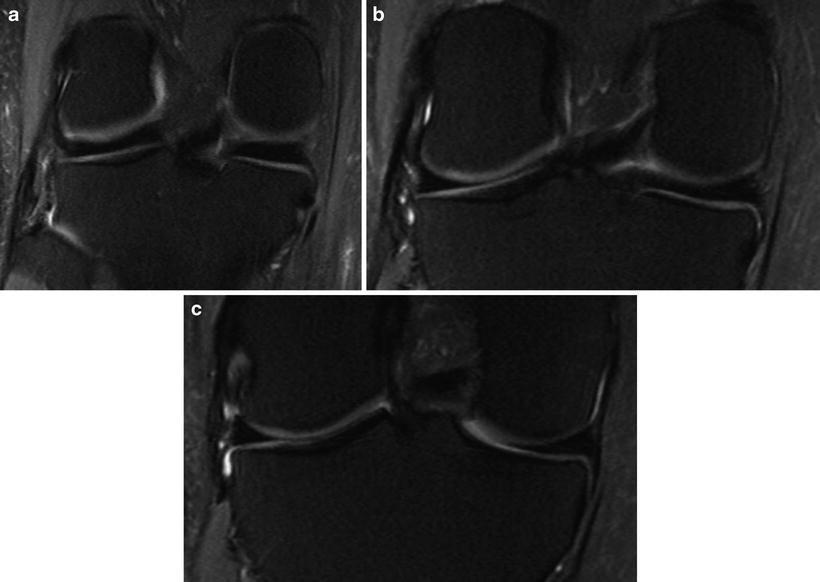

Fig. 3.1

Normal menisci. Sagittal proton density (PD) images through normal medial (a) and lateral (b) menisci in cross section demonstrate the normal appearance of the anterior and posterior horns as black triangles. (c) Mid-coronal fat-suppressed T2 image demonstrates the normal triangular appearance of the bodies of both menisci. (d) Far sagittal image of the lateral meniscus cuts through the edge shows the bow tie appearance. Arthroscopic images of the normal medial (e) and lateral (f) menisci demonstrate the smooth surfaces and edges

The medial meniscus is larger, more oblong, and normally has a larger posterior horn than anterior horn in cross section. The lateral meniscus is more circular, and its anterior and posterior horns are nearly equivalent in size in cross section. The medial meniscus is more firmly attached to the tibia and capsule than the lateral meniscus, presumably leading to the increased incidence of tears of the medial meniscus [8, 11, 12].

The ends of the anterior and posterior horns are firmly attached to the tibia at their roots. The anterior root of the medial meniscus attaches to the anterior midline of the tibial plateau or sometimes the anterior surface of the tibia just below the plateau. The posterior root of the medial meniscus attaches to the tibia, just anterior and medial to the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). The anterior root of the lateral meniscus attaches to the tibia, just lateral to the midline and posterior to fibers of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). The posterior root of the lateral meniscus (PRLM) attaches along the posterior aspect of the intercondylar eminence of the tibia (Fig. 3.2a–c) [8, 12–14].

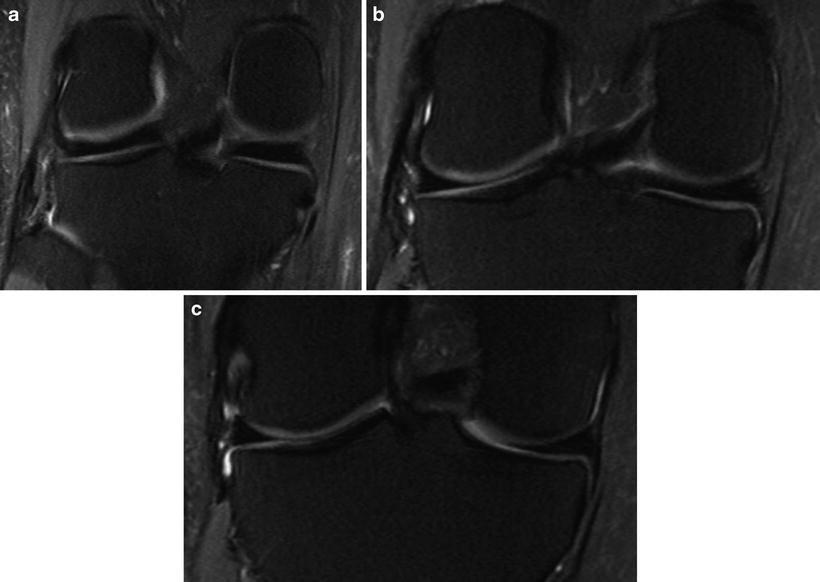

Fig. 3.2

(a)–(c) Normal posterior meniscal roots. Fat-suppressed T2 coronal images from posterior (a) to anterior (c) show the posterior horns of the menisci inserting into the tibia at the root ligament attachments alongside the posterior cruciate ligament

MRI of Meniscal Tears: Criteria and Accuracy

Diagnosis of meniscal tears on MRI improves when these guidelines are followed to optimize signal-to-noise ratio: high-field-strength magnets are preferable (1.5 T and stronger); a high-resolution surface coil should be used; the field of view should only encompass the necessary structures and routinely be 16 cm or less; image slices should not be too thick (3–4 mm); and the matrix size should be at least 256 × 192 or higher [15]. Some authors have suggested that many tears are best seen on sequences with a low echo time, namely, T1-weighted and proton density sequences [15]. However, it is the authors’ experience that tears are often better seen on the T2 images. This is probably related to fluid being more pronounced on the T2 sequences and subsequently accentuates fluid-filled defects in the meniscal tear.

A normal meniscus is low signal on all sequences. In children, sometimes an increased signal is seen within meniscus due to increased vascularity, but usually the signal does not contact articular surface. It is important to know the age of the patient when interpreting the MRI. Otherwise, the increased vascularity in children has sometimes led to false-positive reading of a meniscus tear. Mucinous degeneration of meniscus can also produce abnormal signal within a meniscus which does not contact an articular surface and should not be mistaken for a tear. This has also been described as grade 2 signal [12, 16, 17] (Fig. 3.3).

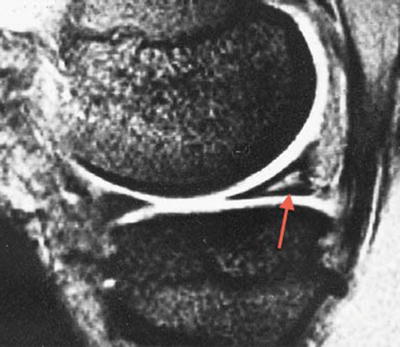

Fig. 3.3

Sagittal fat-suppressed T2 image of a 14-year-old patient showing a grade 2 signal in the posterior horn of the medial meniscus (PHMM). Note that signal does not contact articular surface

The most common criterion for diagnosing meniscus tear on MRI is an increased signal extending in a line or band to the articular surface. Another finding is the abnormal size or shape of the meniscus, which would indicate damaged surfaces [12, 16, 17]. Studies by Kaplan and colleagues [18] and De Smet and coworkers [19] showed that the abnormal signal must unequivocally contact the surface of the meniscus. Although it may seem easy to read a meniscus as torn from an MRI, it is actually sometimes difficult to interpret whether the abnormal signal comes close to or actually touches the surface.

To provide a greater degree of accuracy, De Smet advocated the “two-slice-touch rule.” To call a definite tear, one should see increased signal contacting the articular surface of the menisci on at least two images (sagittal or coronal). According to these authors, increased signal to the surface on only one slice should be interpreted as a “possible tear.” Cases of only one abnormal slice correlated to tears at arthroscopy 55 % of the time for the medial meniscus and 30 % for the lateral [19] and only 43 and 18 % in a follow-up study 13 years later [20].

Accuracy of diagnosing meniscus tear with these criteria has been good. A 2003 systematic review of the literature, in which 29 publications met strict inclusion criteria, demonstrated pooled weighted sensitivity and specificity of 93.3 % and 88.4 % for the medial meniscus and 79.3 % and 95.7 % for the lateral meniscus, respectively [21]. Subsequent studies show improvement in these numbers [20, 22].

Most meniscal tears are visible and best seen on sagittal images. This is because most tears occur in the posterior horns [12]. However, one study showed that some tears are better seen or only seen on coronal images [23]. More recently, few reports suggest very thin axial images through the menisci to improve accuracy and tear description [24]. Fortunately, the MRI scan includes images in all three planes, and all three should be looked at carefully. Specific tear orientations vary and may only be clear in one of the three planes.

Patterns of Meniscal Tears

Whether a torn meniscus is reparable depends on the type or pattern of tear, its location, and the quality of the meniscal tissue. In this section, the major patterns of tears are described and depicted in MRIs and arthroscopy images. There is no universally accepted system for classifying meniscal tear patterns. A classification system developed by the International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery, and Orthopedic Sports Medicine [25, 26] is used here, and associated names when they are in common use are provided. These patterns include longitudinal-vertical, bucket handle, horizontal, radial, vertical flap, horizontal flap, and complex [25, 26].

Longitudinal Tears: Case 1 (Fig. 3.4a–d)

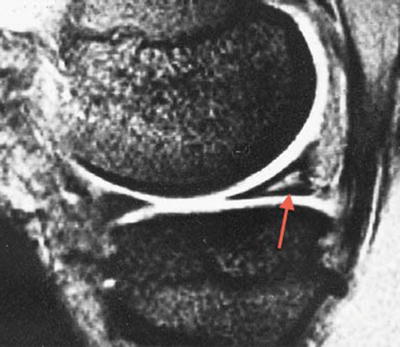

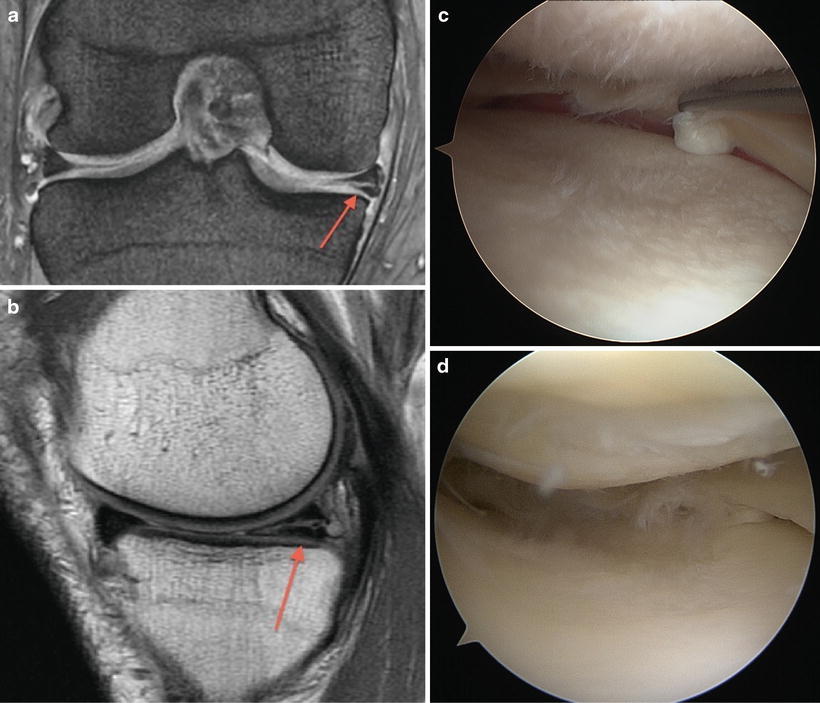

Fig. 3.4

Longitudinal-vertical tear. Sagittal PD (a) and fat-suppressed T2 (b) images show a longitudinal tear (arrow) in the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus (PHLM). (c) Coronal fat-suppressed T2 image showing the longitudinal tear. (d) Arthroscopic image of the same patient shows a probe in the longitudinal PHLM tear

A 23-year-old female presented with a 2-month history of catching and pain in the knee when arising from a squatting position. Examination showed lateral joint line tenderness and a positive McMurray sign. The MRI revealed a longitudinal tear in the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus. Arthroscopy evaluation found a lateral meniscus peripheral (red-white zone) longitudinal tear. The patient underwent an all-inside lateral meniscus repair.

Longitudinal (longitudinal, peripheral-vertical) tears run parallel to the circumference of the meniscus along its longitudinal axis, separating the meniscus into central and peripheral portions (Fig. 3.4a–d). They may contact articular surfaces of the meniscus. Longitudinal tears usually are the result of a specific injury, typically accompanying ACL tears, and usually start in the posterior horn [11, 12]. These lesions frequently occur in the periphery of the meniscus and are often amenable to repair.

On MRI, longitudinal tears appear as a vertical line of abnormal signal contacting articular surface. They maintain a relatively constant distance from the periphery of the meniscus [17].

Bucket-Handle Tears: Case 2 (Fig. 3.5a–d)

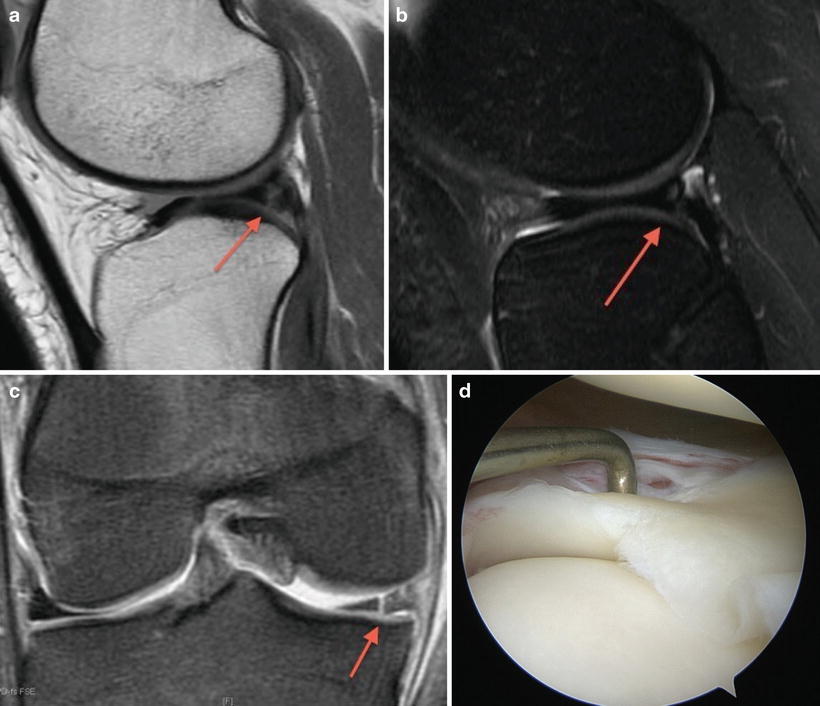

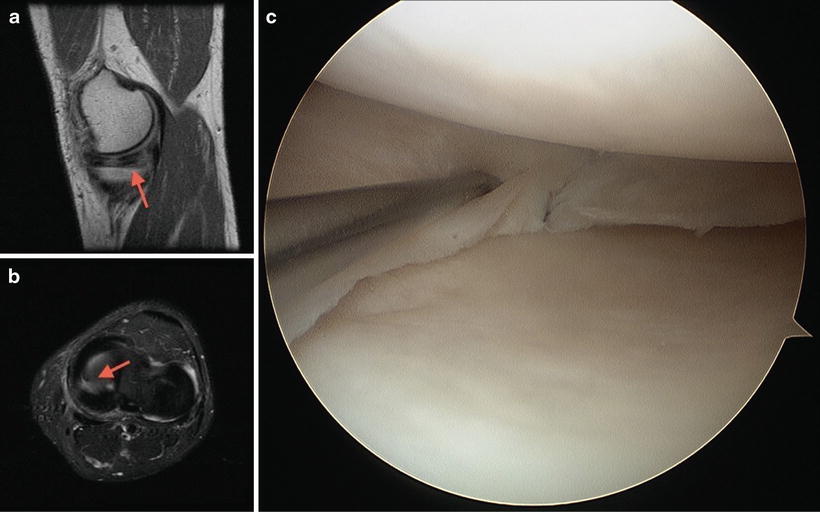

Fig. 3.5

Displaced bucket-handle tear. (a) Coronal fat-suppressed T2 image shows truncation of the body of the medial meniscus with fragment displaced into the notch. (b) Sagittal fat-suppressed T2 image shows the double PCL sign, representing the displaced meniscal fragment lying below the PCL. (c, d) Arthroscopic image demonstrates meniscal fragment displaced into the notch

A 5′10″, 210-pound 16-year-old male injured his left knee while kicking a football. He presented after a few months with symptoms of instability. Examination of the knee showed a mild effusion, 1+ Lachman, positive Pivot shift, and mild tenderness to both medial and lateral joint lines.

The MRI showed complete ACL tear with displaced bucket handle medial meniscus tear.

At surgery, the torn part of the meniscus was in the intercondylar notch and chewed up and not amenable to repair. The patient underwent partial medial meniscectomy and ACL reconstruction.

If a horizontal tear involves a long segment of the meniscus, the central fragment may displace centrally from the peripheral portion of the meniscus [17, 27]. Viewed from above, it resembles the handle on a bucket. The fragment commonly displaces into the intercondylar notch, although it may predominantly displace anteriorly [16]. If it displaces anteriorly, a portion of the displaced fragment may be visible in the intercondylar notch.

Bucket handle tears (BHT) often cause pain and mechanical symptoms, such as locking, catching, and giving way [16]. They are more frequent in the medial meniscus than the lateral and often occur in conjunction with ACL tears [27–29].

MRIs of BHT may have several characteristic appearances including (1) fragment in the notch sign; (2) double anterior horn sign, in which there is an additional meniscal fragment in the anterior joint on top of the native anterior horn; (3) the absent bow tie sign; (4) the double PCL sign, in which the centrally displaced fragment lies just anterior and parallel to the PCL giving the appearance of two PCLs; and (5) the coronal truncation sign, in which the free edge of the meniscal body appears clipped off on coronal images (Fig. 3.5a–d) [30–32].

Horizontal Tears: Case 3 (Fig. 3.6a–d)

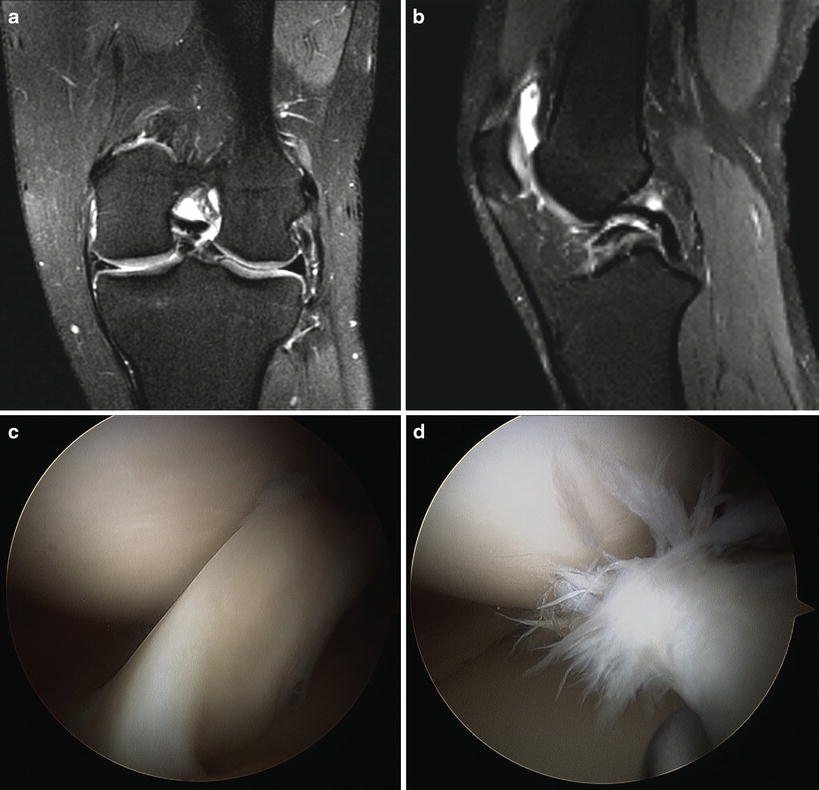

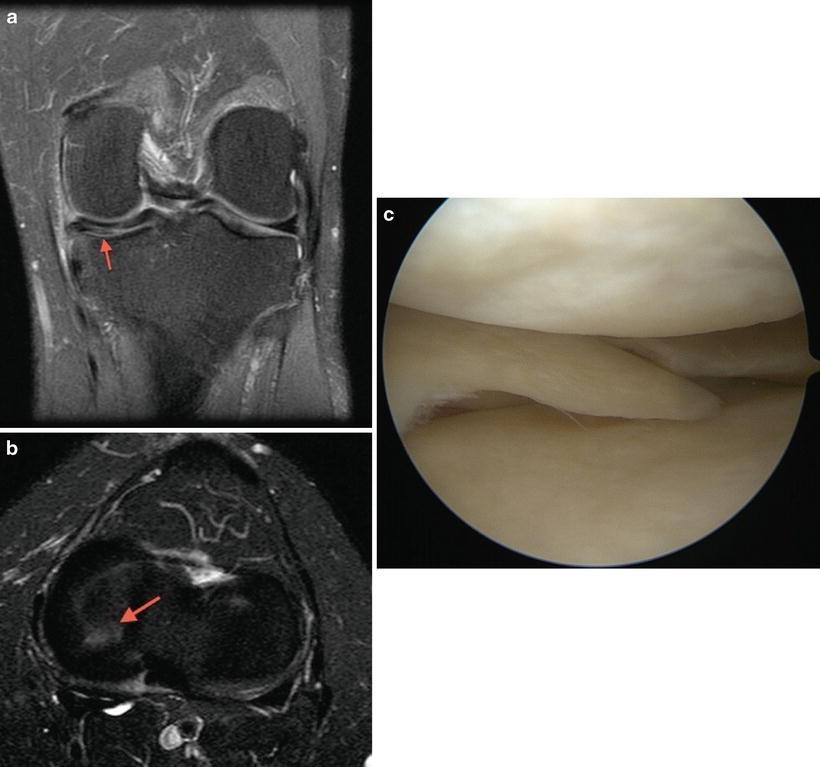

Fig. 3.6

Horizontal tear. Sagittal (a) and coronal (b) PD images show a horizontal tear (arrow). (c) Arthroscopic image in the same patient showing the horizontal PHMM tear. (d) Arthroscopic image of another patient showing horizontal PHMM tear

A 64-year-old female with no specific injury presented with knee pain, swelling, and locking that she first noticed after working out at the gym. Exam showed a mild effusion and medial joint line tenderness.

Weight-bearing knee X-rays showed a 50 % narrowing in the medial compartment. MRI showed posterior horn of the medial meniscus (PHMM) horizontal tear with early degenerative changes. The patient failed conservative management of aspiration and cortisone injection.

Arthroscopy revealed a horizontal tear of PHMM, and a partial medial meniscectomy was performed.

Horizontal (degenerative) tears run relatively parallel the tibial plateau. Most horizontal tears extend to the inferior articular surface. These tears are usually degenerative in nature and usually not associated with a discrete injury [12, 16]. These tears may occur in the posterior horn, body, or anterior horn.

Radial Tears: Case 4 (Fig. 3.7a–c)

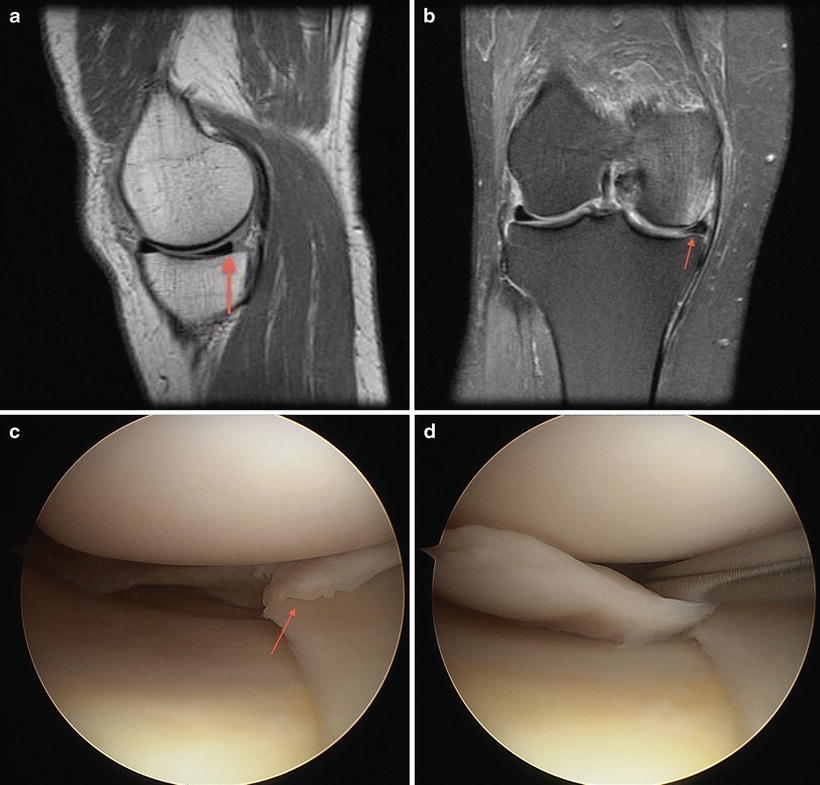

Fig. 3.7

Radial tear. Sagittal PD (a) and fat-suppressed axial T2 (b) images show a radial tear (arrows). (c) Arthroscopic image in the same patient demonstrates this radial tear

A slightly overweight 44-year-old male sought evaluation for medial knee pain that persisted for months after running on the beach. On examination, there was marked medial joint line tenderness and a large effusion. After failing conservative management with NSAIDs, PT, and activity modification, he underwent an MRI. This scan showed a radial MMT. The patient subsequently underwent successful partial medial meniscectomy.

Radial tears comprise approximately 15 % of tears in some surgical series [33, 34]. They are vertically oriented but extend perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the meniscus. Radial tears start at the free edge of the meniscus and may extend through part of its circumference or all the way to the peripheral margin [17]. These tears commonly occur at the center of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus or at the junction of the anterior horn and body of the lateral meniscus [12].

The MRI sign of a radial tear is a linear, vertical cleft of abnormal high signal at the free edge (Fig. 3.7a–c). For radial tears that are oriented obliquely, one may observe the marching cleft sign, because the location of the vertical cleft of abnormal high signal shifts position from one image to the next [12, 33]. Radial tears are often filled with joint fluid and stand out more on fat-suppressed T2-weighted images [34]. Axial images can be especially helpful in identifying some radial tears and giving a realistic appreciation of their depth [12]. Radial tears are exceptions to the two-slice-touch rule since tear can lie between image slices in one plane.

Vertical Flap Tears: Case 5 (Fig. 3.8a–c)

Fig. 3.8

Vertical flap (oblique) tear. (a) Coronal fat-suppressed T2 image shows radial component of the tear. (b) Axial fat-suppressed T2 image shows in detail the shape of the tear (arrow). (c) Arthroscopic image of the same patient demonstrates this vertical flap tear

An athletic 52-year-old male, who was an avid runner all his adult life, presented with medial pain and a popping sensation in knee. There was no history of a specific knee injury. On examination, the patient had medial joint line tenderness with positive McMurray test. The MRI revealed a vertical flap (oblique) tear of the medial meniscus. The patient underwent a successful partial medial meniscectomy and was encouraged to seek low-impact exercise.

Vertical flap (oblique, flap, parrot’s beak) tears are unstable tears and occur in younger patients. They are usually due to an acute injury [16]. They resemble radial tears: they typically begin as a vertical tear at the free edge of the meniscus and extend radially; however, they change their radial orientation and turn to run parallel to the meniscus [16]. The unstable portion of meniscus separated by this tear resembles a parrot’s beak.

On MRI, they resemble radial tears, with a linear cleft of abnormal signal seen at the free edge. However, the tear changes plane of orientation over its course. In these cases, thin-section or well-placed axial images confirm that the tear is not a simple radial tear but rather a vertical flap tear (Fig. 3.8a–c).

Horizontal Flap Tears: Case 6 (Fig. 3.9a–d)

Fig. 3.9

Horizontal flap tear. (a) Sagittal PD image demonstrates a truncated, irregular appearance to the PHMM (arrow). (b) Coronal fat-suppressed T2 image shows truncated and abnormal medial meniscus (arrow). (c, d) Arthroscopic images demonstrate the displaced flap extending peripherally (arrow, c) followed by probing of the flap (d)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree