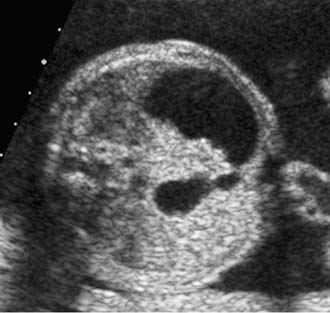

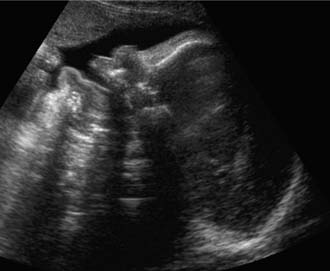

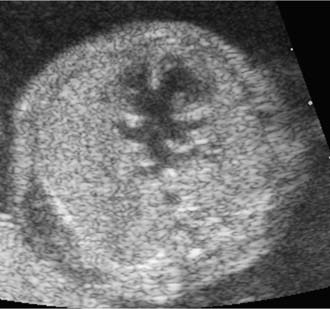

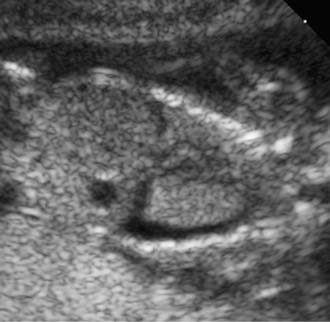

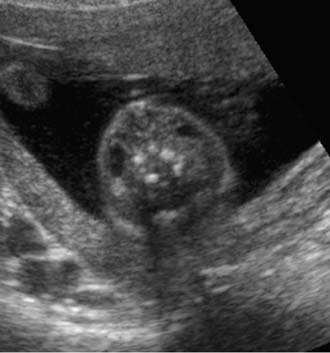

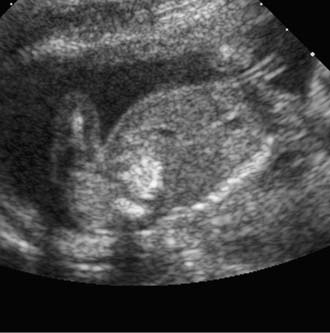

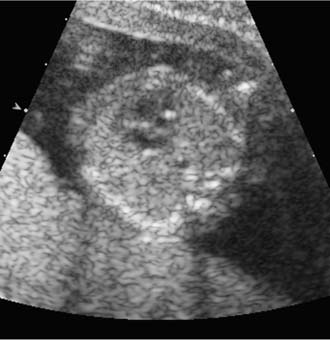

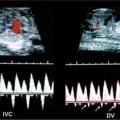

18 Maternal Serum Screening Test Positive for Down Syndrome Down syndrome is the most common karyotypic abnormality among liveborns.1 Over the past few decades, much research has concentrated on screening for fetal Down syndrome and the prenatal diagnosis of this condition. The primary factor associated with fetal Down syndrome is maternal age. The rate of fetal Down syndrome increases with increasing maternal age. Because most women who are delivering babies are younger, the majority of fetuses with Down syndrome occur in younger mothers. Therefore, using maternal age alone would be an inefficient approach for prenatal Down syndrome screening. Given the desire of many pregnant women for the knowledge of whether their fetus has Down syndrome, a relatively safe and more effective screening technique is necessary. Screening tests give us a risk estimate for fetal Down syndrome and do not diagnose a fetus as having Down syndrome. Invasive testing, such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling, is currently the only method for definitively determining the fetal karyotype. As ineffective as maternal age is as a screen for fetal Down syndrome, universal invasive testing for fetal Down syndrome also has its drawbacks. The rate of loss of normal fetuses would be excessive. A more effective screening strategy has become commonplace; namely, using maternal serum analytes to determine the risk for fetal Down syndrome. Because many varied screening strategies will be discussed, it is important to remember that there is not one best screening model.2 Further, a particular screening test may fit the needs of a patient when she is young, but it might not be optimal for her and her family as she ages.3 Women who have positive serum screening for the prenatal detection of Down syndrome frequently have a difficult time discerning the significance of the test results. For the patient faced with having some quantified risk for Down syndrome, health care providers must provide a context in which to help the patient understand the degree of risk. The majority of those with positive serum screens for Down syndrome have perfectly normal fetuses that do not have Down syndrome. Much of our mandate for these patients is to educate them about what a positive serum screen means and to provide reasonable options for the patient and her partner according to their own concerns and values. The maternal serum–α-fetoprotein test (MSAFP) was initially used as a screen for neural tube defects. Subsequently, a low MSAFP was shown to be associated with fetal Down syndrome, although the use of MSAFP and maternal age as a screening test for fetal Down syndrome was associated with a poor detection rate of ~20%.4 Within a few years, an elevated maternal serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and a low maternal serum unconju-gated estriol (uE3) were also found to be associated with Down syndrome. The use of maternal age and these three maternal serum analytes, MSAFP, hCG, and uE3, also known as the triple screen test, has been found to be effective as a screen for fetal Down syndrome. Sensitivities for the detection of fetal Down syndrome have been reported to be 50–90%, with false-positive rates of 3–6%.4–6 Generally accepted as having a sensitivity of ~75% with a false-positive rate of 5%, the triple screen test has been commonly used as a screening tool for gravidas in the second trimester for over a decade. Most recently, the inclusion of inhibin-A to the triple screen analytes has shown improved efficacy in screening for Down syndrome. The sensitivity for the detection of Down syndrome using MSAFP, hCG, uE3, and inhibin-A is ~80%, with a 5% false-positive rate and a positive predictive value of 1 in 51.7 Given these encouraging results, the quadruple test has been increasingly used over the past few years as an initial screen for fetal Down syndrome in the second trimester. As the serum screen was being developed into the currently used triple or quadruple serum analyte screens, great progress was made in the world of ultra-sound with respect to the identification of factors associated with Down syndrome. Many structural defects have been shown to be associated with Down syndrome.8These include congenital heart defects, duodenal atresia (Fig. 18–1), cerebral ventriculomegaly (Fig. 18–2), and macroglossia (Fig. 18–3). The risk of Down syndrome is generally high enough for fetuses with congenital heart defects, such as tetralogy of Fallot and atrioventricular septal defects (Fig. 18–4), duodenal atresia, and cerebral ventriculomegaly, to warrant at least a consideration of karyotyping. Abnormal fluid collections in the fetus are similarly associated with Down syndrome. Fetuses in the second trimester with Down syndrome may show signs of generalized hydrops (Fig. 18–5), or even have more localized fluid collections, such as pleural effusions (Fig. 18–6) or small nuchal cystic hygromas (Fig. 18–7). Figure 18–1 Transverse view of the fetal abdomen showing an enlarged, fluid-filled stomach and proximal duodenum secondary to duodenal atresia in a second-trimester fetus with Down syndrome. Figure 18–2 Transverse view of the fetal cranium of a second-trimester fetus with Down syndrome showing enlarged lateral ventricles consistent with ventriculomegaly. Benacerraf et al first reported the association of a thickened nuchal skin fold (Fig. 18–8) in the second trimester with Down syndrome in 1985.9 Multiple authors have subsequently confirmed this association. Benacerraf et al were able to show that 40% of fetuses with Down syndrome had an abnormally thickened nuchal fold measurement of greater than 6 mm as did 0.1% of normal fetuses. There was a positive predictive value of 69% for those with a thickened nuchal skin fold in their high-risk population.10 The thickened nuchal fold remains the most consistent sonographic sign associated with an increased risk for fetal Down syndrome. Figure 18–3 Midsagittal view of a third-trimester fetus with Down syndrome demonstrating macroglossia. Figure 18–4 Transverse view of the fetal chest at the level of the four-chamber view. There are large ventricular and atrial septal defects in this second-trimester fetus with an atrioventricular septal defect and Down syndrome. Figure 18–5 Midsagittal view of a second-trimester fetus with Down syndrome, demonstrating diffuse skin thickening and ascites consistent with hydrops fetalis. Figure 18–6 Coronal view of the second-trimester chest of a fetus with Down syndrome, demonstrating bilateral pleural effusions, left greater than right. Beyond structural defects and the thickened nuchal fold in the second-trimester fetus, many other sonographic signs have been reported that are associated with fetal Down syndrome.11,2 Some of the most studied sonographic signs include hyperechoic bowel (Fig. 18–9), short femur, short humerus, renal pyelectasis (Fig. 18–10), echogenic intracardiac foci (Fig. 18–11), and choroid plexus cysts.13 As isolated findings, a recent meta-analysis gave the following likelihood ratios (95% confidence intervals) for the above-noted sonographic signs for fetal Down syndrome in the second trimester: thickened nuchal fold—17 (8 to 38), hyperechoic bowel—6.1 (3.0 to 12.6), short femur—2.7 (1.2 to 6.0), short humerus—7.5 (4.7 to 12), renal pyelectasis—1.9 (0.7 to 5.1), echogenic intracardiac focus—2.8 (1.5 to 5.5), and choroid plexus cyst—1.0 (0.12 to 9.4).13 This meta-analysis confirms many prior studies that have documented an increased risk of Down syndrome among those fetuses with these isolated findings, except for choroid plexus cysts, which were not associated with Down syndrome. Further study is required to understand better how these sonographic signs should be used clinically. For example, fetal biometry, and even the prevalence of echogenic intracardiac foci, vary with maternal race.12 Figure 18–7 Transverse view of the fetal neck of a second-trimester fetus with Down syndrome, demonstrating small, bilateral cystic hygromas. Figure 18–8 Transverse view of the fetal cranium, demonstrating a thickened nuchal fold in a second-trimester fetus with Down syndrome. The measurement is appropriately indicated by the calipers from the outer edge of the cranium to the outer edge of the skin fold. Figure 18–9 Oblique/sagittal view of the fetal abdomen demonstrating hyperechoic bowel in a second-trimester fetus with Down syndrome. The bowel is of similar echogenicity as that of surrounding bone. Figure 18–10 Transverse view of the fetal abdomen in a second-trimester fetus with Down syndrome, demonstrating bilateral renal pyelectasis. Figure 18–11

Second-Trimester Maternal Serum Screening Test

Ultrasound Evaluation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree