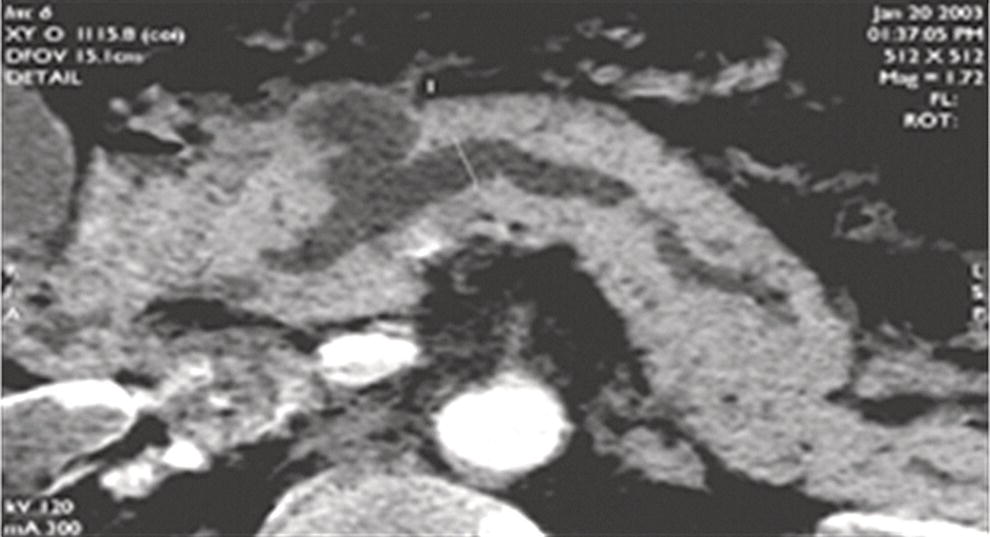

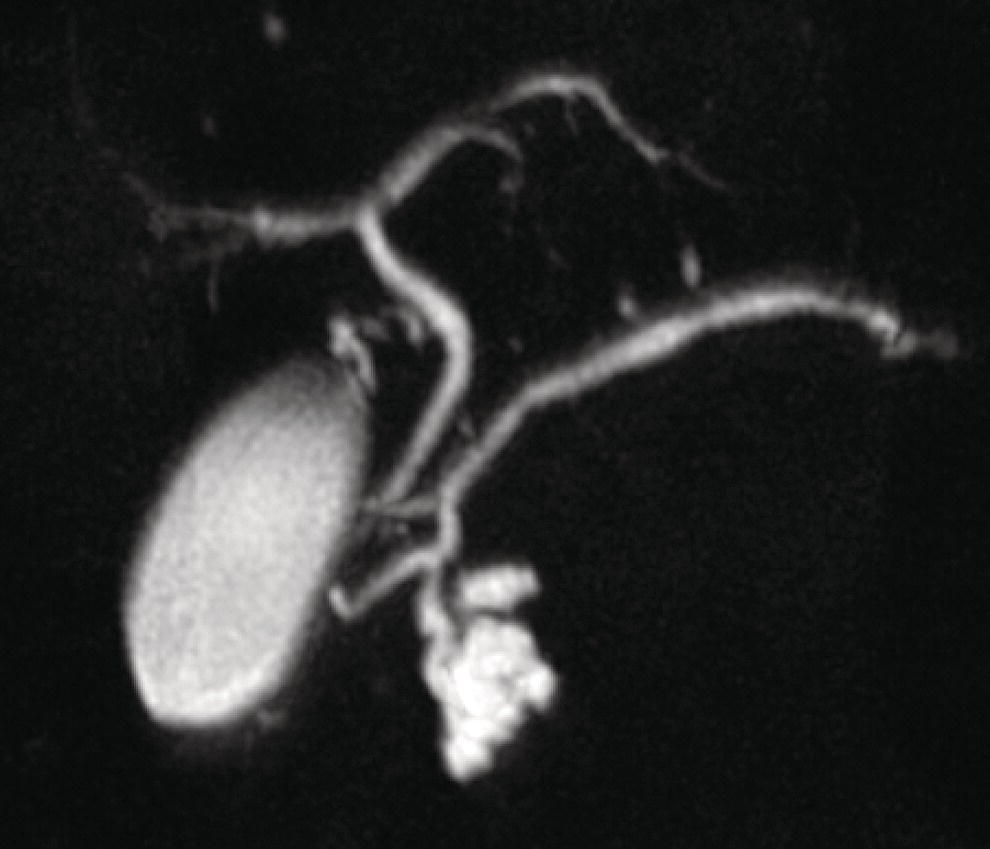

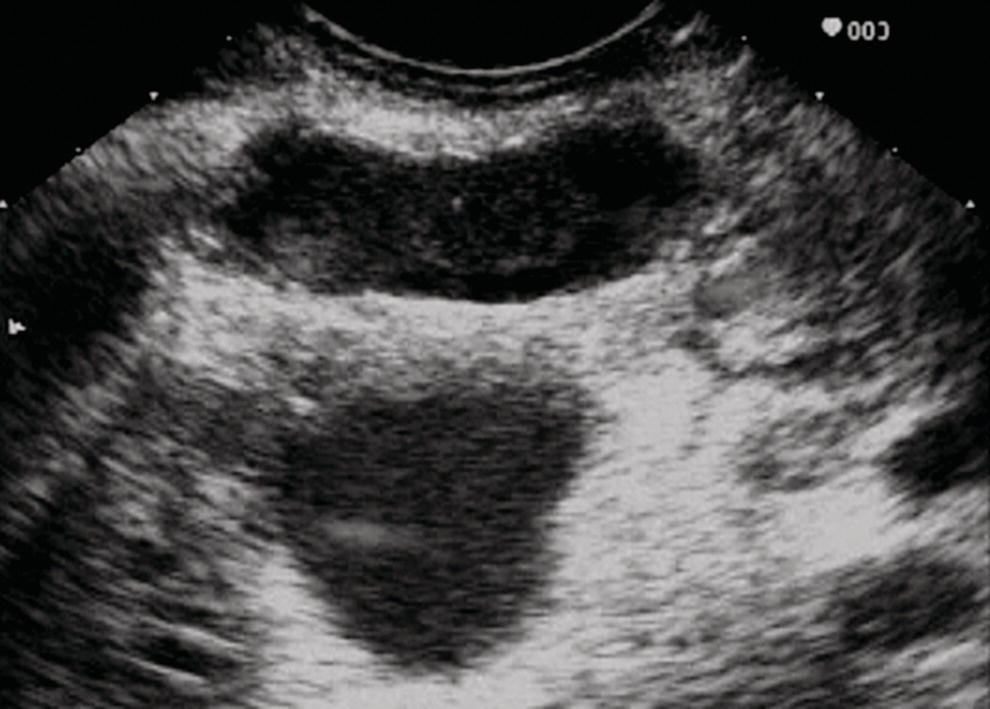

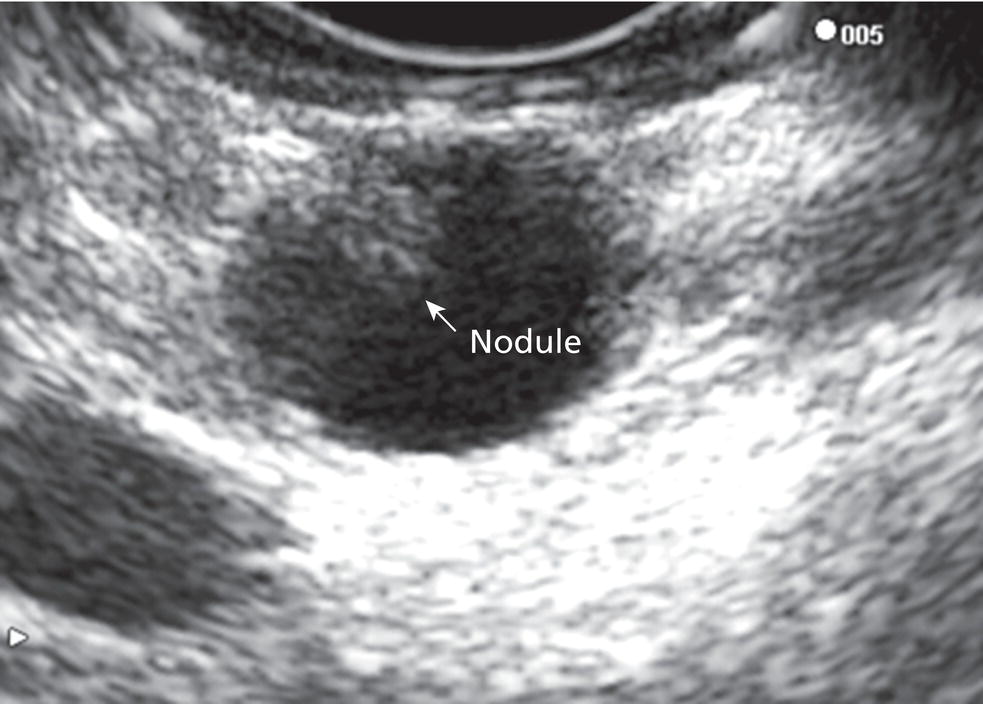

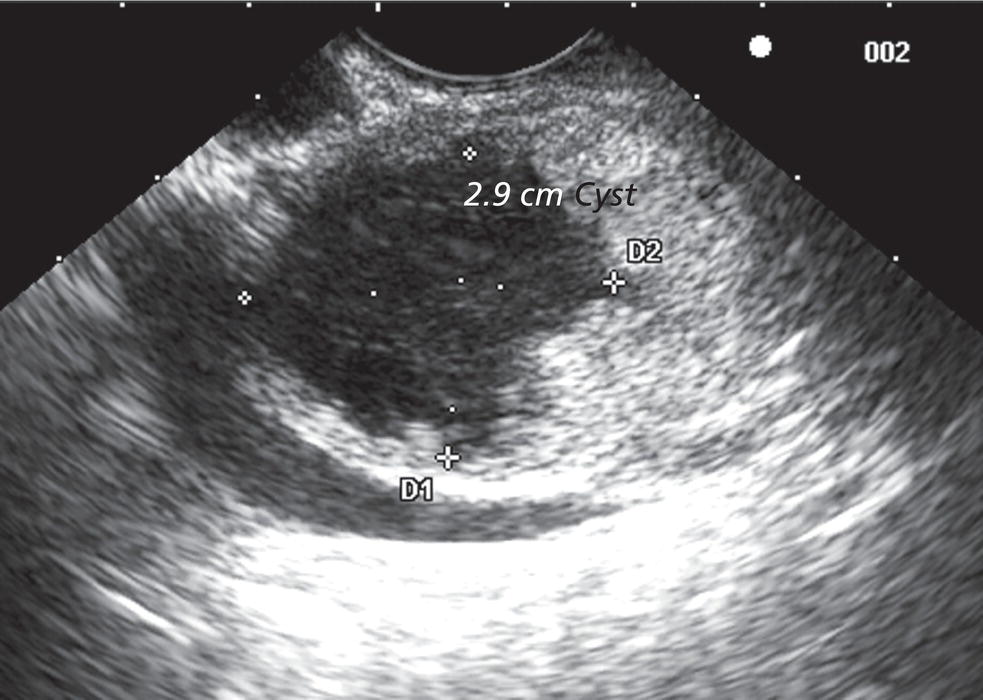

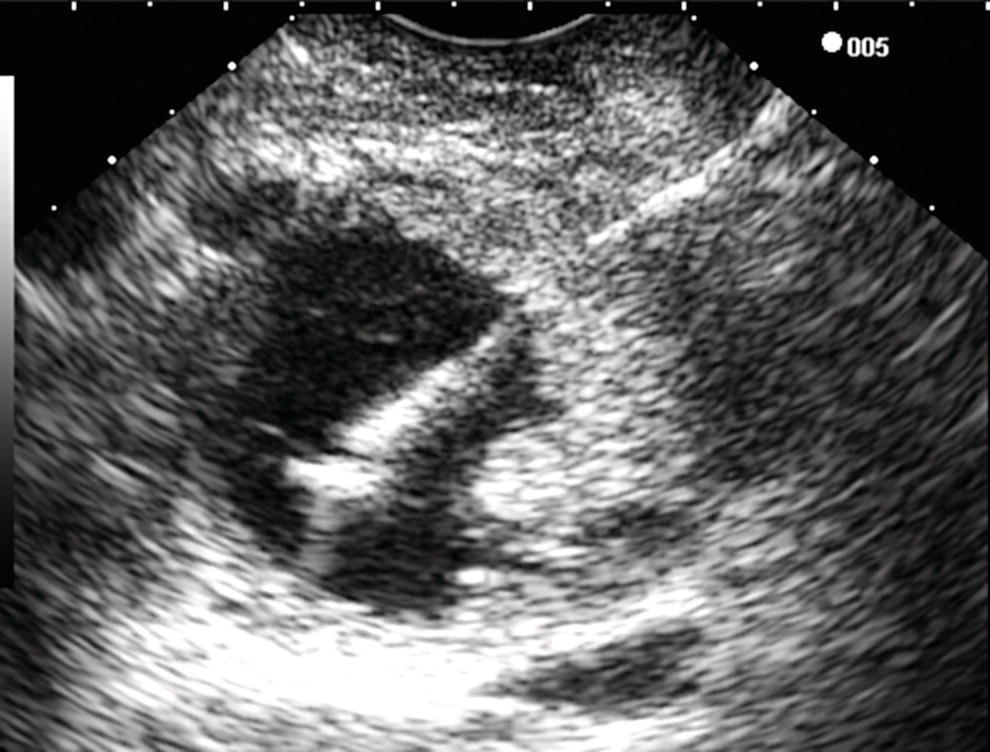

William R. Brugge Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) have emerged as the most common mucinous cystic neoplasm and represent a significant clinical entity. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is an important tool for the diagnosis and management of IPMNs. IPMNs represent a premalignant pancreatic lesion generally characterized by proliferation of the mucinous epithelium with varying degrees of ductal and cystic dilatation. These papillary lesions typically involve the main pancreatic duct with or without side branch involvement. Based on the differential location of the tumor, they can be classified into three types: branch‐duct IPMN, main‐duct IPMN, and mixed IPMN. IPMNs can further be described according to a continuum of cellular atypia similar to that of colorectal cancer: benign (adenoma/low‐grade dysplasia), borderline (moderate dysplasia), and malignant (ranging from carcinoma in situ/high‐grade dysplasia to invasive carcinoma). Several studies have suggested that main‐duct IPMNs are associated with higher grade of histology and more rapid growth, compared with branch‐duct lesions, which are felt to represent more indolent disease. The exact rate of cell transition from benign to malignant is not clear, although the progression to invasive disease in main‐duct IPMN has been estimated to range from five to seven years. There have been estimates of the rate of malignant degeneration ranging from 0.5 to 1.0% per year. Overall, invasive carcinoma arising in association with IPMN has a better prognosis than conventional ductal adenocarcinoma; however, when metastatic, its prognosis is as poor as that of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Symptoms for IPMN are vague and often nonspecific, and most patients are asymptomatic, especially those with small (≤3 cm) lesions. When symptomatic, patients usually present with abdominal pain which may represent recurrent pancreatitis. Patients commonly present in the sixth to seventh decade, with the mean age at diagnosis being 65 years. Obvious main‐duct lesions are more likely to present with symptoms masquerading as chronic pancreatitis and other features. Gradual distension of the pancreatic duct due to excess mucin secretion induces recurrent abdominal pain and symptoms of pancreatitis secondary to main‐duct IPMN. Because of the presentation and appearance, IPMNs have in fact been misdiagnosed as chronic pancreatitis in the past. Multiple modalities can be used to image and stage IPMNs, including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Using any one of the modalities can provide diagnostic features, evidence of malignancy, and staging information. The resolution of multidetector CT (MDCT) has improved dramatically in the past years. The quality of the digital displays provides excellent imaging of the pancreas and the ductal system. Communication between a cystic branch‐duct lesion and the main duct is well visualized on thin‐section MDCT. With these improvements, CT provides excellent imaging of IPMN including important features such as septations and nodules (Figure 26.1). MRCP has also evolved rapidly in the imaging of the pancreas. Breath‐hold MRCP is less dependent on patient cooperation. Studies have shown this technique to be even more effective in detecting connections with the main pancreatic duct than MDCT (Figure 26.2). The use of intravenous secretin improves the quality of MRCP and visualization of the extent of duct involvement. For IPMN evaluation, whether MDCT or MRCP is used, a dedicated pancreatic imaging protocol should be adhered to. Figure 26.1 Reformatted computed tomography scan demonstrating a side‐branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Figure 26.2 Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography demonstrating a side‐branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm in the head of the pancreas. Endoscopic ultrasound evaluation can be particularly helpful if there is diagnostic uncertainty, although it is not the preferred first‐line imaging modality for IPMN. It is also helpful in cases where surgical risk is high, and verification of malignancy is needed before resection, such as in older patients or those with high comorbidities. Endoscopic ultrasound can provide detailed imaging of main‐duct IPMN, side‐branch disease, and combined duct disease. The EUS findings of IPMN include cystic lesions, a dilated main pancreatic duct, and/or a parenchymal mass (Figures 26.3–26.5). The diagnosis is usually readily made once multiple cystic lesions have been demonstrated. However, the findings of a viscous fluid during fine needle aspiration (FNA) will confirm the diagnosis. With the diagnosis established, attention should turn towards detection of malignancy. The most obvious targets are a dilated main duct, a nodule arising within a cyst, and a pancreatic mass (Figure 26.6). Of course, signs of metastatic disease such as liver metastases, lymphadenopathy, and ascites are very important findings. Fine needle aspiration of the main pancreatic duct is performed with a 22‐gauge needle usually from the gastric body. Pancreatic duct juice is readily aspirated from the main duct. Care should be taken in the aspiration of nodules, because of the risk of bleeding and contaminating the cytologic specimen. The results of FNA should be used to assist in the planning of resection. For example, in the presence of multiple cysts, representative lesions in the head, body, and tail should be used to determine the type of resection. Figure 26.3 Linear endoscopic ultrasound image demonstrating a dilated main pancreatic duct, indicative of a main‐duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Figure 26.4 Linear endoscopic ultrasound image revealing a small cystic lesion with a mural nodule. Figure 26.5 Linear endoscopic ultrasound image of a malignant‐appearing 2.9‐cm cystic lesion, including an adjacent mass. Figure 26.6 Fine needle aspiration of a malignant cystic mass. Figure 26.7 International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) algorithm for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). Cytologic material from aspirated fluid is often inconclusive for IPMN. However, cyst fluid tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen (CA) 72‐4, are important for establishing the mucinous origin of the cyst. KRAS is also a very useful marker for a mucinous lesion. The diagnosis of malignancy is usually established with the finding of malignant cytology, aspirated from a cyst, nodule, or mass. Many IPMNs need not be resected and can be followed conservatively due to their low risk for malignancy and slow progression toward invasive cancer. These include IPMNs without symptoms, without main‐duct dilatation (>6 mm), without mural nodules, without thick walls/septations, or less than 3 cm in size. Consensus follow‐up guidelines have been formulated by the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP): yearly follow‐up is recommended for lesions less than 1 cm in size; follow up every 6–12 months is advisable for lesions of 1–2 cm; and follow‐up every three to six months is indicated for lesions larger than 2 cm (Figure 26.7). If symptoms arise, or if any of the above limits regarding size, dilatation, or solid components are surpassed on follow‐up, resection is suggested. A greater than 1 cm increase in lesion size over a year is generally considered significant for malignancy. If minimal or no change is observed after two years, then the time frame between follow‐up studies can be extended. An algorithm for observing small (≤3 cm) IPMN has been proposed. When deciding which modality to use, follow‐up imaging should be tailored further by considering radiation concerns relative to age. It may be advisable to monitor IPMN patients who are less than 40 years old with MRI and those who are over 40 years old with CT. Steps should still be taken to minimize radiation risk since the cumulative exposure from prolonged and repeated radiological follow‐up may be substantial.

26

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms: The Role of EUS

Introduction

Clinical features

Role of imaging

Cross‐sectional imaging

Endoscopic ultrasound evaluation

Management of small IPMN (≤3 cm)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree