Chapter 16 Mediastinal Masses

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING WORKUP OF MEDIASTINAL MASSES

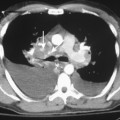

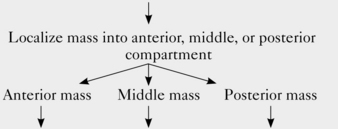

Radiologic examination of a mediastinal mass usually can narrow the differential diagnosis to two or three likely candidates. In some cases, imaging features enable the radiologist to make a specific diagnosis. The radiologic workup depends on the location of the mass (Fig. 16-1 and Box 16-1).

Box 16-1 Algorithm for Imaging Evaluation of Mediastinal Masses

| Mediastinal mass detected on chest radiograph | ||

| ||

| Chest CT | Chest CT (I+)* | MRI or Barium swallow if esophageal origin is suspected |

| Other studies:Gallium scan if Hodgkin’s lymphoma is suspectedRadioiodine scanif thyroid goiter issuspected | Other studies:MRI if there is acontraindicationto contrast and avascular abnormalityis suspected or ifvascular invasionis suspected | |

ANTERIOR MEDIASTINAL MASSES

Thymic Abnormalities

Thymic Epithelial Tumors

The most common thymic abnormality that manifests as an anterior mediastinal mass is thymoma (Box 16-2). Thymomas account for most anterior mediastinal masses in adults and typically occur as incidental findings in otherwise healthy individuals. However, thymomas may be associated with other abnormalities, including myasthenia gravis, red cell aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, and stiff-person syndrome. The association with myasthenia gravis is the most common of the three; about 15% of patients with myasthenia gravis have a thymoma, and about 50% of patients with thymomas have myasthenia gravis.

Box 16-2 Thymoma

DEMOGRAPHICS

Age: usually 40 to 60 years old; unusual in patients younger than 30 years old

Gender: men and women equally affected

Associations: myasthenia gravis, hypogammaglobulinemia, red cell aplasia, and stiff-person syndrome

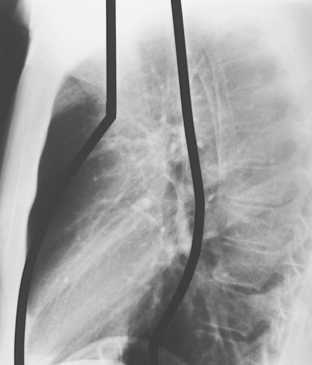

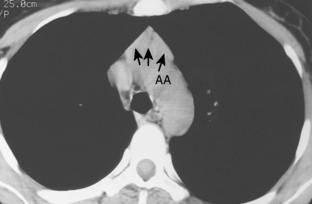

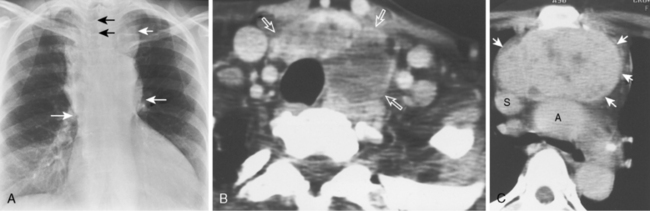

As with other midline anterior mediastinal masses, conventional radiographic findings are often limited to the lateral chest radiograph, which may demonstrate a well-defined mass in the normally clear retrosternal space. Small masses may not be detectable on plain radiographs, but CT can help to identify a thymoma in patients with myasthenia gravis. Characteristic CT imaging features include a well-defined, round, or oval mass, usually of homogeneous soft tissue density, that is located within the anterior mediastinum (Fig. 16-2). Although they are most commonly located anterior to the junction of the heart and great vessels, thymomas may occur at any level from the thoracic inlet to the diaphragm. In about 20% of cases, there is evidence of calcification, which is typically curvilinear.

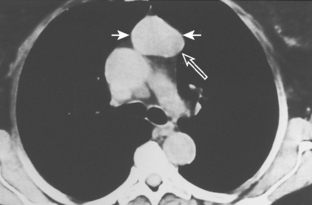

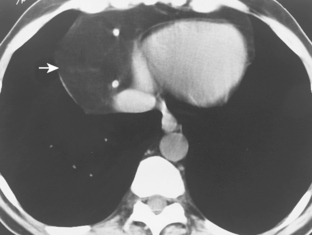

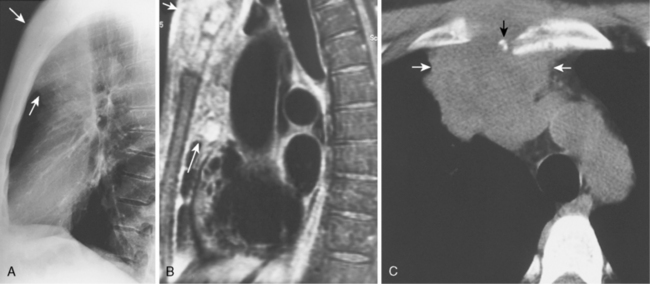

Most thymomas are benign lesions confined within a fibrous capsule, but about 30% of thymomas are more aggressive and demonstrate invasion through the fibrous capsule. The WHO classification scheme correlates with the likelihood of invasiveness, a factor that has an important influence on treatment and prognosis. Types A and AB are usually encapsulated, type B (especially B3) has a greater likelihood of invasiveness, and type C is almost always invasive. Although CT and MRI findings are often of limited value in differentiating histologic subtypes of thymic epithelial neoplasms, certain findings have predictive value. For example, a small, smooth, round, homogeneous anterior mediastinal mass usually corresponds to a type A thymoma, whereas irregular contours and heterogeneous attenuation favor a type C thymic carcinoma (Fig. 16-3). Calcification is most commonly observed in type B thymomas and type C thymic carcinoma.

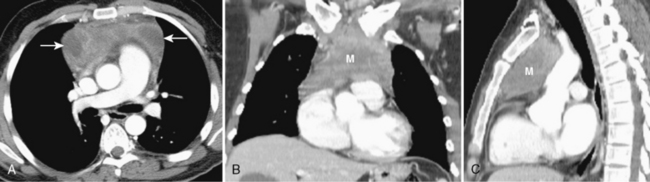

When interpreting CT scans or MRI studies of patients with suspected or proven thymic neoplasms, signs of capsular invasion or extracapsular extension should be carefully sought. They include irregular tumor margins; invasion of surrounding mediastinal fat, vascular structures, or chest wall; and irregular interface with the adjacent lung. Invasive thymomas typically spread locally (Fig. 16-4), and metastases outside of the thorax are rare. Pleural dissemination, also referred to as drop metastases, and pericardial involvement are common, whereas lung metastases are rare. The extent of involvement by thymic neoplasms is often best determined by viewing CT or MRI data in axial, sagittal, and coronal planes rather than relying solely on axial images (see Fig. 16-3).

Thymic Hyperplasia

Thymic hyperplasia (Box 16-3) is associated with a wide variety of systemic abnormalities, including hyperthyroidism. Rebound thymic hyperplasia may be seen in patients who have been treated with chemotherapy.

Thymic hyperplasia is usually identified on CT as enlargement of the thymus gland, which maintains its normal bilobed, arrowhead configuration (Fig. 16-5). In contrast, most other thymic abnormalities appear as a discrete mass rather than as uniform glandular enlargement. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is of limited value in differentiating thymic hyperplasia from thymic neoplasms because both may demonstrate FDG avidity. MRI imaging using a chemical shift technique can reliably differentiate thymic hyperplasia from thymic neoplasms. On chemical shift imaging, thymic hyperplasia is associated with a characteristic decrease in signal intensity within the thymus gland.

Thymolipoma

Because of their soft, pliable nature, thymolipomas commonly drape around the heart and other mediastinal structures. They are often quite large at the time of presentation, and they may mimic cardiac enlargement on chest radiographs. Identification of fat within the mass on CT or MRI suggests the diagnosis (Fig. 16-6).

Primary Mediastinal Lymphoma

Primary mediastinal lymphoma (Box 16-4) refers to malignant lymphoma that is exclusively or mostly limited to the mediastinum. The most common cell types to arise in the anterior mediastinum include the nodular sclerosing subtype of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, and lymphoblastic lymphoma.

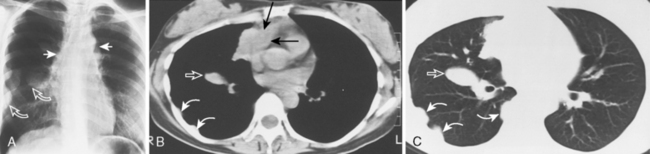

Box 16-4 Primary Mediastinal Lymphoma

Approximately 40% of these patients present with enlargement of a single anterior mediastinal nodal group. Imaging features vary, ranging from a single, spherical soft tissue mass in the anterior mediastinum to a large, lobulated mass representing a conglomeration of lymph nodes. CT may show a mass with homogeneous soft tissue density, or it may appear heterogeneous, in which the low-attenuation areas represent necrosis. Whereas anterior mediastinal masses from lymphoma typically demonstrate well-defined margins, invasion of adjacent lung parenchyma may result in irregular margins. Invasion into the chest wall may also occur (Fig. 16-7).

Germ Cell Neoplasms

There are a variety of benign and malignant GCNs (Box 16-5). Seventy percent of GCNs are benign, comprising mostly teratomas and dermoid cysts. Dermoid cysts contain only ectodermal layer elements, but teratomas contain elements of all three germinal layers. Several types of malignant GCNs occur within the anterior mediastinum, including pure seminomas and several nonseminomatous tumors (i.e., choriocarcinoma; embryonal cell carcinoma, yolk sac tumors, and mixed GCNs). Teratomas usually are benign, but carcinoma may rarely develop within one of the germinal layer elements.

Box 16-5 Germ Cell Neoplasms

DEMOGRAPHICS

Age: young patients, usually in third decade

Gender: malignant germ cell neoplasms have marked male predominance

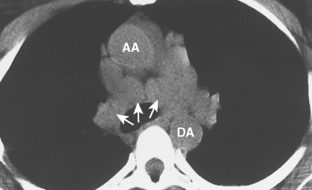

Dermoid cysts and teratomas have similar imaging features. They typically appear as heterogeneous, sharply marginated, multiloculated, cystic, anterior mediastinal masses. A combination of fluid, fat, and calcification is frequently observed. This unique combination of findings makes teratoma one of the few mediastinal tumors that can confidently be diagnosed by radiographic findings alone. A fat-fluid level is seen in 10% of cases and is highly specific for teratoma (Fig 16-8). The identification of dental tissue, such as a well-formed tooth, is rare, but it is also diagnostic of this entity. If a dominant, solid soft tissue component is observed within the mass, a malignant GCN or a teratoma with malignant components should be considered in the diagnosis.

Thyroid Abnormalities

Thyroid abnormalities account for most thoracic inlet masses in adults (Box 16-6). They may extend inferiorly into the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments of the mediastinum. When located in the anterior mediastinum, thyroid masses are almost always located posterior to the great vessels, usually in a paratracheal location. However, most other anterior mediastinal masses are located anterior to the great vessels, and a mediastinal mass located anterior to the great vessels in a retrosternal location is unlikely to be of thyroid origin.

BOX 16-6 Thyroid Masses

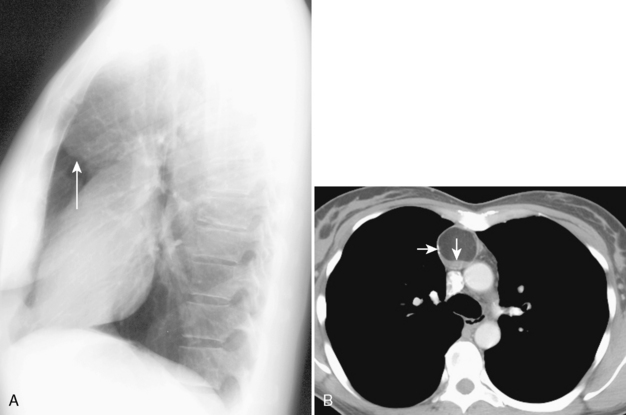

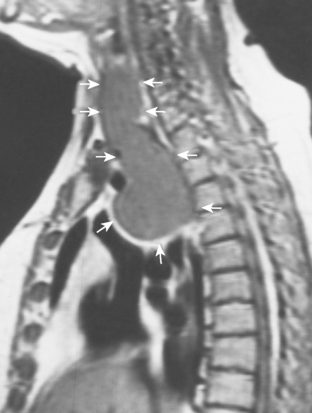

The most important of these features is demonstration of continuity of the mass with the cervical thyroid gland. A combined CT examination of the lower neck and chest is best (Fig. 16-9), although MRI can be used (Fig. 16-10). A radioiodine scan may be confirmatory, with demonstration of radioiodine uptake from foci of functioning thyroid tissue within the mass.

MIDDLE MEDIASTINAL MASSES

Lymphadenopathy

Neoplastic, inflammatory, or infectious lymphadenopathy (Box 16-7) is the most common cause of a middle mediastinal mass (Box 16-8). It is therefore no surprise that there are no distinguishing demographic features.

Box 16-8 Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy Differential Diagnosis

INFECTIOUS CAUSES

Fungal infection (especially histoplasmosis)

Viral infection (measles, infectious mononucleosis)†

Lymphadenopathy should be considered in assessing a middle mediastinal mass when the mass is localized to a known anatomic lymph node site, such as the azygous, subcarinal, or aortopulmonary window regions. Lymphadenopathy often manifests as multiple, discrete masses (Fig. 16-11), in contrast to most other causes of mediastinal masses, which usually manifest as a single mass. Multiple masses within known anatomic lymph node sites suggest lymphadenopathy.

CT plays a role in detecting and characterizing lymph nodes. Although lymph nodes often appear as homogeneous soft tissue density on CT, they may also demonstrate calcification, low-density centers, or vascular enhancement. Identification of these lymph node characteristics can shorten the lengthy differential diagnosis of mediastinal lymphadenopathy (Box 16-9).