Chapter 28 Kidney, Bladder, Prostate, Testis, Urethra, Penis

Kidney

Anatomy

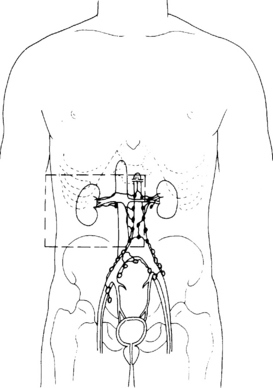

The kidneys lie retroperitoneally on the posterior abdominal wall. They are approximately 11 cm long and 6 cm wide in adults. The left kidney is 1 cm higher than the right. The right kidney is related in front to the liver, the second part of the duodenum and the ascending colon. In front of the left kidney are the stomach, the pancreas, descending colon and the spleen. On the top of each kidney lies an adrenal gland. Behind the kidneys lie the diaphragm and the 12th rib. On the medial side of the kidney there is an opening, the hilum, through which pass the renal artery and vein, and the ureter. The renal vein drains into the inferior vena cava. The lymphatic drainage is to the para-aortic nodes. The anatomical relationships are shown in Figure 28.1.

Pathology

The three principal malignant tumours of the kidney are Wilms’ tumour (nephroblastoma) in children (described in Chapter 33), renal cell adenocarcinoma (also called clear cell carcinoma, hypernephroma and Grawitz’s tumour) and transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. Adenocarcinoma arising from the renal tubules accounts for 80% of tumours. Macroscopically, the tumour appears as a yellowish vascular mass. Microscopically, the tumour cells are large with a foamy or clear appearance to the cytoplasm. The nucleus is small, central and densely staining.

Investigation and staging

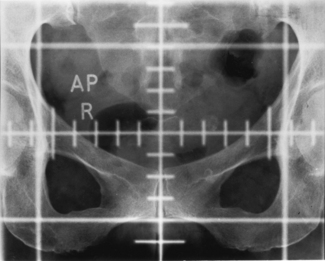

The urine may contain frank or microscopic evidence of blood. Urine cytology may show malignant cells. The most important investigation is an intravenous urogram (IVU), which may show distortion of the calyces (the channels that drain urine to the renal pelvis and are outlined by the contrast medium) by the tumour. Calcification within the tumour may be visible on plain radiographs. Ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scanning (Figure 28.2) are helpful in distinguishing between solid and cystic renal masses. Ultrasound may show extension of tumour into the renal vein or inferior vena cava. CT scanning of the chest, abdomen and pelvis may show direct tumour spread, venous and lymph node involvement and soft tissue metastases in liver and lung. Angiography is an invasive procedure and its use is diminishing. It still has a role in demonstrating the renal artery and new vessel formation when the kidney is to be embolized (i.e. material introduced into the renal arterial to cut off its blood supply and cause death of part or the whole of the kidney). Bone metastases are typically osteolytic (Figure 28.3).

Figure 28.3 Radiograph showing osteolytic metastasis of the vertebral body from renal cell carcinoma.

No staging system for renal cell cancer has universal acceptance. The UICC 1997 TNM classification is shown in Table 28.1.

Table 28.1 TNM staging of primary renal tumours

| Stage | Clinical findings |

|---|---|

| Tumour | |

| T0 | No tumour |

| T1 | Tumour 7.0 cm or less in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney |

| T2 | Tumour more than 7.0 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney |

| T3 | Tumour extends into major veins or invades adrenal gland or perinephric tissues but not beyond Gerota’s fascia |

| T3a | Tumour invades adrenal gland or perinephric tissues but not beyond Gerota’s fascia |

| T3b | Tumour grossly extends into renal vein(s) or vena cava below diaphragm |

| T3c | Tumour grossly extends into vena cava above diaphragm |

| T4 | Tumour extends beyond Gerota’s fascia |

| Tx | Primary tumour cannot be assessed |

| Nodes | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in single regional lymph node |

| N2 | Metastasis in more than one regional lymph node |

| Nx | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| Metastases | |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

| Mx | Distant metastases cannot be assessed |

| Histological grading | |

| G1 | Well differentiated |

| G2 | Moderately differentiated |

| G3–4 | Poorly differentiated/undifferentiated |

| Gx | Grade of differentiation cannot be assessed |

Treatment

Bladder

Anatomy

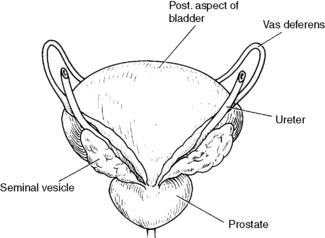

The bladder is related anteriorly to the pubic symphysis, superiorly to the small intestine and sigmoid colon, laterally to the levator ani muscle, inferiorly to the prostate gland and posteriorly to the rectum, vas deferens and seminal vesicles (see Figure 28.7) in the male and to the vagina and cervix in the female. At cystoscopy, the bladder mucosa and ureteric orifices can be inspected. Lymphatic drainage is to the iliac and para-aortic nodes.

Aetiology

In the majority of cases of bladder cancer, the aetiology is unknown. However, as discussed in Chapter 14, occupational exposure to certain carcinogens has accounted for some cases. The production of aniline dyes and processing of rubber are associated with 2-naphthylamine, now recognized as a procarcinogen. Workers in these industries are now offered regular cytological examination of urine to detect abnormalities or tumours at an early stage.

Macroscopic appearance

Solid carcinoma is nodular, often ulcerated, grows more rapidly and infiltrates early.

Investigation and staging

Cystourethroscopy

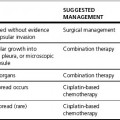

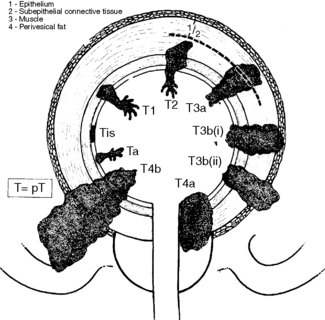

Clinical staging of bladder cancer is according to the TNM classification (Figure 28.4 and Table 28.2).

Figure 28.4 T staging of bladder cancer – UICC classification.

(Reproduced with permission from Hermanek P, Hutter R V P and Sobin L H (eds) 1997 International Union Against Cancer TNM Atlas. Illustrated guide to the TNM classification of malignant tumours, 4th edn, Springer-Verlag)

Table 28.2 TNM staging of bladder cancer

| Stage | Clinical findings |

|---|---|

| Tumour | |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| Ta | Papillary non-invasive carcinoma |

| T1 | Invasion into submucosa but not beyond the lamina propria |

| T2a | Invasion into superficial detrusor muscle |

| T2b | Invasion into deep detrusor muscle |

| T3a | Invasion into perivesicular tissues microscopically |

| T3b | Invasion into perivesicular tissues macroscopically |

| T4a | Invasion of prostate or vagina |

| T4b | Invasion of pelvic side-wall or abdominal wall |

| Nodes | |

| N0 | No evidence of nodal involvement |

| N1 | Single node <2 cm diameter |

| N2 | Single nodal metastasis 2–5 cm diameter or multiple nodes none exceeding 5 cm |

| N3 | Node >5 cm |

| Metastases | |

| M0 | No metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

Treatment

Invasive bladder cancer (T2 and T3)

Surgery and radiotherapy are the standard treatments for invasive bladder cancer.

Adenocarcinoma and squamous carcinoma of the bladder

Neither of these is very radiosensitive and they are better treated by cystectomy.

Radical radiotherapy

The following are criteria for accepting patients for radical radiotherapy:

• age <80 years (unless particularly fit)

• adequate general medical condition

• no inflammatory bowel disease or symptomatic adhesions

• single tumour <7 cm maximum diameter

Radiation planning technique

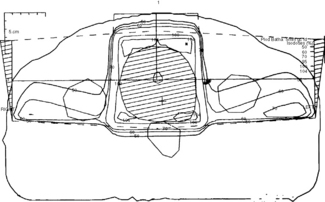

The tumour is localized by a CT planning scan and has replaced using a cystogram (Figure 28.5).

CT planning allows greater definition of the planning target volume (PTV). The patient is planned in the same position on the CT scanner as on the simulator and treatment couches (supine with feet in foot stocks and hands by the side). On the planning computer, the width of the target volume to encompass the tumour with a 1–2 cm margin is chosen. The superior and inferior target volume being 1 cm above and below the upper and lower limits of the bladder. It is common practice to cover the prostatic urethra in the PTV in view of the risk of local recurrence. The position of the rectum and femoral heads are marked on the computer and translated to the treatment plan. An open anterior and two lateral wedged or posterior oblique wedged fields are used, treating isocentrically (Figure 28.6). A direct lateral field is preferred at our institution to reduce rectal doses in view of the sharp fall-off of the field. With high-energy photon beams such as 15 MV, femoral-head doses are kept below 50% of the tumour dose. The use of conformal therapy techniques is routine and improves treatment-related morbidity in addition to possible dose escalation in the future. IMRT is increasingly being used to treat patients at risk of pelvic lymph-node involvement in addition; whether this improves survival however is unproven.

Dose and energy

55 Gy in 20 daily fractions over 4 weeks (9–16 MV photons)

64 Gy in 32 daily fractions over 6.5 weeks (9–16 MV photons).