, Joungho Han2, Man Pyo Chung3 and Yeon Joo Jeong4

(1)

Department of Radiology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(2)

Department of Pathology Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(3)

Department of Medicine Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

(4)

Department of Radiology, Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea, Republic of (South Korea)

Abstract

Collagen vascular diseases (CVDs) showing features of interstitial lung disease (ILD) pattern include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS), dermatomyositis (DM) and polymyositis (PM), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), Sjögren’s syndrome, and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD). Histopathologically, interstitial lung diseases associated with CVD are diverse and include nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), apical fibrosis, diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) patterns (Tables 28.1 and 28.2). NSIP accounts for large proportion, especially in PSS, DM and PM, and MCTD. More favorable prognosis in interstitial pneumonia associated with CVDs than in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) may be explained by the larger proportion of NSIP pattern than UIP pattern. Thin-section CT (TSCT) seems to help characterize and determine the extent of ILD in CVDs [1].

Collagen vascular diseases (CVDs) showing features of interstitial lung disease (ILD) pattern include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS), dermatomyositis (DM) and polymyositis (PM), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), Sjögren’s syndrome, and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD). Histopathologically, interstitial lung diseases associated with CVD are diverse and include nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), apical fibrosis, diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) patterns (Tables 28.1 and 28.2). NSIP accounts for large proportion, especially in PSS, DM and PM, and MCTD. More favorable prognosis in interstitial pneumonia associated with CVDs than in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) may be explained by the larger proportion of NSIP pattern than UIP pattern. Thin-section CT (TSCT) seems to help characterize and determine the extent of ILD in CVDs [1].

Table 28.1

Frequency of involvement of interstitial pneumonia and other pulmonary diseases in various collagen vascular diseases

SLE | RA | PSS | DM/PM | Sjögren’s syndrome | MCTD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

UIP | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

NSIP | + | + | ++++ | ++++ | + | +++ |

DAD | ++ | + | + | + | ||

BOOP | + | + | ++ | + | ||

LIP | +++ | + | ||||

Hemorrhage | +++ | |||||

Airway disease | ++ | ++ |

Table 28.2

Most common pathologic and radiologic findings of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias

Histologic pattern | Pathology | Radiologic findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Common radiographic findings | Distribution on CT | Usual CT findings | ||

UIP | Architectural destruction, fibrosis with HC, fibroblastic foci; alternating areas of normal lung, inflammation, fibrosis, and honeycombing (temporally heterogeneous) | Reticular abnormality with volume loss, basal | Peripheral, subpleural, basal | Irregular linear opacity, HC, traction bronchiectasis/bronchiolectasis, architectural distortion, focal ground-glass opacities |

NSIP | Varying proportion of interstitial inflammation and fibrosis, divided into cellular (inflammation) and fibrosing (fibrosis) patterns; patchy with intervening normal lung; temporally uniform | GGO and reticular opacity, basal | Peripheral, subpleural, basal, symmetric | GGO, irregular linear opacities, consolidation |

COP | Intraluminal organizing fibrosis in distal airspaces; patchy; preservation of lung architecture; temporally uniform; mild chronic interstitial inflammation | Patchy bilateral consolidation | Subpleural and/or peribronchovascular | Patchy consolidation and/or nodules |

DAD | Alveolar edema, hyaline membrane, fibroblastic proliferation with little mature collagen; diffuse; temporally uniform | Progressive diffuse GGO or consolidation | Diffuse | Consolidation, GGO, often with lobular sparing; traction bronchiectasis later |

LIP | Infiltration of T lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages; lymphoid hyperplasia; diffuse; predominantly septal | Reticular opacities, nodule | Diffuse | Centrilobular nodules, GGO, septal and bronchovascular thickening, thin-walled cysts |

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

Pleuropulmonary involvement occurs in approximately 50–60 % of SLE patients [1]. Most involvements are pleural diseases. In one prospective study including 1,000 patients, lung involvement was identified only in 3 % at the onset of the disease; an additional 7 % developed lung disease over the period of observation [2]. Pulmonary manifestations of SLE comprise both acute and chronic lesions. Acute disease includes pulmonary hemorrhage, acute lupus pneumonitis (Fig. 28.1), and pulmonary edema. Chronic disease such as interstitial pneumonitis and fibrosis is less common in SLE than in other connective tissue disorders [3].

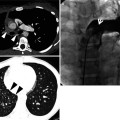

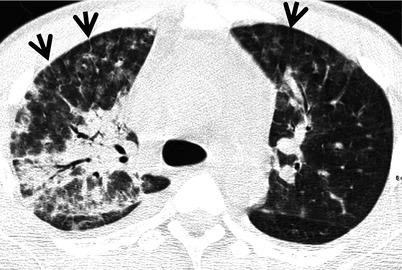

Fig. 28.1

Acute lupus pneumonitis in a 47-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lung window image of CT scan (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at level of azygos arch shows patchy and extensive areas of parenchymal opacity in upper lung zones. Also note mild and smooth thickening of interlobular septa (arrows)

Acute lupus pneumonitis occurs in 1–4 % of patients. Histopathologic findings of acute lupus pneumonitis include alveolar wall damage and necrosis leading to inflammatory cell infiltration, hemorrhage, edema, and hyaline membrane formation. Thrombi in small vessels, associated with an interstitial pneumonitis, have been well documented, although this is an unusual feature of acute lupus pneumonitis [3].

Diffuse interstitial pneumonitis and fibrosis is uncommon; in one series of 120 patients, only 5 (4 %) showed the interstitial lung disease [4]. Pathologic findings in these cases are those of UIP or NSIP pattern (Fig. 28.2). A few cases of COP pattern have been reported [1].

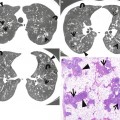

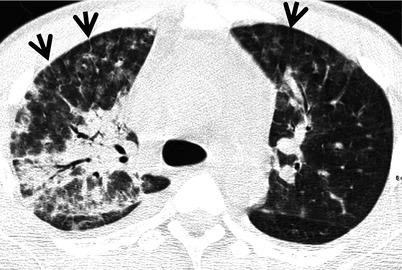

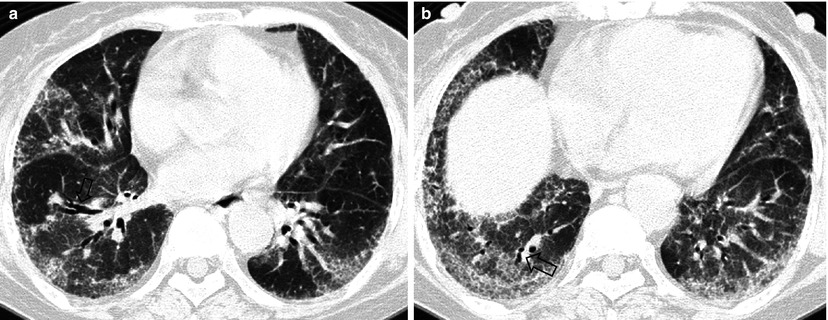

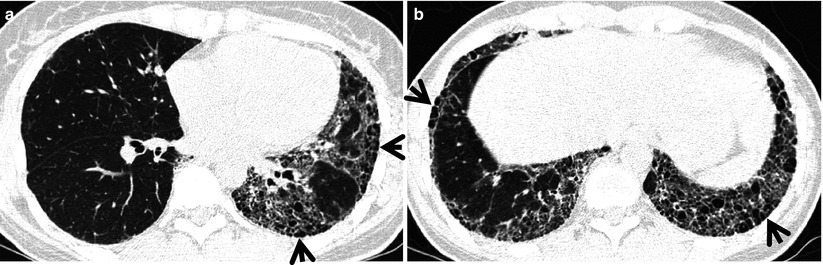

Fig. 28.2

Pulmonary fibrosis of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern in a 37-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. (a, b) Lung window of CT scans (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of inferior pulmonary veins (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show patchy areas of ground-glass opacity and reticulation in subpleural lungs and along bronchovascular bundles in both lungs. Also note traction bronchiectasis (open arrows)

Radiographic evidence of interstitial fibrosis, consisting of a reticular pattern involving mainly the lower lung zones, is seen in only about 3 % of patients who have SLE. By contrast, interstitial abnormalities are seen in approximately 30 % of patients on TSCT [5, 6]. These include interlobular septal thickening (33 %), irregular linear opacity (33 %), and architectural distortion (22 %). Such abnormalities are usually mild and focal; diffuse disease occurs in only 4 % of patients [4]. Honeycombing (HC) is uncommon. Ground-glass opacity (GGO) and consolidation on TSCT may reflect the presence of interstitial pneumonitis and fibrosis, acute lupus pneumonitis, hemorrhage or, occasionally, COP pattern of lung abnormality.

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

Pleuropulmonary complications in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are common and include interstitial pneumonitis and fibrosis, rheumatoid (necrobiotic) nodules, COP pattern of lung abnormality (Fig. 28.3), bronchiectasis, bronchiolitis obliterans, follicular bronchiolitis, and pleural effusion or thickening [1]. Interstitial pneumonitis and fibrosis are the most common pulmonary manifestation of RA (Fig. 28.4). Evidence of interstitial fibrosis is seen on chest radiographs in approximately 5 % of patients with RA [7] and on TSCT in 30–40 % [8]. The complication is seen most frequently in men between 50 and 60 years of age [9].

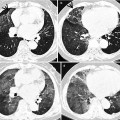

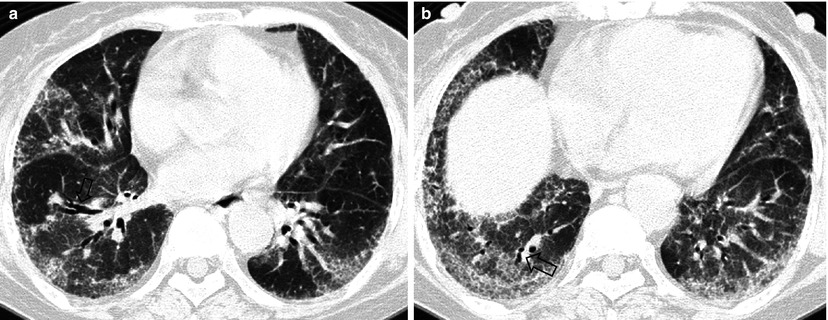

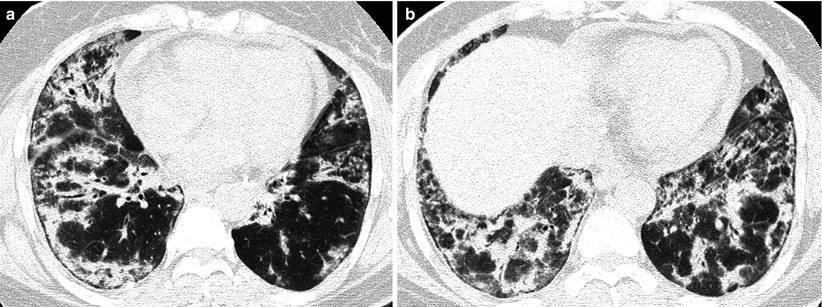

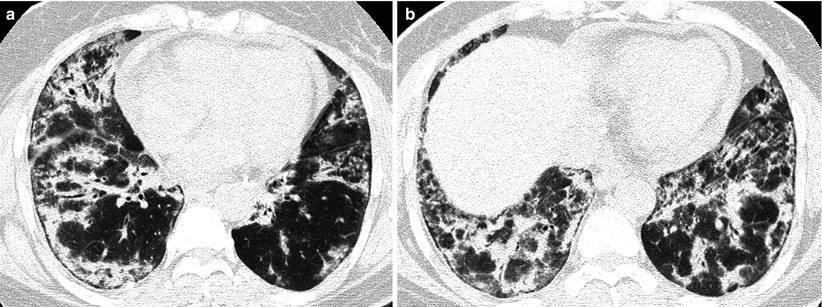

Fig. 28.3

Interstitial pneumonia of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia pattern in a 48-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis. (a, b) Lung window of CT scans (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of inferior pulmonary veins (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show patchy areas of consolidation in both lungs, distributed along bronchovascular bundles or along subpleural lungs

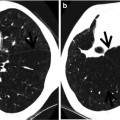

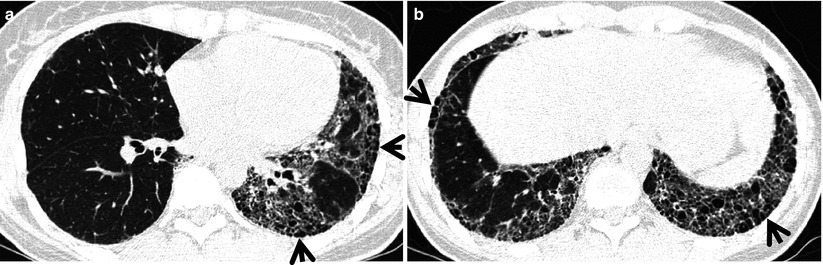

Fig. 28.4

Interstitial fibrosis of usual interstitial pneumonia pattern in a 35-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis. (a, b) Lung window of CT scans (2.5-mm section thickness) obtained at levels of inferior pulmonary veins (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show patchy areas of reticulation in both lungs. Also note honeycomb cysts (arrows)

The majority of patients who have interstitial fibrosis associated with RA have UIP pattern of lung abnormality (Fig. 28.4); a small percentage has histologic findings of NSIP pattern [1]. Nodular aggregates of lymphocytes may be prominent in both the parenchymal interstitium and in the interstitial tissue in bronchiolar walls and interlobular septa (follicular bronchiolitis). According to a report, a wide variety of histopathologic features were seen in open lung biopsy from patients with rheumatoid lung disease [10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree