div class=”ChapterContextInformation”>

3. Advanced Intracranial Vessel Wall Imaging and Future Directions

Keywords

Three-dimensional vessel wall MRIAtherosclerotic diseasePlaqueIntracranial vesselsBlack blood MRIVasculitisIntroduction

Conventional angiographic techniques such as CT angiography, MR angiography, and digital subtraction angiography demonstrate luminal stenosis but are unable to characterize the underlying disease within the vessel wall. Depiction of the vessel wall abnormality improves the ability to distinguish vasculopathies with similar angiographic findings and can offer insight into risk and management of the underlying disease. Vessel wall visualization requires suppression of blood flow most commonly using black blood MRI (BBMRI) sequences [1]. Historically, two-dimensional (2-D) T1 or proton density black blood sequences were developed to characterize the vessel wall of carotid arteries driven partly by access to endarterectomy specimens for comparison with imaging [2, 3]. However, application of 2-D sequences for imaging intracranial vessels is challenging given the smaller size and tortuosity of these vessels. 2-D techniques have a non-isotropic resolution that results in overestimation of vessel wall thickness due to the small size of vessels compared to even the most optimized 2-D voxel size [4]. In addition, achieving contiguous 2-D slices orthogonal to the course of intracranial vessels can be very challenging due to the tortuosity of these vessels [5]. Isotropic 3-D vessel wall MRI (VWMRI) overcomes this challenge and enables characterization of the intracranial vessel wall with reduced partial volume averaging [6]. A detailed explanation of the 3-D high isotropic resolution black blood MRI technique and protocols has been previously reported [1, 7].

In this chapter, we review the role of vessel wall MRI for evaluation of vasculopathies including atherosclerotic disease, vasculitis, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS), dissection, and aneurysms. In addition, we review 4D flow MRI, 4D-CTA, and transcranial Doppler ultrasound.

Intracranial Vasa Vasorum

Vasa vasorum consist of networks of arteries, capillaries, and veins supplying oxygen and nutrients to the walls of larger blood vessels. Intracranial vessels are unique in the paucity of vasa vasorum found in their adventitia under normal conditions, thought to be a consequence of the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid environment [8]. Vasa vasorum may develop within intracranial arteries with age, predominantly at the proximal portions [9], and as a consequence of vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, vasculitis, and aneurysms [8, 10]. Its development has been implicated in promoting inflammatory processes, which can progress to the inner layers [11] leading to the initiation and acceleration of intracranial atherosclerosis [8]. For example, there is a strong association between presence of vasa vasorum and atherosclerotic plaque particularly in thicker intracranial vessels [10]. The relative paucity of intracranial vasa vasorum offers an explanation for the lower frequency of intracranial atherosclerosis compared to coronary and carotid atherosclerosis and higher correlation of extracranial carotid and coronary atherosclerosis compared to intracranial and coronary atherosclerosis [12].

Given the unique features of intracranial vasa vasorum and its implication in intracranial vasculopathies, imaging detection of intracranial vasa vasorum may have an important role in disease diagnosis and prognostication. Intracranial vasa vasorum can be detected by contrast-enhanced MR and CT techniques and is evident by vessel wall enhancement [8, 13].

Intracranial Atherosclerotic Disease

Intracranial atherosclerotic disease (ICAD) is very prevalent and a major cause of ischemic stroke [14]. The estimated prevalence of symptomatic intracranial stenosis varies from 1 in 100,000 for whites to 15 in 100,000 in African Americans in population-based studies [15]. Autopsy studies have noted intracranial atherosclerotic disease to be present in as many as 23% and 80% of people in their 6th and 9th decades of life, respectively [15]. Traditional methods of diagnosing atherosclerosis have been based on measures of luminal narrowing which underestimates plaque burden because of compensatory dilatation (remodeling) to accommodate plaque formation especially early on [6]. In coronary arteries, outward (positive) remodeling can preserve the lumen at a plaque burden as high as 40% of the arterial lumen circumscribed by the internal elastic lamina based on plaque specimen analyses [16]. Negative or inward remodeling results in luminal narrowing and may alter hemodynamics. Although outward remodeling limits the hemodynamic impact of the plaque, it may be associated with increased plaque vulnerability and clinical events as shown in coronary arteries [17, 18].

Imaging Intracranial Atherosclerotic Plaque

Vessel wall magnetic resonance imaging is an effective method for measurement of wall thickness and characterization of pathologic features of the carotid arteries [3] and intracranial vessels [1, 19]. 3D high isotropic resolution black blood MR imaging has made it possible to identify and characterize intracranial atherosclerotic disease [1, 20] and discriminating it from other vasculopathies [7, 21].

A US community-based population study (the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study) estimated the prevalence of having at least one intracranial atherosclerotic plaque to be 34.4% using VWMRI [22] which is higher than previous estimates of intracranial stenosis in population-based studies [15]. In the ARIC study, 10.8% of participants had ICAD with no detectable stenosis [22] which helped to explain the difference in prevalence estimates. Cross-sectional reliability estimates of VWMRI measurements of intracranial atherosclerotic plaque based on 102 repeat scans and 20 inter-reader and 29 intra-reader repeat readings have been shown to range from good to excellent for quantitative measurements (e.g., intracranial vessel lumen, wall thickness) and fair to good for qualitative measurements (plaque presence, ordinal stenosis) [20]. The high reliability is likely a reflection of the reproducibility of 3D imaging and the effect of adequate training for image interpretation, which was heavily emphasized in this study [20].

MR Features of Atherosclerotic Plaque and Identifying Culprit Plaque

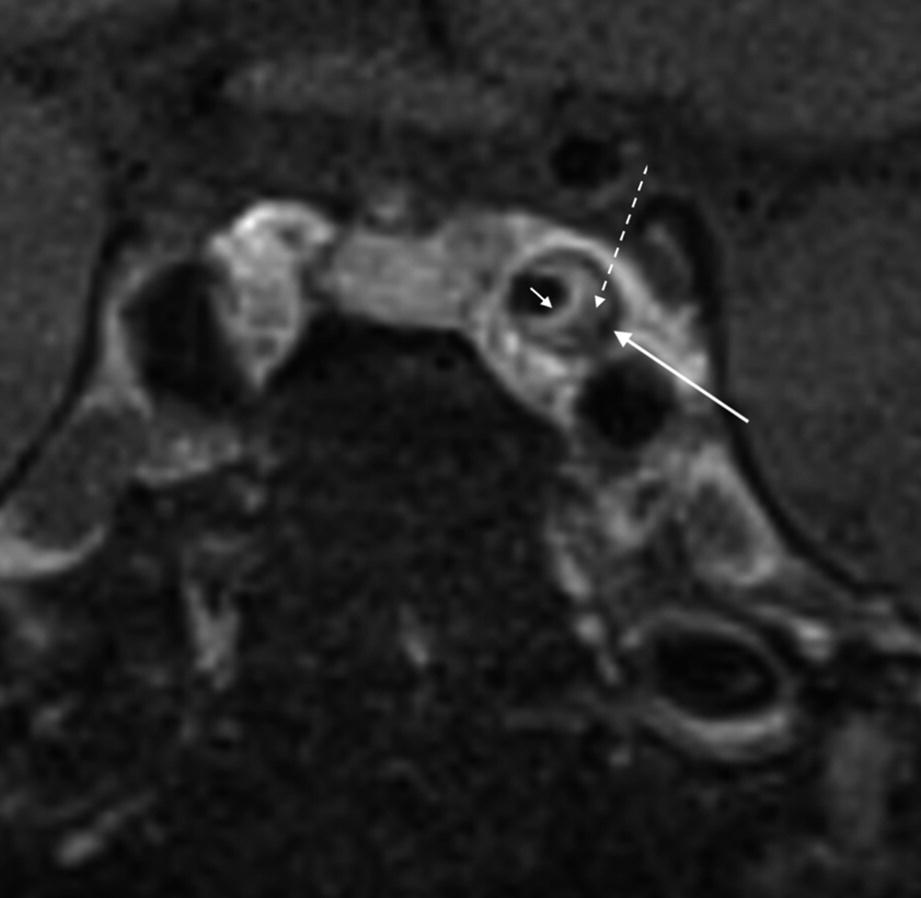

Features of an atherosclerotic plaque involving the cavernous carotid artery with an enhancing fibrous cap (short arrow), lipid core (dotted arrow), and peripheral calcification (long arrow)

VWMRI has been used to characterize vascular remodeling in extracranial carotid [31, 32] and intracranial arteries [6] and has enabled our ability to detect atherosclerosis with no luminal stenosis [33]. These non-stenotic lesions appear to be the strongest risk factor for white matter hyperintensities in patients without intracranial stenoses [34]. Luminal preservation in cervical internal carotid arteries has been shown to occur at plaque burdens up to 62% measured using MRI techniques [31, 32]. Intracranial arteries can also remodel to a high degree as a result of plaque formation with the posterior circulation having a higher capacity for positive remodeling than the anterior circulation [6]. Prevalence of positive remodeling in atherosclerotic plaques in stroke patients was shown to be 29.9% in the anterior circulation versus 54% in the posterior circulation, with lumen patency being maintained in the posterior circulation with plaque burdens up to approximately 55.3% [6]. This may be attributed to differences in hemodynamics (i.e., slower flow in the posterior circulation) and sparse sympathetic innervation of the vertebrobasilar system [6, 35, 36].

Another potential application of VWMRI is determining the location of atherosclerotic plaque relative to a branch artery. Although atherosclerotic plaques tend to arise from arterial wall opposite a branch artery ostium [5, 37, 38], some plaques arise close to the ostia and are associated with increased risk of infarction [38]. Angioplasty can push the atheromatous material from the treated artery to a branch resulting in acute stroke. Determining location of plaque relative to ostium may be useful in intracranial angioplasty risk assessment [39].

Vasculitis

Vasculitides are rare group of diseases defined by inflammation of the vessel wall [8]. Central nervous system vasculitis (CNSV) can be defined as any inflammatory vasculopathy that results in nonatheromatous intracranial vascular inflammation [40]. Primary CNSV is caused by direct involvement of vessels, while secondary vascular inflammation can result from infections, autoimmune processes, tumors, or other processes [40]. Although exact mechanism of involvement of vasa vasorum in vasculitis is not well established, higher prevalence of extracranial vasculitis suggests a role given higher density of vasa vasorum in extracranial arteries [8].

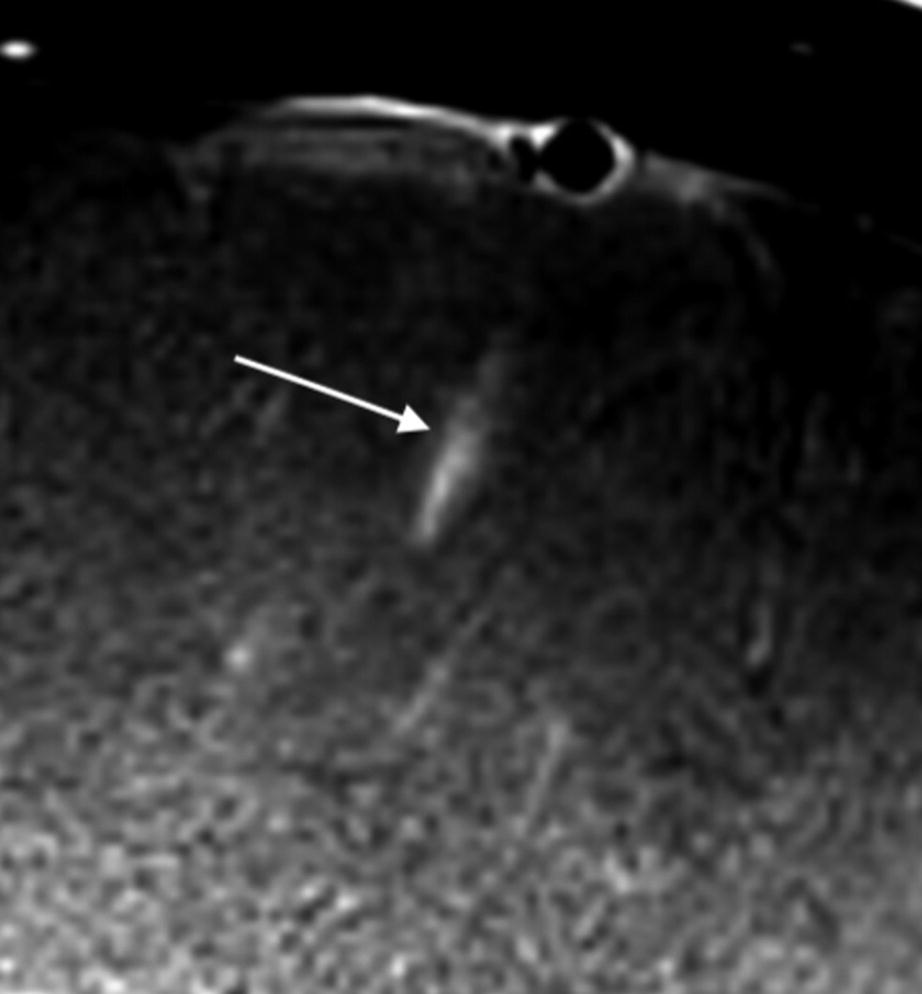

VWMRI appearance of small vessel vasculitis in a patient with clinical and radiological diagnosis of small vessel vasculitis. Contrast-enhanced VWMRI demonstrates peri-adventitial enhancement of an inflamed segment of a vessel seen in long axis (arrow)

Pitfalls of VWMRI for vasculitis include inability to distinguish between transmural inflammation (e.g., primary CNSV) and perivascular inflammation (e.g., sarcoidosis) [40]. In addition, concentric wall thickening after thrombectomy may mimic vasculitis if patient’s history is not known [30].

Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome

Vasospasm results from smooth muscle shortening and increased wall redundancy that can result in a fivefold increase in wall thickness corresponding to 60% luminal narrowing [45, 46]. Arterial wall thickening is a feature of vasospasm on vessel wall imaging [7]. RCVS is characterized by noninflammatory reversible multifocal cerebral vasoconstriction associated with recurrent thunderclap headaches that resolve spontaneously within 3 months [47, 48]. It is an underdiagnosed entity and may lead to complications such as posterior reversible encephalopathy, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and ischemic infarcts [48, 49]. Timely distinction of RCVS from its top differential consideration, vasculitis, is essential since treatment strategies are very different. In particular, the appropriate management of vasculitis by steroids carries a significant morbidity [42].

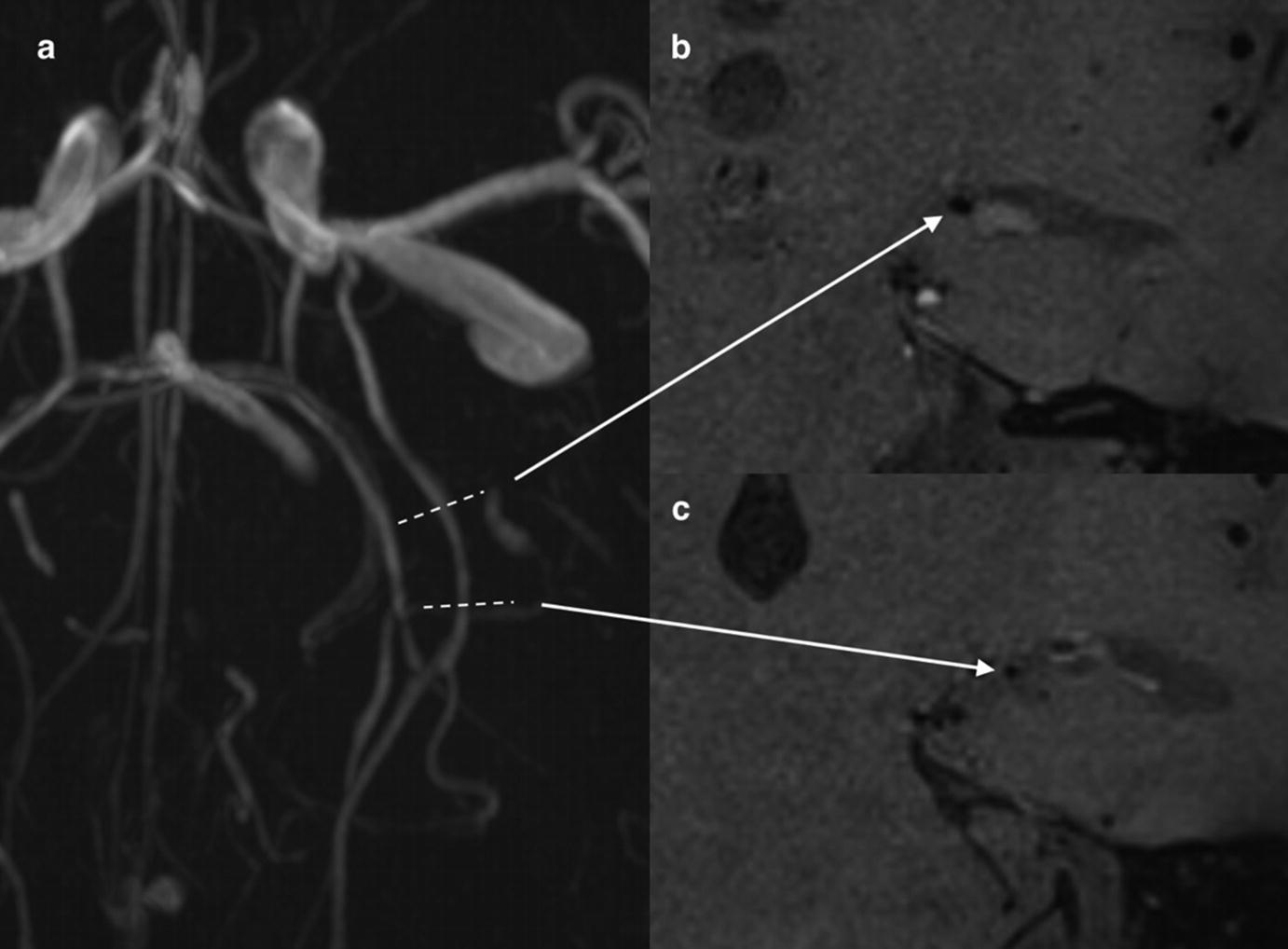

VWMRI in a 5-year-old with RCVS. Time-of-flight MR angiography (a) demonstrates focal narrowing of duplicated left posterior cerebral artery. VWMRI shows cross-sectional appearance of normal segment of the vessel (b) compared to narrowed segment (c). No peri-adventitial or vessel wall enhancement in region of focal narrowing of the left posterior cerebral artery is seen (c)

Arterial Dissection

Chronic arterial dissection of the horizontal petrous segment of the carotid artery. Non-contrast (a) and contrast-enhanced (b) VWMR images through the short axis of the artery demonstrate enhancement of the vessel wall and flap separating the false lumen (arrow) from the true lumen

Aneurysms

There is ongoing debate regarding the pathophysiology that underlies aneurysm growth and rupture. Vasa vasorum are reported to be present in large (4 mm or larger) saccular aneurysms and fusiform aneurysms and have been implicated in growth and rupture of these lesions [8]. Repetitive intramural hemorrhage from vasa vasorum and reabsorption of blood is believed to induce inflammation and proliferation of microvessels that are prone to re-bleeding. This is postulated to result in enlargement and weakening/rupture of the aneurysm wall [52].

There is a growing body of evidence that supports the use of VWMRI for evaluating aneurysms [53, 54]. Contrast enhancement in the wall of unstable aneurysms has been reported and may be due to a loss of vasa vasorum integrity, intimal angiogenesis, and inflammatory activity [8, 55, 56]. Two recent histological studies of unruptured intracranial aneurysms revealed associations of aneurysm wall enhancement on VWMRI with higher macrophage infiltration, increased cellularity, neovascularization, and a thicker wall of the aneurysm [57, 58].

Retrospective studies have reported thick peripheral enhancement of ruptured aneurysms in the setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage, while unruptured aneurysms do not enhance [56, 59, 60]. It is noteworthy that in these retrospective studies, enhancement may represent inflammatory changes related to the rupture itself [23].

Aneurysm wall enhancement may also be a predictor of progression. In prospective studies of asymptomatic patients, enlarging or morphologically changing aneurysms demonstrate thick peripheral enhancement compared to little to no enhancement in stable asymptomatic aneurysms suggesting a potential role of VWMRI for treatment planning [60, 61]. Circumferential aneurysm wall enhancement >1 mm in thickness is shown to have the highest specificity and negative predictive value for differentiating between stable and unstable aneurysms [61]. In addition, a stronger degree of enhancement was associated with a higher clinical risk for rupture based on PHASES (population, hypertension, age, size, earlier subarachnoid hemorrhage, and size) score [62]. A meta-analysis of five retrospective and prospective studies with 492 subjects showed a significant and independent association of aneurysm wall enhancement with aneurysm rupture [63].

Potential use of VWMRI in detecting the source of hemorrhage in angiogram negative non-perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage has also been studied with no change in patient management [64]. Further investigation is warranted to understand the mechanism of aneurysm rupture and instability before contrast enhancement can be used as a marker for impending rupture.

4D Flow MRI

New applications of phase-contrast MRI have emerged to noninvasively evaluate blood flow qualitatively (flow visualization and direction) and quantitatively (velocity, pressure, wall shear stress) [65]. Hemodynamic parameters such as flow patterns, location of flow impact on aneurysm wall, size of impact zone, and wall shear stress (WSS) are of particular interest in assessing risk of aneurysm growth and rupture [66]. Low WSS and high oscillatory shear index are thought to initiate inflammatory cell-mediated remodeling in large aneurysms, while high WSS and positive WSS gradients can facilitate mural cell-mediated remodeling in small or secondary bleb aneurysms [66]. Both of these pathways may lead to aneurysm growth and rupture.

4D flow MRI has also been used to measure flow in arteriovenous malformations (AVM), specifically in arterial feeders along with arteries adjacent and contralateral to the AVM for a global hemodynamic evaluation for embolization planning [67, 68]. Velocity-derived flow-tracking cartography can help with functional assessment of the AVM with high reliability and good to excellent agreement with DSA for identification of shunt location and arterial feeders and evaluation of retrograde flow in dural venous sinuses or cortical veins [65]. Virtual MR flow-tracking cartography can classify dural arteriovenous fistulas (AVF) similar to catheter angiography (Cognard classification) providing risk stratification of bleeding based on assessment of venous drainage [69].

4D-CTA

In 4D CT angiography (4D-CTA), images are obtained throughout intravenous administration of contrast bolus using continuous or noncontinuous acquisition [70]. 4D-CTA is shown to be comparable to DSA in detecting and grading of cerebral AVMs [71, 72] and dural AVFs [73, 74]. In the work-up of acute ischemic stroke, 4D-CTA has been shown to be superior to conventional CTA for characterizing the extent and dynamics of collateral flow [75] and intracranial thrombus burden [76]. 4D-CTA has been comparable with DSA in discriminating antegrade flow from retrograde flow across an occluded vessel helping to predict rate of recanalization following intravenous thrombolysis which is correlated with antegrade flow [77]. Characterization of collateral flow also helps with prognostication of clinical outcome after ischemic stroke and rate of complications such as hemorrhagic transformation [70, 78].

Transcranial Doppler Sonography

Transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD) is a noninvasive ultrasound technique that can be used at the bedside to detect and localize intracranial arterial narrowing or occlusion. For detecting middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion, TCD has greater than a 90% sensitivity and its specificity approximates that of CTA [79]. TCD has lower sensitivity than CTA for detection of basilar or carotid terminus thrombus [79]. In addition to establishing patency, TCD can provide complementary information to CTA such as visualizing real-time embolization, presence of microemboli, and alternating flow signals indicative of steal phenomenon [79]. Furthermore, TCD can detect restenosis or re-occlusion after thrombolysis or thrombectomy [80]. Main drawbacks of its use are lack of adequate sonographic window through the temporal bone and limited availability of experienced technician or clinician [81].

Conclusions

In summary, the current literature supports an important role for intracranial vessel wall imaging in differentiating etiologies of intracranial vessel wall narrowing such as atherosclerosis, vasospasm, vasculitis, and arterial dissection. In addition, it can be useful for identification of non-stenotic lesions that would escape angiographic detection. Potential applications include risk stratification for atherosclerotic plaques and identifying actively inflamed lesions in vasculitis which could be useful for directing targeted biopsies of vessels. Future applications of VWMRI might also include risk stratification of aneurysms for rupture or growth. 4D flow technique is a useful adjunct for assessment of flow dynamics and rupture risk of aneurysms, AVMs, and dural arteriovenous fistulas and may be useful in treatment planning. Further investigations are warranted in larger samples for validation of clinical use of vessel wall MR and 4D MR/CT.