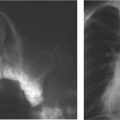

Right aortic arch (also with aberrant left subclavian artery); sometimes caused by asymmetric double aortic arch

Fig. 1.137 |

Tracheal impression on the right, deviated to the left, above the bifurcation at the level of the left aortic arch. CXR: Trachea deviated to left at level of arch and narrowed. Associated oesophageal narrowing. CT/MRI and/or echocardiogram: definitive evaluation. |

Vascular ring more common with right arch with aberrant left subclavian than with right arch and mirror image branching. Ductus may be patent or merely a ligamentous remnant (see Table 1.49 ). |

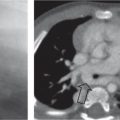

Double aortic arch

Fig. 1.138

Fig. 1.139a, b |

Chest X-ray (CXR): Narrowing of trachea at level of double arch. The right arch is usually dominant, and radiographic appearance may simulate a right arch (i.e., trachea deviates to left). Obstructive overinflation frequent. Associated esophageal narrowing.

CT/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or echocardiogram: definitive evaluation. Bilateral tracheal and esophageal impression above the bifurcation. Impression is ventral on the lateral view (dorsal impressions of the esophagus). MRI. |

A segment of either arch may be atretic: this can make distinction from other vascular rings challenging. For example, a double arch with atresia of the distal left arch may be very similar in appearance to a right arch with mirror image branching (see Table 1.87 ). |

Left brachiocephalic and common carotid artery (left innominate artery; “innominate artery compression syndrome”)

Fig. 1.129, p. 74 |

Defined by >50% narrowing of trachea at level of innominate artery. The innominate artery may be anatomically normal, be dilated or aneurysmal, or have a distal origin from the arch with an abnormally horizontal course of innominate artery across trachea. Ventral tracheal compression just below the level of the clavicle. |

A controversial entity: In many cases, the primary abnormality is tracheomalacia, which allows the innominate artery to take the apparently abnormal course. Mild narrowing of the airway at the level of the innominate artery is a normal finding in many infants. Aortopexy may be beneficial in some symptomatic cases, however (see Table 1.87 ). |

Aberrant left pulmonary artery (“pulmonary sling”)

Fig. 1.134, p. 76 |

CXR: The lower trachea is displaced to the left. The carina is often widely splayed and may appear almost horizontal. There may be overinflation, more commonly of the right lung, due to main bronchial compression.

CT/MRI: left pulmonary artery arises anomalously from distal pulmonary trunk or right pulmonary artery, and runs between trachea and esophagus. |

There is frequently (~50%) associated long-segment congenital tracheal stenosis and an abnormal tracheal branching pattern. Also associated with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), atrial septal defect (ASD), tetralogy of Fallot, and persistent left-sided superior vena cava. |

Tracheal foreign body aspiration |

Mimics a stenosis, especially if radiolucent. Mobile foreign bodies can occur. Normal findings on radiography are common.

Endoscopy. Fluoroscopy may show asymmetric diaphragmatic motion. |

Acute onset. Stridor, especially in young children (“virtual vacuum cleaners”). Localization hint: coins project en face in the esophagus, only laterally as trachea too narrow. |

Swallowed foreign bodies (radiopaque or radiolucent)

Fig. 1.140 |

Impacted foreign bodies may compress the trachea dorsally (secondary to edema). |

Acute onset of stridor or mild respiratory symptoms in small children. Difficulty in swallowing. |

Stenosis after surgical repair of esophageal atresia, compression by the dilated proximal esophagus |

Findings resemble those of left-sided brachiocephalic trunk. Stenosis at the height of the anastomosis. UGI with caution. |

Typically barking cough, stridor caused by localized tracheomalacia. |

Postintubation, tracheostomy, and surgery

Fig. 1.141 |

|

Usually caused by too large a tube, resulting in pressure ischemia of respiratory mucosa. Accounts for 90% of mature acquired laryngotracheal stenoses. Develops in 1%–5% of patients undergoing prolonged endotracheal intubation. Postesophageal atresia, late sequelae of mucosal granulomas, scarring, or strictures. Stridor following extubation may require reintubation. |

Masses—extramural: paratracheal or bronchogenic cysts, goiter, lymph-adenopathy, lymphoma, and localized retropharyngeal abscess

Fig. 1.142a–c |

Tracheal lumen narrowed at the level of the lesion. US, CT, MRI are most useful. Variable a ppearance according to lesion. |

Respiratory symptoms vary with the mass size: stridor, gasping, labored breathing, chronic recurrent infections. Need for endoscopy usually based on clinical findings. Common lesions include lymphoma, bronchogenic cyst, esophageal duplication cyst, neuroenteric cyst, mediastinal teratoma, lymphadenopathy, thyroid lesions, thymic lesions, lymphatic malformation, and hemangioma. |

Masses—intramural: hemangioma, polypoid hemangioendothelioma, lymphangioma, cysts, ectopic goiter (subglottic)

Fig. 1.143 |

Endoscopy; CXR, CT, MRI. Soft-tissue density may be visible on CXR. There may be generalized air trapping. |

Rare: more common causes include subglottic hemangioma, Wegener granulomatosis, and laryngotracheal papillomatosis. |

Segmental tracheal stenosis, segmental tracheomalacia |

Seldom an isolated lesion, more commonly in combination with tracheoesophageal fistula or after surgical repair of esophageal atresia, at the site of the anastomosis and fistula repair. |

|

Traumatic |

|

Occasionally occurs following blunt trauma to larynx and trachea. Also occasionally following caustic ingestion and inhalational and thermal injuries. |

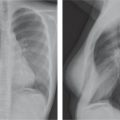

Congenital tracheal stenosis

Fig. 1.144a, b |

May be short-segment, long-segment, or even extend into the main bronchi. Often features complete cartilaginous rings, producing an abnormally rounded appearance of the airway on cross-section. Diagnosis usually made at endoscopy ± contrast bronchography. Echocardiography and CT performed to identify extrinsic compression. |

Up to 1% of all laryngotracheal stenoses. Frequently associated with cardiac defects, particularly pulmonary artery sling. Also associated with pulmonary agenesis and aplasia. |