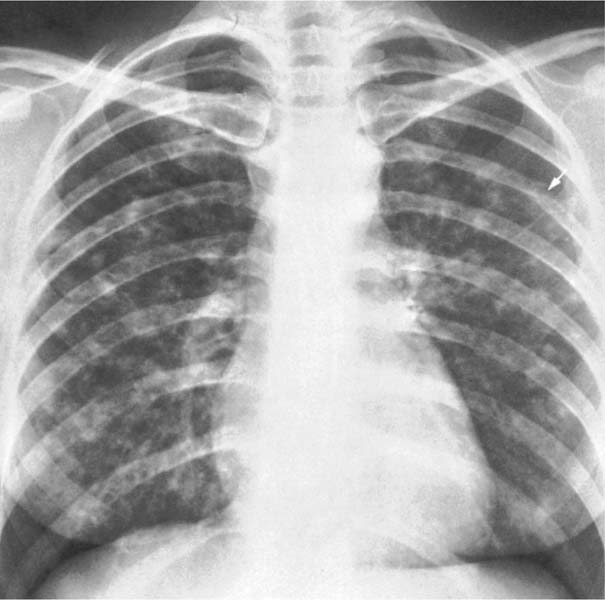

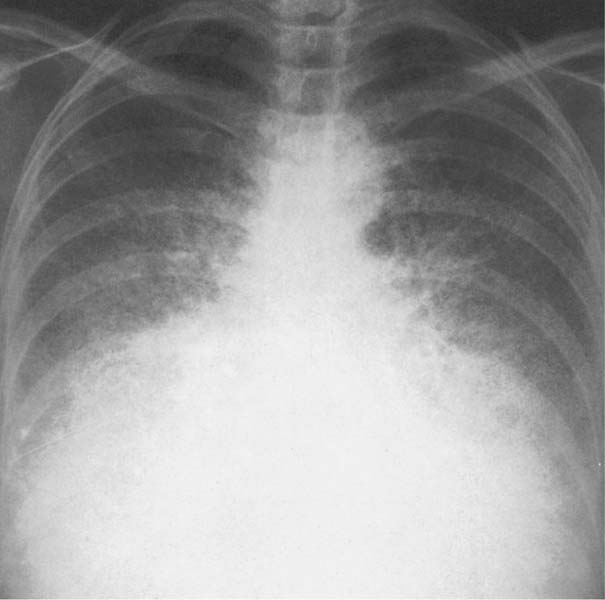

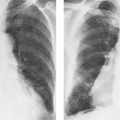

6 Interstitial Lung Disease Interstitial lung disease is diagnosed radiographically when a reticular, nodular, or honeycomb pattern or any combination thereof is recognizable. The reticular pattern consists of a network of linear densities (Fig. 6.1a). Depending on the mesh size, one can distinguish between fine, medium, and coarse reticular patterns, although this distinction has no obvious differential diagnostic significance. Kerley lines refer to septal lines that are thickened either by fluid accumulation, cellular infiltration, or connective tissue proliferation within the interlobular septa. Acute or transient Kerley lines are usually found with hydrostatic pulmonary edema (elevated microvascular pressure caused by left ventricular failure, renal disease and fluid overload), and occasionally with pneumonia and pulmonary hemorrhage. Acute Kerley lines are frequently associated with prominent interlobar fissures caused by subpleural edema. Permanent Kerley lines are most often present in chronic and severe pulmonary venous hypertension (especially mitral stenosis) that eventually results in fibrosis and hemosiderin deposition within the interlobular septa. Lymphatic obstruction appears to be a major factor in the development of Kerley lines associated with malignancies (e.g., lymphangitic carcinomatosis, bronchogenic carcinoma, and lymphoma), since at least histologically, ipsilateral hilar involvement with tumor is almost invariably present under such conditions. Finally, fibrosis of the interlobular septa can be associated with any form of pulmonary fibrosis, but is most frequently observed with pneumoconiosis. Different kinds of Kerley lines are distinguished: Kerley A lines are straight lines measuring 2–6 cm in length and approximately 1 mm in thickness. They are located in radiating fashion midway between the hilum and pleura and appear to cross over bronchoarterial bundles showing no anatomic relationship with the latter. Kerley A lines are usually best seen in the mid and lower lung fields. Kerley B lines are thinner and shorter than Kerley A lines (up to 2 cm) and lie in the lung periphery perpendicular to the lateral pleural surface (Fig. 6.1b). They are most numerous at the base of the lungs. Plate-like (discoid) atelectases and localized fibrotic strands can be differentiated from Kerley lines by their lack of a characteristic anatomic location and by the great variation in length and width of these densities. A nodular pattern (Fig. 6.1c) consists of numerous punc-tate densities essentially ranging in diameter from 1 mm (barely visible as an individual lesion) to 5 mm, although a few slightly larger nodular lesions can be interspersed. A purely nodular pattern is found with the hematogenous spread of certain infections and tumors, but can also be encountered with other diseases (Table 6.1). More often, however, nodular and reticular patterns are combined in the same patient, resulting in a reticulonodular appearance of the interstitial disease. A ground-glass appearance (Fig. 6.1d) is caused by a hazy increase in lung density that is not associated with obscuration of underlying vascular markings. It is found, besides in interstitial diseases, also with air-space disease (e.g. pneumocystis carinii pneumonia) and increased capillary blood volume (e.g. congestive heart failure). In interstitial disease it is produced when the fine reticulogranular pattern has progressed to such an extent that the overall density of the involved lung is increased, but the individual interstitial lesion is no longer recognizable. A honeycomb pattern is characterized by round or oval cystic lesions with a diameter up to 1 cm (Fig. 6.1e). In a given patient, they are relatively uniform in size and usually bunched together in grape-like clusters. Honeycombing is the only dependable radiographic sign of interstitial fibrosis. It may present radiographically in a reticulonodular pattern, too, but this presentation is also found with many other disorders, including various acute abnormalities that can resolve completely with time. Cystic bronchiectases may produce a radiographic picture similar to honeycombing. However, they can usually be differentiated from honeycombing by their larger and less uniform size and by the presence of tiny meniscus-like fluid levels at the bottom of these cystic lesions. Diseases that cause a characteristic honeycomb pattern are summarized in Table 6.2. The majority of interstitial lung diseases involve both lungs, or stated differently, the interstitial disease is usually diffuse, although some areas may be more affected and others more or less spared. Truly localized interstitial lung disease is relatively rare and most often of an infectious etiology. Mycoplasma and viral pneumonias can present in their early stages as localized interstitial diseases of fine reticular appearance before the extension of the inflammation into the air spaces causes a consolidation. Localized fibrotic changes are often found in the chronic stage of a disease (e. g., tuberculosis and radiation pneumonitis). Finally, fibrotic scars may be the sequelae of virtually any disease capable of damaging the lung parenchyma severely enough. Both congenital and acquired bronchiectases can be mistaken radiographically for localized interstitial lung disease (Fig. 6.1f). In approximately 50% of cases, they are limited to one lung. Cylindrical bronchiectases present as tubular opacities with parallel walls of 1 mm or slightly larger thickness. When these bronchiectatic segments become filled with retained secretion, they appear as homogeneous band-like densities (“gloved-finger” shadows). Varicose and cystic (saccular) bronchiectases are often evident on plain radiography as cystic lesions up to 2 cm in diameter and often containing a small air-fluid level at the bottom. This appearance is virtually diagnostic, although under very rare circumstances both pulmonary papillomatosis and paragonimiasis may mimic cystic bronchiectases. Bronchiectases are often associated with loss of volume and crowding of the lung markings in the affected area together with compensatory overinflation of the spared lung (Fig. 6.2). Table 6.3 summarizes all disorders that demonstrate radiographically a diffuse reticular or reticulonodular pattern characteristic of interstitial lung disease. Fig. 6.1a–f Patterns of interstitial lung disease. a Reticular pattern (Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia). b Kerley A lines (long arrows, touched up) and Kerley B lines (short arrows) (mitral stenosis). c Nodular pattern (silicosis). d Ground-glass appearance produced by the summation of innumerable tiny retlculogranular densities (sarcoidosis). e Honeycomb pattern (idiopathic interstitial fibrosis). f Bronchiectases evident as cystic lesions varying considerably in size and characteristically containing small air-fluid levels (arrows). Fig. 6.2 Bronchiectases. Extensive, predominantly cystic bronchiectases in the right lung and left lower lobe are associated with loss of volume in the affected lung and compensatory overinflation of the nonaffected left upper lobe.

Disease | Characteristics of Nodules |

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (alveolar cell carcinoma) (Fig 6.3) | Often poorly defined, confluent nodules of varying size. Roentgenographic pattern of disseminated alveolar cell carcinoma may be fairly uniform throughout both lungs or vary regionally. |

Metastases (e.g., carcinomas from thyroid, lung, breast or gastrointestinal tract, or melanomas, sarcomas and lymphomas) (Fig. 6.4) | Usually well defined and of varying size. |

Pneumonias |

|

Staphylococcus aureus | Miliary and larger, often poorly defined; can form microabscesses. |

Salmonella | Miliary. |

Pseodomonas pseudomallei | 4 to 10 mm, poorly defined (early acute stage of disease). |

Listeriosis (newborn) | Intrauterine infection with high mortality rate. |

Tuberculosis (Fig. 6.5) | Miliary, discrete (DD: tuberculomas that are larger than 5 mm and can calcify). |

Histoplasmosis (Fig 21.6) | 2 to 4 mm, discrete. Can result in nodular calcifications 1 to several years later. |

Coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, and Cryptococcosis (Fig. 6.7) | Miliary and larger (up to 3 cm). Calcification extremely rare. |

Candidiasis | Miliary (rare manifestation) |

Varicella (chickenpox) pneumonia (Fig. 6.8) | Miliary and larger, poorly defined. Healing may result in punctate calcifications years later, |

Schistosomiasis | Miliary |

Filariasis | Miliary and slightly larger (up to 5 mm). Predominantly in the mid- and lower-lung fields. |

Sarcoidosis (Fig. 6.9) | Miliary and larger, often indistinctly defined. |

Pneumoconiosis (inorganic dust) (e.g., silicosis, coal miner’s lung, berylliosis) (Figs. 6.10 and 6.11) | Miliary and larger. Fairly well defined in silicosis and poorly in berylliosis. Calcification occurs. |

Pneumoconiosis caused by radiopaque dusts (iron, tin, barium, antimony and rare-earth compounds) (Figs. 6.12 and 6.13) | Finely granular stippling uniformly distributed over both lung fields. Density of the tiny nodules depends on the atomic number of the inhaled element. |

Silo filler’s disease (NO2 inhalation) | Miliary nodulation only manifest 2–5 weeks after initial exposure (third phase of disease). |

Extrinsic allergic alveolitis (e.g., farmer’s lung, bird-fancier’s lung, mushroom-worker’s lung, bagassosis, and others) (Figs. 6.14 and 6.15) | Miliary and larger, usually poorly defined (acute stage). Often less evident in apices and bases. |

Rheumatoid lung | Miliary and larger (in early stage). |

Wegener’s granulomatosis | Multiple nodules ranging from a few millimeters up to 10 cm. |

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (eosinophilicgranuloma) (Fig. 6.16) | Miliary and larger with mid and upper lung fields predominance. This presentation is seen in the active stage, which may completely resolve or progress to the chronic fibrotic stage. |

Gaucher’s disease | Miliary and larger. |

Niemann-Pick syndrome | Miliary and larger. |

Interstitial edema (cardiogenic) | Symmetrical, miliary nodulation, preferentially located in the lower-lung fields. May occasionally be the dominant feature. |

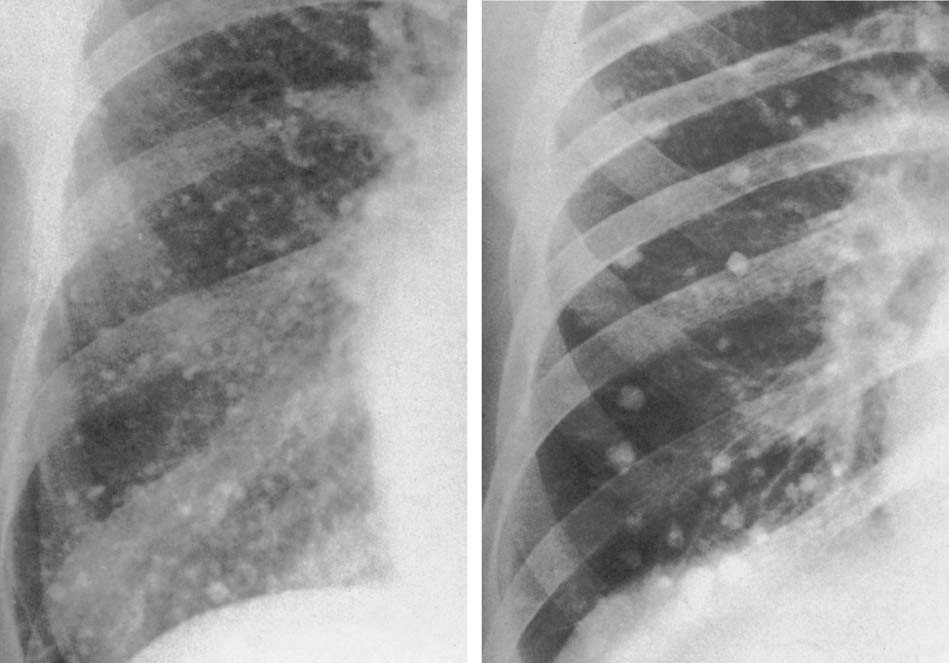

Hemosiderosis and pulmonary ossification secondary to mitral stenosis (Fig. 6.17) | Punctate densities (hemosiderosis) and densely calcified 2 to 8 mm nodules (pulmonary ossification), predominantly in the mid and lower lung fields, usually more numerous on the right side. Hemosiderosis-like pulmonary calcifications are occasionally seen in chronic renal failure (see Fig. 7.29). |

Bronchiolitis acute or obliterans | Miliary and larger |

Amyloidosis (diffuse alveolar septal form) | Miliary and larger |

Talc granulomatosis secondary to intravenous drug abuse | Discrete, 1 mm and smaller, may slowly increase in size and number over months and years. |

Alveolar microlithiasis (Fig. 6.18) | Discrete and extremely sharply defined, less than 1 mm in diameter. |

Oily contrast material embolism (e.g., secondary to lymphography) (Fig. 6.19) | Finely granular and relatively dense stippling preferentially located in the posterior (dependent) parts of the lungs and most obvious a few hours after lymphography. |

Fig. 6.3 Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Poorly defined, confluent nodules are seen bilaterally, but only shown for the right side.

Fig. 6.4 Metastases from breast carcinoma. Numerous nodules measuring only a few millimeters in diameter are present bilaterally, but are only shown for the right lower lung field.

Fig. 6.5 Miliary tuberculosis. Numerous discrete nodules measuring 1 to 3 mm in diameter are seen bilaterally, but are only shown for the right side.

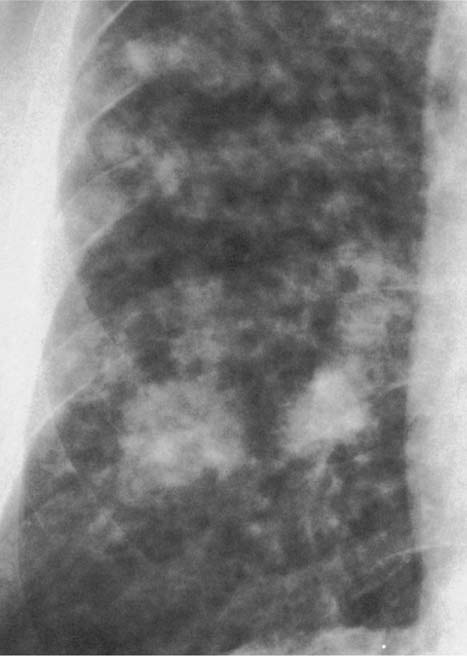

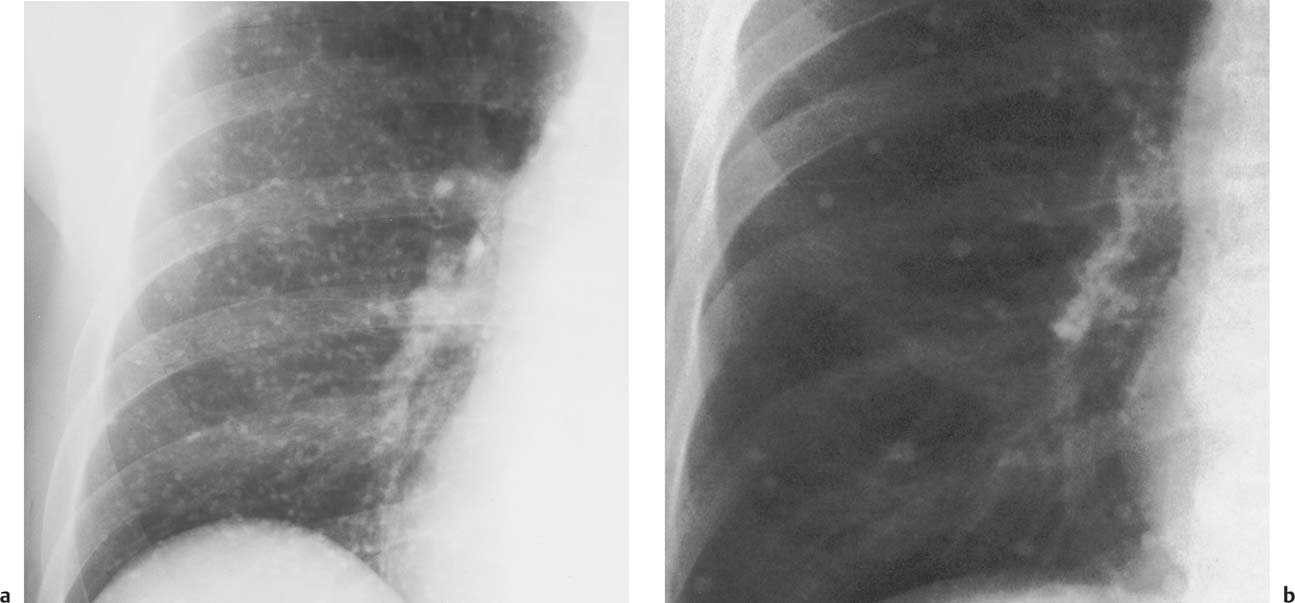

Fig. 6.6 Histoplasmosis (2 cases). Bilateral miliary (a) and larger (b) scattered calcified nodules are present, but only shown for the right side.

Fig. 6.7 Aspergillosis. Diffuse bilateral poorly defined small nodular densities are present, but only shown for the right lower lung field.

Fig. 6.8 Varicella (chickenpox) pneumonia. Poorly defined nodular densities are seen bilaterally, but are only shown for the right lower lung field.

Fig. 6.9 Sarcoidosis. Multiple small nodules of variable sizes are seen bilaterally, but are only shown for the right mid lung field.

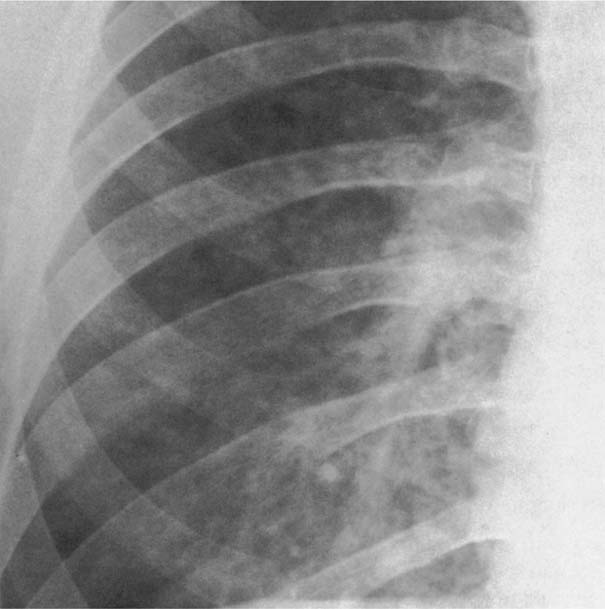

Fig. 6.10 Silicosis. Numerous fairly well defined miliary nodules are seen bilaterally besides diffuse reticular changes and early honeycombing, but are only shown for the right side.

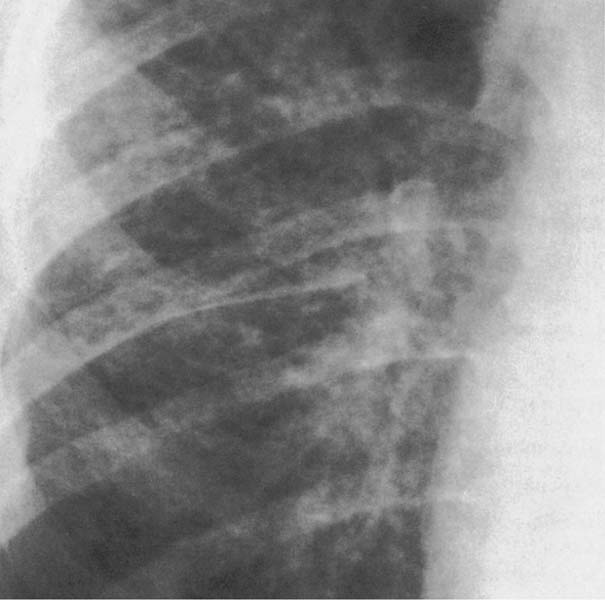

Fig. 6.11 Berylliosis. Numerous relatively poorly defined miliary nodules and bilateral hilar enlargement are present, but are only shown for the right side. Findings simulate sarcoidosis radiographically.

Fig. 6.12 Siderosis. Bilateral small nodules with preferential involvement of the mid and lower lung zones are seen in this arc welder that are not associated with hilar adenopathy or fibrosis and resolved after exposure was discontinued. Only the right lower lung field is shown.

Fig. 6.13 Stannosis (inhalation of tin oxide). Multiple tiny nodules of high density are distributed evenly throughout both lungs, sparing only the apices.

Fig. 6.14 Farmer’s lung. Bilateral poorly defined nodules are present.

Fig. 6.15 Bird-fancier’s lung. Multiple small nodules are scattered throughout both lung fields.

Fig. 6.16 Langerhans cell histiocytosis (eosinophilic granuloma). Multiple poorly defined nodules are seen bilaterally. Note also the lytic involvement of the left fifth rib with pathologic fracture (arrow).

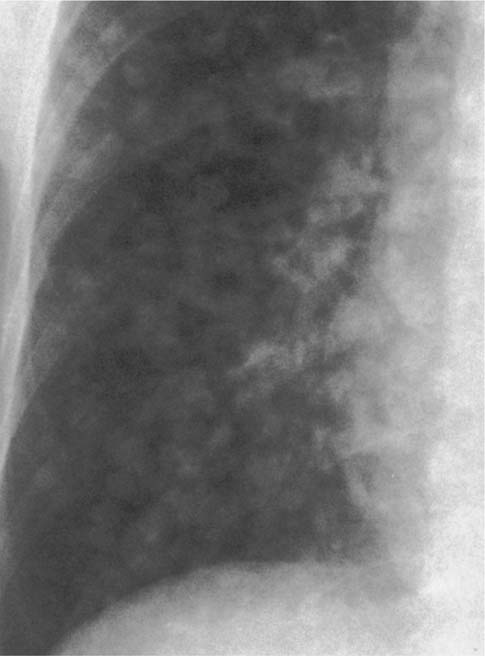

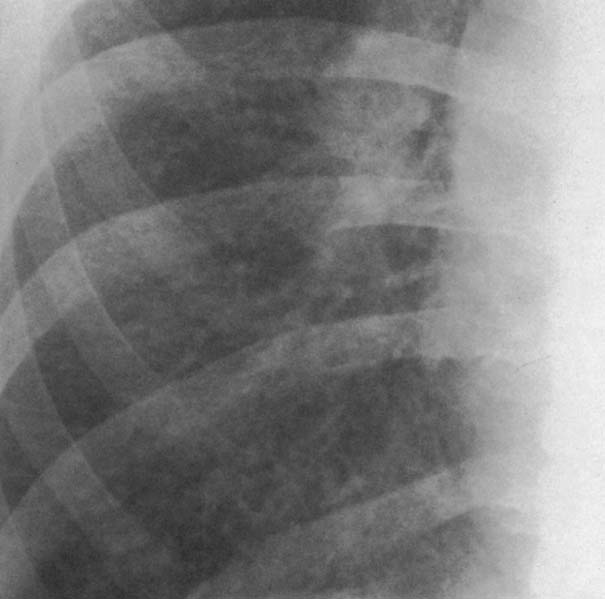

Fig. 6.17 Mitral stenosis (2 cases). a Punctate densities (hemosiderosis), and b larger calcified nodules (pulmonary ossification) are seen bilaterally, but only shown for the right side.

Fig. 6.18 Alveolar microlithiasis. Innumerable, extremely sharply defined, tiny densities measuring less than 1 mm in diameter are seen bilaterally.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree