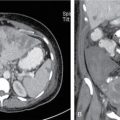

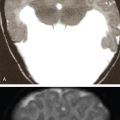

Mohanan Ethics is knowing the difference between what you have a right to do and what is right to do. Potter Stewart In this chapter, we will review the basic principles outlined by Beauchamp and Childress that provide a sound ethical basis for clinical decision-making. We will explore the application of these principles and additional principles of medical ethics across the clinical, interventional and research spectrum of services that radiology provides. An understanding of these principles and their application across the spectrum of radiology services is expected to lead to the delivery of services that contribute towards an appropriate level of protection for people who receive and provide the service, and the environment in which they function and sustain, without unreasonably limiting the desirable human actions and benefits that occur as a result of radiology services. The world is rapidly shrinking to a “global village” with easier access and integration with different cultures. Radiology is global in its clinical application, research, infrastructure and regulatory framework. There is a need to develop approaches to decision-making that are acceptable for people, physicians and patients, from different cultural backgrounds. Patients are able to travel and access care in different settings and in different countries. Doctors have to provide counsel to patients and peers from radically different cultures in different cultural contexts. A common framework of ethical decision-making built upon strong cross-cultural foundations is necessary for the practice of medicine into the future. At the end of this chapter, you should be able to The practice of medicine has historically been associated with values that offer care and protection to beneficiaries and are aimed at minimizing unintended harm to people. The Hippocratic oath provides a framework for care, empathy and ethical sensitivity in the way patients are treated and therapy is delivered. Decision-making in medical sciences is influenced by several factors. The most important factors include The approach to ethical decision-making in clinical medicine, although present since historical times, was framed into a formal structure by Beauchamp and Childress in 1979. These principles still retain a great deal of acceptance within the broader medical community primarily because they transcend cultural and individual differences and are rooted in “common morality.” The principles formulated by Beauchamp and Childress can be applied across cultures and different settings without being limited by culture specific contexts. They are of sufficient generality and flexibility to be widely applied to all medical disciplines including radiology. Respect for autonomy is a value to ensure that the person receiving care or the patient is the main decision-maker in his or her own case. The consideration of the individual’s point of view is part of medical professional ethics all over the world although its application may vary by cultural contexts. The principle of respect for autonomy suggests, with specific regard to radiology, that wherever possible, the provision of a radiology service has to take account of the individual’s agreement and this is a prerequisite for justification of the service provided. Beneficence means promoting or doing good, and non-maleficence means avoiding causation of harm. These two ethical values are interrelated and hence are presented together. Both beneficence and non-maleficence are enshrined in the Hippocratic oath that demands that a physician do good and/or not harm. They were formalized in modern biomedical ethics in the late 1970s through the Belmont Report and further consolidated as an integral set of principles or values by Beauchamp and Childress. In its most general meaning, beneficence includes non-maleficence although beneficence and non-maleficence can also be seen as two separate values. We consider them as two interrelated parts of the same coin and hence will consider them together in this chapter. Non-maleficence is closely related to prevention and aims to limit risk by eliminating or reducing the likelihood of hazards, injuries and complications and thus promote well-being. Beneficence also includes direct benefits for individuals, communities and the environment. Radiology practices that seek to protect people against the harmful effects of radiation. Practices in radiology also contribute to the best interest of individuals and thereby their quality of social life. This may be achieved by avoiding and minimizing deterministic effects and stochastic effects as far as possible in a particular set of circumstances or in a particular environment. The deliberate use of radiation and radiology practices can be associated with certain risks, but has several desirable consequences, such as the improvement of diagnostics or therapy in medicine, or quality of life of the patient and of society in general. These have to be weighed against the potential harmful consequences. A key challenge for beneficence and non-maleficence is the methods of ascertaining the benefits, harms and risks. In radiological protection, this involves consideration of both their individual and societal aspects and these have to be viewed in alignment with other medical, demographic, social, psychological and cultural factors that can influence outcomes and the risk–benefit analysis. An evaluation of beneficence and non-maleficence must also consider who or what is included and excluded in the evaluation of potential harms and benefits. These must include effects on future generations (Fetal Radiology is a good example in this regard) and the environment. Environmental harm may be considered within the framework of harm avoided for the sake of people (an anthropocentric view), or protection of the environment for its own sake (a non-anthropocentric approach). Both these approaches are compatible with the value of beneficence and non-maleficence. The principle of justice is a globally acceptable foundation of ethics. Justice can be described as fairness to all persons equally. When we say equally, it indicates an equal probability or distribution of the advantages and disadvantages to all populations or subsets of populations served. Justice can be Inequity is inevitable when benefits and consequences are not equally distributed among populations. With specific regards to radiology, justice indicates that every person who fulfils a given set of clinical criteria have an equal probability of receiving the test in question. Justice also indicates that radiation protection is equally offered to all populations and consider dose constraints, reference levels, and derived consideration reference levels. Exposures should not exceed the values beyond which the associated risk is considered as intolerable or hazardous given a particular situation and are defined by the use of dose limits. Justice also has an intergenerational context, with the principles of justice considering the effect on future generations as well. Ethics in radiology also utilizes a set of pragmatic values and principles that overlap with the four basic principles of medical ethics outlined by Beauchamp and Childress. These principles include Prudence can be described as the making of informed and carefully considered choices in the absence of full knowledge of the consequences of an action as part of the services provided. Prudence, which also means practical wisdom, indicates the quality of having knowledge, experience and good judgement to take reasonable decisions and to act accordingly. Prudence is a long-standing principle in medical ethics and philosophy from ancient times and, in medical practice, indicates a pragmatic acceptance of the uncertainties or limitations of medical knowledge at any given point of time. Radiology, as is most medical disciplines, is evidence based. However, any evidence base also includes a level of uncertainty that is built into the evidence. These may include uncertainty about consequences at certain exposure doses or dose limits, or effects of interventions or therapies. Prudence also encompasses how decisions are made, and are not limited solely to the outcome of those decisions. Clinical decision-making requires prudence as a central value integrated with evidence. Prudence is sometimes phrased as the precautionary principle that affirms that a lack of scientific certainty should not be used to postpone or delay or avoid appropriate measures where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage. Prudence and the precautionary principle, however, are not to be confused with the lack of risk taking in medicine or the avoidance of any risk. They do not indicate using a zero-risk approach, or suggest always choosing the least risky option or to take action just for the sake of doing some action. Dignity implies that every person deserves unconditional respect and has the capacity to make informed decisions of their will. Respect for human dignity is more often than not encompassed by the use of informed consent that means a person has the right to accept a risk voluntarily and the right to refuse to accept. Informed consent is also linked with the concept of “right to know” that makes the choices really “informed” in nature. Issues surrounding radiation protection have been recognized since 1928 when the first international recommendations on radiological protection were developed by the International X-ray and Radium Protection Committee (IXRPC). The 1928 Recommendations had a predominant focus on “X-ray and radium workers” in medical facilities, and provided advice meant to avoid harmful skin reactions and derangements of internal organs and changes in the blood. This advice was based on the best scientific knowledge at the time and the relatively simple, implicit ethical principle of “doing no harm.” The prevalent thinking of the time was that straightforward protection measures could keep exposures low enough to avoid injury entirely. The only type of effects known at that time were deterministic effects, which are considered to have a threshold below which no deleterious effects are seen. Knowledge and awareness of radiation protection continued to increase over the next 2 decades with the concept of a tolerance dose introduced in the 1934 congress of the IXRPC. The 1950s saw a growing societal concern about the effects of exposure to radiation to the public, patients and those working in radiation environments. These societal concerns were fuelled by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 and the nuclear weapons testing after World War II causing global contamination. Radiation use was increasing in many fields including the nuclear energy industry, potential hereditary effects were now increasingly recognized through animal experiments, and evidence of increased leukaemia in radiologists and atomic bomb survivors started to appear. The 1954 Recommendations (ICRP, 1955) officially recognized that radiation levels higher than the natural background can no longer be regarded as absolutely “safe” and recommended that “exposure to radiation be kept at the lowest practicable level in all cases”. The increasing recognition of cancer and hereditary effects or stochastic effects saw a paradigm shift from avoiding harm to managing the probability of harm. Ethics evolved around radiation protection to a point where ICRP, in 1977, described the primary aim as “protection of individuals, their progeny, and mankind as a whole while still allowing necessary activities from which radiation exposure might result”. This resulted in protection being constrained to avoid interfering with necessary activities. The introduction of the three basic principles of radiological protection that included justification of practice, optimization of protection and limitation of individual doses, occurred in 1977. This was the first attempt to introduce considerations about tolerability of risk to derive individual dose restrictions. In 1991, ethical considerations evolved to focus more on balancing benefits of protection from radiation and the benefits of the use of radiation rather than focussing primarily on constraining protection. Environmental awareness and societal awareness around environmental concerns increased over the next 2 decades with an elaboration and explicit reflection on ethical values that were inclusive of the different philosophical world views regarding how the environment is valued through anthropocentric, biocentric and ecocentric approaches. Discussions expanded to address procedural principles and operational strategies, including the precautionary principle, informed consent, and stakeholder participation. Fundamental Principles of Radiation Protection Effective integration and implementation of the fundamental ethical foundations of radiation protection necessitates a set of common procedural values. These include The core ethical values integrated with the three overarching principles of justification, optimization and limitation help people take ethical decisions while still acknowledging the uncertainties associated with the effects of low dose and practice, and to evaluate the adequacy of these actions. Pragmatically, reasonable levels of protection (the principle of optimization) and tolerable exposure levels (the principle of limitation) are ongoing and evolving pursuits that depend on several advancements and factors including the desire to do more good than harm (beneficence/non-maleficence), to avoid unnecessary exposure (prudence), to seek fair distribution of exposure (justice) and to treat people with respect (dignity). Radiology is a rapidly evolving field with newer innovations in instrumentation, techniques, image acquisition, image analysis and consequently, rapidly evolving skill sets and interpretative algorithms as well. These advances are exciting for the practising radiologist and for the referring clinicians who see a greater window of opportunity to visualize images and make better clinical decisions. However, it is important to consider if the improved diagnostic abilities and use has actually translated to improved health outcomes, from a functional perspective, from an individual perspective and from a societal perspective. Is the increased utilization of radiology services translating to better clinical outcomes? Overuse in radiology may be literally translated as the increased use of a service, action or imaging application where they are unlikely to lead or do not lead to an improved clinical outcome. There are several factors that influence overuse in radiology. An understanding of these factors, not all of which are in the control of the radiologist, gives a perspective of ethical issues that arise in relation to overuse. Some factors that influence over use of Radiology Services The clinical practice patterns of radiologists and referring physicians is an important factor in the determination of use and over use of diagnostic radiology. Practice patterns are not usually in isolation but are interlinked with several clinical and non-clinical factors. These include the training and educational support received for upgrading skills consonant with newer advances, availability of follow-up educational services, affordability of training programmes and the ability to take time off for training programs especially when they are offline. Online training modules are increasingly utilized to address some of these factors but are also limited by technical issues including the strength and reach of the internet network. The influence of peer pressure and the societal/financial pressure to be seen as on the cutting edge of service provision is a factor that should not be discounted in clinical practice. Self-referral has to be viewed from two perspectives. From the perspective of a medical practitioner, self-referral can occur when a non-imaging medical specialist or a non-physician refers subjects to his or her own imaging facility and when physicians refer patients to an outside facility where they have a financial stake. From the perspective of a patient, self-referral is not uncommon with patients often referring themselves for particular tests based on information obtained from non-medical sources or medical sources on the Internet. Self-referral is also increasing as part of “seeking a second opinion” where patients often check if a particular opinion provided is “correct.” Defensive medicine is considered as diagnostic or therapeutic actions done as a safety measure against potential claims of malpractice rather than to provide any particular benefit to the patients through the clinical management process. Increased litigation has led to more testing to avoid missing any finding, however inconsequential it may be, leading to an increase in defensive medicine. The over use of testing may lead to the detection of findings that are not clinically important and lead to further testing to rule out impact of the additional findings detected. Duplicate testing and inappropriate requests for tests are linked with training, clinical practice patterns, self-referral and defensive medicine. Additionally, these are also linked to the practice of providing patients with copies of their imaging studies, and the compliance of the patient to store, preserve these images and carry them for the next assessment. Imaging studies are often duplicated when results of previous exams are unavailable, insufficient or not considered relevant to the clinical condition. Nearly 30% of healthcare spending is found to be duplicative, unhelpful or even making patients worse. The risk of over imaging and over diagnosis is particularly important in clinical areas where the “a priori” risk related to radiation exposure and consequent effects is high as in oncology imaging or emergency services. The use of computed tomography and MRI has increased fourfold in the last decade for several clinical condition such as trauma, pulmonary infections, abdominal pain and pulmonary embolism. The indiscriminate use of computed tomography can lead to an increase in incidental random findings and further lead to a costly and potentially harmful diagnostic, therapeutic or interventional cascade of processes that may be costly but not necessarily beneficial. These practices that lead to over use and over diagnosis lead to conflict with several of the ethical foundations of radiation protection and radiology practice. The overuse of medical imaging has resulted in unsustainable costs across the healthcare systems besides exposing both single individuals and general population to unnecessary radiation doses. We also need to consider that resources for health services are finite and not equitably distributed and it is unethical to provide expensive non-essential health services to one sector of the society when another sector lacks or does not receive even basic essential services. The major ethical problems in radiology emerge in the process of justification or reasoning for the use of medical exposures of patients in a clinical situation. The medical exposure of patients is intentional as a planned test and one expects a consequential expectation for a direct health benefit to the individual. The final responsibility for justification of a particular procedure lies with the relevant physician, who should be aware of risks and benefits of the involved procedures. The principles of informed consent, right to know and transparency are helpful to improve ethical decision-making. However, these have to be rooted in a true voluntary value that is not often possible in paternalistic cultures. Ethical issues are usually interlinked and not seen in isolation. We can see issues of beneficence and non-maleficence, issues of patient autonomy, distributive justice, prudence, dignity, honesty and trust that are interspersed with these practices. The practices also have an add-on effect with physicians down the line of management forced to add on tests based on prior reports that maybe inappropriate. In clinical practice, the choice of a modality is an ongoing effort based on science, evidence, experience and evaluation of outcomes, interspersed with values and ethics. At an individual practitioner level, this involves documenting and evaluating outcomes, sharing of clinical knowledge with peers and communication of risks and benefits to patients. Interventional radiology is a relatively new field in the discipline of radiology. It is an exciting field with several nuances for interventions previously considered not possible that can impact positively on the sustenance and quality of life. Interventional radiology is evolving rapidly, driving innovations in therapeutic and diagnostic approaches. However, one has to consider that, as a rapidly evolving field, the base of evidence for clinical decision-making is also in the evolutionary phase with a need for more evaluation, consolidation and application. Any interventional discipline opens itself up to the possibility of errors and complications occurring as a result of the intervention itself and the decision-making that precedes and succeeds the intervention. We can consider errors to indicate that a mistake was made while a complication implies that something went wrong even when everything was done according to the book. This fine splitting is useful from an operational or process perspective but are not much use at an individual or ethical level. Charles Bosk, in his seminal work on failures and complications in the medical culture, described four types of errors. Technical, judgement and quasi-normative errors may occur in a rapidly evolving field and can be forgiven as long as they are not repeated on a regular basis. However, one has to remember that not all errors or complications are driven solely by a medical process. Errors can also occur as a result of insufficient patient compliance, the inherent unpredictability of the progress of disease, non-compliance by non-medical staff and equipment (hardware or software) malfunction. Classification of medical errors by Bosk

1.29: Medical ethics: Principles and application in radiology

Learning objectives

Principles of medical ethics

Respect for autonomy

Beneficence and non-maleficence

Justice

Additional ethical values or principles in radiology

Prudence

Dignity

Ethical principles and radiation protection

Ethics in diagnostic imaging: Over imaging and over diagnosis

Ethics and interventional radiology

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Medical ethics: Principles and application in radiology