(1)

Department of Pediatric Radiology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX, USA

Abstract

In this chapter miscellaneous inflammatory, tumoral, and other non-trauma entities are considered, such as atlanto-occipital instability, histiocytosis X, and spinal stenosis.

Inflammation–Infection

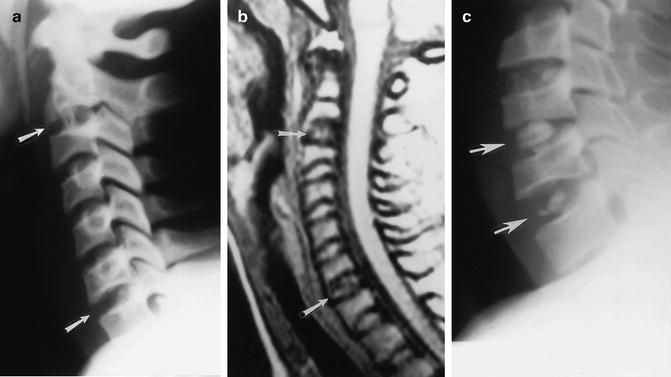

The most common inflammatory processes leading to cervical spine instability are the collagen vascular diseases [1, 2], primarily rheumatoid arthritis. These conditions lead to ligament instability, which most often, as far as the cervical spine is concerned, involves the upper and lower portions of the spine. Initially, the apophyseal joints are involved, with the joint space first becoming indistinct and then obliterated (Fig. 6.1a). Later, as the disease process progresses, fusion of the apophyseal joints and indeed, the posterior elements of the cervical vertebra, can occur (Fig. 6.1b). This is most likely to occur with Still’s disease, the most aggressive form of rheumatoid arthritis. In the upper cervical spine, atlantoaxial instability also can be seen, and it results in marked displacement of C1 on C2 (Fig. 6.1c).

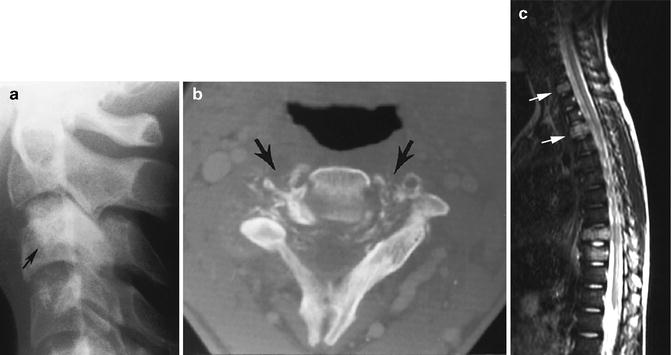

Fig. 6.1

Rheumatoid arthritis. (a) Note obliteration of the apophyseal joint (arrow) in the lower cervical spine. (b) In this patient with Still’s disease there is complete fusion of the posterior elements of the cervical spine (arrows). The apophyseal joints are completely obliterated. (c) C1–C2 dislocation with marked increase in the predental distance (arrow)

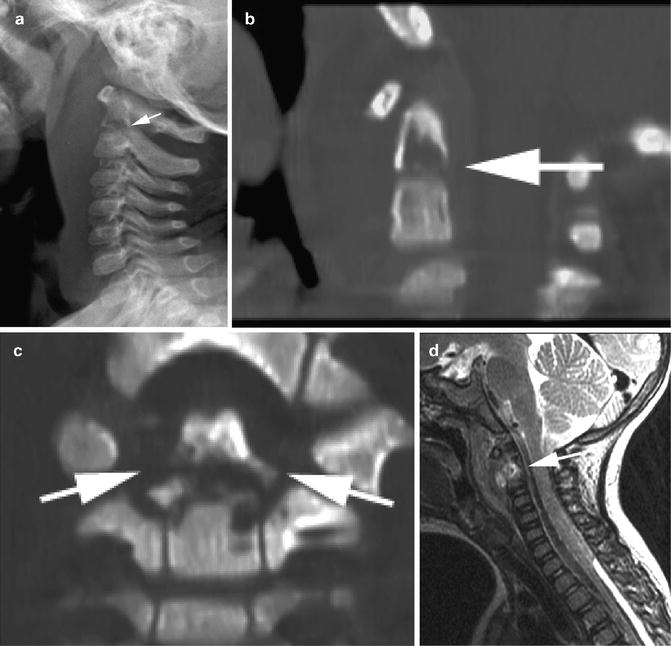

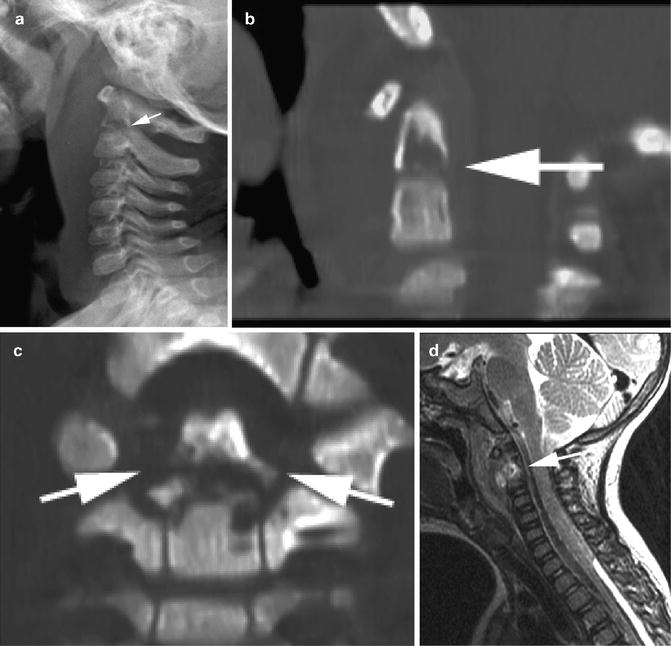

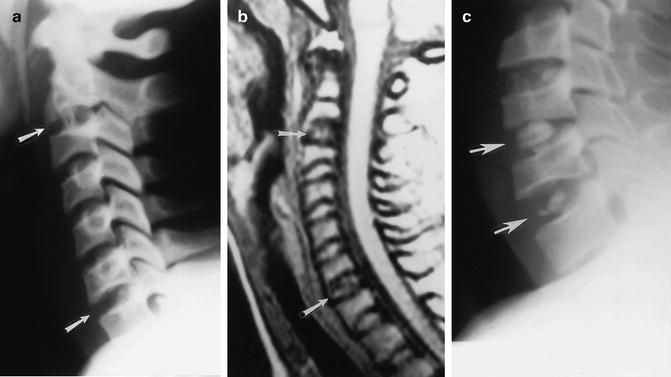

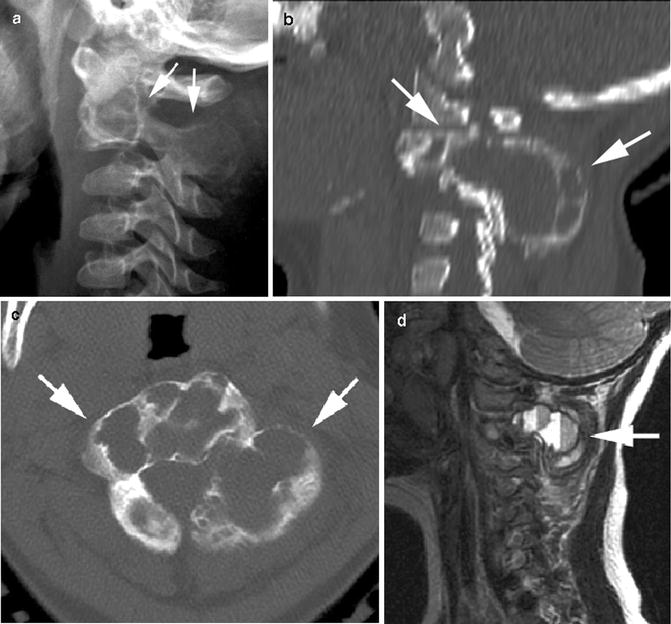

Osteomyelitis–diskitis of the cervical spine is not as common as it is in the thoracic and lumbar portions of the spine in children. In the lumbar spine, the infection usually is secondary to Staphylococcus aureus infection. This problem, however, basically does not occur in the cervical spine. In the thoracic spine, tuberculous infections are more common; but once again, the problem is uncommon in children. Nonetheless, when these infections occur there is destruction of the involved intervertebral disk space, along with bony resorption and destruction of the adjacent vertebral end plates. As a result, the disk space narrows, the end plates become indistinct, and loss of bony substance occurs. In other more common cases there is extensive destruction of the vertebra and in some cases associated destruction of the apophyseal joints (Fig. 6.2). With bacterial and tuberculous infections, disk space narrowing secondary to disk and bony destruction is common, but with fungal disease the disk often is preserved. Osteomylitis can involve the vertebral body, the dens [3], or the neural arch [4].

Fig. 6.2

Infection; osteomyelitis. (a) Osteomyelitis of C2. Note destruction of the body and dens of C2 (arrow). There is pronounced prevertebral soft tissue swelling. (b) Sagittal reconstructed CT demonstrates the destruction (arrow). (c) Coronal reconstructed CT demonstrates destruction of the dens and the body of C2 (arrows). (d) Sagittal MR, T2-weighted study demonstrates increased signal in the area of osteomyelitis (arrow)

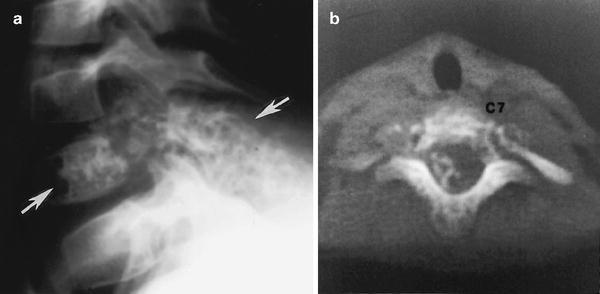

Another inflammatory condition of the cervical spine is the so-called “calcific diskitis of childhood” [3, 5–7]. This condition, of unknown etiology, but perhaps of viral origin [8], results in inflammation of the intervertebral disks and subsequent calcification. It is attended with pain but is self-limiting. In the early stages the disk spaces are enlarged and bulged [9]. This is best demonstrated with magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 6.3a, b), but eventually these disks undergo degeneration and calcification. Such calcification, of course, is readily visible on plain films (Fig. 6.3c). It can occur at multiple levels, and also can be seen in the thoracic spine. These disks also can herniate both anteriorly and posteriorly [10], but seldom is neurologic deficit attendant. Because the condition is self-limiting, it requires only supportive, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic therapy.

Fig. 6.3

Calcific diskitis. (a) Note a slight bulging configuration of two intervertebral disks (arrows). (b) Loss of signal in the two involved disks (arrows) is demonstrated by MRI. This patient also had calcification of an upper thoracic disk. (c) Typical calcified disks (arrows). Note the biconcave bulging configuration of the disk spaces ((a, b) Reproduced with permission from Swischuk LE, Stansberry SD. Calcific discitis: MRI changes in disks without visible calcification. Pediatric Radiology. 1991;21:365–6)

Neoplastic Diseases; Malignant and Benign

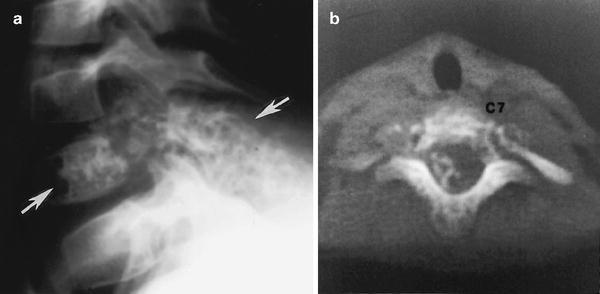

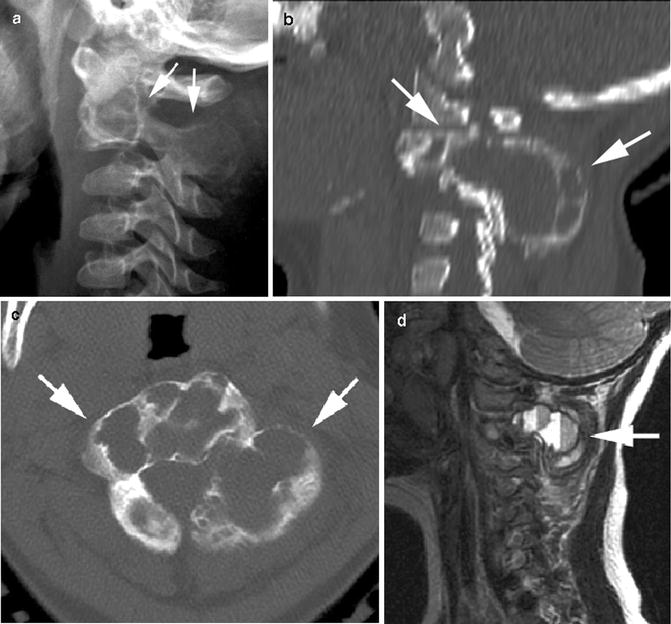

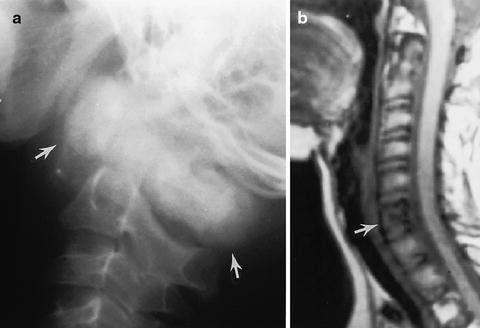

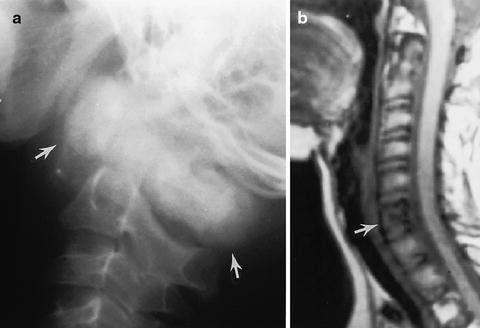

For the most part, benign tumors or tumorlike lesions consist of hemangiomas, aneurysmal bone cysts, and the occasional osteoid osteoma [11–14]. Hemangiomas characteristically produce a multiloculated expansile lesion, more often involving the posterior elements. However, vertebral body involvement also can occur (Fig. 6.4). Aneurysmal bone cysts appear much as they do in other portions of the skeleton and spine, producing lytic, slightly expansile, unless compression fractures supervene, lesions of the vertebral body (Fig. 6.5).

Fig. 6.4

Hemangioma. (a) Note the multiloculated, expansile, mixed lytic, and blastic appearance of this hemangioma, which extends from the vertebral body into the neural arch (arrows). (b) Axial CT study demonstrates the same findings

Fig. 6.5

Aneurysmal bone cyst. (a) Note the expansile lytic lesion involving the body and neural arch of C2 (arrows). (b) Sagittal reconstructed CT study demonstrates the same findings (arrows). (c) Axial CT demonstrates the expanding multiloculated nature of the lesion (arrows). (d) MR sagittal T2-weighted image demonstrates classic blood–fluid levels within the lesion (arrow)

Hemangiomas can be differentiated from aneurysmal bone cysts more clearly with MR than with CT imaging. With tomography the multiloculated nature and the primary location of the lesion, of course, are readily demonstrable, but it is with magnetic resonance imaging that differentiation between the two is more definitive. The reason for this is that hemangiomas retain high signal on T2-weighted sequences, while aneurysmal bone cysts produce heterogeneous signal. More importantly, however, aneurysmal bone cysts demonstrate pathognomonic blood–fluid levels (Fig. 6.5d). This generally is not seen with any other tumor or cystic bone disease.

Osteoid osteomas, of course, appear as they do at other sites in the spine. They produce sclerosis of the body or pedicle. Rarely, giant osteoid osteomas can be encountered (osteoblastomas). Similarly, one can occasionally encounter other benign tumors, such as chondromas, various fibrous tumors, and fibrous dysplasia.

Primary malignant tumors of the cervical spine also are very rare, except perhaps for Ewing’s sarcoma. The findings of these tumors are similar to those seen elsewhere in the skeleton and the vertebral column. Basically, in the spine they consist of the presence of a destructive lesion in the vertebral body with preservation of the adjacent intervertebral disk space. Most often, Ewing’s sarcoma involves the body of the vertebra, but the posterior elements of the vertebra also can be involved. Ewing’s sarcoma can also be multicentric, and in these cases it is difficult to determine whether the lesion truly is multicentric or is metastatic. In either case, however, one can encounter lytic or sclerotic lesions (Fig. 6.6).

Fig. 6.6

Ewing’s sarcoma. (a) C1 is markedly expanded and sclerotic (arrows) in this patient with metastatic or multicentric Ewing’s sarcoma. (b) Another patient. Magnetic resonance T1-weighted image demonstrates loss of signal in a vertebral body (arrow) involved with metastatic Ewing’s tumor

Bony involvement of the cervical spine with lymphoma and leukemia is rather uncommon. Metastatic disease, however, is more common and most often is due to metastatic neuroblastoma. In such cases there is destruction of the vertebral body with loss of vertebral height. The neural arches also can be involved, and pathologic fractures are common. Of course, the findings are not specific for neuroblastoma, for they can be seen with any number of malignant tumors (Fig. 6.7).

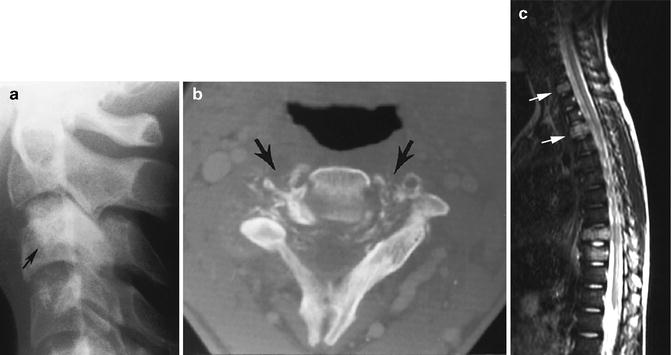

Fig. 6.7

Metastatic disease. (a) Note vague sclerosis of the body of C3 (arrow) in this patient with metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. (b) CT demonstrates the destructive nature of the metastatic lesion (arrows). (c) Another patient with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma. On this sagittal T2-weighted MR image note increased signal in a cervical vertebral body (upper arrow) and an upper thoracic vertebral body (lower arrow). Two other vertebra are involved in the lower thoracic spine with associated pathologic compression

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree