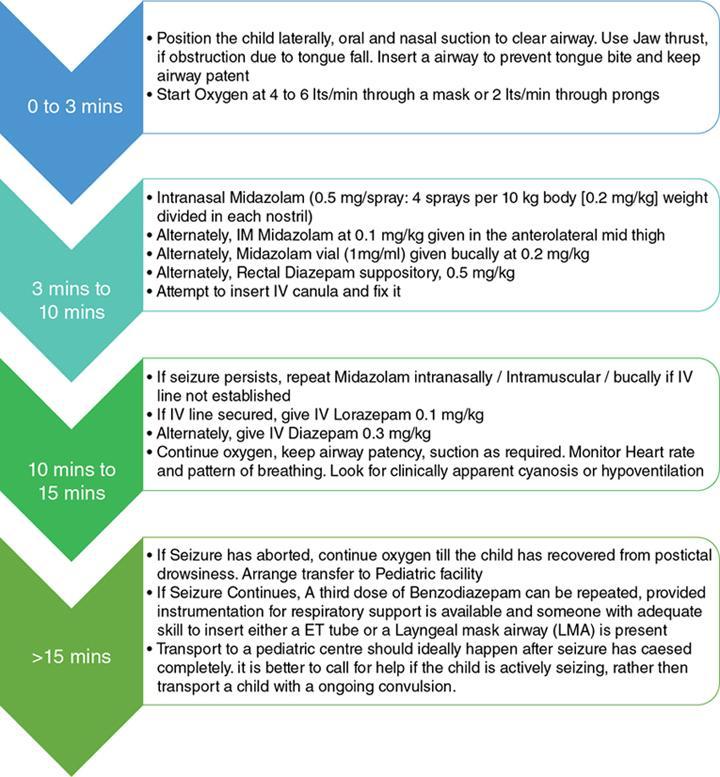

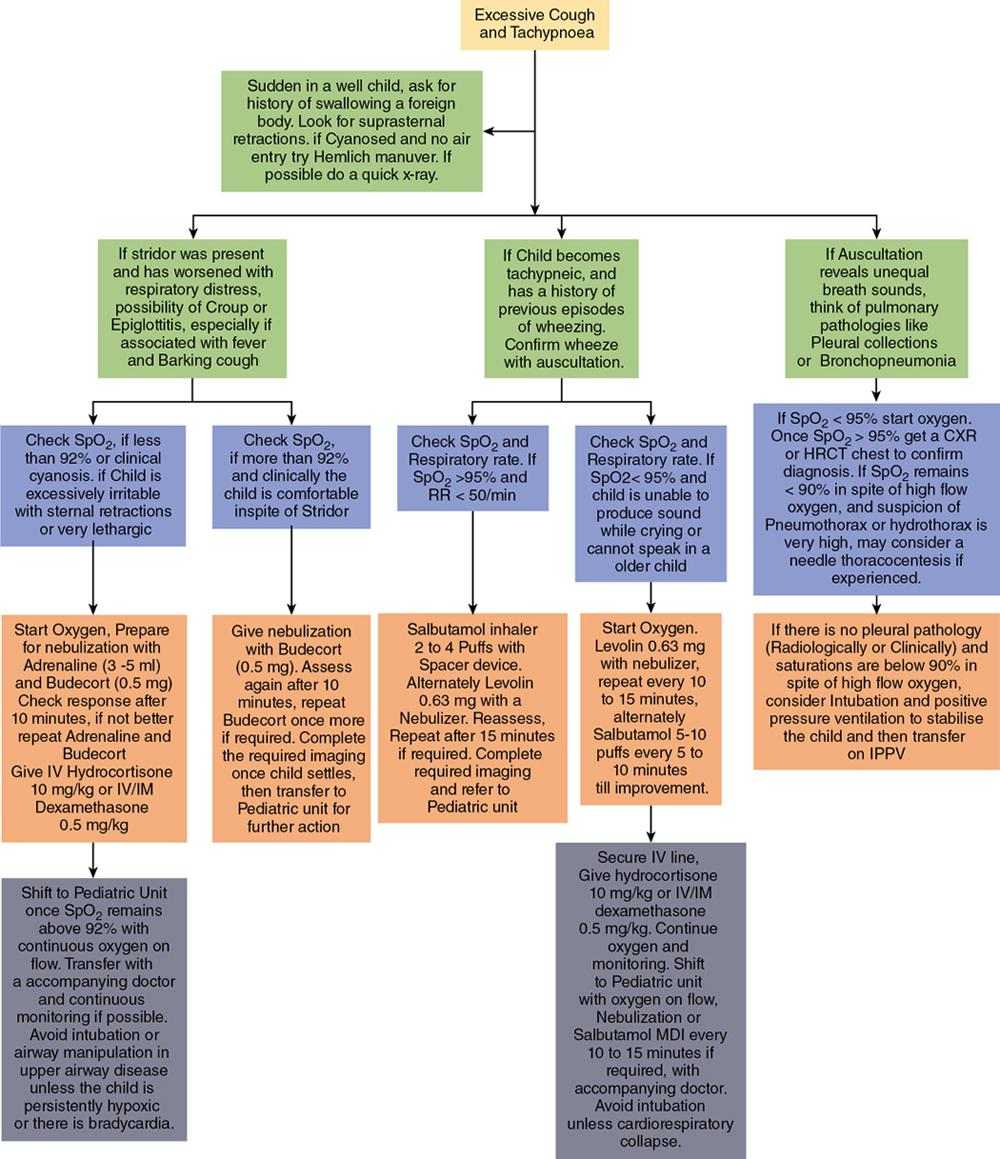

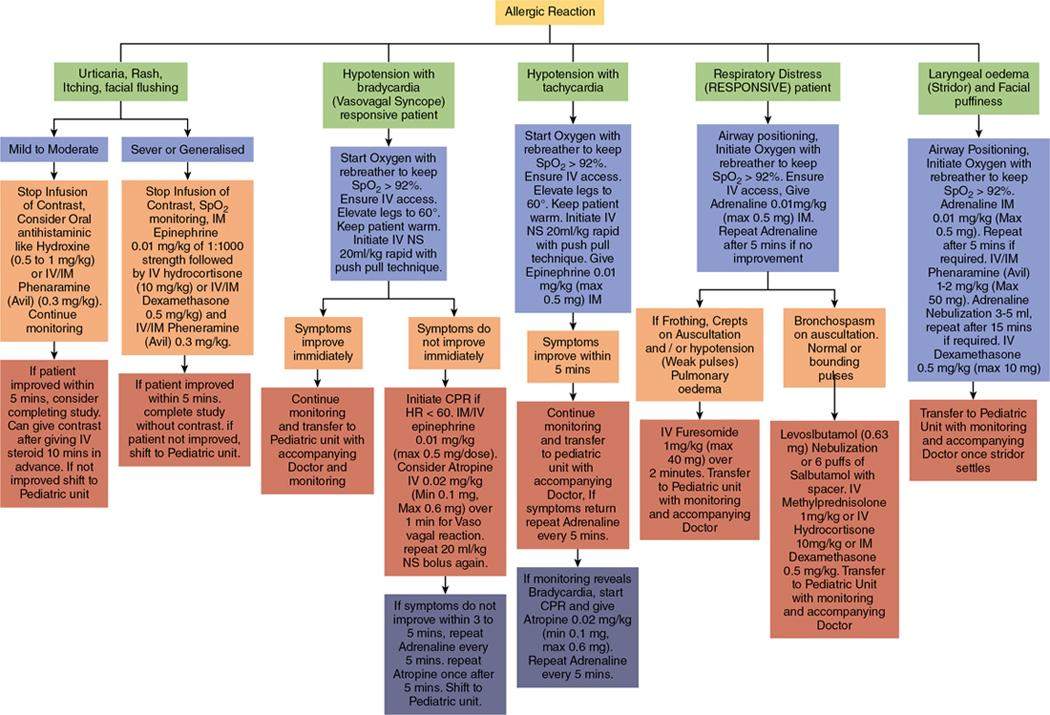

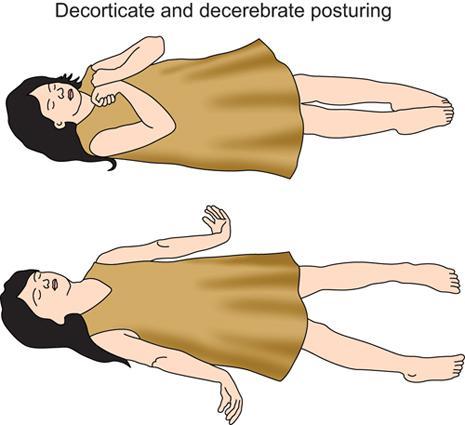

Hiren N. Doshi, Bhargavi Gohil Raval The radiology department sees children for various imaging needs on a regular basis and the radiologist should be prepared to deal with paediatric emergencies as and when they occur. Help may or may not be easily available depending on the circumstances, so the radiologist should be prepared to at least stabilize the child and transport him to the nearest paediatric centre. Management of paediatric emergencies consists of preparedness, recognition, assessment and intervention. The purpose of this chapter is to simplify all the four aspects for radiologists, who may encounter an emergency in their routine practice. These guidelines are not exhaustive and are simplified in a manner that all medical personnel can follow them, even though they are not used to dealing with children. Timely management of emergencies decreases both morbidity and mortality, thus improving outcomes. Educating self in the basics of emergency management avoids panic and medicolegal hassles. Children are more prone to seizures and most of the seizures are self-limiting. Febrile seizures are the most common type of seizure in the age group 1 year to 6 years. Other than that, metabolic seizures, infections, trauma and epilepsy are other etiological factors. Tonic clonic or only tonic seizures are the commonest ones one will encounter in practice. If the seizure lasts more than 5 min, it is presumed to be a status epilepticus, and there are high chances the child may require respiratory support. Earlier the benzodiazepine given, earlier the seizure subsides and lesser the chance of recurrence or continuing to status epilepticus. The choice of benzodiazepine and the choice of route is not the major determinant of efficacy. Rather, the most important determinant of benzodiazepine efficacy in stopping seizures is time to administration. Tip: Children rarely allow masks to be put on the face when they are irritable or crying. Removing the mask from the delivery device, either of nebulization chamber or O2 delivery system and using the ‘blow by’ method is particularly useful. Sometimes, children may get an allergic reaction to the contrast being used in radiological procedures, or because of insect bites or ingestion of unknown substances. Allergic reactions vary from mild skin rashes to sudden cardiovascular collapse and severe wheezing. Nonionic, modern iodinated, gadolinium-based and ultrasound microbubble contrast materials generally are quite safe, acute physiological and allergic-like reactions are possible. Urticaria/angioedema: Formation of wheals with surrounding erythema happens when mediators are released in the epidermal layer of the skin; these are intensely pruritic. Angioedema develops when the deeper layers of the skin and subcutaneous layers are involved. This manifests as facial, periorbital, digital and limb oedema which is more painful rather than pruritic. Allergic rhinitis: Intense sneezing and rhinoconjuctivitis result when the mediators are released in the upper respiratory tract. The conjunctivitis is intensely itchy. Allergic asthma: Bronchoconstriction, mucus production and inflammation of the airways result when the mediator release happens in the lower respiratory tract and result in chest tightness, shortness of breath and wheezing. Anaphylaxis: Sudden shock (Hypotension), severe bronchoconstriction, GI symptoms like cramping, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, throat swelling and asphyxiation in variable combinations can develop suddenly when there is a mediator storm due to a type 1 allergic reaction. This is a true medical emergency brought on by sudden vasodilatation and increased vasopermeability. Emergent management is required to avoid fatality. Allergic reactions, especially anaphylaxis, can occur unexpectedly, and every medical unit should be well prepared to deal with such an emergency. Immediate or acute-phase reactions occur within seconds to minutes after allergen exposure. Assessment should be quick, with a history of allergic tendencies and previous anaphylactic reactions asked for. Pulse should be checked for volume and rate. Microcirculation should be checked for delayed capillary refill time (CRT). Respiratory pattern, rate, intercostal, subcostal and substernal retractions should be looked for. Audible wheeze or stridor should be assessed along with increase in respiratory secretions. A general skin exam should be done to look for skin rash, flushing, pallor, oedema in the limbs, neck, etc. If time permits or if an assistant is available, a pulse oximeter should be attached and blood pressure should be documented. Attempt to put IV line should be made early, because IV access postworsening shock and limb oedema becomes exceedingly difficult. ‘Adverse reactions to intravenous administration of a nonionic contrast material are rare in children and increase in frequency with advancing age. The great majority of reactions in children are mild. To withhold contrast in children with the fear of allergic reactions or nephropathy often leads to missed diagnosis due to suboptimal study’. Capillary refill time (CRT) (Fig. 1.18.2). Intervention (Chart 1.18.3) Paediatric trauma would generally happen outside and the patient brought to the radiologist for imaging after stabilization. Rarely, you would encounter a trauma patient who comes directly for imaging. Also, patient transfers involve moving the patient from one gurney to other and these movements can suddenly cause internal or external bleeding causing shock or more serious consequences. In general, be on a look out for herniation in a head injury patient (like pupillary changes, abnormal breathing, change in sensorium, etc.), massive bleeding causing shock, which can also include hidden bleeds like in the abdominal cavity, thighs or chest. Lung punctures causing pneumothorax or haemothorax, etc. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to delve into the specifics of each separately, but a few guidelines touching on many of the above problems and how to manage primary care to stabilize the patient is what is important for radiologists. Head Trauma: If a child exhibits signs of decerebration or decortication (Fig. 1.18.3) when in the department, check pupillary size and reaction, look for inequality, miosis or mydriasis and nonreactivity to light. Secure the airway, check for vitals, and secure an IV access and push 10 mL/kg of mannitol or 5–6 mL/kg of 3% hypertonic saline rapidly. Airway protection may require placement of an airway or a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) or endotracheal tube. Elevate the head end of the bed to 30° and keep head in midline. Keep suction ready as risk of aspiration is high, but do not unnecessarily use suction, because it may raise the ICP. If possible, premedicate with ketamine 0.5 mg/kg, atropine IV 0.02 mg/kg (Min 0.1 mg, Max 0.6 mg) and lignocaine 2% spray orally or IV lignocaine 1 mg/kg 2–3 min before airway manipulation. Avoid flexing the neck during airway manipulation because of the risk of C1–C2 injury, use Jaw thrust instead. Also stabilize the neck with a cervical collar if not applied before. If an LMA or ET is inserted, transient hyperventilation with increased rate and increased tidal volume to obtain low PCo2 may help in reversing the ongoing herniation (Fig. 1.18.3). If the child has stable vitals, and the posturing decreases after initial management, a CT brain and cervical spine can be quickly obtained before transferring the child to the paediatric unit. If respiration is abnormal or there is bradycardia, it is best to defer the procedure till the child is stabilized. Control of haemorrhage: Compression at the bleeding site, or if that is not possible, then compression at the proximal arterial point decreases bleeding. Use of sterile gauzes, pads and bandages to achieve control of bleeding should be used. A tourniquet should be applied proximally to the bleeding site if possible, with due precautions and periodic assessment of distal part to avoid gangrene. Massive haemothorax may cause unilateral decreased breath sounds and dullness to percussion. Bleeding from a splenic or liver injury will present as abdominal distension and tenderness to palpation. Open abdominal or thoracic wounds will have visible external and internal bleeding. External bleeding is to be managed with compression, bandages and gauze pads to minimize bleeding. Haemothorax may require a rapid chest tube insertion with a large bore tube at least 10 fr. or above to prevent hypoxaemia. Assessment of shock is described below. A rapid CT of thorax, abdomen and pelvis or a quick ultrasound scan of the same will confirm internal injuries. Many times, chest injuries present with pneumothorax or both haemothorax and pneumothorax, and placing two chest tubes may be required, one in the anterior mediastinum and other in the posterior mediastinum. Identification of Shock: Increase in heart rate with cool extremities is shock. Other features are decrease in pulse pressure to less than 20 mm Hg, delayed capillary refill, mottled skin and decreased level of consciousness. Management of Shock: Secure IV access, if not possible, intraosseous insertion in the shin of Tibia is a reasonable alternative. Push 20 mL/kg of NS or RL as a bolus. Repeat every 5 min till 60 mL/kg is given. Keep monitoring vitals and body temperature to determine volume and rate of infusion. Cardiac tamponade may manifest as Beck triad (increased venous pressure [distended neck veins], muffled heart sounds and hypotension). Rapid screening with ultrasound and guided drainage of the tamponade till the patient is shifted to the OT may be lifesaving. The order of priority in the initial assessment and treatment in Advance trauma life support (ATLS) is called the “primary survey” and includes:

1.18: Management of neonate, infant and paediatric population in radiology

Paediatric emergencies and their management in the radiology department

Paediatric cabinet/crash cart essentials

Medications

Seizure

Allergic reactions

Recognition and assessment

Trauma in children

Management of bleeding from extremities and scalp

Management of bleeding in the chest or abdominal cavity

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree