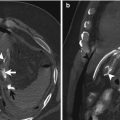

Fig. 10.1

A 24-year-old male patient admitted to the emergency department after a blunt abdominal trauma (motor vehicle accident). (a) Plain film radiograph, upright view, shows scarce amount of air within the small bowel, with clear evidence of the psoas muscle’s outline consistent with reflex spastic ileus. (b, c) Contrast-enhanced axial scan shows small amount of free fluid within the peritoneal cavity and absence of air. (d–f) Contrast-enhanced follow-up CT study (wide window) performed 24 h later depicts evidence of small amount of free air and fluid. The patient was sent to the operating room. At surgery, a traumatic small bowel perforation was found

Nonphysiologic amounts of free intraperitoneal fluid (>75 ml in minimally resuscitated women of child bearing age, >25 ml in minimally resuscitated adult males, and >25 ml in children) without evidence for intraperitoneal solid organ injury suggest occult hollow viscus injury [28].

The distribution of fluid collections may indicate the injured structure [28]: while the hemoperitoneum from laceration of the liver or spleen is classically distributed in the subphrenic spaces, along the parieto-colic gutters and in the pelvis, in the case of a mesenteric or intestinal injury, fluid is more frequently observed among the loops and within the mesenteric folds, forming typical polygonal-shaped collections. In the case of a serosal laceration, in fact, the blood spreads through the mesenteric folds with a V-shaped morphology, with the base corresponding to the loop and the apex to the mesenteric root [23]. Fluid from laceration of a retroperitoneal hollow viscus tends to remain localized close to the site of injury [3, 29].

Origin of a peritoneal fluid may be also deduced from its densitometric characteristics: a low-density collection (average values of density lower than 20 HU, comparable to those of the bile inside the gallbladder or of the urine in the bladder) suggests the spillage of fluid from the intestine; a medium-density collection (>25 HU) is generally consisting largely of extravasated blood; a high-density collection (>120 HU) is attributable to the extravasation of contrast medium from damaged vessels or to the spillage of oral contrast material through bowel wall tears [28]. Notwithstanding these general assumptions, densitometric values do not have an absolute diagnostic value: a blood collection, for example, can appear with reduced density because of decreased hematocrit or the admixture with other fluids of lesser density (e.g., ascites, bile, urine) [20].

10.5.2.3 Extraluminal Air Collection (Intraperitoneal, Mesenteric, or Retroperitoneal)

Free extraluminal air represents a nonspecific but highly suggestive sign of intestinal injury from BAT; when observed, even in the absence of specific signs (interrupted intestinal wall, extraluminal spillage of enteric contents, intramural hematoma), the diagnostic hypothesis bowel injury should always be sought [9, 24]. Coexistent ancillary signs such as bowel wall thickening, abnormalities of parietal enhancement, free peritoneal fluid, and mesenteric infiltration may strengthen the diagnostic suspicion (Fig. 10.2) [25].

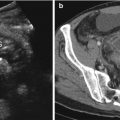

Fig. 10.2

Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan in a patient with blunt thoracoabdominal trauma shows asymmetric wall thickening of the medial aspect of the cecal wall associated with perivisceral soft tissue haziness. Note also the presence of free air with a typical triangular appearance (arrows). CT findings consisting with cecal perforated hematoma, confirmed at surgery

Extraluminal air collection is subdivided into free floating air (pneumoperitoneum and retroperitoneum) and mottled air bubbles (air entrapped within mesenteric layers).

Free floating peritoneal air is typically localized right off of the anterior abdominal wall or along the anterior surface of the liver and spleen, being easily identifiable even in small quantities [3, 23].

Mottled air bubbles indicate air nuclei confined inside the mesenteric sheets, into the lumen of the mesenteric and portal veins, in the thickness of the intestinal wall, or right off of a gas-filled hollow viscus. Their detection is more challenging and time-consuming, justifying the limited overall sensitivity reported in the literature for free air at computed tomography (44–55 %) [23, 24]. In these cases, detection of the small air bubbles may be difficult and time-consuming.

Mottled air bubbles, especially if adjacent to a bowel loop, have higher positive predictive value for intestinal lesion than free floating peritoneal air. This sign may suggest the location of bowel injury (Fig. 10.3) [4, 28].

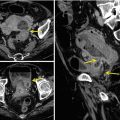

Fig. 10.3

Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows very small gas bubbles (arrow heads) in the peritoneal cavity, consisting with traumatic perforation of the adjacent bowel loop. This case outlines the importance of a careful assessment of the peritoneal cavity with a wide window setting

A traumatic perforation of the duodenum and of the dorsal sides of the ascending and descending colon causes a pneumoretroperitoneum: extraluminal air extends through the fascial planes and may dissect them, being so detectable even at a great distance from the site of perforation [10, 29].

10.5.2.4 Associated Mesenteric Anomalies

This minor CT sign of combined intestinal and mesenteric traumatic injury, represented by striae of inhomogeneous increase of the density of mesenteric fat, is caused by small hemorrhages within the mesentery.

Low specificity is reported for this finding, since it may be associated with both major and minor mesenteric lesions or bowel isolated lesion [30].

10.5.3 Ancillary Signs

10.5.3.1 Intramural Hematoma

Intramural hematoma represents a specific finding, difficult to detect in most of the cases, being recognized only after a careful retrospective analysis of the cases as an abnormal parietal mass [25].

Identification is more frequent in duodenal injuries (for its peculiar anatomical position, a direct force may crush the viscus against the vertebrae, as frequently happens in childhood traumas from bicycle’s handlebars [5, 6] or in adults in traumas from steering wheels), rare in colonic lesions [10].

Flexion-distraction fractures of L1–L2 (Chance fracture) have been reported in association with duodenal intramural hematomas [10].

In the case of duodenal involvement, bowel thickening may be observed in association with fluid in the anterior pararenal space, making it challenging to differentiate a wall hematoma from a traumatic duodenal perforation in the absence of a frank perforation. Only the detection of free air in the anterior pararenal space addresses the diagnosis of perforation of the duodenum [10, 29].

Treatment is usually conservative: the hematoma resolves spontaneously within 3 weeks. In a limited percentage of cases, complications are observed at a medium to long term, most often in the form of luminal stenosis or obstruction [2].

10.5.3.2 Segmental/Focal Bowel Wall Thickening

Disproportionate circumferential thickening compared with the normal bowel segment and bowel wall thickness >3 mm is considered a nonspecific but significantly more sensitive sign of bowel traumatic injury compared to free air and extravasated oral contrast medium, being appreciable in approximately 75 % of full-thickness lacerations [24, 28, 31]. The associated finding of intramural air makes increases the specificity of wall thickening, making also likely the possibility of a full-thickness laceration [29].

10.5.3.3 Abnormal Bowel Wall Enhancement

Unequivocal focal abnormal enhancement (decreased or increased) of a segment of the bowel is a highly suspicious finding often associated with a significant injury especially if associated with a pocket of fluid in the adjacent mesentery or free fluid in the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 10.4) [20].

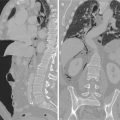

Fig. 10.4

Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows focal hyper-enhancement of the distal ileum. This CT finding is nonspecific and requires clinical correlation

Vascular supply to a loop may be compromised by traumatic intestinal or mesenteric lesions: consequent hypoperfusion can paradoxically manifest itself as increased wall enhancement in the early stages due to the passage of molecules of the contrast medium through the more permeable damaged vascular endothelium.

Bowel wall density may be evaluated compared to that of the psoas muscle or of the contiguous vessels [32]. Patchy, irregular areas of increased impregnation of contrast medium represent a nonspecific sign of full-thickness laceration. Conversely, areas of decreased or absent bowel wall enhancement indicate traumatic bowel ischemia due to mesenteric vascular laceration [20].

10.6 CT Signs of Major Primary Mesenteric Injuries in BAT

Spectrum of primary mesenteric traumatic injuries includes conditions potentially associated with bowel primary or secondary involvement. Avulsion of the meso, active contrast medium extravasation, and mesenteric hematoma represent specific CT signs of mesenteric bowel injury. Nonspecific signs include mesenteric infarction and fluid collections [24, 30].

10.6.1 Mesenteric Avulsion

10.6.2 Active Hemorrhagic Extravasation

Traumatic laceration of the meso associated with mesenteric vessel rupture leads to hemorrhage and subsequent necrosis of the intestine, deprived of its vascular supply. The discontinuity of the vessel wall is demonstrated by the appearance of a blush of contrast medium along the course of the vessel circumscribed by a halo of tenuous hyperdensity, corresponding to the hematoma. This CT sign is characterized by 100 % specificity [30], representing an absolute indication for urgent operative treatment and frequently associating with major traumatic lesions of the bowel walls.

10.6.3 Mesenteric Hematoma

Contained vascular lesions usually lead to the formation of mesenteric hematomas. In the absence of an active bleeding, the treatment of such entities is conservative. However, large hematomas may compress vascular structures leading to ischemic changes of the intestine [30, 32].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree