Interventional Thyroid Ultrasound

Ultrasonography is superior to all other imaging modalities (scintigraphy, CT, MRI, PET) for imaging the thyroid gland. Ultrasound is an essential tool in the work-up of thyroid diseases and dysfunction and is the next diagnostic step following the history, physical examination, and key laboratory tests (thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH], free thyroxine [fT4], free triiodothyronine [fT3]).1

Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures in the thyroid gland have both diagnostic and therapeutic applications:

Biopsies:

Fine needle aspiration (FNA)

Core needle biopsy (CNB)

Fluid evacuation:

Single or repetitive needle aspirations

Catheter drainage

Ablative procedures:

Percutaneous ethanol instillation (PEI)

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA, performed rarely)

Percutaneous laser ablation (PLA, performed rarely)

27.1 Diagnostic Interventions

In the traditional technique of thyroid biopsy, a palpable or visible tumor, nodule, or cyst in the thyroid gland is fixed between the thumb and index finger of one hand while the needle is introduced into the mass with the other hand. Diagnostic accuracy can be increased by making 2 to 6 passes, in each case using a new needle and syringe, and preparing additional smears for evaluation.2

Ultrasound guidance has improved this technique. Nonpalpable nodules and lesions can be biopsied, and sonographically suspicious nodules and peripheral vascularized areas in cystic lesions can be accurately targeted while avoiding injury to the trachea, common carotid artery, and jugular vein. Ultrasound visualization of the needle tip allows for continuous and precise monitoring of the needle path. In contrast to palpation-guided biopsies, one needle insertion is generally sufficient. A second pass may be necessary only if the initial aspirate is bloody or when dealing with a large, inhomogeneous mass. Ultrasound guidance has decreased the rate of nondiagnostic biopsies, improved diagnostic accuracy, and reduced costs. Ultrasound-guided FNA biopsy has reduced by 25% the number of suspicious goiters selected for surgery and has increased the rate of carcinomas found in surgical specimens from <15% to 40 to 50%.3–6 The guidance of thyroid biopsy by palpation has become obsolete.

27.1.1 Indications

The most frequent indication for thyroid biopsy is the investigation of suspicious thyroid nodules. The sonographic criteria of malignancy are as follows:

Low echogenicity

Inhomogeneous echo pattern

Presence of microcalcifications

Ill-defined or microlobulated margins

Irregular intranodal vascularity

Hard nodule by elastography

A single criterion is not suspicious for malignancy in itself, but two or more criteria warrant a high index of suspicion. The size of the nodule is not a factor.7,8 Larger malignancies tend to show central cystic transformation, so partially cystic nodules should be biopsied at their periphery. Other factors that influence patient selection for thyroid biopsy are the history (first-degree relative with thyroid cancer, prior radiation exposure), clinical criteria (hoarseness, hard palpable nodule), laboratory findings (calcitonin), and other sonographic criteria (transmural extension, lymphadenopathy).9

The most common indications for percutaneous thyroid biopsy are:

Thyroid nodule with clinical, sonographic or scintigraphic criteria suspicious for malignancy (▶ Fig. 27.1a, b)

Confirmation of diagnosis of subacute granulomatous thyroiditis (▶ Fig. 27.2a, b)

Confirmation of diagnosis of chronic Hashimoto thyroiditis or investigation of suspected lymphoma (▶ Fig. 27.3)

Confirmation of diagnosis of acute thyroiditis, identification of infecting organism (▶ Fig. 27.4)

Symptomatic thyroid cysts before sclerotherapy

Lymph node enlargement after thyroid cancer surgery

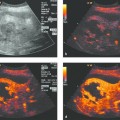

Fig. 27.1

a Medullary thyroid carcinoma displaying multiple sonographic criteria of malignancy: low echogenicity, inhomogeneity, microcalcifications, and ill-defined margins.

b Papillary thyroid carcinoma with marked hypoechogenicity and ill-defined margins. Arrows indicate the 20-gauge needle.

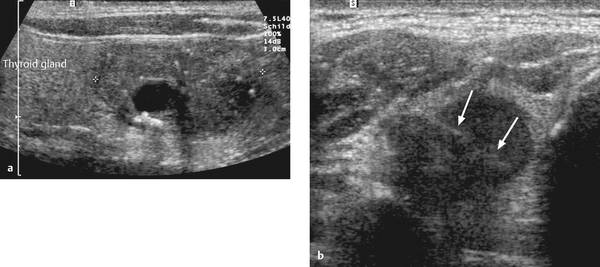

Fig. 27.2

a Transverse scan of the neck in a 45-year-old woman shows an inhomogeneous area in the right thyroid lobe (+ +), which was slightly tender to pressure. Laboratory tests showed elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). The patient had received neck radiation for a cervical hemangioma in childhood. Differential diagnosis: tumor infiltration, subacute thyroiditis. FNA: subacute granulomatous thyroiditis.

b Color Doppler ultrasound (power Doppler) shows hypoechoic inflammatory infiltrates with scant vascularity.

Fig. 27.3 Enlarged, hypoechoic thyroid gland in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and vitiligo. FNA biopsy was performed using classic technique. Ultrasound displays the oblique needle shaft (left side of image). Cytology and histology detected lymphocytic infiltration: rare form of Hashimoto thyroiditis with thyroid enlargement.

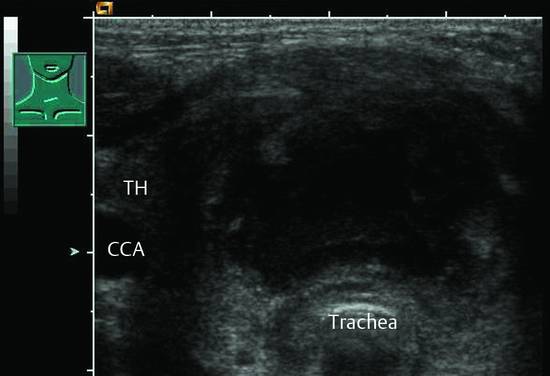

Fig. 27.4 Very tender thyroid gland (TH) in a small child with local warmth and swelling in the neck. FNA cytology and bacteriology indicated acute thyroiditis with abscess formation caused by staphylococcal infection.

27.1.2 Contraindications

The contraindications to thyroid FNA are as follows:

Significant coagulopathy (PTT > 50 seconds, INR > 1.6, platelets < 50 × 109/L)

Lack of therapeutic implications

Lack of informed consent

27.1.3 Methods

Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA)

Aspiration cytology is the method of choice for differentiating between benign and malignant thyroid nodules. The FNA of suspicious thyroid nodules has a sensitivity of 83% (65–98%) and a specificity of 92% (72–100%). The rate of false-negative findings in the literature ranges from 1.1 to 23.7%.9–11 The high range of variation is due mainly to differences in the expertise of operators and cytologists. Even small nodules (<5 mm) can be confidently sampled and classified.12

Core Needle Biopsy (CNB)

Generally there will be no difficulty in the cytologic classification of thyroid malignancies when an adequate specimen is obtained and the general cytologic criteria for malignancy are applied (nuclear pleomorphism, nuclear hyperchromasia, irregular nuclear membrane, prominent nucleoles, multinucleated tumor giant cells, marked cellular dissociation).

In the case of anaplastic carcinomas, it can be extremely difficult to make an accurate cytologic or even histologic diagnosis. Accurate classification is important due to differences in prognosis and treatment, as in the differentiation of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma from high-grade lymphoma. A core needle biopsy of the thyroid may be necessary in selected cases to provide a histologic diagnosis based in part on immunohistochemical tests.9 This is particularly true in patients with thyroid lymphoma13,14 and in rare cases of sarcoma or hemangioendothelioma.

Because of contradictory results on the diagnostic accuracy of CNB versus FNA, the latter is still considered the basic method of choice for the diagnostic evaluation of suspicious thyroid nodules.15–17

27.1.4 Complications

Owing to the superficial location of the thyroid gland, compression of the needle tract is sufficient to prevent bleeding even in patients with coagulation disorders. There is no need to discontinue aspirin use before thyroid biopsy.

Hematomas are the most common minor complication of FNA and occur in 0.2% of needle biopsies. Major complications occur only sporadically and have not been documented in large studies.11,18

Seeding of tumor cells along the needle tract is a rare occurrence and generally has no significance because even an inoculation metastasis can easily be removed.19

Core needle biopsy appears to be associated with a slightly higher rate of minor complications (hematoma, infection) than FNA. No major complications have been reported.15–17

27.1.5 Materials and Equipment

Ultrasound Technology

Ultrasound imaging of the thyroid gland requires the use of high-frequency transducers (7.5–12 MHz). A very large goiter with retrosternal extension should additionally be scanned with a curved array at 5 to 7.5 MHz to obtain a more comprehensive view of the mass and its surroundings. The ultrasound probe should have the smallest possible footprint to facilitate needle insertion and guidance in the neck (▶ Fig. 27.5).

Fig. 27.5 FNA using the long-axis technique. The 20-gauge needle, mounted on a 5-mL syringe, is introduced at a 45° angle to the skin at the narrow end of the ultrasound probe.

Color Doppler imaging (conventional or power Doppler) can clearly display movements of the biopsy needle, fluid aspiration from a cyst, or ethanol injection into a lesion (▶ Fig. 27.6a, b).

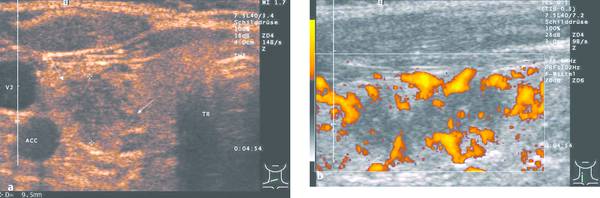

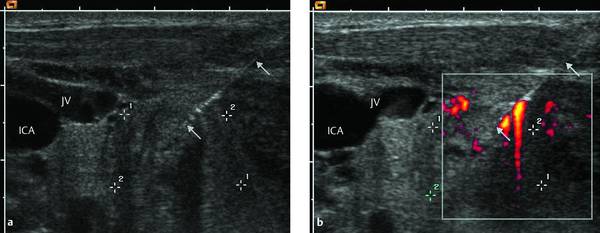

Fig. 27.6

a Transverse scan of the right thyroid lobe. Viewed in the B-mode image, the full length of the needle (arrows) is visible within the inhomogeneous, poorly marginated thyroid nodule (+ +) and in its course through the subcutaneous tissue and neck muscles. The lower arrow indicates the needle tip.

b Brisk movements of the needle produce color artifacts in the color Doppler image, similarly to the aspiration of cyst contents or the injection of alcohol. (ICA, internal carotid artery; JV, right jugular vein.)

For ethanol instillation into autonomous hyperfunctioning thyroid adenomas, we use the vascularity of the nodule on contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) for guiding a second or third injection. Ethanol is selectively instilled into nodular areas that exhibit vascularity.

Dedicated biopsy transducers have several disadvantages: they are expensive; the angle of needle insertion is difficult to vary; imaging is limited in the area of the transducer orifice; and the biopsy transducer has to be sterilized after each use. In our experience, even side-mounted needle guides are not a helpful aid in performing thyroid biopsies.

Biopsy Materials

Standard biopsy materials and supplies are illustrated in ▶ Fig. 27.7.

Fig. 27.7 Materials for FNA biopsy, core needle biopsy, and ethanol injection: skin prep solution (Kodan tincture forte [Schülke & Mayr]); 20-gauge needles in two lengths; 5- and 10-mL syringes; 18-gauge automated core biopsy needle (Biopince [Argon Medical Devices]); specimen vessel with 4% formalin; microscope slides; ampule with 10 mL of 96% ethanol; nonsterile gloves; adhesive dressing; and spray fixative (Merckofix [Merck Millipore]).

We use (economical) 20-gauge hypodermic needles for thyroid FNA, like those commonly used for drawing blood. They are 0.9 mm in diameter, 4 or 7 cm long, and can be clearly visualized with ultrasound. We use 2- or 5-mL syringes to draw samples for aspiration cytology as well as for therapeutic ethanol instillation. Either 20- or 50-mL syringes are used for the drainage of thyroid cysts, depending on the cyst contents.

Some histologic specimens are obtained with fine needles 0.8 to 0.9 mm in diameter (approximately 21- to 20-gauge). We perform core biopsies with 18-gauge end-cutting needles in an automated biopsy instrument with one-hand operation (Biopince, Argon Medical Devices). The biopsy process is simple and can retrieve long tissue cores whose diameters equal the full luminal diameter of the needle.

27.1.6 Preparation

The purpose of the procedure, possible alternatives, and the steps involved in the procedure are fully explained to the patient with a nurse or other assistant present, and written consent is obtained. The patient is also informed that two or perhaps three passes may have to be made, depending on the quality of the sample, and that thyroid biopsy is comparable to a peripheral venipuncture. Most biopsies are performed on an outpatient basis. Generally the total time required for an ultrasound-guided thyroid biopsy, including preparations, ultrasound examination and postprocedure care, is less than 15 minutes.

Positioning the Patient

The patient is positioned supine with the upper body elevated 45° to 50°. A roll is placed beneath the cervical spine to hyperextend the neck and increase the distance between the lower jaw and the clavicle or sternum. This position also makes it easier to visualize retrosternal portions of the thyroid20 and allows the sonographer to work in a conventional position.

Recommendations on Selecting the Target Site

While a cyst can be aspirated at any site, selection of the target site is important in the case of solid and suspicious nodules. This has been demonstrated by comparisons of preoperative ultrasound findings with surgical specimens. When dealing with a nodule that is suspicious for malignancy, the periphery of the lesion should be biopsied because that is where tumor cells tend to proliferate. Central areas are more likely to be necrotic, resulting in a more difficult cytologic diagnosis.20,21 Predominantly cystic nodules should be biopsied in a solid area.22

Antisepsis

The skin is prepared with an alcohol-based solution after first shaving the site if necessary. The transducer is cleaned and thoroughly disinfected before use (e.g., with alcohol- and aldehyde-free wipes such as Microbac tissues [BODE Chemie]). The needle and syringe are, of course, sterile.

Because the operator does not come into contact with the needle or the patient’s skin, it is unnecessary to wear sterile gloves. Disposable gloves should be used, however, to protect against contamination with the patient’s blood.

Catheters for draining thyroid cysts and abscesses should be placed under sterile conditions. Sterile drapes, gown, mask, hood, and sterile instrument covers should be used, just as in an operating room.

After the procedure is completed, the transducer is wiped cleaned with a (nonsterile) towel and cleaned with disinfectant wipes.23–25

27.1.7 Procedure

Long-Axis Biopsy Technique

Given the relatively small size of the thyroid gland and its proximity to blood vessels and the larynx, it is helpful to visualize the full length of the biopsy needle. The needle is introduced at the narrow end of the transducer, directing it at a low angle to the skin. Ideally the needle should be constantly visible over its full length as a double echogenic line (▶ Fig. 27.6, ▶ Fig. 27.8b).

Fig. 27.8 Classic “long-axis” technique for biopsy of a suspicious thyroid nodule.

a The right hand holds the 7.5-MHz transducer while the left hand holds the 10-mL syringe on a 20-gauge needle. The needle is introduced at the narrow end of the transducer and is directed at a low angle to the skin.

b Transverse cervical scan displays the needle as a diagonal echogenic line entering the image from the left side and visible anteriorly to the common carotid artery. The needle tip has entered the hypoechoic thyroid nodule.

The needle tip is not always clearly visible in echogenic surroundings, and small back-and-forth movements of the needle can aid visualization. The operator can hold the transducer in either hand, depending on his or her ability to manipulate the syringe and needle with the opposite hand.

Short-Axis Biopsy Technique

In the “short-axis” technique the biopsy needle is introduced at the center of the long edge of the transducer and is directed almost perpendicular to the skin. This technique is sometimes necessary when dealing with small lesions and a difficult access route. It is more difficult because the full length of the needle shaft is not displayed on the screen and the tip can be identified only by rocking the transducer in a “radarlike” sweep (▶ Fig. 27.9a, b; ▶ Fig. 27.10a).

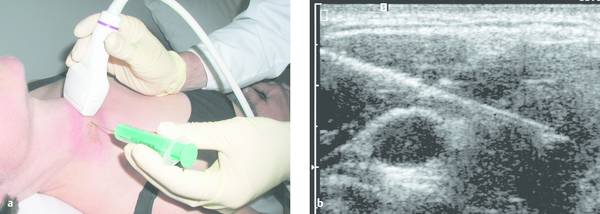

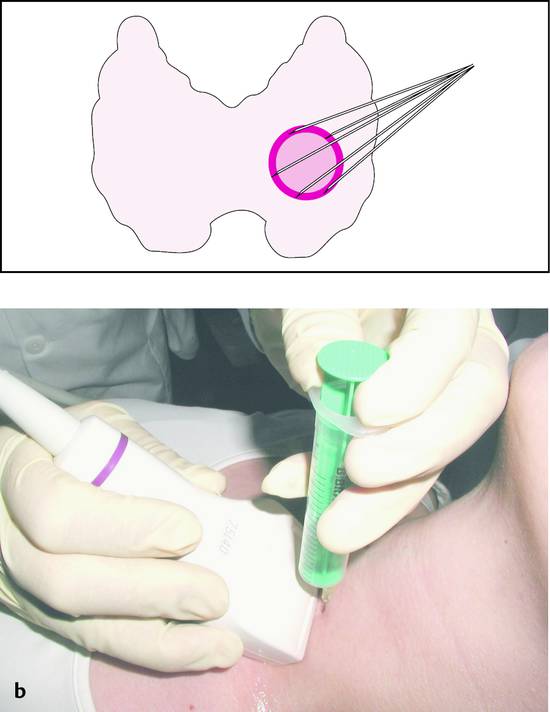

Fig. 27.9 Less common “short-axis” technique for aspirating a thyroid cyst.

a The needle is introduced at the center of the long edge of the transducer.

b The needle tip appears as a high-amplitude echo (upper arrow) with a distal acoustic shadow (lower arrow) within the elliptical cyst, which contains scattered internal echoes. In the moving image, visualization is aided by varying the scan angle and making fast twitching movements of the needle, making the tip easier to identify than in this static image.

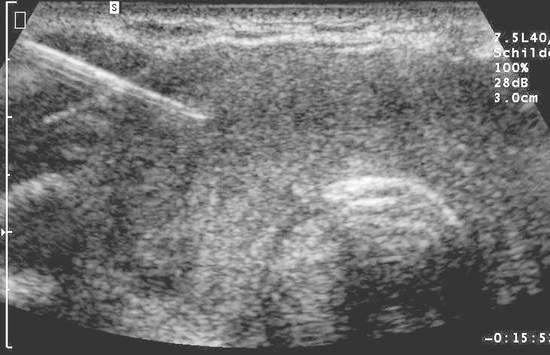

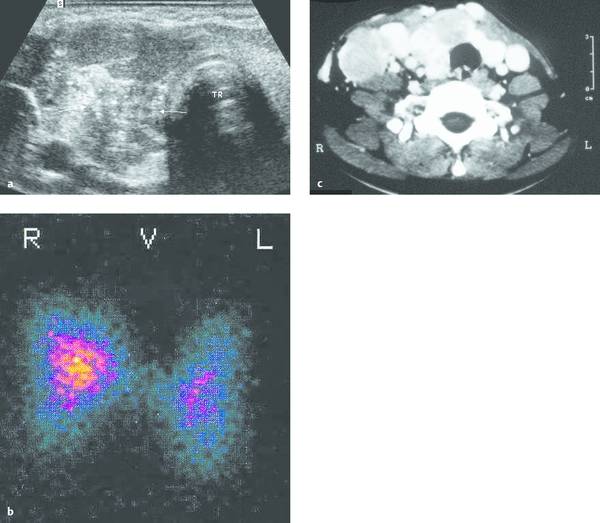

Fig. 27.10 FNA biopsy using the short-axis technique.

a Transverse cervical scan shows the uniformly echogenic normal tissue of the thyroid left lobe on the right side of the image, bordering the trachea (TR). The right lobe has been infiltrated by an inhomogeneous mass (arrows). Small psammomatous body–like echoes of calcium density make it difficult to identify the needle tip, but short twitching movements can define the tip much more clearly in the moving image than in this static image. FNA identified the lesion as mixed follicular papillary thyroid carcinoma.

b Thyroid scintiscan in the same patient appears normal!

c Contrast-enhanced CT was performed elsewhere in the same patient. Note that this type of scan is contraindicated as it interferes with radioiodine therapy after thyroidectomy

Fine needle Aspiration

FNA does not require local anesthesia.26 We prefer the bimanual freehand technique with a long-axis probe placement, as it is economical and can be repeated as often as desired. It also permits the needle to be introduced at any angle.27

When the needle has entered the nodule, the plunger of the syringe is drawn back 2 cm3 to create suction, and the needle is repeatedly advanced and withdrawn 3 or 4 times in a fan-shaped pattern while suction is maintained (▶ Fig. 27.11a, b). It is important to sample the periphery of the nodule, where there should be a higher yield of viable tissue.20

Fig. 27.11

a Diagrammatic representation of fine needle aspiration from the periphery of a thyroid nodule. Suction should be discontinued before the needle is withdrawn from the nodule into normal thyroid tissue.

b Hand position during aspiration: the thumb and index finger of the left hand maintain suction while moving the syringe and needle back and forth under vision.

The plunger should be released to discontinue suction before the needle is withdrawn, or at least by the time aspirated material appears within the syringe barrel (▶ Fig. 27.12). Releasing the suction in this way will minimize the aspiration of extraneous material into the syringe and prevent tumor seeding of the needle tract.

Fig. 27.12 A small amount of blood-tinged aspirate appears inside the barrel of the syringe. The plunger is released, and the syringe is withdrawn without suction.

When the biopsy is completed, the patient places uniform pressure on the puncture site with a sterile pad for several minutes while the physician processes the aspirate.

Preparation of the Aspirate

The operator detaches the syringe from the needle, fills approximately half the syringe with air, and reattaches the needle to the syringe. The needle is then placed bevel-down against the prepared slide, and the harvest is expelled onto the slide in drops. A second slide is used to prepare smears. Further processing of the specimens (air drying or fixed in Merckofix, for example) should be discussed with the cytopathologist. Alcohol fixation of smears should be done immediately after the smears are prepared.

An adequate specimen should include at least six groups of well-preserved thyroid epithelial cells consisting of at least 10 cells each.8

Aspirated cystic fluid is taken immediately in a fresh state to the cytology laboratory for centrifugation. If this is not possible (e.g., at weekend), the specimen should be stored in a refrigerator.

Drill Technique, Fine Needle Nonaspiration

In this technique the biopsy proceeds initially as described above, and the needle tip is watched on the monitor until it reaches the target site. At that point the transducer is set aside and the syringe is stabilized securely with one hand. With the other hand, the operator grasps the syringe by the plunger (while applying little or no suction) and twists it once or twice on its long axis while advancing it slightly. The syringe–needle unit must be held at a constant angle while this is done. The purpose of “drilling” the needle in this way is to sample a core of thyroid tissue while causing minimal tissue trauma. This technique is somewhat more difficult to learn than fine needle aspiration.

One advantage of the drill technique is that it causes less tissue trauma, resulting in the aspiration of less blood.20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree