LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. State the anatomic boundaries of the anterior, middle, posterior, and superior mediastinum.

2. Name the four most common causes of an anterior mediastinal mass; localize a mass in the anterior mediastinum on a chest radiograph and chest computed tomographic (CT) scan.

3. Name the three most common causes of a middle mediastinal mass; localize a mass in the middle mediastinum on a chest radiograph and chest CT scan.

4. Name the most common cause of a posterior mediastinal mass; localize a mass in the posterior mediastinum on a chest radiograph and chest CT scan.

5. Name five etiologies of bilateral hilar lymph node enlargement.

6. State the three most common locations (Garland triad) of thoracic lymph node enlargement in sarcoidosis.

7. Recognize a cystic mass in the mediastinum on chest CT, and suggest the possible diagnosis of a bronchogenic, pericardial, thymic, or esophageal duplication cyst.

8. Describe and recognize the findings of fibrosing mediastinitis on chest CT.

The mediastinum includes all the structures and organs located between the two lungs. Because the mediastinum is invested by the medial parietal pleura, a mass isolated to the mediastinum will generally have a smooth contour (created by the pleural surface). Lung parenchymal masses, on the other hand, are not surrounded by pleura and may therefore have an irregular contour. Mediastinal masses can be recognized on chest radiographs when there is an abnormal contour to the normal mediastinal structures. On the right, these normal structures include, from superior to inferior, the brachiocephalic vessels, superior vena cava, azygos arch, ascending aorta, and right atrium. On the left, the mediastinal contour, from superior to inferior, is made up of the brachiocephalic vessels, aortic arch, main pulmonary artery, and left ventricle. On the lateral chest radiograph, the mediastinum extends from the inner margin of the sternum to the inner margins of the posterior ribs.

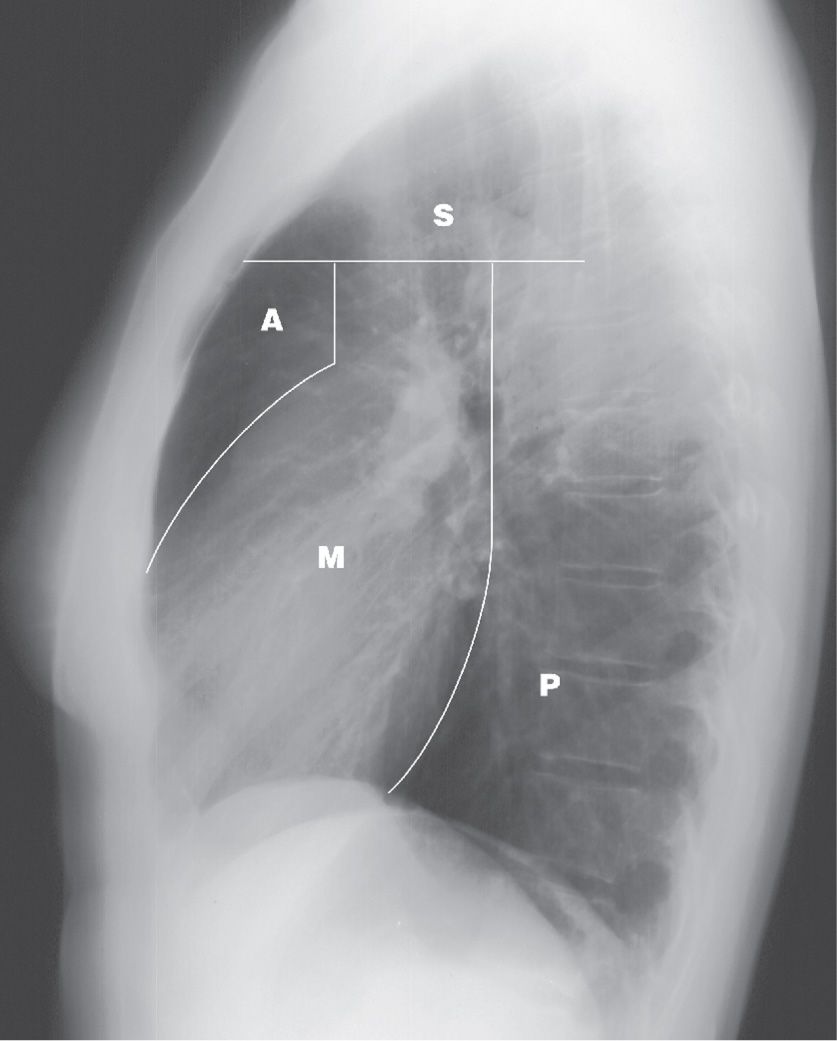

The mediastinum can be divided into compartments, and many classification systems have been devised to simplify the differential diagnosis when an abnormality is seen in one or more compartments. A commonly used system based on anatomic subdivisions (the superior, anterior, middle, and posterior mediastinal compartments) will be used in this chapter (Fig. 6.1). Approximately 60% of all mediastinal masses arise in the anterior mediastinum, 25% appear in the posterior mediastinum, and 15% occur in the middle mediastinum (1). When an abnormality is not isolated to one mediastinal compartment, as is often the case with large mediastinal masses, the list of diagnostic possibilities can be determined by localizing the abnormality to the mediastinal compartment serving as the “epicenter” of the abnormality or by considering all abnormalities that occur in the compartments involved. Associated radiologic findings can also help to narrow the list of diagnostic possibilities; these include deviation of the trachea (commonly seen with thyroid masses); presence of axillary, abdominal, and retroperitoneal adenopathy (suggesting the diagnosis of lymphoma); or posterior rib erosion or destruction (consistent with a posterior mediastinal mass, such as a neurogenic tumor).

FIG. 6.1 • Mediastinal compartments. Lateral chest radiograph shows the boundaries delineating the superior (S), anterior (A), middle (M), and posterior (P) mediastinal compartments.

SUPERIOR MEDIASTINUM

The superior mediastinum is bounded above by the thoracic inlet and below by a line from the sternomanubrial joint to the fourth thoracic vertebral body. The other mediastinal compartments lie inferior to this line. Abnormalities in the superior mediastinum include masses that extend down into the upper mediastinum from the neck, such as thyroid goiters or cystic hygromas; mediastinal adenopathy; and vascular abnormalities, such as aneurysms.

Table 6.1 ANTERIOR MEDIASTINAL MASSES

“4 Ts”

Thymoma (generally over age 40)

Teratoma (and other germ cell tumors, generally under age 40)

Thyroid (goiter or neoplasm, look for tracheal deviation)

Terrible lymphoma (or Thomas Hodgkin lymphoma)

ANTERIOR MEDIASTINUM

Also referred to as the prevascular space, the anterior mediastinum is bounded above by the superior mediastinum, laterally by pleura, anteriorly by the sternum, and posteriorly by the pericardium and great vessels. This compartment contains areolar tissue, lymph nodes, lymphatic vessels, thymus gland, ectopic thyroid and parathyroid glands, and internal mammary arteries and veins.

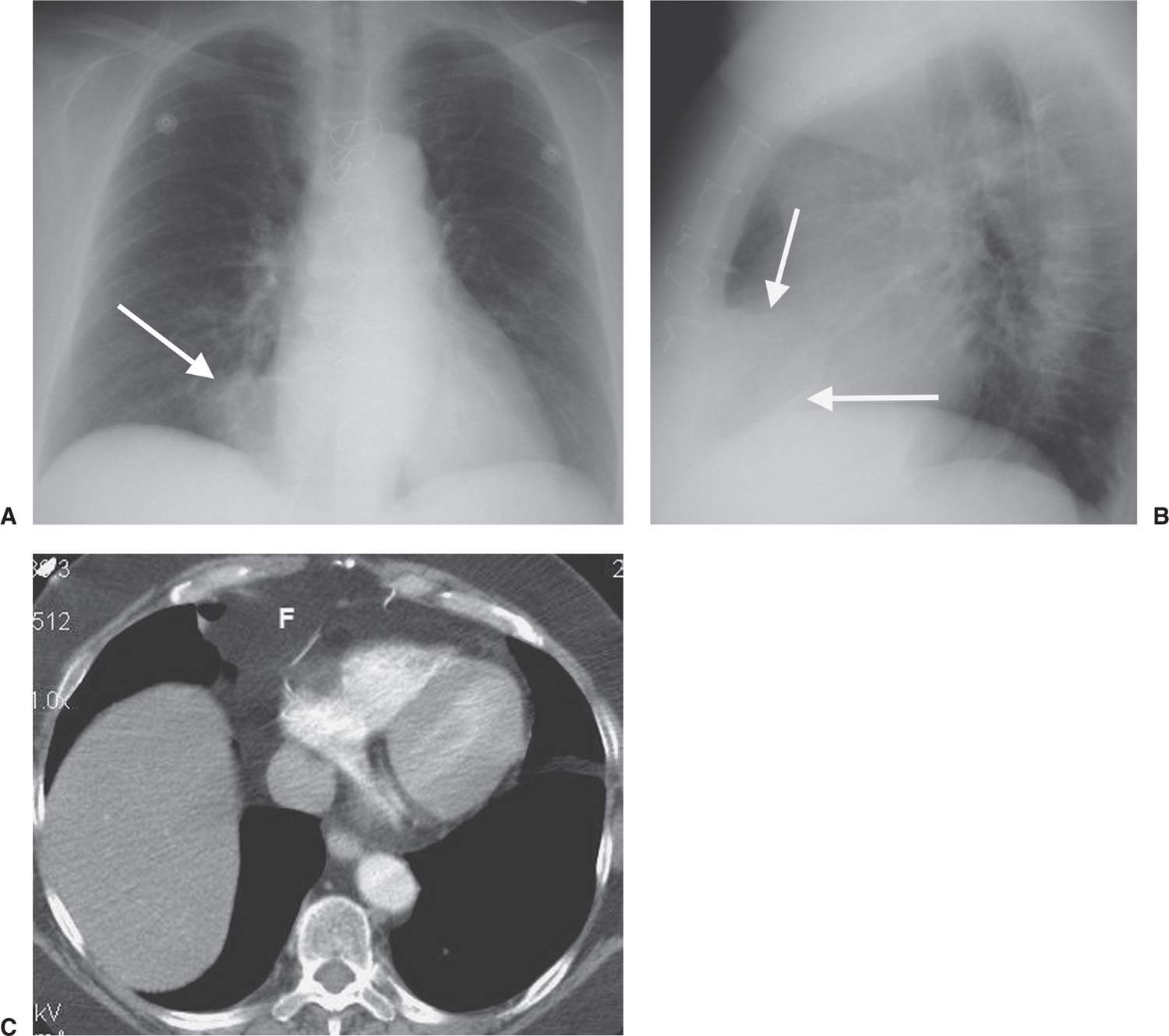

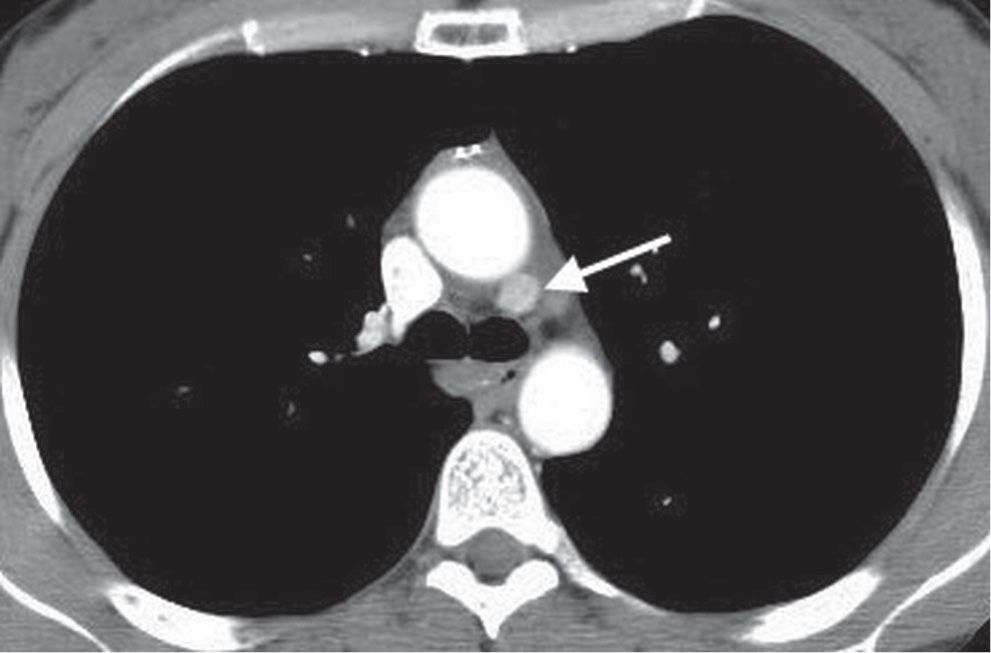

Masses occurring in the anterior mediastinum are listed in Table 6.1. In addition to the “4 Ts” (thymoma, thyroid mass, teratoma, and terrible lymphoma), which account for the great majority of lesions, there are many other less common causes of an anterior mediastinal mass. These include vascular tortuosity or aneurysm, cardiac tumors or prominent pericardiac fat (Fig. 6.2), cystic hygroma, bronchogenic cyst, pericardial cyst, hemangioma, lymphangioma, parathyroid adenoma (Figs. 6.3 and (6.4), various other mesenchymal tumors (e.g., fibroma or lipoma), sternal tumor, primary lung tumor invading the anterior mediastinum, Morgagni hernia (Fig. 6.5), abscess (Fig. 6.6), and mediastinal lipomatosis (Fig. 6.7).

An intrathoracic thyroid mass is usually a benign multinodular goiter that originates in the neck and extends downward into the mediastinum through the thoracic inlet. This continuity is an important diagnostic feature on chest radiography. Many thyroid masses displace or narrow the trachea (Figs. 6.8 to 6.10). Another useful sign of a thyroid mass is the relative high attenuation value of the thyroid tissue, at least 20 Hounsfield units above that seen in adjacent muscles on both precontrast and postcontrast computed tomographic (CT) images (2). CT scans can show cystic components. Calcification is common and usually caused by benign disease when it is dense, amorphous, and well defined with a nodular, curvilinear, or circular configuration. Distinguishing between benign and malignant thyroid masses on chest radiography or CT scanning is not possible unless the tumor has clearly spread beyond the thyroid gland (indicating malignancy). Malignant thyroid masses can also have calcifications, generally with a configuration of fine dots grouped in a cloudlike formation (3–5). However, the patterns of benign and malignant calcifications serve as general guidelines, and malignant medullary thyroid carcinoma can contain well-defined, occasionally ring-shaped, dense calcifications that are similar in appearance to the calcifications seen with benign thyroid goiter. Radionuclide imaging is a very sensitive and specific method of determining the thyroid nature of an intrathoracic mass, but CT provides more information about the mass.

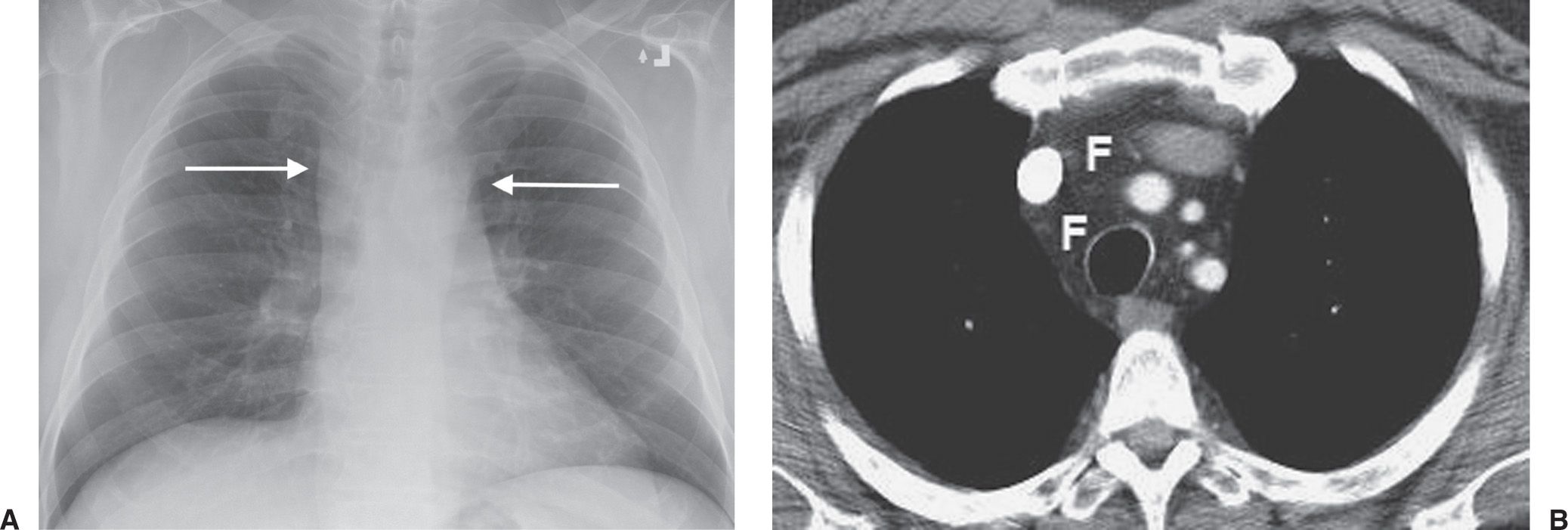

FIG. 6.2 • Prominent pericardial fat. A: Posteroanterior (PA) chest radiograph shows a round mass at the right cardiophrenic angle (arrow) that is less opaque than the adjacent heart. B: Lateral view shows that the mass is projected over the anterior–inferior heart (arrows) in the typical location of pericardial fat. C: CT shows this mass to be of fat attenuation (F), similar to that of the subcutaneous fat.

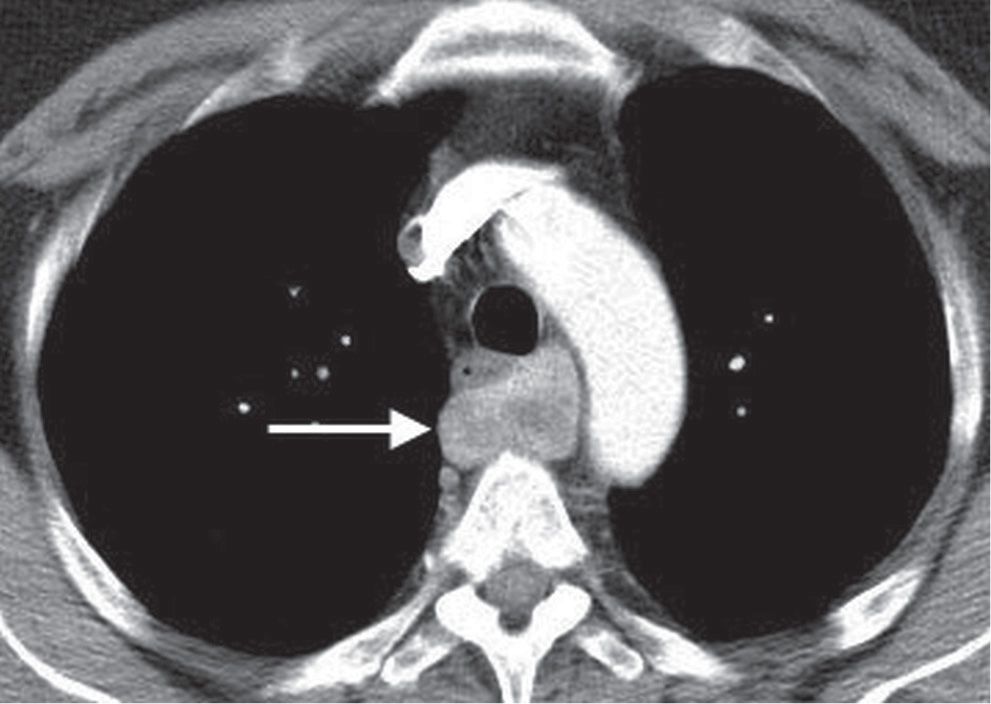

FIG. 6.3 • Parathyroid adenoma. CT shows an enhancing mass in the aortopulmonary window (arrow). Although commonly an anterior mediastinal mass, parathyroid adenomas can occur in any mediastinal compartment.

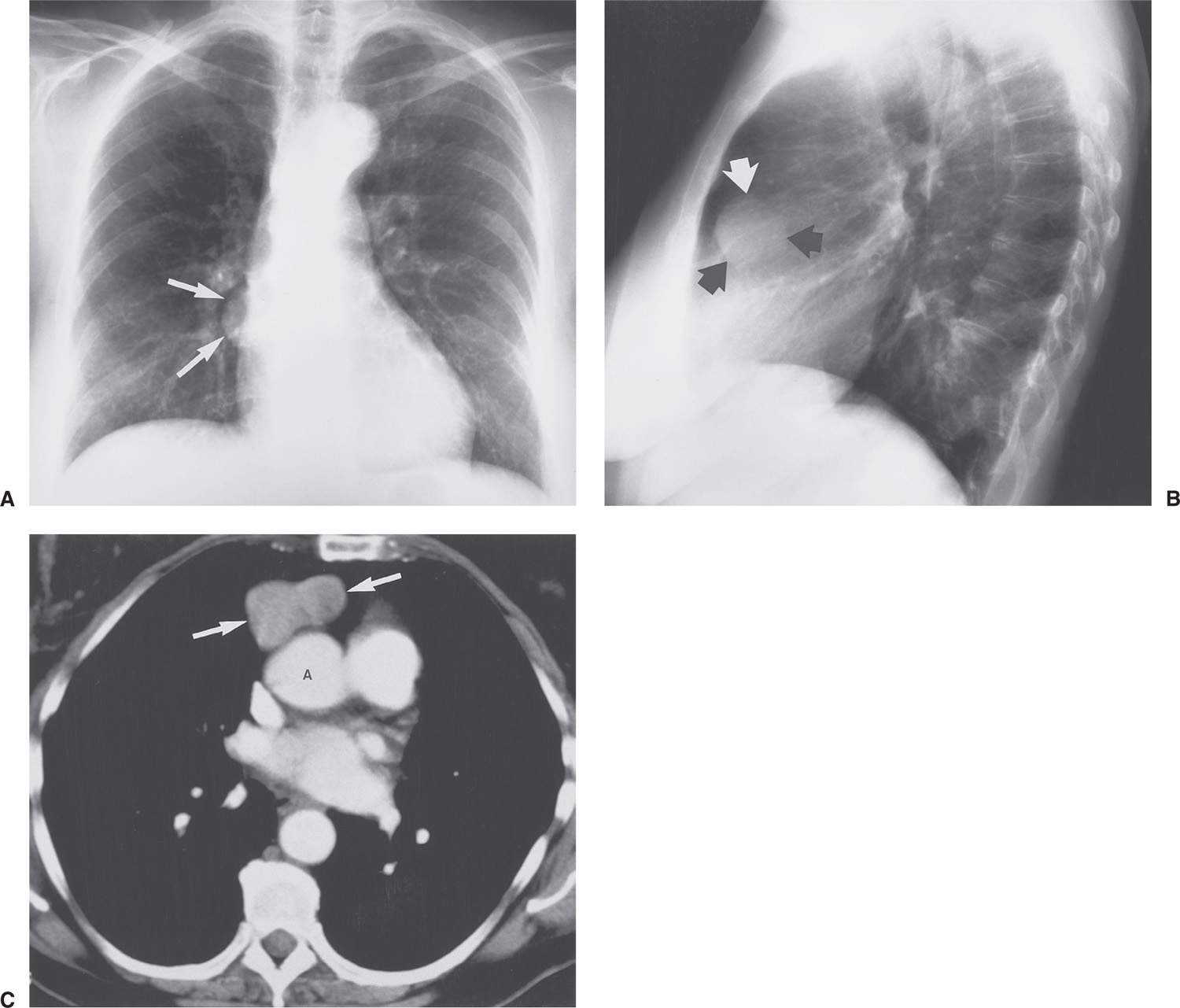

Thymomas are tumors consisting of thymic epithelial cells and reactive lymphocytes, with noninvasive or invasive patterns of growth (6). The presence or absence of tumor spread beyond the capsule (usually determined surgically), rather than the histologic appearance within the thymus, determines whether a tumor is benign or malignant. Thymomas occur at an average age of 50 years and with equal frequency in men and women (6). They are associated with a variety of autoimmune diseases, most notably myasthenia gravis. Approximately 40% of patients with thymoma have myasthenia gravis, and the incidence of thymoma in patients with this disease is approximately 15% (7). Most thymomas arise in the upper anterior mediastinum, anterior to the ascending aorta above the right ventricular outflow tract and main pulmonary artery (Figs. 6.11 and (6.12). They can extend into the adjacent middle or posterior mediastinum, and they can occur or extend into the lower third of the mediastinum, as low as the cardiophrenic angles. Punctate, curvilinear, or ringlike calcification is common in both benign and invasive thymomas (8). On a CT scan, thymomas are usually of homogeneous attenuation and show uniform enhancement, but rarely they can appear cystic with discrete nodular components (Fig. 6.13). In patients under age 40, diagnosing a small thymoma can be difficult because the normal gland is variable in size. A normal thymus, in contrast to a thymic neoplasm, conforms to the shape of the adjacent great vessels on CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A neoplasm gives rise to focal thymic enlargement, usually with its center away from the midline, whereas a normal gland is approximately symmetric and maintains a somewhat triangular shape on axial imaging (Fig. 6.14). Invasive thymomas inhabit the mediastinal fat, spreading to the pericardium and pleura. Unless mediastinal invasion has occurred, distinguishing benign from invasive thymoma is not possible with CT scanning. Transpleural spread may manifest as so-called “drop metastases” at a site distant from the primary lesion (Figs. 6.14 and (6.15), and imaging of the entire pleural space and upper abdomen is therefore important. Extensive pleural involvement may mimic malignant mesothelioma. Other less common thymic masses include cyst (Fig. 6.16), abscess, thymolipoma, malignant lymphoma (most notably Hodgkin lymphoma), thymic carcinoid, germ cell tumors, and thymic carcinoma (Fig. 6.17).

FIG. 6.4 • Parathyroid adenoma. CT shows a heterogeneously enhancing mass posterior to the esophagus (arrow).

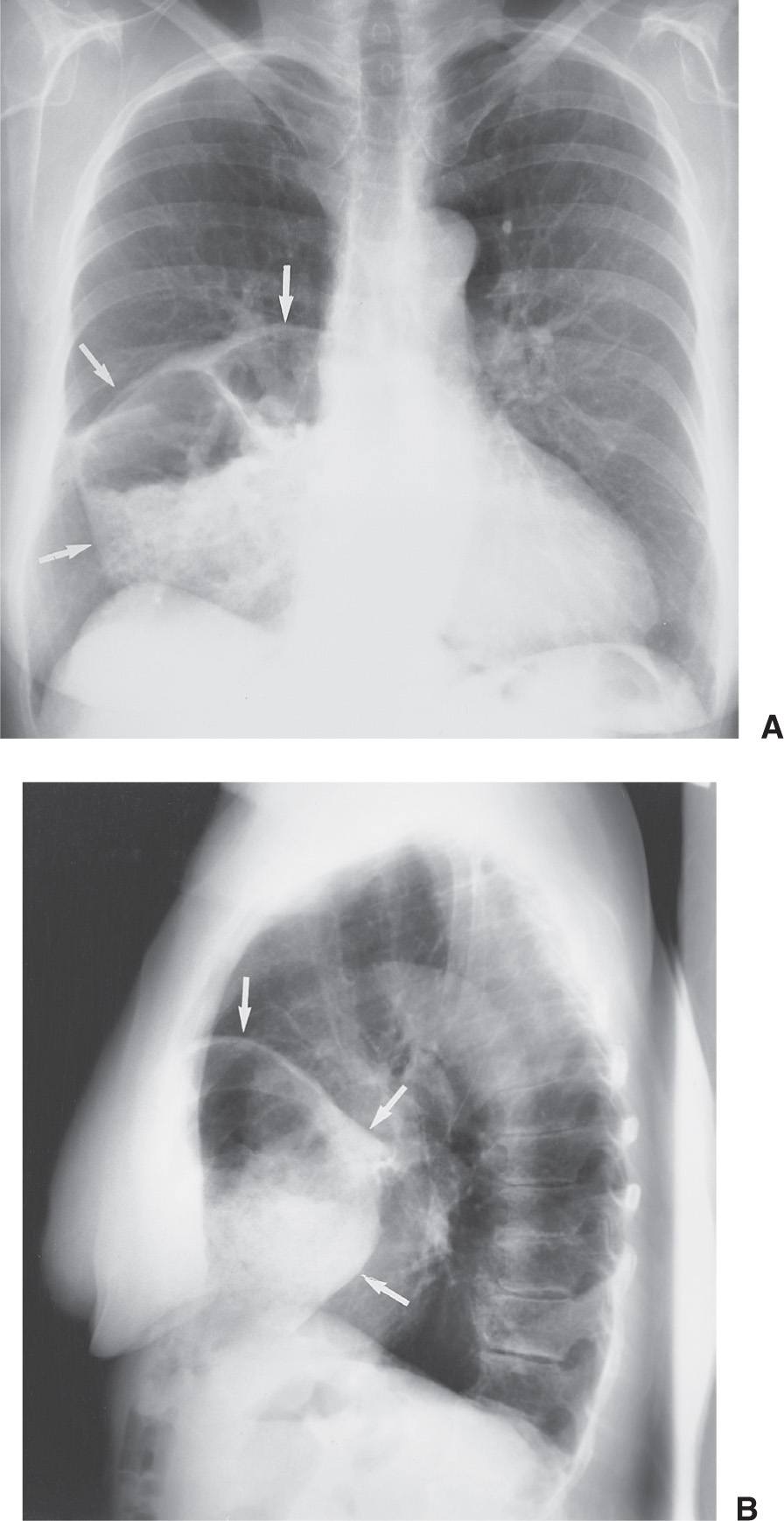

FIG. 6.5 • Morgagni hernia. PA (A) and lateral (B) chest radiographs show colon, filled with air and stool (arrows), herniating into the anterior mediastinum through a congenital defect in the anteromedial diaphragm.

FIG. 6.6 • Anterior mediastinal abscess. CT scan of a 54-year-old man who recently underwent aortic valve replacement shows a loculated fluid collection (A) with an enhancing rim anterior to the ascending aorta and posterior to the sternum.

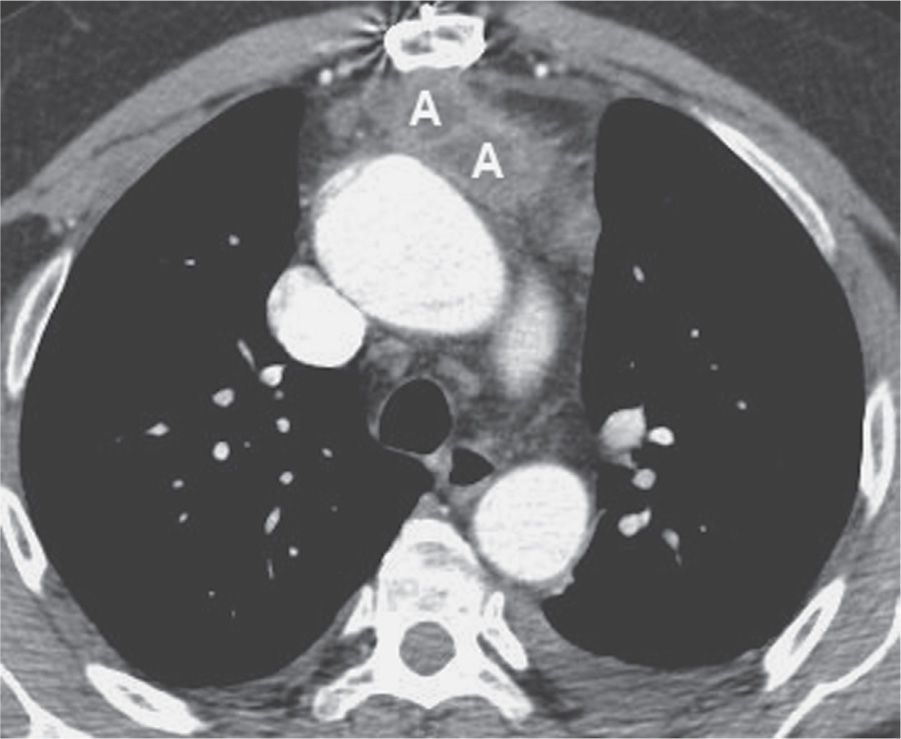

FIG. 6.7 • Mediastinal lipomatosis. A: PA chest radiograph shows an abnormally wide upper mediastinum with straight margins (arrows). B: CT scan shows abundant mediastinal fat (F).

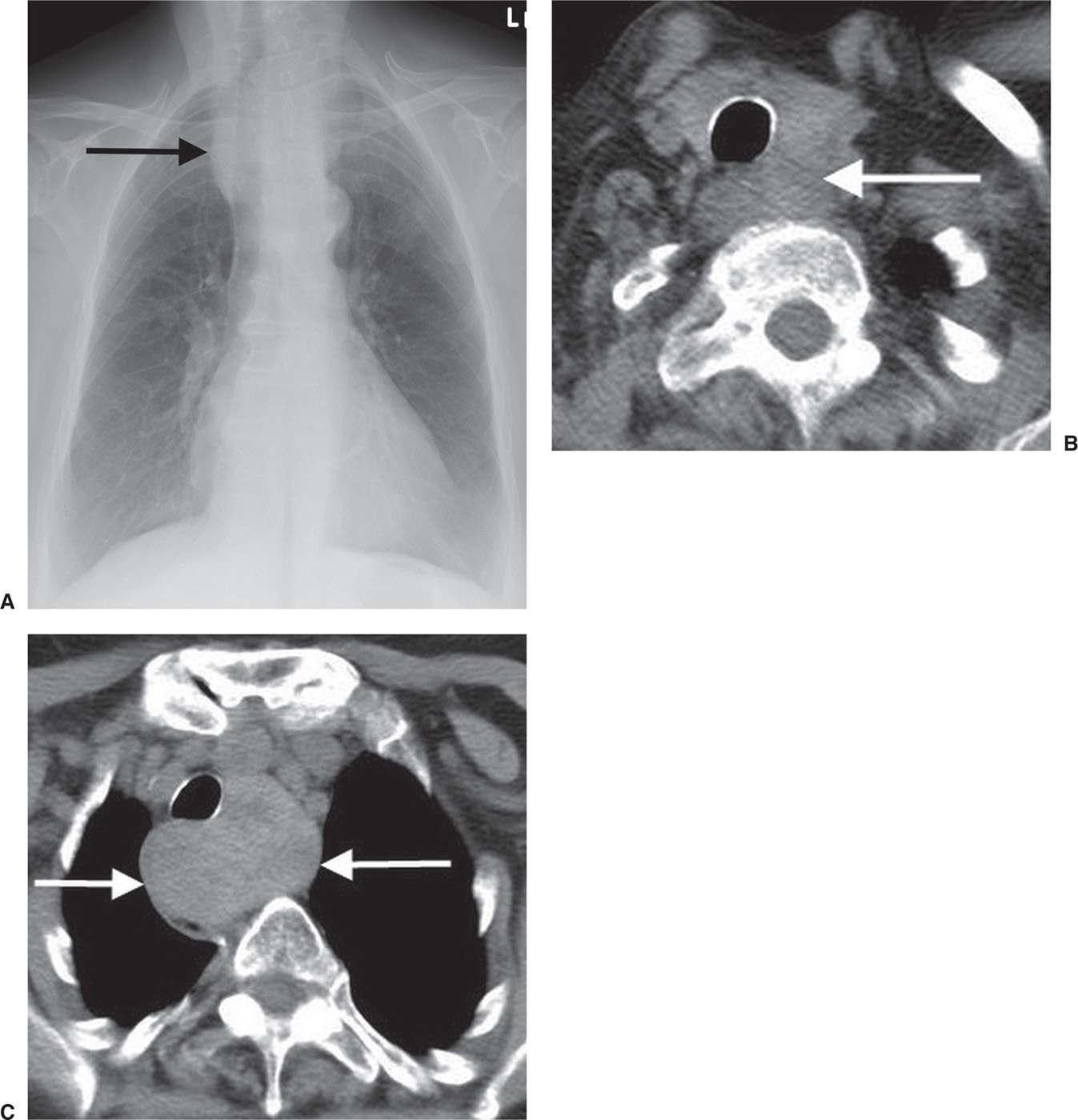

FIG. 6.8 • Thyroid goiter. A: PA chest radiograph shows a widened upper mediastinum (arrow). B: CT scan shows a left thyroid mass (arrow). C: CT scan at a level inferior to (B) shows inferior continuation of the heterogeneous mass (arrows) and rightward deviation of the trachea.

FIG. 6.9 • Thyroid goiter. A: PA chest radiograph shows a mediastinal mass (solid arrows) and deviation of the trachea to the right (dashed arrows). B: Lateral view shows anterior deviation of the trachea (arrow). C: CT scan shows a heterogeneous mass that causes narrowing and rightward deviation of the trachea (solid arrow) and rightward deviation of the esophagus (dashed arrow).

FIG. 6.10 • Follicular neoplasm of the thyroid. A: PA chest radiograph shows a left paratracheal mass and deviation of the trachea to the right (arrow). B: CT scan shows a heterogeneously enhancing left thyroid mass (arrows).

A teratoma is a neoplasm derived from more than one embryonic germ layer. Other germ cell tumors include benign dermoid cyst, malignant seminoma (the most common germ cell tumor), teratocarcinoma, embryonal carcinoma, endodermal sinus tumor (yolk sac tumor) (Fig. 6.18), choriocarcinoma, and mixtures of these types. Germ cell tumors in the mediastinum arise from primitive rest cells and generally are not metastatic from gonadal tumors. Some malignant germ cell tumors secrete beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein, which can be used to diagnose and monitor progression of disease.

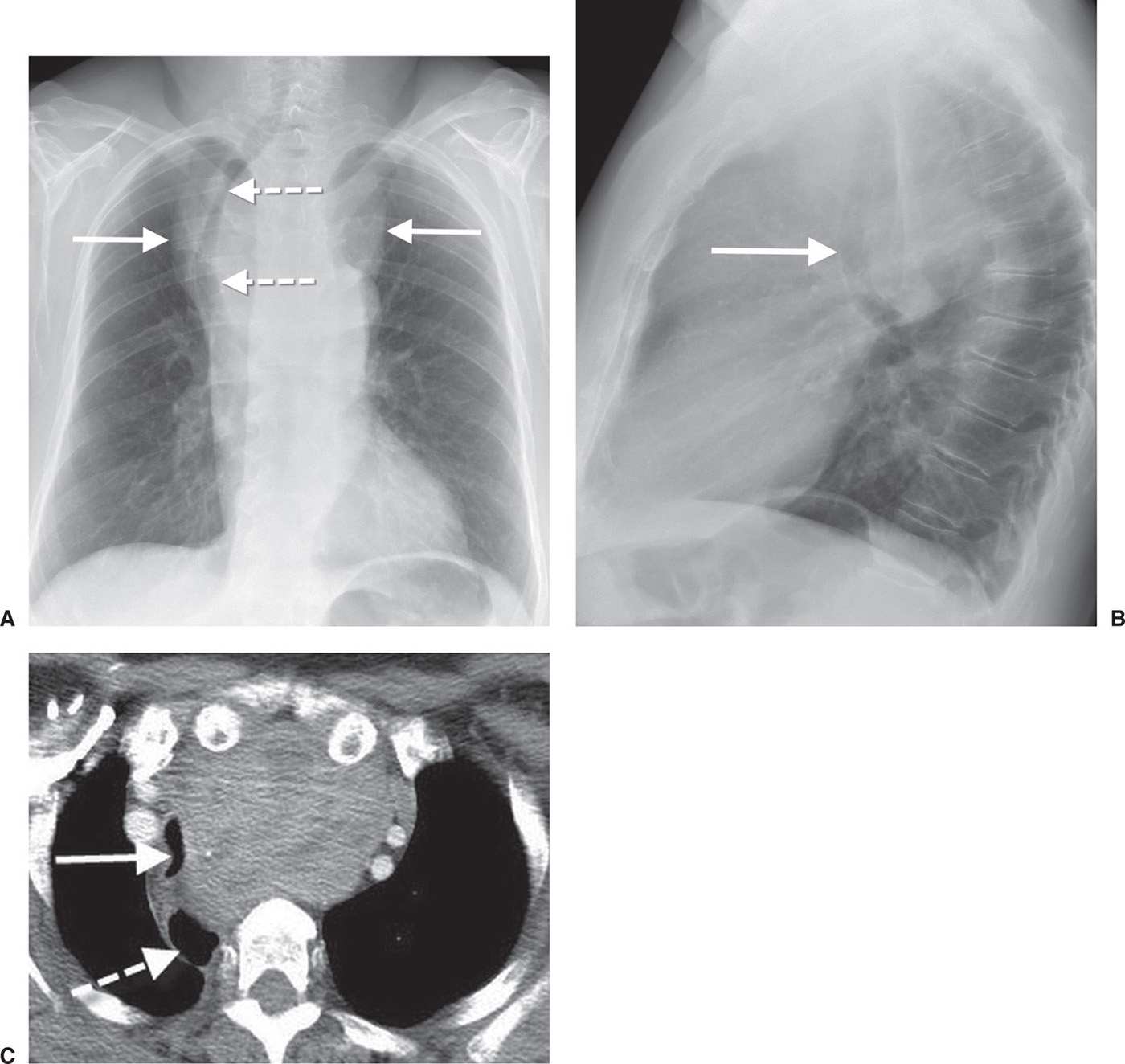

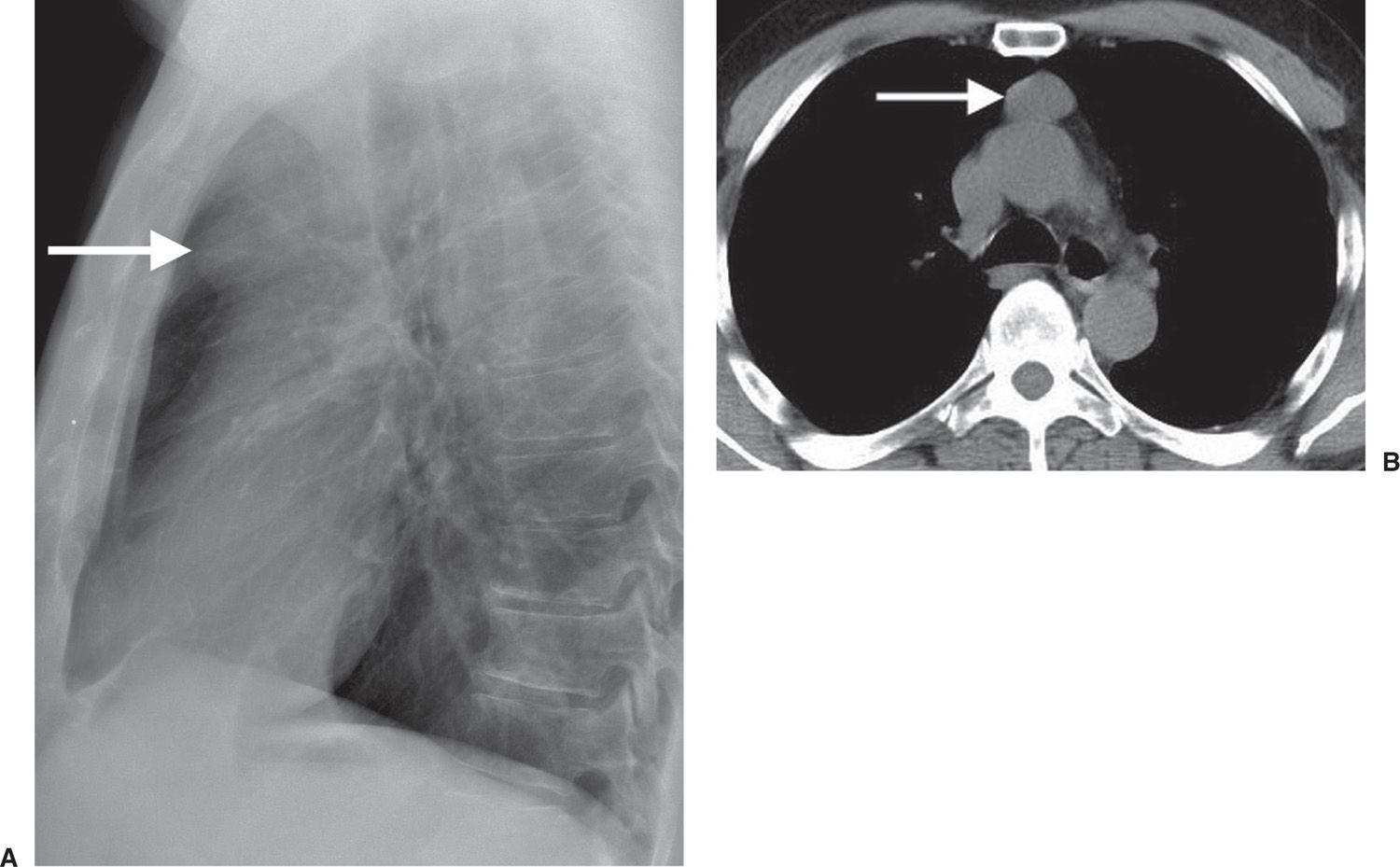

FIG. 6.11 • Benign thymoma. A: PA chest radiograph of a 70-year-old woman shows a rounded mass adjacent to the right heart border. The visualized margins are well-circumscribed (arrows). B: Lateral chest radiograph suggests that the mass is located in the anterior mediastinum (arrows). C: CT scan shows a peanut-shaped mass of fairly homogeneous attenuation (arrows). The mass is located anterior to the ascending aorta (A), above the right ventricular outflow tract, a typical location for thymomas.

FIG. 6.12 • Benign thymoma. A: Lateral chest radiograph of a 75-year-old man shows a rounded retrosternal mass (arrow), which was not visible on the PA view. B: CT scan shows a round circumscribed mass in the anterior mediastinum (arrow).

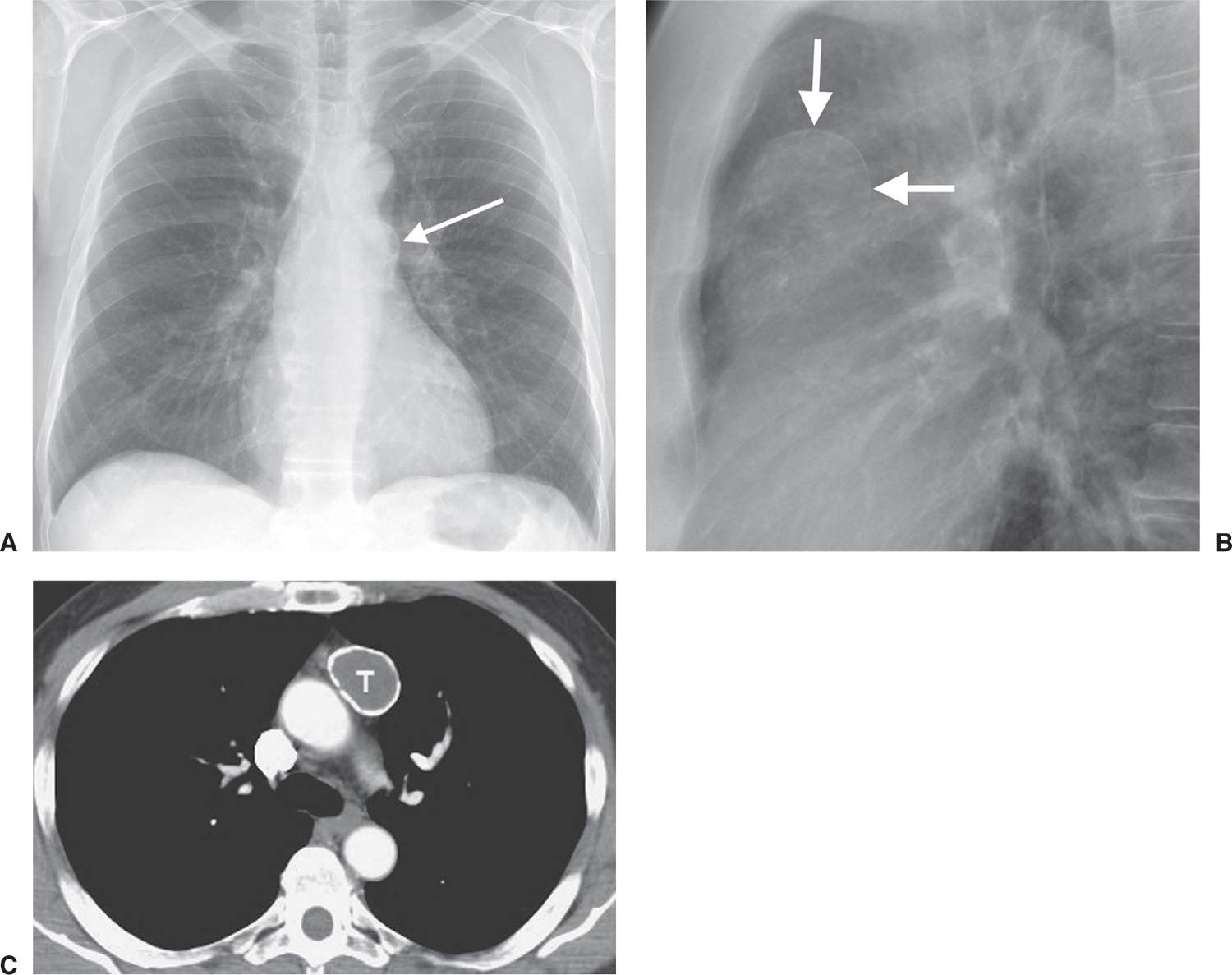

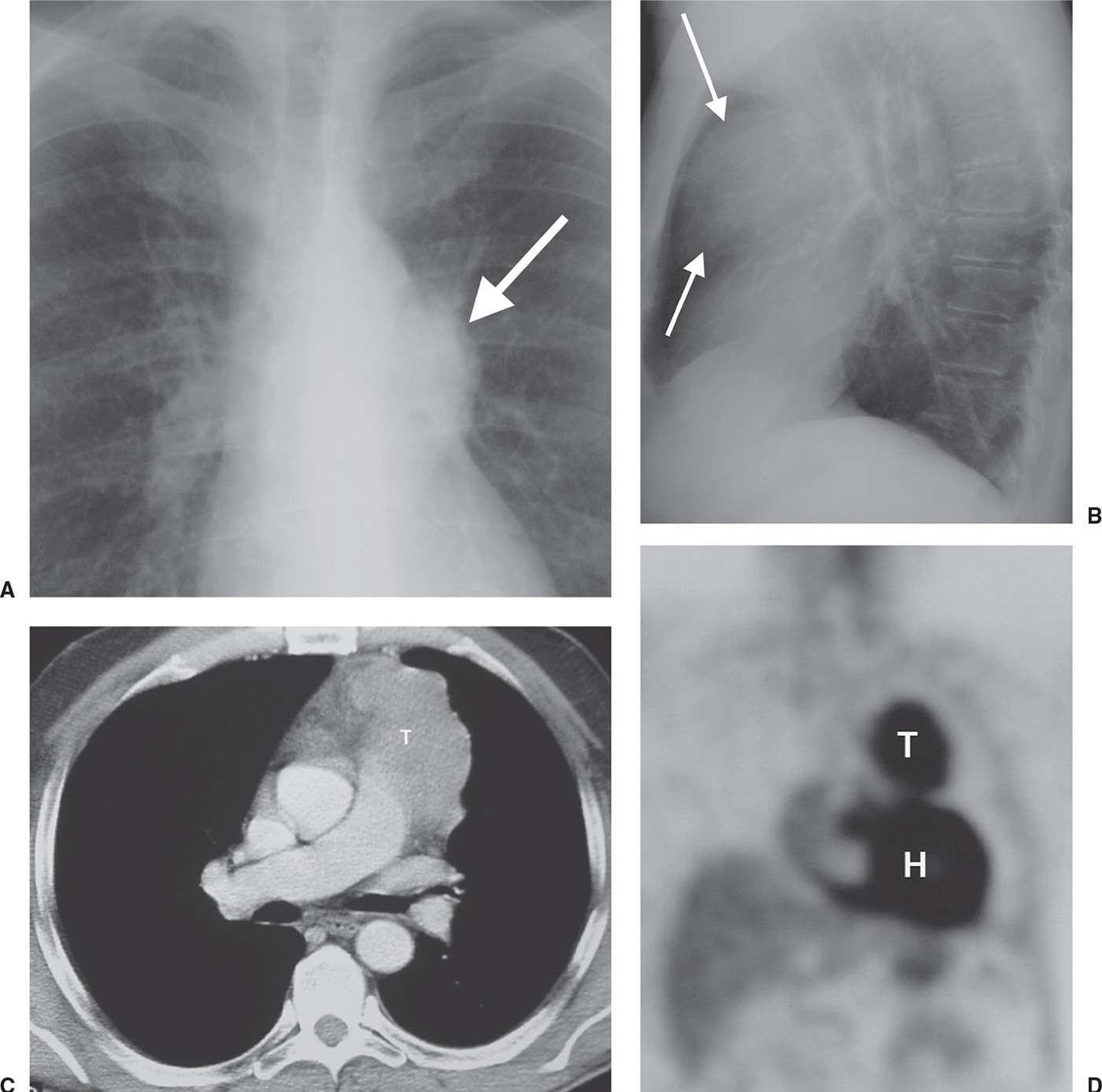

FIG. 6.13 • Benign cystic thymoma. A: PA chest radiograph shows an abnormal left mediastinal contour (arrow). B: Lateral view shows a round, circumscribed mass with a high-attenuation rim in the anterior mediastinum (arrows). C: CT scan shows a mass of soft tissue attenuation (T) with dense rim calcification anterior to the ascending aorta.

FIG. 6.14 • Malignant thymoma. Coronal (A) and sagittal (B) CT scans show a lobulated mass (arrows) of homogeneous soft tissue attenuation in the anterior mediastinum. C: Coronal CT with lung windowing shows a “drop” metastasis (arrow) along the left hemidiaphragm.

FIG. 6.15 • Malignant thymoma. A: CT scan shows a lobulated mass (T) of homogeneous soft tissue attenuation in the anterior mediastinum. B: CT scan at a level inferior to (A) shows course calcification (arrow) within the mass. C: A “drop” metastasis (arrow) is seen along the right hemidiaphragm.

FIG. 6.16 • Thymic cyst. CT scan of a 60-year-old man shows a circumscribed, rim-calcified oval mass of homogeneous fluid attenuation (C) in the expected location of the thymus gland.

FIG. 6.17 • Thymic carcinoma. A: PA chest radiograph shows an abnormal left mediastinal contour (arrow). B: Lateral view shows abnormal opacity in the retrosternal area (arrows). C: CT scan shows a lobulated mass of homogeneous soft tissue attenuation (T) in the anterior mediastinum. D: Coronal positron emission tomographic scan shows normal activity in the heart (H) and abnormal activity in the thymic mass (T).

Benign teratomas are found in patients of all ages but are most common in adolescents and young adults (Fig. 6.19). They usually produce a well-defined, rounded, or lobulated mass in the anterior mediastinum. They grow slowly, although rapid increase in size may occur as a result of hemorrhage, producing imaging features suggestive of a malignant mass. Calcification, ossification, teeth, or fat may be visible on a chest radiograph and on CT scans. CT scans may show cystic components and/or a fat–fluid level. A cyst wall with curvilinear calcification is often present. Unequivocal fat within the mass confirms the diagnosis of teratoma, but the absence of fat or calcium does not exclude a teratoma (Figs. 6.20 and (6.21).

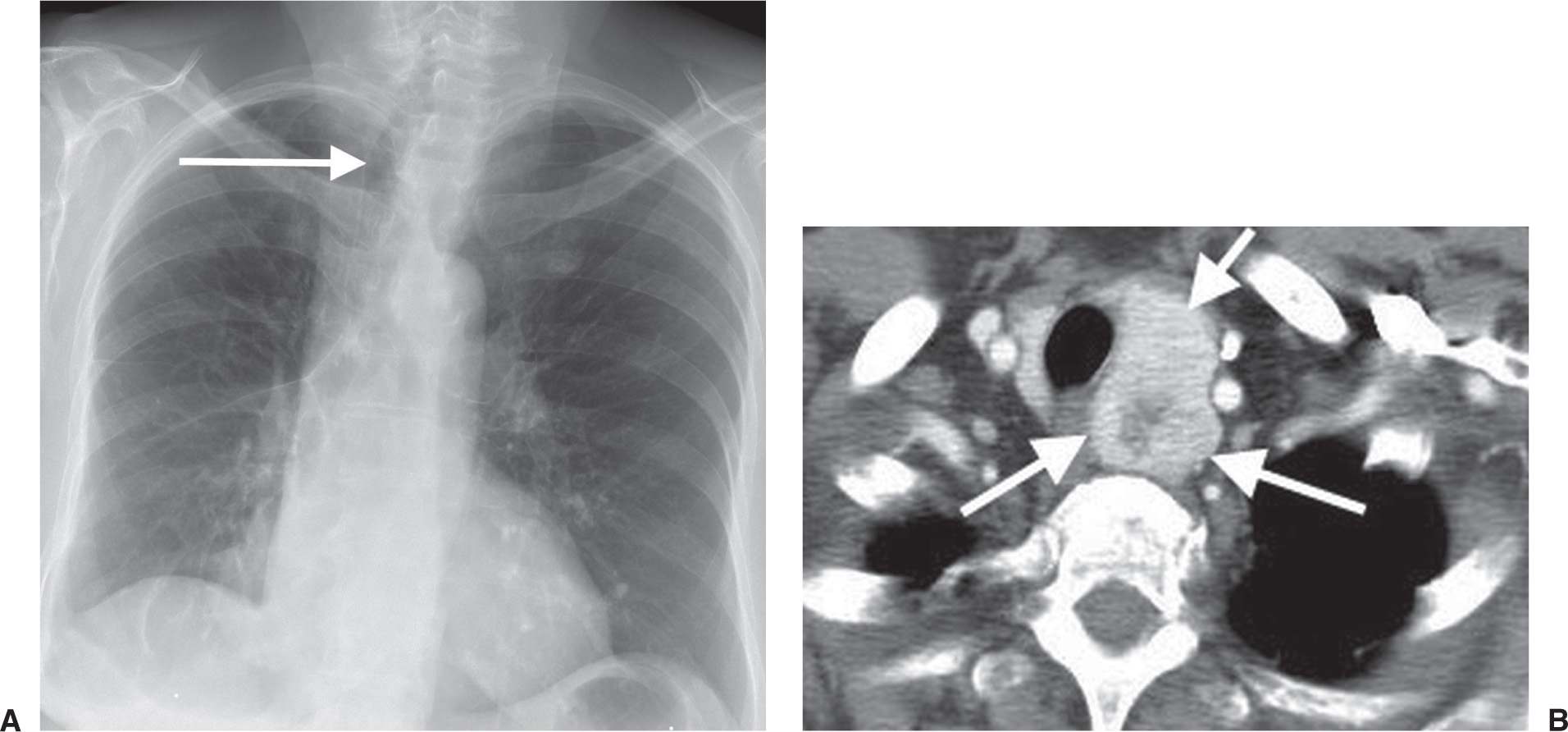

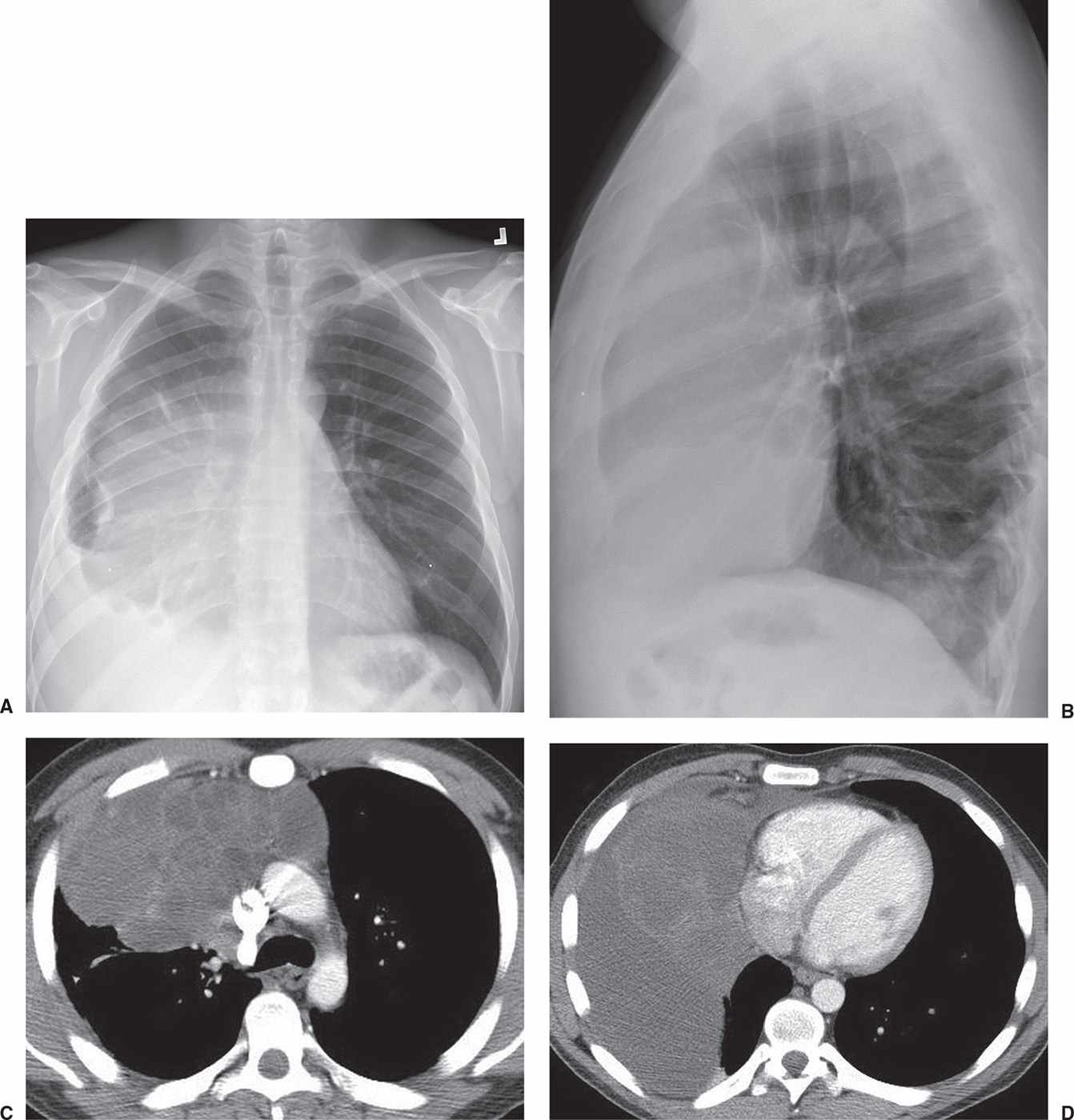

FIG. 6.18 • Yolk sac tumor. A: PA chest radiograph of a 26-year-old man with shortness of breath, cough, and a 30-pound weight loss shows a circumscribed mass obscuring the right heart border and a right pleural effusion. B: Lateral view shows abnormal retrosternal opacity. C: CT scan shows a mass with cystic components in the anterior mediastinum. D: CT scan at a level inferior to (C) shows the mass abutting the right heart and right pleural fluid.

Imaging features of malignant germ cell tumors are similar to those of benign teratoma except that fat density is not noted and calcification is rare. The malignant tumors grow rapidly, and metastases may be seen in the lungs, bones, or pleura. The adjacent mediastinal fat planes may be obliterated. The tumors may be of homogeneous attenuation or show areas of contrast enhancement interspersed with rounded areas of decreased attenuation from necrosis and hemorrhage. Rarely, coarse tumor calcification may be seen (9).

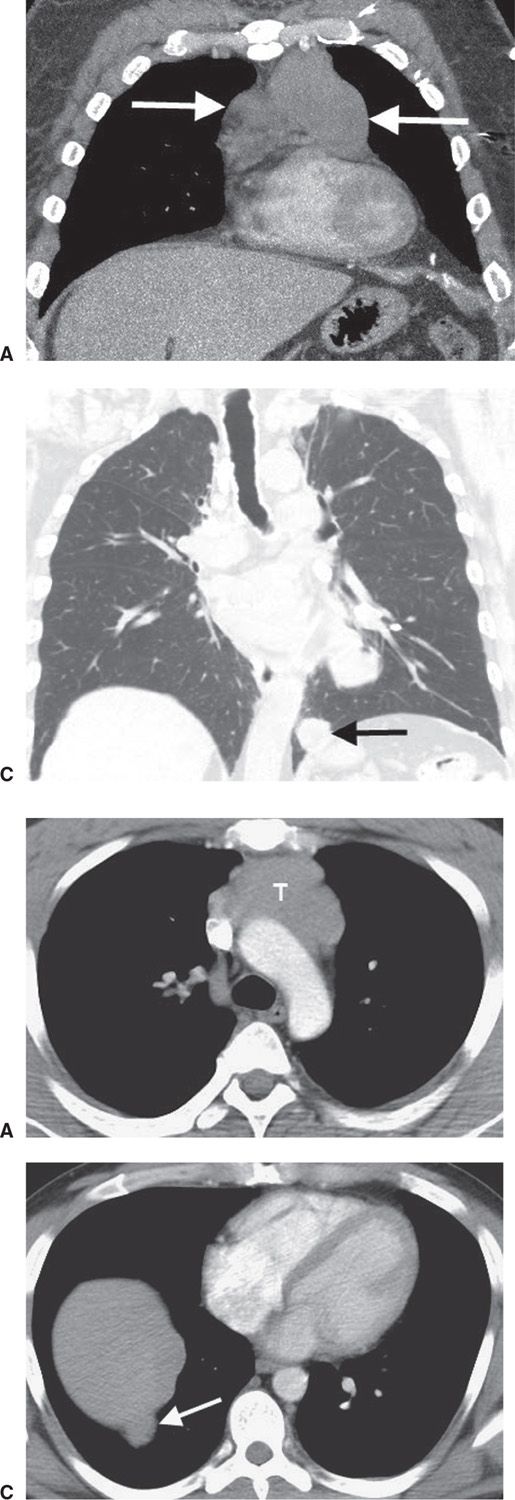

The fourth “T” can be remembered as terrible lymphoma or Thomas Hodgkin lymphoma. Thomas Hodgkin, an English physician considered one of the most prominent pathologists of his time and a pioneer in preventive medicine, is now best known for the first account of Hodgkin disease, a form of lymphoma and blood disease, in 1832. Lymphoma often extends beyond the anterior mediastinal compartment, involving a variety of lymph node chains, and is discussed along with middle mediastinal masses (see the following section). When lymphoma is isolated to the anterior mediastinum, the CT appearance can be similar to that of thymoma and germ cell neoplasms (Fig. 6.22).

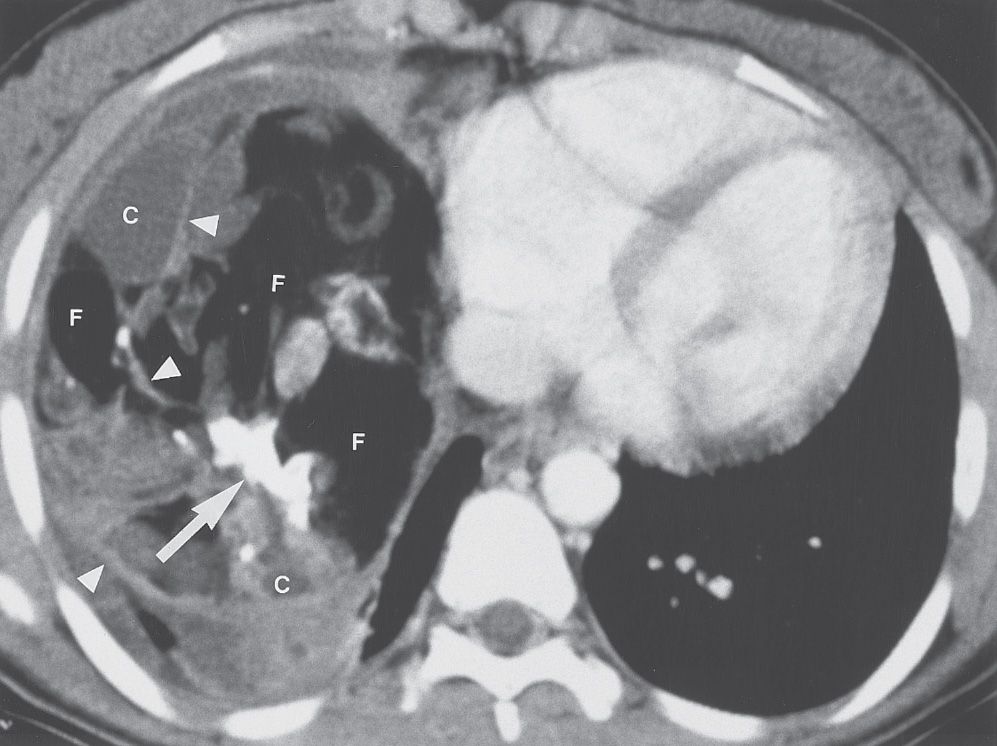

FIG. 6.19 • Benign teratoma. CT scan of a 16-year-old girl shows a large mass containing fat (F), cystic areas (C), and rudimentary “teeth” (arrow). Septations are present within the mass (arrowheads). At this windowing, fat appears similar in attenuation to air. Unequivocal fat within the mass confirms the diagnosis of teratoma. Note that large mediastinal masses can appear to fill an entire hemithorax.

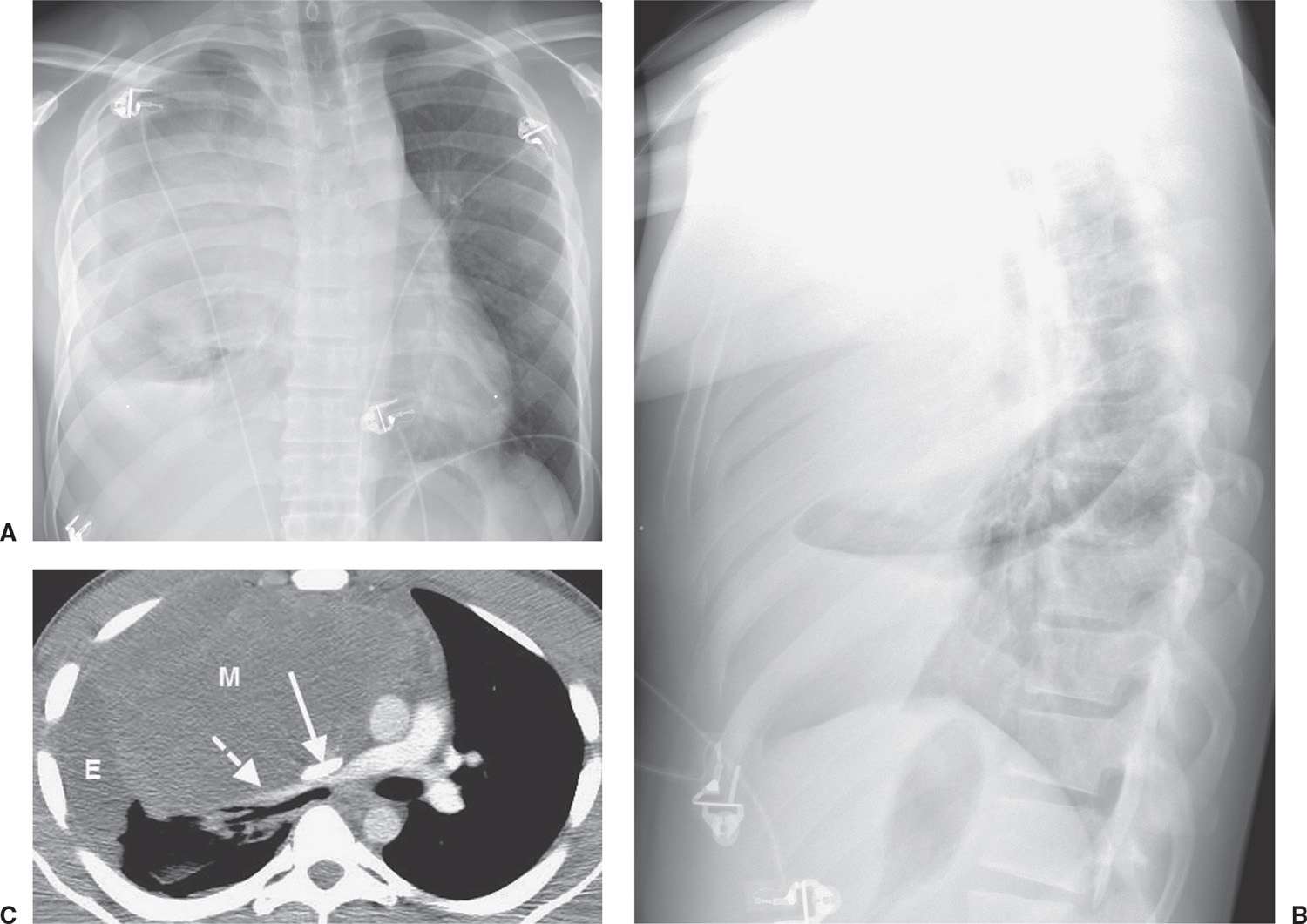

FIG. 6.20 • Benign teratoma. A: PA chest radiograph shows abnormal opacity in the right hemithorax, some of which is caused by pleural effusion, and mediastinal shift to the left. B: Lateral view shows abnormal opacity in the retrosternal area. C: CT scan shows an anterior mediastinal mass of homogeneous soft tissue attenuation (M), compressing a narrowed superior vena cava (solid arrow) and right pulmonary artery (dashed arrow), and right pleural effusion (E).

FIG. 6.21 • Benign teratoma. CT scan shows a round, circumscribed anterior mediastinal mass (arrow).

FIG. 6.22 • Lymphoma. CT scan of a 19-year-old man shows a heterogeneous anterior mediastinal mass (arrows).

MIDDLE MEDIASTINAL MASSES

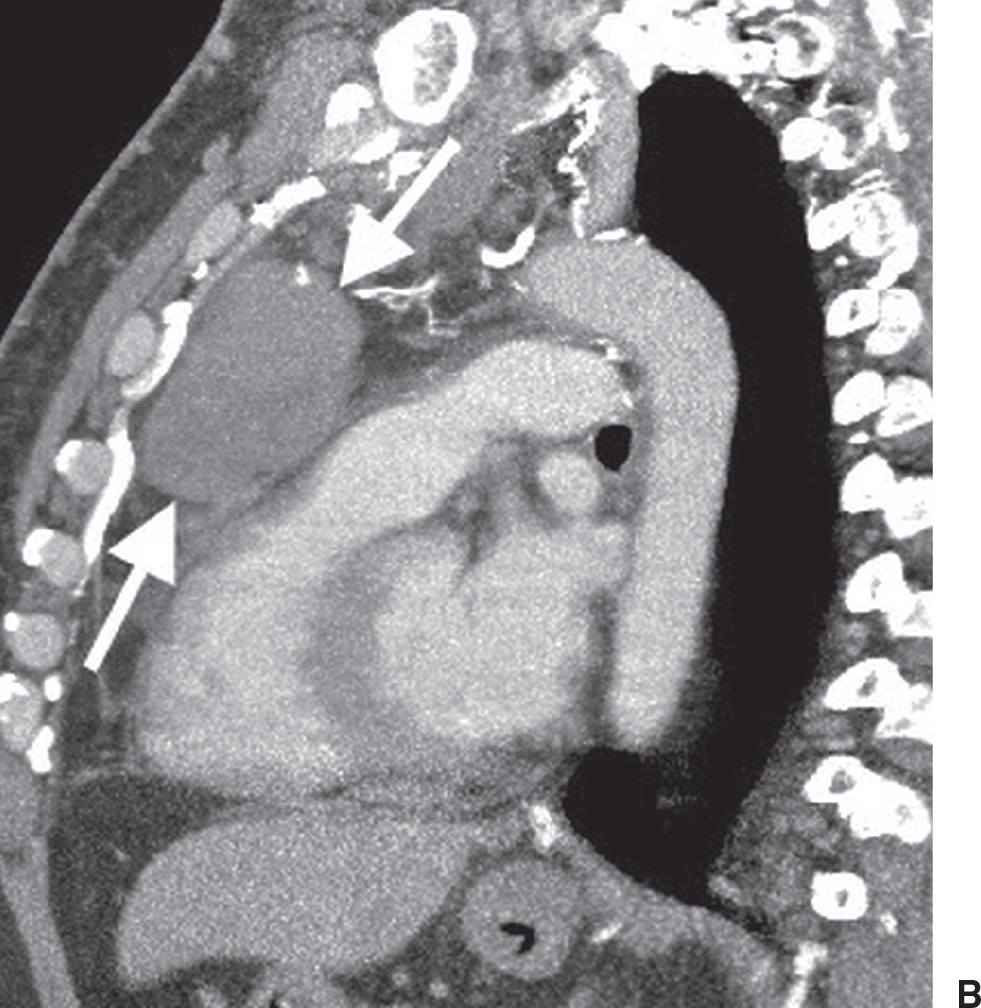

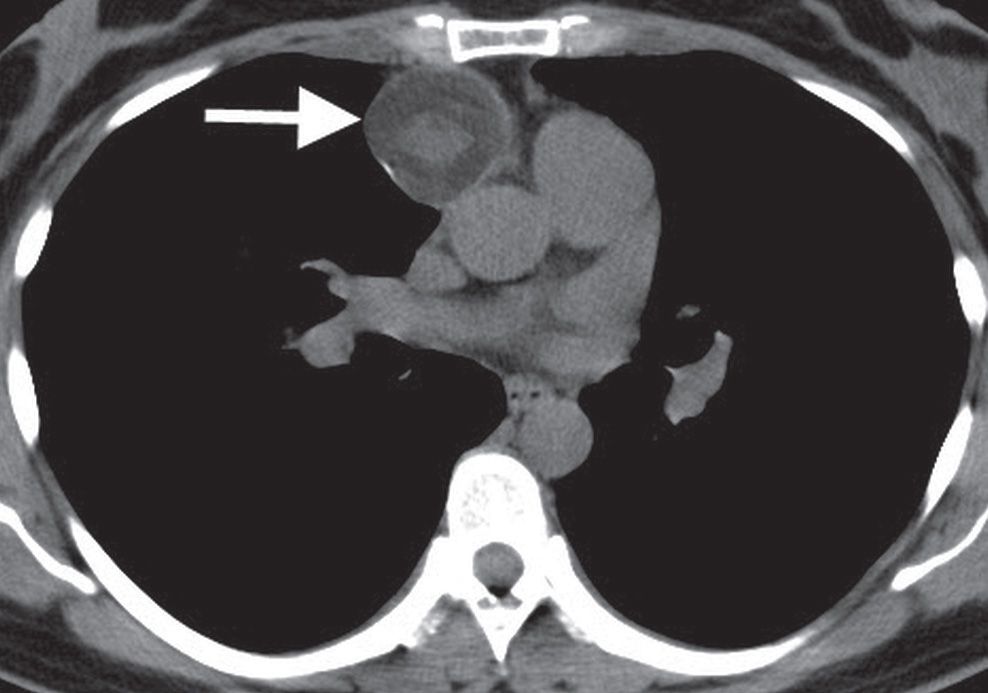

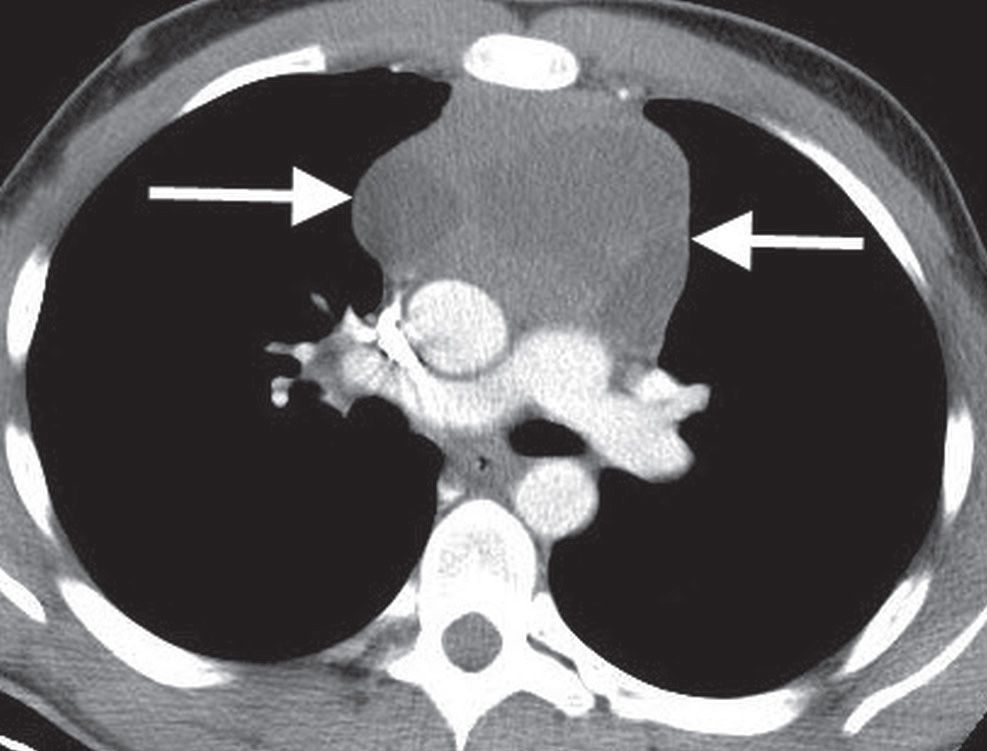

Also referred to as the vascular space, the middle mediastinum is bounded in front by the anterior mediastinum and posteriorly by the posterior mediastinum. The middle mediastinum contains the heart and pericardium, ascending and transverse aorta, superior vena cava and azygos vein that empties into it, phrenic nerves, upper vagus nerves, thoracic duct, trachea and its bifurcation, main bronchi, pulmonary artery and its two branches, pulmonary veins, and adjacent lymph nodes. The esophagus is variably described as a middle or posterior mediastinal structure. The main categories of abnormalities occurring in the middle mediastinum include adenopathy, aneurysm/vascular abnormalities, and abnormalities of development (Table 6.2). Less common middle mediastinal abnormalities include giant lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman disease; Fig. 6.23); neural tumor (involving the vagus or phrenic nerve); abscess; fibrosing mediastinitis; hiatal hernia (Fig. 6.24); primary tumors of the trachea or esophagus (namely, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, or carcinoma; (Figs. 6.25 to 6.28); and hematoma.

Table 6.2 MIDDLE MEDIASTINAL MASSES

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree