Benign esophageal tumors are 50-fold less common than esophageal carcinomas. These are predominantly

leimyomas,

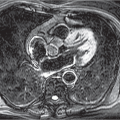

12 which are intramural tumors that originate from the smooth muscle cells and exhibit hardly any circumferential growth. They can become very large and gradually cause progressive dysphagia. On

CT and

MRI, they manifest as smoothly marginated and homogeneous masses. Occasionally, calcifications are seen.

13Duplication cysts, the second most common benign masses, become symptomatic already in childhood. On sectional imaging, the typical features of a fluid-filled cyst can be identified. These are filled with air if they communicate with the esophagus.

13

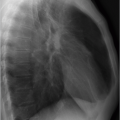

In the vast majority of cases, the most common malignant tumor of the esophagus,

esophageal carcinoma, is found on histology to be a squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma (▶

Fig. 12.6). Smoking and alcohol abuse are the main risk factors for esophageal carcinoma. This tumor mainly affects men aged 60 to 70 years. It has a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival of around 10%.

13 Staging is the main focus of imaging in esophageal carcinoma.

CT and

PET-CT are required to rule out distant metastasis as well as for evaluation of invasion of surrounding structures. Only endosonography is able to evaluate tumor extension within the esophagus; it is also superior to other cross-sectional imaging techniques for detection of lymph node metastasis. The tumor stage can be derived from the TNM staging classification (▶

Table 12.2). For some stages, histologic grading is also used in addition to the imaging findings (▶

Table 12.3). Tumor contact with the aorta of more than one-quarter of the vascular circumference (over 90°) is considered a criterion for probable aortic invasion.

14