Malignant Lesions

INVASIVE DUCTAL CARCINOMA

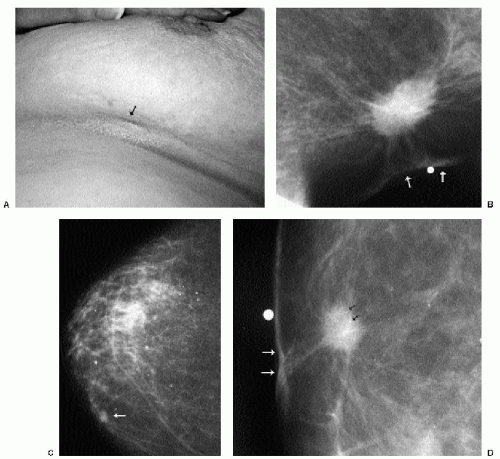

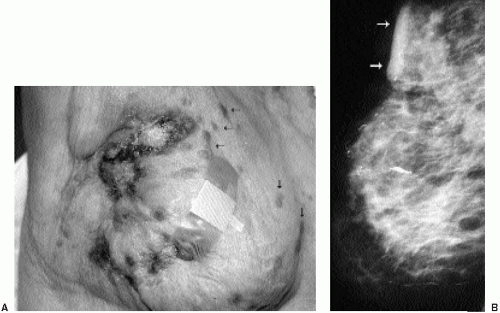

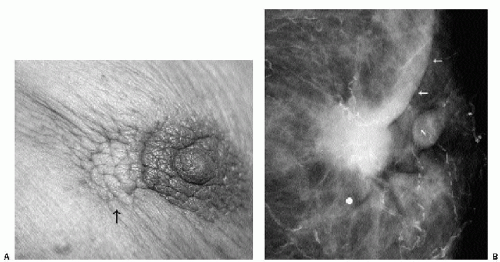

Invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), or no special type, is the most common type of breast cancer, representing 65% to 75% of mammary carcinomas (1,2). Patients may present with a hard, fixed, palpable mass that may cause skin thickening and retraction (Figure 7.1). When more advanced, breast cancer can deform the breast with a protruding, fungating (Figure 7.2), or ulcerating (Figure 7.3) mass. If the cancer develops close to the subareolar area, patients may describe progressive nipple inversion or retraction (Figure 7.4). Rarely, patients present with spontaneous nipple discharge, and less than 1% of patients present with metastatic disease to the axilla but no clinically or mammographically apparent primary lesion in the ipsilateral breast. In these patients, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may prove to be helpful in identifying the primary lesion (3).

Invasive ductal carcinomas, not otherwise specified, represent 65% to 75% of all diagnosed breast cancers.

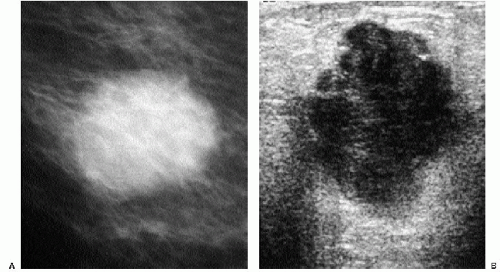

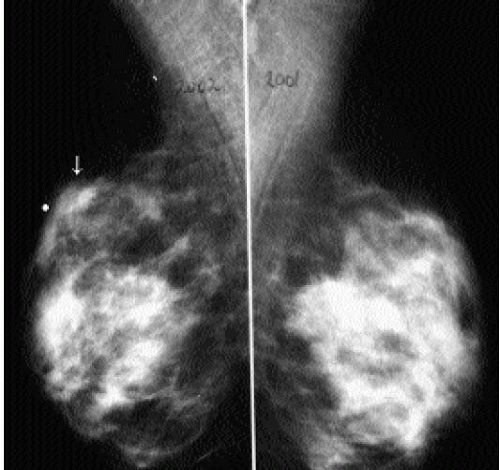

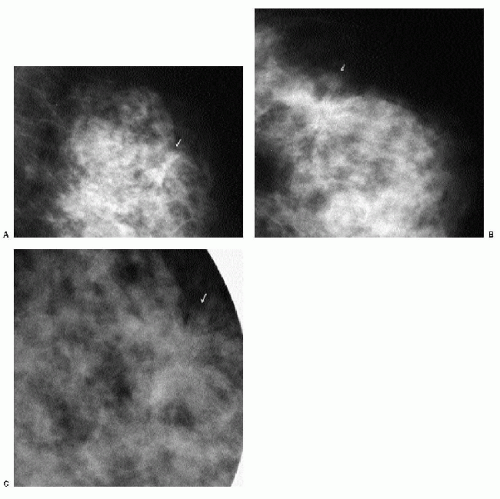

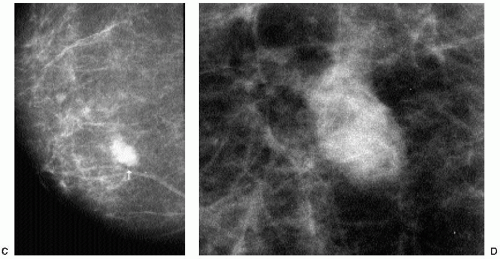

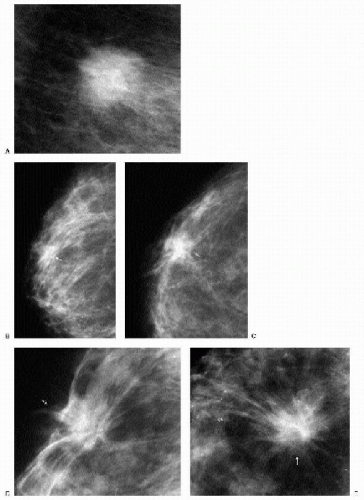

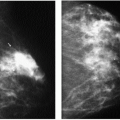

With the increasing use of screening mammography, patients with invasive ductal carcinomas are diagnosed before signs of cancer are detected or symptoms have developed. A spiculated mass (Figure 7.5) is the most common mammographic finding in asymptomatic women. The mass may cause architectural distortion and have associated malignant-type calcifications indicating an associated intraductal component. Less commonly, invasive ductal carcinoma presents as a round or oval mass with well-circumscribed to ill-defined or indistinct margins (Figure 7.6A), focal parenchymal asymmetry (Figure 7.7), distortion (Figure 7.8), or diffuse changes (Figure 7.9). The density of the lesions is variable, and these masses can be low density (Figure 7.10).

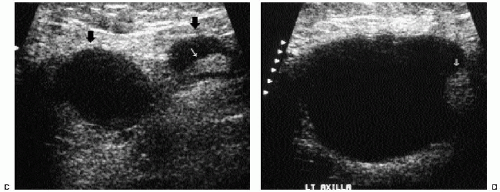

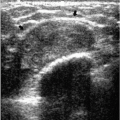

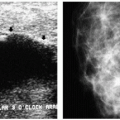

In many women, the mammographic features of a mass (e.g., spiculated with linear, casting-type calcifications) are such that an ultrasound does not add significant information. In these patients, ultrasound is done primarily to help direct the imaging-guided biopsy. In other patients, however, ultrasonography is helpful and compliments mammography in characterizing lesions. As discussed in Chapter 4, when a patient presents with a palpable mass and dense tissue is seen mammographically at the site of clinical concern, ultrasonography is critical in the characterization of the palpable abnormality (Figure 7.11). On ultrasound, an irregular, ill-defined hypoechoic mass is often imaged corresponding to the mass seen mammographically or palpated clinically. Spiculation, microlobulation, vertical orientation, angular margins, calcifications, extension of tumor into ducts pointing toward the nipple, and branching of tumor away from the nipple with variable amounts of shadowing are additional findings associated with malignancy (4). In patients with predominantly fatty tissue, and less commonly glandular tissue, the ultrasound study may be normal because the lesion is isoechoic to the surrounding tissue (Figure 7.11C, D). Many of our patients with invasive ductal carcinoma NOS presenting with a round mass (expansile margins), posterior acoustic enhancement and marked hypoechogenicity, have poorly differentiated, rapidly growing tumors (Figure 7.6B).

Figure 7.3 Moderately differentiated invasive ductal carcinoma, not otherwise specified. A 78-year-old patient with ulceration (arrow) secondary to underlying advanced breast cancer. |

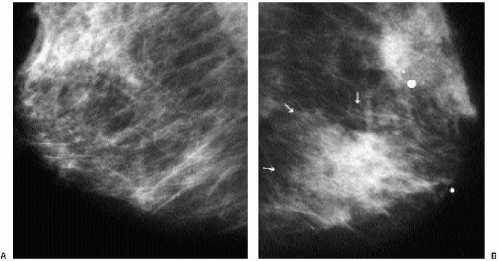

It is important to recognize that patients with breast cancer are at significantly higher risk for other lesions. Multifocal lesions are defined as multiple cancers occurring in the same quadrant (Figure 7.12), whereas multicentric cancers are those occurring in different quadrants of the involved breast. Bilateral cancers are synchronous (Figure 7.13) when diagnosed at the same time, or within 6 months of each other, and metachronous (Figure 7.14) when they occur bilaterally at different times (diagnosed more than 6 months apart). The reported frequency of multifocality varies, depending on study design and meticulousness of histologic evaluation, and may be as high as 33% to 50% (5,6).

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI is emerging as a powerful tool that, when used in conjunction with mammography and ultrasound, can help establish the presence of clinically occult multifocal and multicentric disease.

The described frequency of synchronous lesions is 0.1% to 2%, compared with 1% to 12% for metachronous lesions. The risk for subsequent breast cancer development among patients with a history of breast cancer is significant, and some of the factors to consider

in assessing this risk are listed in Box 7.1. In the general population, 0.1% of women per year are expected to develop breast cancer. In comparison, the frequency of developing a second breast cancer among patients with a history of breast cancer is 0.53% to 0.8% per year (6). Nielsen and colleagues reported on 86 women with a diagnosis of invasive ductal carcinoma, in whom, at autopsy, invasive and in situ lesions were identified in the contralateral breast in 33% and 35% of patients, respectively (7). In a separate study done by the same investigators in an age-matched population, autopsy results identified 14 patients with in situ lesions and only 1 patient with invasive cancer among 77 women with no history of breast cancer (8).

in assessing this risk are listed in Box 7.1. In the general population, 0.1% of women per year are expected to develop breast cancer. In comparison, the frequency of developing a second breast cancer among patients with a history of breast cancer is 0.53% to 0.8% per year (6). Nielsen and colleagues reported on 86 women with a diagnosis of invasive ductal carcinoma, in whom, at autopsy, invasive and in situ lesions were identified in the contralateral breast in 33% and 35% of patients, respectively (7). In a separate study done by the same investigators in an age-matched population, autopsy results identified 14 patients with in situ lesions and only 1 patient with invasive cancer among 77 women with no history of breast cancer (8).

Box 7.1: Factors to Consider in Assessing Risk for Subsequent Breast Cancer Development in Patients with Personal History of Breast Cancer

Tumor size

Degree of anaplasia

Location

Clinical stage

Family history

Multicentricity

Ductal carcinoma in situ

Premenopausal (younger patients)

Genetics: BRCA1 and BRCA2

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Histology of lesion (greater incidence with tubular or invasive lobular carcinomas)

When a patient with breast cancer develops a lesion in the contralateral breast, the second lesion may represent a second primary or a metastasis from the prior lesion (6). In considering prognosis and treatment options for the patient, it is important to distinguish between these two considerations (Figure 7.14). The features suggestive of a second primary are contrasted with the features suggestive of metastatic disease in Table 7.1.

In women with known invasive breast primary tumors, we routinely scan the ipsilateral axilla. Ultrasound evaluation in patients with suspected axillary adenopathy can be useful because it provides access to an area that may be difficult to evaluate mammographically. Ultrasonographic features of axillary lymph nodes that raise our concern include marked hypoechogenicity (in some patients, nearly anechoic) with through transmission, bulging cortex, mass effect, attenuation or obliteration of the

hyperechoic fatty hilum (Figure 7.6C, D), and increased blood flow. If a suspicious node is identified, a core biopsy or fine-needle aspiration is done at the time of the primary breast lesion biopsy. Patients identified with metastatic disease bypass sentinel lymph node biopsy and go on to have full axillary dissections at the time of the lumpectomy. When an abnormal intramammary lymph node is identified and found to be positive for metastatic disease, consider preoperative wire localization of the intramammary lymph node. These nodes are not routinely excised during axillary dissections.

hyperechoic fatty hilum (Figure 7.6C, D), and increased blood flow. If a suspicious node is identified, a core biopsy or fine-needle aspiration is done at the time of the primary breast lesion biopsy. Patients identified with metastatic disease bypass sentinel lymph node biopsy and go on to have full axillary dissections at the time of the lumpectomy. When an abnormal intramammary lymph node is identified and found to be positive for metastatic disease, consider preoperative wire localization of the intramammary lymph node. These nodes are not routinely excised during axillary dissections.

Table 7.1: Features of Second Primary Tumor Compared with Metastasis from Contralateral Breast | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Histologically, invasive ductal carcinomas, NOS, demonstrate variable growth patterns (infiltrative, expansile), cellular morphology, and no special features. Several grading systems are available based on tubule formation, nuclear morphology, and mitotic activity. Estrogen receptors are reportedly positive in 55% to 72% of lesions; however, poorly differentiated lesions are less likely to have estrogen receptors. Progesterone receptors occur in 33% to 70% of lesions, and about 15% of lesions are estrogen receptor positive and progesterone receptor negative (1,2,6).

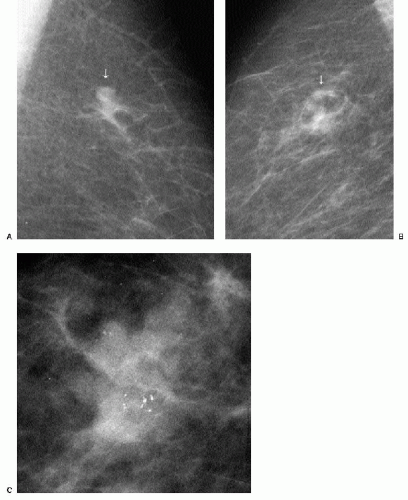

EXTENSIVE INTRADUCTAL COMPONENT

Patients with invasive ductal carcinomas and extensive areas of associated intraductal carcinoma were initially thought to have a worse prognosis and were described as having a higher incidence of local recurrence after conservative treatment. This is probably related to incomplete resection of the lesion and residual disease in the breast (9). When lesions with an extensive intraductal component (EIC) are adequately resected, prognosis is not significantly different from that of women with lesions lacking EIC (10,11). When malignant-type calcifications are seen extending for a distance away from a clinically or mammographically detected mass (Figure 7.15), it is important to alert the surgeon

and localize the area (bracketing may be needed) so that the intraductal disease is resected with the invasive component. Definitions of EIC have varied. Currently, EIC is diagnosed when ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) constitutes 25% or more of the invasive tumor or when DCIS is present within and extends beyond the invasive component (1,2,6,12).

and localize the area (bracketing may be needed) so that the intraductal disease is resected with the invasive component. Definitions of EIC have varied. Currently, EIC is diagnosed when ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) constitutes 25% or more of the invasive tumor or when DCIS is present within and extends beyond the invasive component (1,2,6,12).

Figure 7.15 Invasive ductal carcinoma, not otherwise specified, with associated high-nuclear-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (e.g., extensive intraductal component). A 55-year-old patient. When a mass is seen with associated pleomorphic and linear calcifications, an invasive ductal carcinoma (the mass) with an associated intraductal component (the calcifications) is the likely diagnosis. If extending away from the mass, it is important that the extent of the calcifications be determined with appropriate magnification views and that this be communicated to the surgeon and pathologist. Localization of the calcifications may be indicated for adequate excision.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|