Miscellaneous Conditions

Lee F. Rogers

L. F. Rogers: Department of Radiology, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27157.

PAGET’S DISEASE (OSTEITIS DEFORMANS)

Paget’ disease is predominantly a disease of Caucasians. It commonly occurs in England, Australia, New Zealand, Scandinavia, Canada, and the northern United States but is relatively infrequent in the southern United States and is rarely encountered in Asia.21 The average age of onset is between 50 and 55 years and rarely before the age of 40. It is twice as common in men as in women. The cause is unknown.22

Paget’ disease may involve any bone in the body. It may affect a single bone and never extend to others; it may begin in one bone, with others becoming involved at a later date; and at times, it is widely distributed throughout the skeleton when first discovered.22 In order of frequency, the following bones are affected: pelvis, vertebrae, femur, skull, tibia, clavicle, humerus, ribs, and, rarely, the sternum, calcaneus, talus, phalanges, metatarsals, mandible, patella, and other sesamoid bones.22

Only 20% of patients are symptomatic, usually complaining of ill-defined pain at the site of involvement. Most cases are discovered incidentally at the time of a radiographic examination of the abdomen or a bone scan obtained to evaluate the possibility of metastatic disease. Characteristically there is elevation of the serum alkaline phosphatase, as much as 15 to 20 times normal. The serum calcium and phosphorus are usually normal; however, calcium may be markedly elevated in patients with Paget’ disease who are immobilized. Renal calculi or nephrocalcinosis may develop from hypercalciuria under these conditions.

Pathologically, Paget’ disease is characterized by destruction of bone (lysis) followed by attempts at repair. There is usually a combination of destruction and repair, but the destructive phase may predominate at some sites.

Roentgenographic Features

The radiographic appearance depends on the phase of the disease: lytic, reparative, or mixed. The principal radiographic findings are thickening of the cortex, coarsening of trabeculae, enlargement of bone, areas of lucency, patches of dense bone described as “cotton wool” or “cotton ball,” and evidence of bone softening.16,17 In the long bone, the process almost always involves the end of the bone extending into the diaphysis. In the pelvis, it usually involves some portion of the acetabulum. Healing of the lytic phase has been described as a result of treatment with diphosphonates and calcitonin.7,8

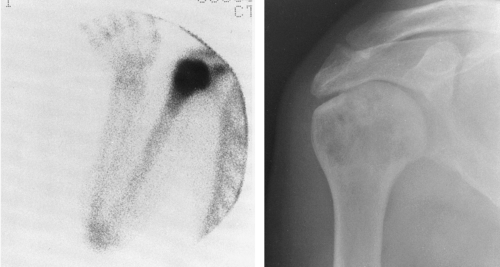

Pagetic bone takes up all radionuclide bone scanning agents avidly—in fact, more intensely than any other process. The diagnosis of Paget’ disease can be made on the basis of a bone scan because of this intense activity and the pattern of bone involvement—involvement of the end of the bone with variable extension into the shaft and often evidence of softening manifested by bowing of long bones and flattening of vertebrae (Fig. 7-1).

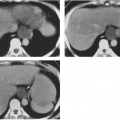

Computed tomography (CT) (see Figs. 7-3, 7-7B), mirrors the findings on plain film radiography in Paget’ disease; expansion, with cortical thickening, coarsening of the trabeculae, and focal sclerotic densities in intramedullary bone, the equivalent of “cotton balls.” The osteolytic phase demonstrates considerable thinning of the cortex of long bones and tables of the skull.12

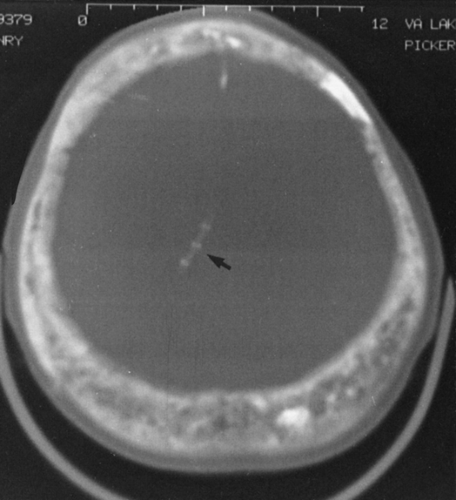

FIG. 7-3. Computed tomographic examination of Paget’s disease of the skull in a case with plain films similar to those in Fig. 7-2B. The skull is markedly increased in thickness, with a coarsened and thickened inner and outer table and a widened diploic space. A coarsened trabecular pattern in the diploic space and small foci of increased density give rise to the “cotton wool” appearance of the skull. The foci of sclerosis alternate with foci of lucency within the diploic space. A ventriculoperitoneal shunt (arrow) was necessitated by platybasia leading to hydrocephalus. |

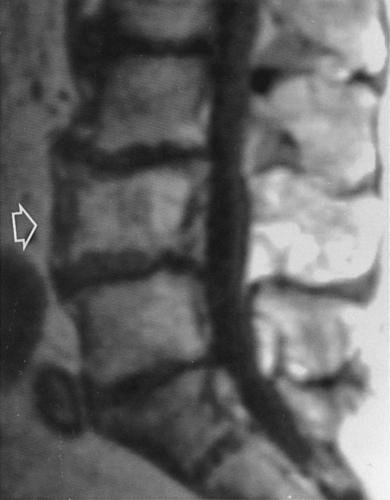

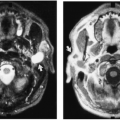

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) displays similar osseous changes as low signals on both T1- and T2-weighted images.23 The marrow signal in the intramedullary and diploic spaces is variable, with high-signal foci of fat seen on T1 (see Fig. 7-9) and high-signal foci of fibrovascular marrow on T2-weighted images.

Both CT and MRI are useful in the analysis of the complications of Paget’ disease (i.e., spinal cord or neural compression, basilar invagination, and sarcomatous degeneration). However, it is more likely that Paget’ disease will be encountered unexpectedly as an incidental finding when these techniques are used to evaluate for other diseases. Plain film correlation is advisable to avoid confusion.

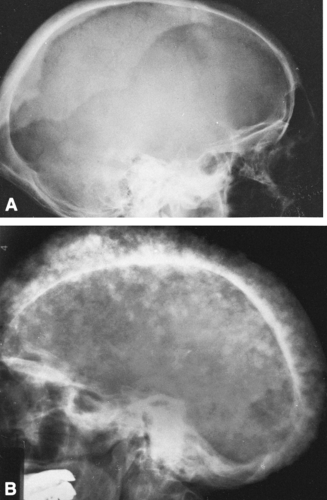

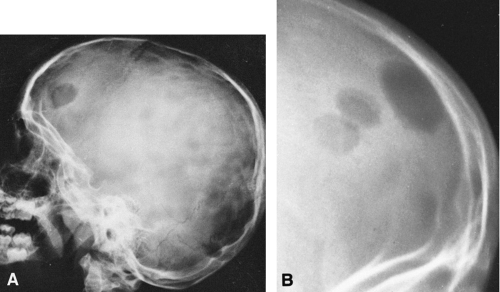

Skull

The classic expression of the lytic phase of Paget’ disease in the skull is known as osteoporosis circumscripta (Fig. 7-2A). This is a sharply demarcated area of radiolucency within which the architecture of the bone is poorly defined. The lesion usually involves the frontal or parietal bones and may enlarge slowly. Characteristically, the junction between the lucent and normal bone is very sharp. When repair begins, islands or patches of sclerosis appear, resembling cotton wool or cotton balls. The bones of the vault become thickened, usually only outward, and may measure 3 cm or more in thickness (Figs. 7-2B and 7-3). The outer edge of the lesion is better seen with a bright light. The base of the skull may be involved, and there may be basilar invagination (Fig. 7-2B) in which the cranium settles over the cervical spine and the craniovertebral junction protrudes into the base of the skull as a result of bone softening.

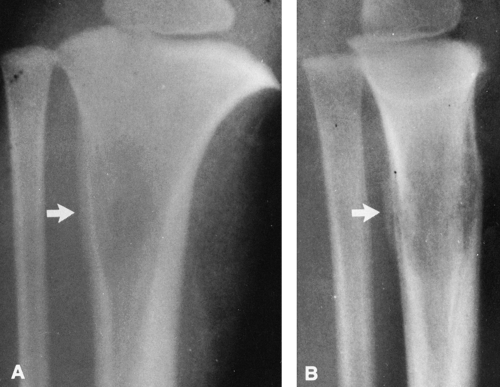

Long Bones

In long bones, Paget’ disease almost invariably extends to and involves the subarticular bone immediately adjacent to the joint (Figs. 7-4 and 7-5). The length of involvement is variable, but in some cases the entire bone is involved. The cortex is thickened, and the overall diameter of the bone is increased. The intramedullary cavity is maintained. The trabeculae are coarse and thickened and therefore radiographically prominent but remain in the same direction and relative position as they would in normal bone. Between the coarsened trabeculae, cyst-like radiolucencies are often identified. The thickened cortex suggests increased strength, but actually the bone is weakened, as manifested by bowing of long bones, which is more pronounced in the lower than the upper extremities. Characteristically, the femur bows outward and the tibia anteriorly.

The osteolytic phase is less commonly encountered in long bones than is the mixed form just described. Inactivity

(e.g., bed rest, immobilization) tends to accentuate bone destruction. The osteolytic phase is characterized by a clearly demarcated zone of radiolucency extending a variable distance into the diaphysis from the end of the bone. The process is often referred to as a “blade of grass” (Fig. 7-6), because the lucency is elongated and involves only a segment of the cortex, the periphery of the lesion is clearly demarcated, and its distal margin is flame shaped or V-shaped and thus resembles a blade of grass.

(e.g., bed rest, immobilization) tends to accentuate bone destruction. The osteolytic phase is characterized by a clearly demarcated zone of radiolucency extending a variable distance into the diaphysis from the end of the bone. The process is often referred to as a “blade of grass” (Fig. 7-6), because the lucency is elongated and involves only a segment of the cortex, the periphery of the lesion is clearly demarcated, and its distal margin is flame shaped or V-shaped and thus resembles a blade of grass.

Pathologic fractures are common and are characteristically transverse rather than oblique or spiral as in normal bone. These have been referred to as “banana fractures.” Incomplete, transverse radiolucent fissures called pseudofractures are common in the cortex along the convex side of severely involved bowed bones (see Fig. 7-4). They are often multiple. Pathologic fractures may be initiated at the site of a pseudofracture.

Pelvis

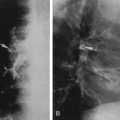

The most common expressions of Paget’ disease in the pelvis are thickening of the cortex, which is best appreciated in the pubic bones, and coarsening of the trabecular pattern, which is most easily recognized around the acetabulum and the margins of the sacroiliac joint (Fig. 7-7). Cyst-like radiolucent spaces may be encountered. Larger areas of radiolucency are common in the central portion of the iliac bones. The sacrum may be the first or the only bone involved, manifested by a thickening of the cortex that is best appreciated in the sacral foraminal lines. Coarse trabeculation causes a distinctive crosshatch pattern in the body of the sacrum. Less commonly, variable-sized patches of sclerosis may occur. These may resemble osteoblastic metastasis, but careful observation usually reveals that they are associated with typical coarse trabeculation and thickening of the cortex not encountered in metastasis (Fig. 7-7). Often this can be done simply by comparison with the opposite side, but when both sides are involved, this is a greater problem. Because of bone softening, there may be intrapelvic protrusion of the acetabulum, termed protrusio acetabuli.

Spine

The disease usually affects multiple vertebrae, occasionally is solitary, but rarely is universal. Involvement of the vertebral body is prominent, but closer examination usually discloses involvement of the posterior elements, the laminae, the pedicles, and the transverse and spinous processes. The principal pattern of involvement is thickening of the cortex, which gives a broadened and somewhat smudged appearance. On the lateral view, owing to the cortical thickening, the vertebral bodies appear to be framed, the so-called “picture frame” vertebrae (Figs. 7-8 and 7-9). Similar changes can be seen within the pedicles and spinous process and occasionally the transverse process on the frontal view. The trabeculae within the vertebral body are coarsened. Occasionally the vertebrae are diffusely dense, with coarse trabeculae in a pattern similar to that seen in small bones of the hands and feet. The overall size of the vertebrae is increased, and softening results in compression. The vertebral bodies then appear flattened and slightly expanded. Expansion of pagetic bone may compromise the spinal canal, leading to spinal cord compression and neurologic symptoms.

Flat Bones

In the ribs and clavicle, the bones are thickened and there is a general increase in density across their entire width. The trabecular pattern is typically coarsened. One or more ribs may be involved. The lesion always extends to one or the other end of the bone.

Small Bones

Involvement of the small bones of the hands and feet is uncommon and almost invariably involves the entire bone. There are two principal patterns. In the calcaneus, prominent thickened trabeculae and thickening of the cortex occur, whereas in the phalanges, metacarpals, and metatarsals, the entire bone is enlarged and diffusely increased in density, and the trabecular pattern coarsened.

Complications

The most common complication is a fracture that is characteristically transverse and often initiated at the site of a pseudofracture (see Fig. 7-4).

Spinal cord compression may occur from expansion of the vertebral bodies.1 Extramedullary hematopoiesis has been described, appearing as a mass adjacent to involved vertebral bodies and possibly leading to spinal cord compression.22

Spinal epidural hematoma has also been reported in association with Paget’ disease of the spine.13

Spinal epidural hematoma has also been reported in association with Paget’ disease of the spine.13

Expansion of bone at the base of the skull may reduce the size of the neural foramen and canals, leading to neurologic deficits such as deafness.

Heart failure is considered by many to be a complication and is thought to be caused by arteriovenous fistulae within the involved bone. However, it is argued that most patients are older and their congestive heart failure is primarily related to concomitant arteriosclerosis. Arteriovenous shunting in pagetic bone is rarely responsible for cardiac failure.

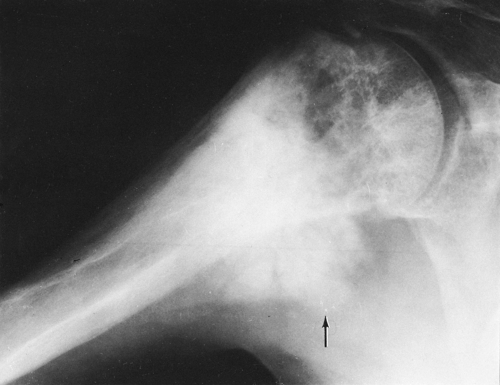

Primary malignant tumors may develop in areas of pagetic bone.18 Sarcomatous degeneration leads to osteogenic sarcoma in most cases (Fig. 7-10) and less commonly to fibrosarcoma. The incidence is approximately 1%. Nevertheless, Paget’ disease accounts for most primary osteogenic sarcomas after the age of 50. Giant cell tumors have also been reported. Tumors are more frequent in the pelvis and long bones and occur rarely in the vertebrae. The most common manifestation is an area of poorly defined destruction, with destruction of the overlying cortex and an associated soft-tissue mass. Periosteal reaction is infrequent. Fibrosarcomas are lytic, and osteosarcomas contain patches of sclerotic, blastic bone formation, particularly in the pelvis. Metastatic disease also occurs in the pagetic bone and cannot be differentiated from lytic primary tumors. Pathologic fractures are frequent complications of malignancy, and every pathologic fracture appearing in pagetic bone should be viewed suspiciously for evidence of an associated unsuspected malignancy.

HISTIOCYTOSIS X (RETICULOENDOTHELIOSIS)

The term histiocytosis X is the general designation for three conditions that range from the usually solitary, curable eosinophilic granuloma, through the disseminated process of Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, to the fulminating and rapidly fatal variety known as Letterer-Siwe disease. The clinical presentations of the three syndromes are distinctive, but they share common microscopic features that cannot be distinguished histologically by pathologists.

In Letterer-Siwe disease, lesions are widely disseminated throughout the body. It is a disease of infants and young children, who present with splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, generalized lymphadenopathy, a tendency to hemorrhage, and a secondary anemia. The course is rapid, and death occurs so early that radiographic changes often are not present, although the bone marrow may be extensively involved.

Hand-Schüller-Christian disease is a more benign process characterized by destructive lesions of the skull. It usually develops during childhood and at presentation the classic triad of diabetes insipidus, exophthalmos, and lesions of the skull may be seen. However, presentation with the classic triad occurs in a distinct minority of cases, usually before the age of 5 years. The clinical course may extend over a period of years. The flat bones (skull, pelvis, scapula, ribs, and mandible) are most frequently involved; less commonly, the long bones are affected.

Eosinophilic granuloma is the most benign of these conditions; it usually occurs as a solitary process in children or young adults. Lesions may respond well to curettage, steroid injection, or irradiation. Spontaneous regression may occur. It is widely distributed throughout the skeleton but is most often found in the skull, pelvis, femur, and ribs. Lesions are infrequent below the knee and elbow.

Roentgenographic Features

Letterer-Siwe disease, although disseminated, rarely produces radiographic findings. The radiographic findings in Hand-Schüller-Christian disease and eosinophilic granuloma are essentially the same and differ only in the number of lesions. Eosinophilic granuloma is more likely to be solitary and to occur in later childhood, adolescence, or early adult life. Hand-Schüller-Christian disease occurs during childhood, and multiple lesions are usually present.

In general, bone scanning is not as sensitive as radiography in the evaluation of the histiocytosis. Only 50% of the lesions or fewer may be disclosed by scintigraphy, and therefore radiographic skeletal surveys must be performed for the discovery of additional lesions.

Skull

There are solitary or multiple areas of bone destruction. The edges of the individual lesions are sharply defined, punched-out areas that are slightly scalloped or irregular but have no boundary zone of sclerosis. The lack of a sclerotic boundary is characteristic (Fig. 7-11). Typically, the lesion originates in the diplöe and involves one or both tables, causing a sharply outlined and slightly irregular translucent defect. The lesion has a beveled edge, caused by unequal destruction of the inner and outer tables. Rarely, a small fragment of bone remains within the radiolucency, resembling a sequestrum. In Hand-Schüller-Christian disease, the lesions may become very large and map-like (Fig. 7-11A). The lesions of eosinophilic granuloma tend to be smaller, on the order of 1 to 2 cm.

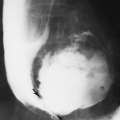

In the mandible, the lesions of histiocytosis cause destruction of bone without sclerotic reaction. The bone may completely

disappear around one or more of the teeth, causing them to appear as if they were floating (Fig. 7-12). This is characteristic of histiocytosis.

disappear around one or more of the teeth, causing them to appear as if they were floating (Fig. 7-12). This is characteristic of histiocytosis.

FIG. 7-12. Hand-Schüller-Christian disease. A lytic lesion in the left mandible surrounds a tooth, the so-called “floating” tooth. |

Patients may present with draining ears secondary to histiocytosis within the mastoids. Radiographic examination discloses a radiolucent focus of bone destruction within the temporal bone.

Flat Bones

In the pelvis and scapula, the lesions appear as radiolucent areas that may be bound by a rim of sclerosis. In the ribs, the lesions are often expansile and may have surrounding periosteal reaction.

Spine

Histiocytosis X causes extensive destruction of the vertebral body, leading to a uniform total collapse so that the body is thin and wafer-like, often referred to as vertebra plana (Fig. 7-13). Perivertebral soft-tissue masses may be identified in association with vertebral lesions. Vertebra plana in an adult should suggest the possibility of multiple myeloma, Gaucher’ disease, or Paget’ disease.

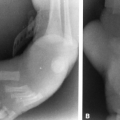

Long Bones

In the long tubular bones, the appearance of histiocytosis is somewhat different from that of the skull and is similar to that in flat bones. An area of bone destruction may be noted at any place along the length of the bone. It usually arises centrally but may be eccentric. The lesions may destroy or expand the cortex, and overlying periosteal new-bone formation is usually present (Fig. 7-14). The periosteal reaction is usually compact but may be laminated in younger children. At times, in young children, the lesion may have no visible outer or peripheral margin. Compact periosteal reaction is typical of histiocytosis X but is also noted in chronic infections. In younger children, the lesions may suggest Ewing’ tumor, but the geographic area of bone destruction and the compact nature of the periosteal reaction are more in keeping with histiocytosis.

GAUCHER’ DISEASE AND NIEMANN-PICK DISEASE

Gaucher’ disease is not a tumor but a metabolic disorder characterized by the abnormal deposition of cerebrosides in the reticuloendothelial cells of the spleen, liver, and bone marrow. These develop a characteristic histologic appearance and are known as Gaucher’ cells. A very large spleen and a moderately enlarged liver are clinical features of this disease, and roentgenographic evidence, particularly of the splenomegaly, is present.

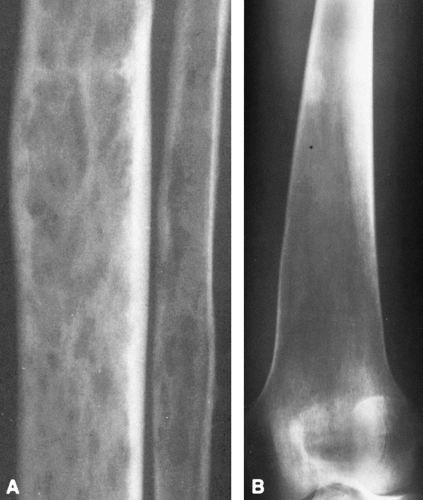

There is a wide spectrum of radiographic findings in Gaucher’ disease.19,25 Infiltration of the bone marrow by these cells may lead to patchy areas of cortical destruction similar to those seen in myeloma. In some cases, there is only a rather generalized demineralization (Fig. 7-15A). If the disease has existed for some time, expansion of the lower end of the femur may occur, resulting in the “Erlenmeyer flask” appearance (Fig. 7-15B). This is suggestive but not diagnostic of Gaucher’ disease.

Involvement of the vertebrae may lead to collapse of one or more vertebral bodies, which on occasion may be markedly compressed, thin, and wafer-like, as in vertebra plana. In the long bones, there may be numerous sharply circumscribed osteolytic defects resembling to some extent the lesions of metastatic carcinoma or multiple myeloma. The cortex is thinned and scalloped internally, and there may be periosteal new-bone formation over the involved area. Pathologic fractures of the femoral neck may occur (Fig. 7-16).

Occasionally, sclerotic areas are present. The skull and bones of the hands and feet are rarely affected.

Occasionally, sclerotic areas are present. The skull and bones of the hands and feet are rarely affected.

Infiltration of the bone marrow may compress and compromise the arterial supply to the end of a long bone, resulting in avascular necrosis. This is most commonly encountered in the head of the femur (see Fig. 7-16) and in the humerus. The radiographic features of avascular necrosis are described later. The extent of bone marrow involvement may be assessed by technetium-99m sulfur colloid (99mTc-SC) bone marrow scanning.13

Niemann-Pick disease is apparently a very rare variant of Gaucher’ disease occurring in families of whom about 50% are Jewish. It, too, is a form of lipid reticulosis, the lipid at fault being sphingomyelin. The effect on the bones is similar to that of Gaucher’ disease, but it occurs in infants (younger than 18 months of age) and is usually fatal within a year of onset.

HYPERLIPOPROTEINEMIAS

Primary familial hyperlipoproteinemias are a group of heritable diseases associated with an increase in plasma concentrations of cholesterol or triglycerides. They are subdivided into five major types, I through V, according to the plasma lipoprotein pattern.

Xanthomas may be apparent in all five types. Localized deposits occur in the tendons of the palm and dorsum of the hand, patellar tendon, Achilles tendon, plantar aponeurosis, and peroneal tendons; around the elbow; and in the fascia and periosteum overlying the lower tibia. Tendinous xanthomas produce nodular masses in tendons (Fig. 7-17) that are characteristic of this disorder. They rarely calcify. Subperiosteal xanthomas are associated with scalloping of the external cortical surface. Intramedullary lipid depositions are well defined, with sharp zones of transition between abnormal and normal bone. In the hands and feet, they may have a symmetrical distribution.