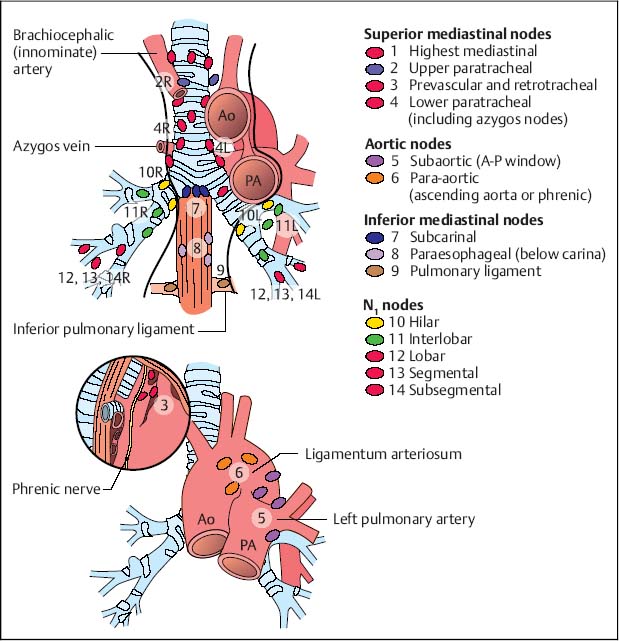

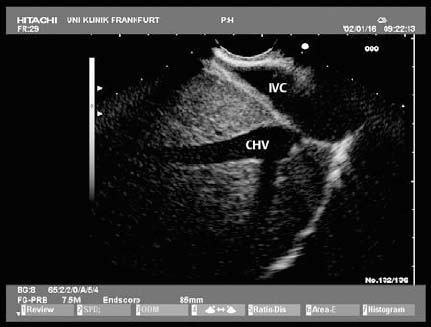

27 Mediastinum from the Esophagus Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) diagnostic techniques are extremely valuable in the mediastinum, but this has not yet been fully exploited in everyday clinical practice. It is not possible to evaluate the mediastinum adequately using only one method of examination; instead, a combination of endoscopic methods (e.g., bronchoscopy), radiographic methods (e.g., conventional techniques, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging), surgical methods (e.g., mediastinoscopy, thoracoscopy, thoracotomy), and ultrasound methods is necessary. Conventional radiography is undoubtedly important at the start of diagnostic work-up in the mediastinal region. The upper and anterior mediastinum can be seen adequately with transthoracic mediastinal ultrasonography, which is easily performed and also allows targeted aspiration of tumors to obtain histological confirmation of the suspected diagnosis.1–5 However, examination of the aortic lymph nodes and lymph-node groups in the lower and posterior mediastinum is not adequate with this method. Computed tomography (CT) allows the mediastinum to be examined accurately, but aspiration and collection of histological specimens from structures deep in the mediastinum require a separate procedure. Transesophageal endoscopic ultrasonography allows examination of the posterior mediastinum, as well as visualization and targeted aspiration of even the smallest structures in this area. On the other hand, the examination of pretracheal and paratracheal structures using endoscopic ultrasonography is not adequate (with the exception of the 2 L and 4 L nodes). Transbronchial endoscopic ultrasonography shows signs of being a promising method, but so far has only been used in a few centers and has not yet been fully evaluated. The diagnostic confirmation of mediastinal tumors and staging of bronchial carcinoma are therefore still dependent on mediastinoscopy, video-assisted thoracoscopy, and thoracotomy and mediastinotomy if necessary. Each of these methods only has a limited range of indications. Coordinating the application of the methods is even more difficult, since ultrasound techniques are not yet fully developed in the field of pneumology. Transesophageal EUS is often carried out by gastroenterologists, and interdisciplinary collaboration may be inadequate. A further disadvantage is that there is a relatively small number of pneumology centers in Europe in comparison with the USA, for example. The mediastinum is a complex space in which the lymph nodes of the upper mediastinum, the aortic lymph nodes, the lymph nodes of the lower mediastinum, and the pulmonary lymph nodes have to be distinguished. The pulmonary lymph nodes (hilar, interlobar, lobar, segmental, and subsegmental) are known as the N1 lymph nodes; the mediastinal and subcarinal lymph nodes as the N2 lymph nodes; and the supraclavicular and scalene lymph nodes as the N3 lymph nodes. The mediastinal lymph nodes are classified in accordance with the Mountain and Dresler system,6 which is adapted from an earlier classification by Tsuguo Naruke. The paratracheal lymph-node groups (level 2 L and 4L; L = left), the lymph-node groups in the aortopulmonary window (level 5), the subcarinal (level 7), and in particular the paraesophageal lymph nodes (level 8), can be viewed and punctured with real-time visualization. This is also possible in part for the lymph nodes in the region of the inferior pulmonary ligament (level 9). The same is true of metastases in the left adrenal gland, determining the prognosis in up to 5% of cases.7 Lymph-node levels 1,2 R, 3, and 4R (R = right), as well as 6, are not able to be assessed in most patients with normalsized lymph nodes, due to interference from the larger airways (Fig. 27.1). EUS imaging may be possible in patients with larger lymphomas. It has been shown that CT, which simply determines the size of mediastinal lymph nodes, is inadequate, with an accuracy level of 50-80%. The longitudinal position of the lymph nodes in the mediastinum is the critical factor, as this means that the lymph nodes can only be imaged from the side or at an angle. This is the reason for the notable inaccuracy of CT for determining the size of the lymph nodes. Endoscopic ultrasonography is able not only to assess the criteria relative to size, but also changes pertaining to the echo pattern, architecture, and localized infiltration. Fig. 27.1 Classification of the mediastinal lymph nodes according to Mountain and Dresler6. Radial and linear instruments are available for transesophageal endoscopic ultrasonography in the mediastinum, but the radial technique does not allow aspiration, and the longitudinal scanner is therefore preferable from the pneumological point of view. Aspiration specimens obtained with EUS can be assessed using either cytology or molecular biology. When enlarged lymph nodes are present, detection is also easier. When lymph nodes are detected, the lymph node (or an adrenal lesion) that is considered to be the most distant should be biopsied first, to avoid spreading malignant cells from local lymph nodes to more distant ones. Prerequisites. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) should be carried out before EUS in order to exclude stenosis and minimize the risk of perforation by the relatively inflexible EUS instrument. Extra care should be taken in inserting the instrument into the middle esophagus if a traction diverticulum is suspected and during passage through the gastroesophageal junction, where there is an increased risk of perforation due to aggressive forward movement. The explanation of the procedure given to the patient should be the same as for any endoscopic procedure in the upper gastrointestinal tract, with extra emphasis being given to the increased risk of perforation in comparison with conventional EGD. The patient should be informed about the risk of bleeding and infection (including potentially fatal progressive mediastinitis). The risk of bleeding is small when coagulation is adequate (Quick test > 50%, thrombocytes > 50/nL). Endoscopic ultrasound examination of the mediastinum can be performed as an outpatient procedure. After it has been explained to the patient, the examination requires 5-20 minutes, depending on the practitioner’s level of experience. It has proved helpful to work with a cytologist present during the examination, although this topic is a matter of controversy. Some authors have found that suction during fine-needle aspiration of lymph nodes increases the bloodiness of the specimen and does not necessarily increase the yield. The aspiration procedure is described elsewhere (see Chapter 10). Fig. 27.2 The diaphragm, with the confluence of the hepatic veins (CHV) at the inferior vena cava (IVC). Sedation. Sufficient sedation is extremely important. EUS-guided aspiration should only be carried out with adequate sedation, without cough stimulation or patient movement, as accidental puncture of the heart or large mediastinal vessels has to be avoided. Anesthesia that can be easily controlled is therefore necessary. In our experience, propofol (Diprivan) is more suitable than midazolam for this purpose, but comparative studies on this topic are lacking. The instrument is guided into the esophagus with endoscopic visualization. From the upper esophagus (18-20 cm past the incisor line), insertion can continue using either endoscopic or endoscopic ultrasound viewing. Although orientation may be possible using the surrounding structures while the scope is being inserted, systematic examination starts distally, as control is much better when the scope is withdrawn. When the scope is rotated, the tracheal and bronchial airways ventrally, the echo-free vessels mainly laterally, and the hyperechoic bone structures dorsally can all be used as simple landmarks for orientation. The systematic examination of the mediastinum starts distally, with the instrument in the cardiac region at the level of the thoracoabdominal junction. In this position, one can identify the liver, hepatic veins, inferior vena cava, heart chambers and heart valves, the left and right ventricular outflow ducts, the ascending aorta, the pulmonary trunk with the pulmonary arteries, and the aortic arch with the aorticopulmonary window. When the endoscope is turned and one orients oneself along the reflexogenic spine, it becomes possible to identify the descending aorta paravertebrally on the left and the azygos vein on the right. Further up, the vessels emerging from the aorta, particularly the cervical vessels (the common carotid artery and jugular vein), the thyroid, and the paratracheal lymphnode groups can be observed from the tracheal bifurcation up to the mouth of the esophagus. The pretracheal lymph nodes are beyond the range of EUS, as they are concealed behind the air-filled trachea. The pneumological examination using EUS is completed by imaging the left adrenal gland and if possible the right adrenal gland (see Chapter 21) and by examining the lymph nodes of the celiac trunk. One can also start assessing the more distally located structures here, with the transduodenal and transgastric part of the examination taking place to begin with. The mediastinal lymph-node groups are examined using the following markers: the echo-free heart chambers and vascular paths; the ventral hyperechoic (air-filled) tracheobronchial system; and the dorsal echogenic bone structures of the spine. Directly next to the esophagus are the periesophageal and paravertebral lymph-node groups. The paracardiac lymph nodes can be found in the immediate neighborhood of the heart. Along the contour of the heart on the upper side of the atrium, the subcarinal lymph nodes can be detected in the tracheobronchial region, and the lymph nodes of the pulmonary ligament are located somewhat further distally. Fig. 27.3 The pericardial cavity (PC) with the left lobe of the liver (L) and tip of the heart (H). The course of a typical examination is described in Chapter 2. Figures 27.2, 27.3, 27.4, 27.5, 27.6, 27.7, 27.8, 27.9, 27.10, 27.11, and 27.12 focus on the anatomy of the mediastinal vessels using color Doppler imaging and miniprobe ultrasonography of the mediastinum, and showing potential artifacts.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

General

General

Procedure

Procedure