CHAPTER 10 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the shoulder has been shown to have a high degree of accuracy, especially when performed with arthrography.1,2 Although most texts divide the shoulder into either cuff or labral abnormalities, it is important to know that cuff and labral pathology often coexist, causing great confusion in the clinical presentation and the physical examination. Most surgeons are aware that failure to address a labral abnormality when fixing a torn cuff can result in failed surgery and, conversely, fixing a labral abnormality and ignoring a cuff problem may not address the patient’s real problem. MRI examination can show both the cuff and the labrum to good advantage. Also, an MRI scan of the shoulder may reveal one of the entities I discuss in the last part of this chapter, such as suprascapular nerve entrapment, quadrilateral space syndrome, or Parsonage-Turner syndrome, any one of which can present clinically with findings similar to a cuff problem. The rotator cuff is composed of the tendons of four muscles that converge on the greater and lesser tuberosities of the humerus: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor (Figure 10-1). Of these, the supraspinatus tendon is the one that most commonly causes clinically significant problems and is almost exclusively the one that is addressed surgically. FIGURE 10-1 There are many variations in the imaging protocol that are all acceptable for showing normal and pathologic findings in the shoulder. The rotator cuff, that is, the supraspinatus tendon, is best seen on oblique coronal images that are aligned parallel to the supraspinatus muscle (Figure 10-2). T2-weighted sequences, or acceptable variations, are mandatory. A commonly used protocol is an oblique coronal fast spin-echo (FSE) T2-weighted sequence with fat suppression. The slice thickness should be no greater than 5 mm, with 3 mm being preferable. As with most joint imaging, a small field of view (FOV) (16 to 20 cm) is recommended. A dedicated shoulder coil or a surface coil placed anteriorly over the shoulder is necessary, although no particular type of shoulder coil appears to be clearly superior. FIGURE 10-2 The oblique sagittal sequence is one of the most useful and is performed in our protocol as a standard T1-weighted sequence without fat suppression (to identify fatty atrophy) and as a FSE T2-weighted sequence with fat suppression. This is very useful in identifying cuff tears, fluid collections about the shoulder, and muscle edema. With T2 weighting, fluid in the subacromial bursa can occasionally be seen to better advantage than on the oblique coronal images. The rotator cuff commonly suffers from what has been termed impingement syndrome. This was first described by Neer, an orthopedic surgeon, who claims that 95% of all rotator cuff tears occur from impingement syndrome. Impingement of the critical zone of the supraspinatus tendon occurs from abduction or flexion of the humerus, which allows the tendon to be impinged between the anterior acromion and the greater tuberosity. The tendon can also be impinged by the undersurface of the acromioclavicular (AC) joint if downward-pointing osteophytes or a thickened capsule is present. Other theories exist for impingement syndrome, including natural degeneration from aging and a predisposition for the critical zone to undergo degeneration as a result of decreased blood supply.3 Most investigators agree that, whatever the cause, the natural course of impingement syndrome leads to a complete, or full-thickness, tear of the rotator cuff. Treatment of impingement syndrome consists of rest, subacromial bursa steroid injections, and, if refractory to conservative care, surgery. Surgery involves removal of the anterior third of the acromion, resection of the coracoacromial ligament, and removal of any irregularities on the undersurface of the AC joint. If a tear of the supraspinatus tendon is present, it is repaired. Intrinsic degeneration (also called myxoid degeneration) is believed by many surgeons to be more significant than anatomic impingement as a source of cuff pathology.4 In examining the rotator cuff the anterior most oblique coronal images will show the critical zone of the supraspinatus tendon. A useful landmark for noting the supraspinatus tendon is the bicipital groove, which has the anterior-most fibers of the supraspinatus just lateral to the groove. This is where most cuff tears begin and can be easily overlooked if the shoulder is internally rotated, which is common (Figure 10-3).5 FIGURE 10-3 The normal supraspinatus tendon is said to be uniformly low in signal on all pulse sequences. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. In fact, it usually has some intermediate to high signal in the critical zone, which has caused much confusion in the evolution of interpreting shoulder MRI examinations. We imaged around 20 “normal” volunteers (residents and fellows) in the early days of learning how to read an MRI scan of the shoulder and found only one or two that had uniform low signal throughout the critical zone. This was very distressing because the literature at that time said any high signal in the critical zone meant it was abnormal. We know now that there are many causes for intermediate to high signal on T1-weighted images in the normal shoulder. We no longer even obtain an oblique coronal T1-weighted sequence, because it does not add any additional information to the oblique coronal FSE T2-weighted sequence. If signal in the critical zone is brighter on the T2-weighted images, it is abnormal and represents a partial tear if it is fluid bright. A partial tear can also be present if the cuff has focal thinning of the tendon (Figure 10-4). FIGURE 10-4 Myxoid or fibrillar degeneration of the supraspinatus tendon is commonly found in autopsy specimens and increases with age. The majority of asymptomatic shoulders in patients older than age 50 are believed to have some tendon degeneration in the supraspinatus tendon, which has been termed tendinopathy. This is seen as intermediate to high signal in the critical zone on T1-weighted images that does not increase with T2 weighting.6 Some tendon degeneration (tendinopathy) can be seen in asymptomatic shoulders in patients of all ages; hence, it needs to be correlated with the clinical picture. If the signal gets brighter on T2-weighted images, it must be considered pathologic—a partial tear. If intermediate signal in the cuff tendons is accompanied by fusiform or focal thickening, myxoid degeneration is present (Figure 10-5). Surgeons will debride this when it is prominent.4 FIGURE 10-5 If disruption of the supraspinatus tendon can be seen, obviously a full-thickness tear is present (Figure 10-6). In these cases fluid is invariably present in the subacromial bursa. Care should be taken to look for retraction of the supraspinatus muscle, because marked retraction will obviate some types of surgery.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulder

Anatomy

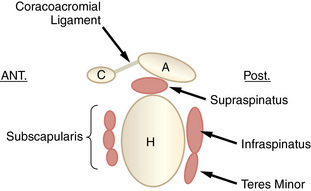

Schematic of shoulder anatomy. This drawing shows the rotator cuff muscles in a sagittal plane (anterior is on the left). A, Acromion; C, coracoid; H, humeral head.

Schematic of shoulder anatomy. This drawing shows the rotator cuff muscles in a sagittal plane (anterior is on the left). A, Acromion; C, coracoid; H, humeral head.

Imaging protocol

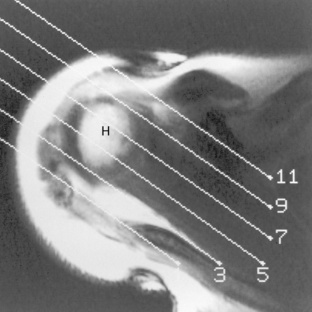

Scout view for oblique coronal images. This axial image through the supraspinatus tendon shows the cursors angled along the plane of the supraspinatus muscle (anterior on top). H, Humeral head.

Scout view for oblique coronal images. This axial image through the supraspinatus tendon shows the cursors angled along the plane of the supraspinatus muscle (anterior on top). H, Humeral head.

Rotator cuff

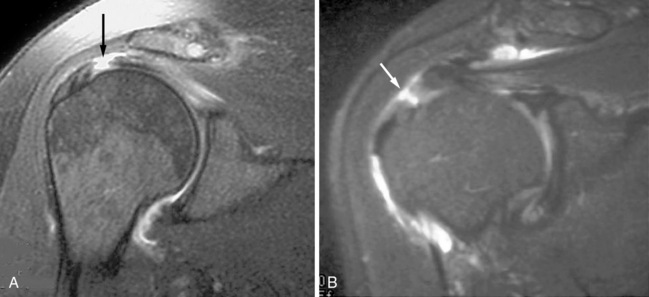

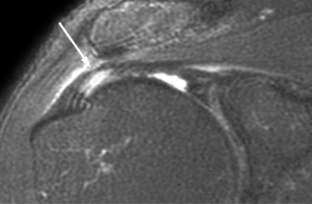

Internal rotation hiding partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon. A, An oblique coronal FSE T2-weighted image shows an apparently normal supraspinatus tendon inserting onto the greater tuberosity (arrow). B, One slice anteriorly, the bicipital groove can be identified with the anterior fibers of the supraspinatus tendon just lateral to the groove lifted off of the greater tuberosity (arrow). This is a partial tear of the rotator cuff at its anterior-most portion.

Internal rotation hiding partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon. A, An oblique coronal FSE T2-weighted image shows an apparently normal supraspinatus tendon inserting onto the greater tuberosity (arrow). B, One slice anteriorly, the bicipital groove can be identified with the anterior fibers of the supraspinatus tendon just lateral to the groove lifted off of the greater tuberosity (arrow). This is a partial tear of the rotator cuff at its anterior-most portion.

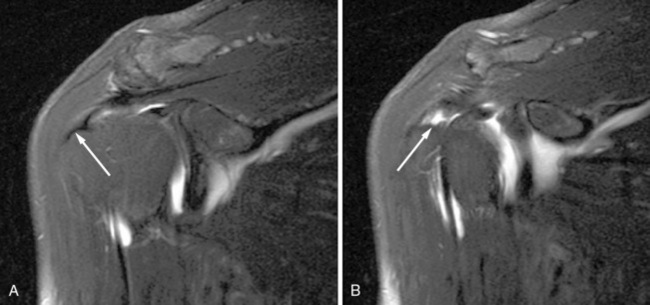

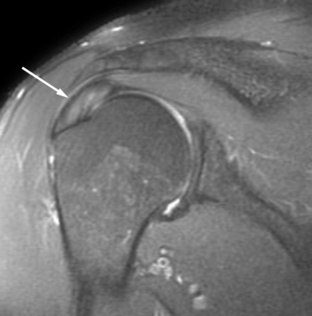

Partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon. An oblique coronal FSE T2-weighted image with fat suppression shows thinning of the supraspinatus tendon (arrow), which is a partial articular-sided cuff tear.

Partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon. An oblique coronal FSE T2-weighted image with fat suppression shows thinning of the supraspinatus tendon (arrow), which is a partial articular-sided cuff tear.

Tendinosis. An oblique coronal FSE T2-weighted image shows intermediate signal in a supraspinatus tendon (arrow) that has fusiform swelling. This is myxoid degeneration or tendinosis.

Tendinosis. An oblique coronal FSE T2-weighted image shows intermediate signal in a supraspinatus tendon (arrow) that has fusiform swelling. This is myxoid degeneration or tendinosis.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the shoulder