CHAPTER 11 Imaging the lumbar spine for disc disease and stenosis has evolved in the past 30 years from predominantly myelography-oriented examinations to plain computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations. Although few differences between CT and MRI scanning have been noted concerning diagnostic accuracy in the lumbar spine, MRI examination will give more information and a more complete anatomic depiction than will CT examination.1,2 There are a host of things that can be seen on an MRI study that cannot be seen with CT, yet it remains to be seen if the additional information afforded by an MRI examination will prove to be clinically useful. For example, MRI scanning can determine whether a disc is degenerated by showing loss of signal on T2-weighted images (Figure 11-1). CT scanning cannot give this information, but it hardly matters because no treatment is currently given solely for a degenerated disc. In fact, degenerative discs have been reported in asymptomatic children who deny a history of back pain.3 Nevertheless, MRI has evolved as the imaging procedure of choice for the lumbar spine. FIGURE 11-1 To achieve a high degree of accuracy it is imperative that the proper imaging protocol be observed. Thin-section axial images (4 or 5 mm) should be obtained from the midbody of L3 to the midbody of S1. Angling of the plane of imaging to be parallel to the discs is not necessary (Figure 11-2), and contiguous images without skip areas are considered mandatory (Figure 11-3). Even though sagittal images will be obtained, a host of entities are more easily identified on the axial images than on the sagittal ones. These include migrated free disc fragments, spondylolysis (pars breaks), conjoined nerve roots, the facets, the neuroforamen, the lateral recesses, and intraspinal synovial cysts. We looked at 103 consecutive spine MRI studies4 in which we obtained our standard axial and sagittal T1- and T2-weighted sequences; the axial cuts were contiguous, stacked images without gaps or angling. In addition we obtained axial images that were angled parallel to the discs and covered only the disc spaces, thereby leaving a gap between one level and the next (see Figure 11-2). The angled axial images were combined with the sagittal images and evaluated for free disc fragments and pars breaks and were then compared with the original interpretations, which had the stacked axials and the sagittals. Our standard imaging protocol found 15 cases of spondylolysis and 8 free disc fragments. The angled axial protocol showed only 8 cases of spondylolysis and 3 free fragments, even though the sagittal images were available. We missed three fourths of the free fragments! These patients would likely have all had failed surgery with the angled axial protocol. There’s no reason I’ve ever heard of for angling the axial cuts and leaving gaps, yet about one third of all the consult spine cases I look at use this protocol. I think it’s the number one cause of missed diagnoses in spine imaging. FIGURE 11-2 FIGURE 11-3 Terminology plays a large role in how radiologists describe disc bulges or protrusions. Since the advent of CT in the 1970s, disc bulges have been described by their morphology. A broad-based disc bulge was said to be a bulging annulus fibrosus, whereas a focal disc bulge was called a herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) (Figure 11-4). This is no longer the accepted terminology. FIGURE 11-4 Although no universally accepted classification of disc disease is present, most agree on something like the following: a broad-based disc bulge is called a bulge; a focal bulge is called a protrusion; a piece of disc that has migrated from the parent disc is a free fragment or sequestration. The term HNP is no longer considered acceptable. More significantly, most surgeons do not care what name is applied to a disc bulge—they do not treat a bulging annulus any differently than a protrusion. They treat the patient’s symptoms and have to decide whether the disc bulge is responsible for those symptoms. It has been reported in multiple studies that from 10% to 25% of asymptomatic young people have disc bulges or protrusions5; hence just seeing a disc bulge on a CT or MRI scan does not mean it is clinically significant. One of the most widely used classifications has the terms protrusion, extrusion, and extruded as the basis for describing the type of disc bulge present. I have seen this terminology cause misadventures for patients because it was either used incorrectly by the radiologist or not understood by the surgeon. In this classification a protrusion is a focal disc bulge with a wide neck or base (Figure 11-5, A); an extrusion is a focal bulge with a narrow neck or base (Figure 11-5, B); and an extruded disc is a free disc fragment (Figure 11-5, C). Surgeons don’t treat a patient with a protrusion any differently than one with an extrusion; it’s an artificial distinction based solely on the neck width of the bulge. If that’s all it were, so what, but it’s much more significant, because of the term extruded, which is a free fragment. Missing a free disc fragment is one of the leading causes of failed back surgery, and identifying it will guide the surgeon to search for it and remove it. I have seen several cases in which the terms extrusion and extruded were misused or not understood and patients had free fragments left behind (the surgeon didn’t realize the term extruded meant a free fragment), and in others, the surgeon searched for a free fragment when there was none because the term extruded was incorrectly applied. Because there is no clinical or surgical difference between having a protrusion or an extrusion and surgical mistakes can occur when this terminology is used, I do not let my residents and fellows use these terms. FIGURE 11-5 MRI has a high degree of accuracy in delineating disc protrusions and showing if neural tissue is impressed (Figure 11-6). MRI scans can also show if annular fibers of the disc are disrupted (Figure 11-7)—a so-called HIZ (high-intensity zone). Although annular tears can’t be diagnosed on the basis of CT examination, clinicians do not currently treat them surgically. The annulus is innervated by the sinuvertebral nerve, which goes to the dorsal root ganglion and can mimic a focal disc protrusion at that level. They can cause back pain and even sciatica (buttock and leg pain), but they typically resolve with conservative management. FIGURE 11-6 FIGURE 11-7 A type of disc abnormality that is critical to diagnose is the free fragment or sequestration. Missed free fragments are one of the most common causes of failed back surgery.6 The preoperative diagnosis of a free fragment means the surgeon needs to explore more cephalad or caudally during the surgery to remove the free fragment. Because free fragments can be very difficult to diagnose clinically, imaging is critical in the evaluation of the spine for any patient contemplating surgery. At times it can be difficult to be absolutely certain as to whether or not a disc that lies above or below the disc space is still attached to the parent disc or is really “free.” As long as disc material is above or below the level of the disc space, it really does not matter if it is attached or not. The key element is recognizing that disc material is present away from the level of the disc space (caudally or cranially) so that the surgeon will be aware that he or she may have to increase his or her exposure to find and account for the additional disc material, whether it is attached to the parent disc or not. Free fragments are diagnosed on MRI scans by noting disc material cephalad or caudal to the disc space (Figure 11-8). Free fragments may migrate either cranially or caudally with no apparent preference. FIGURE 11-8

Lumbar spine: Disc disease and stenosis

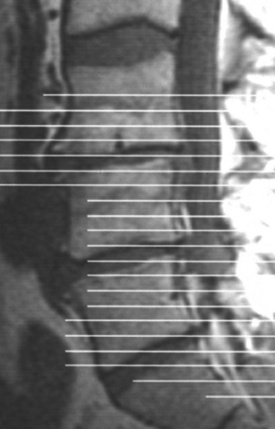

Desiccated disc. A sagittal T2-weighted image shows the L2–3 and L3–4 discs to be abnormally low in signal, indicating disc desiccation and degeneration. Compare with the normal L1–2 disc (arrow), which has high signal.

Desiccated disc. A sagittal T2-weighted image shows the L2–3 and L3–4 discs to be abnormally low in signal, indicating disc desiccation and degeneration. Compare with the normal L1–2 disc (arrow), which has high signal.

Imaging protocols

Inadequate technique—skip areas. A CT scout film with cursors placed through the disc spaces. This allows large gaps or skip areas that can result in multiple missed diagnoses, including missed free fragments of discs.

Inadequate technique—skip areas. A CT scout film with cursors placed through the disc spaces. This allows large gaps or skip areas that can result in multiple missed diagnoses, including missed free fragments of discs.

Proper MRI technique. This MRI scout with cursors placed contiguously from the body of L3 to S1 allows complete coverage of the lower lumbar spine in the axial plane.

Proper MRI technique. This MRI scout with cursors placed contiguously from the body of L3 to S1 allows complete coverage of the lower lumbar spine in the axial plane.

Disc disease

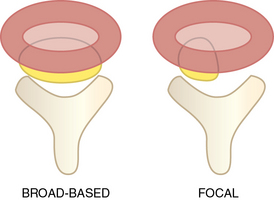

Schematic of types of disc bulges. The broad-based disc bulge (left) is typical for a bulging annulus fibrosus. A focal disc bulge (right) is more consistent with a protrusion.

Schematic of types of disc bulges. The broad-based disc bulge (left) is typical for a bulging annulus fibrosus. A focal disc bulge (right) is more consistent with a protrusion.

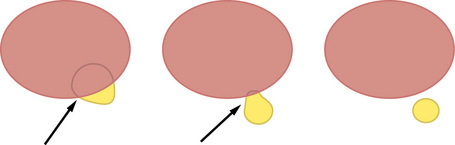

Disc protrusions. A, A focal disc protrusion with a wide neck or base (arrow). This has been termed a protrusion. B, A focal disc protrusion with a narrow neck or base (arrow). This has been termed an extrusion. C, A piece of disc that has broken off as a free fragment. This has been termed an extruded disc.

Disc protrusions. A, A focal disc protrusion with a wide neck or base (arrow). This has been termed a protrusion. B, A focal disc protrusion with a narrow neck or base (arrow). This has been termed an extrusion. C, A piece of disc that has broken off as a free fragment. This has been termed an extruded disc.

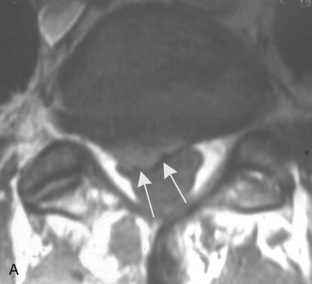

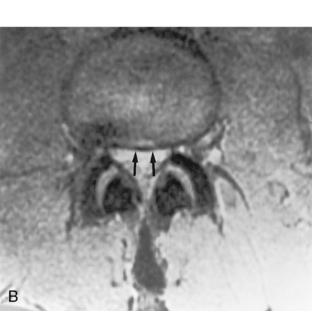

Disc protrusions. A, An axial T1-weighted image shows a focal disc protrusion (arrows). B, An axial T2-weighted image shows a broad-based disc bulge (arrows). Because these are both showing impression of the thecal sac, they could each cause symptoms.

Disc protrusions. A, An axial T1-weighted image shows a focal disc protrusion (arrows). B, An axial T2-weighted image shows a broad-based disc bulge (arrows). Because these are both showing impression of the thecal sac, they could each cause symptoms.

Annular tear. This sagittal fast spin-echo T2-weighted image shows a focus of increased signal (arrow) in the annulus, which is called an HIZ (high-intensity zone). This indicates an annular tear.

Annular tear. This sagittal fast spin-echo T2-weighted image shows a focus of increased signal (arrow) in the annulus, which is called an HIZ (high-intensity zone). This indicates an annular tear.

Free fragments

Sequestration or free fragment. This sagittal T2-weighted image shows disc material located caudal to the parent disc (arrow). This is a sequestration or free fragment. It may still be attached and technically is not a “free” fragment, but it has the same significance whether it is attached or not.

Sequestration or free fragment. This sagittal T2-weighted image shows disc material located caudal to the parent disc (arrow). This is a sequestration or free fragment. It may still be attached and technically is not a “free” fragment, but it has the same significance whether it is attached or not.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Lumbar spine: Disc disease and stenosis