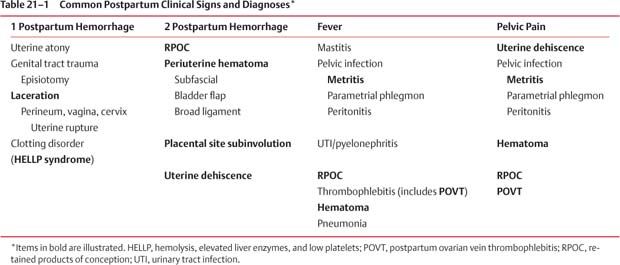

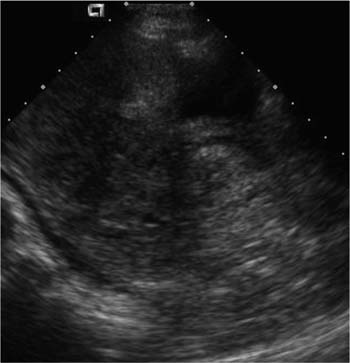

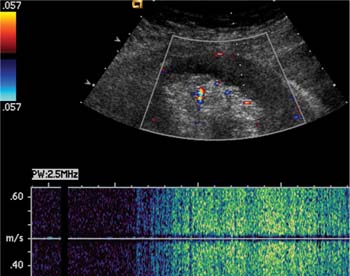

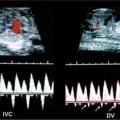

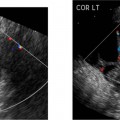

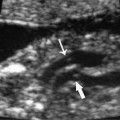

21 Postpartum Complications The sonographic diagnosis of maternal complications arising in the postpartum period, a time encompassing the puerperium and extending until roughly 6 to 8 weeks thereafter, is the focus of this chapter. The postpartum period is a time of readjustment following the tremendous physiological upheaval of pregnancy.1 Obstetrics Key organ systems (namely, genitourinary and circulatory) that have been affected by the hormonal and vascular changes which accompany pregnancy are all undergoing changes in size, function, and vascularity. Clinical problems that arise may be due to residua of pregnancy or a wholly unrelated, coincidental pathological process. Although radiological imaging can undoubtedly assist in uncovering the problem, it is important to be aware of the normal appearance of key organ systems to avoid misdiagnosis. This chapter focuses on the role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of postpartum clinical problems. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are both useful complementary modalities, but their use should be reserved for specific problem solving (for instance, cases of suspected parametrial infection or postpartum ovarian vein thrombophlebitis) following initial investigation with ultrasound. Given that the average radiation dose to the ovaries is 2 to 3 rem with pelvic CT, MRI may be the preferred second-line imaging modality.2 This chapter is organized into clinical symptoms and diagnoses, the normal appearance of the postpartum pelvis, and selected pathological diagnoses: retained products of conception (RPOC), postcesarean section (C-section) hematomas, postpartum ovarian vein thrombophlebitis (POVT), and endometritis. Common yet nonspecific clinical symptoms and signs that may prompt an exam include blood loss (either occult or overt), pelvic pain, and fever, potential harbingers of the dreaded “lethal triad” of maternal peripartum morbidity: namely, obstetric hemorrhage, preeclampsia, and puerperal infection.3 Of these, hemorrhage is the most common problem, affecting 1 to 2% of all deliveries. It is usually divided into primary hemorrhage (beginning with the third stage of labor and extending to the first 24 hours) and secondary hemorrhage (beyond 24 hours and extending up to 6 weeks, with peak at between 5 and 15 days post-partum).4 Major diagnostic possibilities are shown in Table 21–1. Although overt blood loss is usually due to genital tract trauma (Fig. 21–1) and will generally prompt a quick investigation, occult bleeding may go unrecognized due to the 30 to 60% blood volume expansion during pregnancy, making hematocrit measurements less reliable in the estimation of blood loss.5 Occult blood loss, such as hemoperitoneum and periuterine and hepatic subcapsular hematoma (Fig. 21–2), is readily demonstrated with ultra-sound and may indicate unrecognized hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP syndrome). Pelvic pain or mass can be a manifestation of any of the hematomas listed above, as well as unrecognized uterine rupture, pelvic infection, or ovarian vein thrombophlebitis. Postpartum fever is generally defined as any temperature > 38°C (100.4°F) on any 2 days of the first 10 days after delivery, exclusive of the first day (due to the frequency of self-limiting mastitis in the first 24 hours).3 Clinical factors affecting the risk of postpartum infection include prolonged labor, preterm rupture of membranes, and C-section delivery. For example, postpartum endometritis has a 2 to 3% incidence following vaginal delivery, whereas the incidence following C-section is 6 to 10%; these incidences increase significantly in the face of preterm rupture of membranes or chorioamnionitis to 13% and 85% for vaginal delivery and C-section, respectively.4,6 As examination of Table 21–1 shows, clinical manifestations in and of themselves are quite nonspecific and may have overlapping etiologies. Although a consideration of time of onset of symptoms can be helpful, pelvic ultrasound can often yield specific-enough findings to rule in or out many of these conditions. Figure 21–1 Cervical laceration. Forty-year-old woman with bleeding immediately following therapeutic abortion at 20 weeks. Sagittal transabdominal sonogram shows echogenic mass expanding the cervical area and extending into the vaginal fornices; the patient was treated with emergency uterine artery embolization. A brief review of sonographic technique follows. Even without a full bladder, transabdominal imaging gives the best overall view of the uterus and ovaries because the fundus is often beyond the reach of the transvaginal scan, especially in the first 4 weeks postpartum. Examination of the anterior wall C-section scar for subfascial collections can only be accomplished transabdominally (and may require higher frequency linear transducers for optimal visualization); frequently the lower uterine segment C-section site can be adequately seen as well. The transvaginal approach is recommended in the latter half of the puerperium (weeks 4 to 8) for a detailed view of the endometrial cavity if retained products are suspected, especially to investigate blood flow. Transperineal imaging is an adequate alternative method to image the lower uterine segment/cervix and cul-de-sac in patients with an open wound in whom the transvaginal approach is not feasible. Proper Doppler technique to evaluate uterine blood flow includes attention to gain settings and interrogating frequency, as well as use of pulsed Doppler to elucidate the flow profiles of any color Doppler findings. Regarding the latter point, color “flash” artifacts should not be overinterpreted as evidence for true flow because hyperechoic foci due to air or calcifications, commonly seen in the postpartum uterus, can give rise to spurious color signals (Fig. 21–3). Figure 21–2 Postpartum hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP syndrome) with hepatic subcapsular hematoma. Patient 8 days postpartum with fever, decreasing hematocrit level, and right upper quadrant pain. Transverse transabdominal sono-gram shows complex subcapsular fluid collection, a small amount of ascites, and gallbladder sludge. (From Di Salvo DN. Sonographic imaging of maternal complications of pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med 2003;22:72. Reprinted by permission.) Figure 21–3 False-positive color Doppler signals in devitalized placenta accreta. Patient 3 weeks following bilateral uterine artery embolization, currently asymptomatic. Sagittal transabdominal ultrasound with color and pulsed Doppler shows spurious color flow signals and noise due to flash color artifacts. The uterus does not return to its pregravid size and position until ~8 weeks after delivery, with the greatest decrease occurring during the first month.7,2 The process of uterine involution involves both myometrial and endometrial changes. Hyalinization of pregnancy-hypertrophied myometrial vessels leads to ischemic atrophy of the fundus. The vascular basis for this process has been validated in Doppler studies of the uterine artery in the puerperium that show increase in resistive indices beginning by the second postpartum day and continuing for the next 6 weeks; these studies also suggest the vascular basis for subinvolution of the uterus in cases of secondary postpartum hemorrhage (see next section).8–12 Concurrent with myometrial involution, sloughing of the decidua superficialis layer of the endometrium occurs, leading to vaginal discharge, termed lochia rubra in the first 3 to 4 days, changing to lochia alba thereafter. The regeneration of the endometrium from the remaining basalis layer is generally complete by the third week postpartum, except at the placental implantation site, which may take up to 8 weeks to fully heal. Histological studies have shown that inflammatory changes similar to those seen in endometritis are part of the normal reparative process.1 One longitudinal sonographic study of the uterus in 42 women following un-complicated vaginal delivery from day 1 to day 56 showed that the uterine fundus and corpus rotates 100 to 180 degrees relative to the lower uterine segment as follows: Beginning slightly retroverted on days 1 to 3, it becomes co-linear on day 7, and finally slightly anteverted from week 2 on (Fig. 21–4A,B). The greatest size decrease, measured as maximal anteroposterior (AP) uterine thickness, occurred in the first 2 weeks, with a more gradual return to prepregnant dimensions between weeks 4 to 8. Findings in the endometrial cavity in this study were somewhat more complex: On day 1 the upper endometrial cavity was most often empty (93%), whereas debris and fluid were present in the cervical area in 79% (Fig. 21–4C). An increase in upper cavity size and contents was seen between days 7 and 14 in 90% of patients, likely reflecting necrotic deciduas superficialis, which was expelled by the time of follow-up at 4 weeks.13 A later study included 40 postpartum women making an uncomplicated recovery following vaginal delivery, who were serially imaged at 1, 2, and 3 weeks. An echogenic intracavitary mass was seen in 51, 21, and 6% of women at the aforementioned times, but there was no correlation with amount or duration of bleeding14 (Fig. 21–4D). CT and MRI studies have confirmed the frequent presence of fluid and blood in the postpartum uterus.2,4,6 A small amount of air in the endometrial cavity, manifest as echogenic foci with ring-down artifacts, is not uncommon in the first several days after either vaginal delivery or C-section: it was present in 21% of healthy postpartum women and may persist for up to 3 weeks4,2 (Fig. 21–4E). Following a C-section, there are postsurgical changes in both the subfascial tissues as well as in the anterior lower uterine segment of the uterus. Subfascial and pelvic fluid collections at least 20 mL in volume were seen in 48% of 145 women following C-section: 58/145 in the abdominal wall and 11/145 in the deep pelvis.16 Significantly, there was no correlation of febrile morbidity between women with or without these collections. The C-section site sonographically appears heterogeneous, with bright echogenic foci (sutures and/or air) intermixed with hypoechoic areas (blood) in the first several days2,16,17 (Fig. 21–5A,B). Later, the site may be manifest as a thin discontinuity of the anterior lower uterine segment, best seen transvaginally when a tiny sliver of fluid may track within the myometrial defect (Fig. 21–5C). Postpartum physiological dilatation of the right ovarian vein may be observed by examining the region of the inferior vena cava (IVC) at the level of the renal hilus (Fig. 21–5D,E). Due to the expanded volume of blood that accompanies pregnancy, dilatation of ovarian veins without thrombosis may persist for several days following delivery, as MRI techniques have confirmed. Confirmation of patency can be made through use of Doppler techniques or time of flight MRI imaging.17 Retained products of conception represent a failure of the uterus to expel part or all of the placenta following delivery. Underlying predisposing factors include adhesions, succenturiate lobe, congenital uterine anomaly, uterine atony, and uterine scarring with placenta accreta. The clinical diagnosis of RPOC, based upon postpartum bleeding in the presence of fever, pain, and an open os, is unreliable; in one study, serology for elevated HCG had low sensitivity for this diagnosis, being <30 mIU/ml in 43% of 26 patients with RPOC.18 The diagnosis of RPOC and its distinction from intrauterine hematoma is not trivial because dilation and curettage (D&C) the standard treatment for RPOC, carries an overall complication rate of 7.3%, with such risks as cervical laceration, perforation, and synechiae.19 Although placental tissue is readily recognizable with sonography during pregnancy, the appearance of residual placental tissue postpartum is complicated by the presence of coexisting blood products and necrotic decidua, which in themselves can range from echogenic to hypoechoic. Additionally, the endometrial cavity may be difficult to delineate due to the sloughing and regenerative process described earlier (see normal postpartum pelvis); on occasion, the inner myometrial layer itself may be hyperechoic, further obscuring the location of the endometrial stripe.20 Ultrasound can readily exclude retained products when the endometrial cavity is thin (< 2 mm), or contains a small amount of fluid.21 What constitutes an abnormal thickness is quite variable, with cutoff values ranging between 5 and 15 mm: Part of the confusion in the literature stems from variability of patient populations (postpartum vs postabortion) and the end points used (tissue sampling vs clinical outcome).20 Although an echogenic intracavitary mass was present in 9/11 patients subsequently shown to have retained products, reliance on this feature alone resulted in a 34% false-positive rate in a later study because hematoma and necrotic decidua may also be echogenic.22 The presence of calcifications within the intrauterine mass would favor retained products given that 50% of placentas have some sonographically visible calcifications after 33 weeks23; however, the sonographic distinction between small calcifications and foci of air can be difficult, especially if a D&C has been attempted prior to the ultrasound21 (Fig. 21–6). Sonohysterography was helpful in two small series by demonstrating an attached endometrial mass in cases of RPOC in distinction to free-floating clot.24,2 Figure 21–4 Range of normal findings postpartum from vaginal delivery. (A,B) Typical uterine enlargement in a patient presenting with bleeding on postpartum day 5, with the fundus retroflexed over the sacrum and extending above the level of the aortic bifurcation, as seen on the transverse image (between calipers, in A) (B). Note the thin (6 mm) echogenic endometrial stripe in the corpus and hypoechoic material in lower uterine segment. (C) Transvaginal scan of the uterus [same patient as (A) and (B)] with color Doppler shows avascular material in the lower uterine segment consistent with clot and/or decidua. (D)

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Evaluation

Ultrasound and Imaging Technique

Normal Postpartum Pelvis

Retained Products of Conception

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree