This article focuses on MR enterography in the evaluation of small bowel diseases, including the protocol, enteric contrast agents, imaging timing and sequence selection. It is becoming the first-line radiological investigation to evaluate the small bowel in patients diagnosed with Crohn disease, particularly in young adults, in whom ionizing radiation is a concern. A key question in the management of such patients is the assessment of disease activity. Knowledge of the location, severity, and presence of complications may assist in providing patients with appropriate treatment options. Other small bowel diseases beyond Crohn disease will also be discussed.

Key points

- •

MR enterography is rapidly becoming the first-line radiological modality to evaluate patients with Crohn disease in whom multiple serial examinations may be needed to assess progression of the disease, detect complications, and monitor response to therapy.

- •

MR enterography is a useful technique for the evaluation of intraluminal and extraluminal small bowel disease, particularly in adolescent and young adults with Crohn disease.

- •

The main advantages of MR enterography and MR enteroclysis are lack of ionizing radiation, the ability to provide dynamic information regarding bowel distention and motility, and the relatively safe intravenous contrast agent profile.

- •

Mural hyperenhancement is the most sensitive finding in patients diagnosed with Crohn disease presenting with active inflammation. This finding is significantly correlated to histology as well as to the clinical findings of active disease.

- •

One of the most important roles of MR enterography is to assess disease activity and differentiate fibrotic stenosis from active inflammation, which has a different treatment.

- •

Beyond Crohn disease, MR enterography can play a role in the evaluation of small bowel neoplasms and celiac disease.

Introduction

The small bowel has always been considered a structure of difficult propedeutic evaluation, mainly because of its length and position in the digestive tube between the stomach and the large bowel. Traditionally, the radiological evaluation of the small bowel disorders has always been performed by means of barium examinations, such as conventional enteroclysis and small bowel follow-through (SBFT) ( Fig. 1 ). The latter was, for many years, considered the standard imaging method.

However, cross-sectional techniques, especially CT scans and MR imaging, optimized for small bowel imaging are currently replacing these conventional techniques and playing an increasing role in the noninvasive evaluation of small bowel disorders. These methods have several advantages over traditional barium examinations because of improvements in spatial and temporal resolution combined with improved bowel distending agents ( Fig. 2 ). They allow the evaluation of the lumen and the mucosal surface and the intestinal wall, as well as identification of associated mesenteric and extra enteric findings. Furthermore, CT scans and MR imaging allow the visualization of the entire bowel without overlapping loops.

CT enterography is widely used in the evaluation of small bowel diseases. However, recently, the knowledge of the risks of ionizing radiation has been increasing and there has been an emphasis on reducing patient exposure by using alternative imaging tests, including ultrasound and MR imaging. The use of ionizing radiation has received growing attention mainly in the setting of small bowel inflammatory disorders when these chronic conditions manifest early in life. MR enterography is an alternative method, considering its lack of ionizing radiation. Both MR enterography and CT enterography, clearly demonstrate endoluminal, mural, and extramural enteric changes. In addition, they provide functional information on the peristalsis of the involved segment. The accuracy of the MR enterographic methods (MR enterography and MR enteroclysis) for the evaluation of Crohn disease is well described in the literature.

Introduction

The small bowel has always been considered a structure of difficult propedeutic evaluation, mainly because of its length and position in the digestive tube between the stomach and the large bowel. Traditionally, the radiological evaluation of the small bowel disorders has always been performed by means of barium examinations, such as conventional enteroclysis and small bowel follow-through (SBFT) ( Fig. 1 ). The latter was, for many years, considered the standard imaging method.

However, cross-sectional techniques, especially CT scans and MR imaging, optimized for small bowel imaging are currently replacing these conventional techniques and playing an increasing role in the noninvasive evaluation of small bowel disorders. These methods have several advantages over traditional barium examinations because of improvements in spatial and temporal resolution combined with improved bowel distending agents ( Fig. 2 ). They allow the evaluation of the lumen and the mucosal surface and the intestinal wall, as well as identification of associated mesenteric and extra enteric findings. Furthermore, CT scans and MR imaging allow the visualization of the entire bowel without overlapping loops.

CT enterography is widely used in the evaluation of small bowel diseases. However, recently, the knowledge of the risks of ionizing radiation has been increasing and there has been an emphasis on reducing patient exposure by using alternative imaging tests, including ultrasound and MR imaging. The use of ionizing radiation has received growing attention mainly in the setting of small bowel inflammatory disorders when these chronic conditions manifest early in life. MR enterography is an alternative method, considering its lack of ionizing radiation. Both MR enterography and CT enterography, clearly demonstrate endoluminal, mural, and extramural enteric changes. In addition, they provide functional information on the peristalsis of the involved segment. The accuracy of the MR enterographic methods (MR enterography and MR enteroclysis) for the evaluation of Crohn disease is well described in the literature.

Cross-sectional methods: enterography versus enteroclysis

The optimal distention of small bowel loops plays a pivotal role in the correct evaluation of small bowel diseases at cross-sectional imaging. Collapsed loops may result in an apparently thickened wall, which can hide lesions or mimic disease.

The main difference between MR enteroclysis and MR enterography is the use of nasoduodenal intubation under fluoroscopic guidance in enteroclysis for optimal distension of the small bowel, whereas with enterography the contrast agent is given orally. Both technics involve the administration of a large volume of fluid to produce small bowel filling and distension. Enteroclysis is considered a method that yields a better distention, mainly of the proximal jejunal loops, but it has the main disadvantage of placing the nasoenteric tube that may cause patient discomfort and may also be related to various logistical and technical difficulties ( Fig. 3 ). Moreover, this enterographic method uses ionizing radiation exposure (tube placement under fluoroscopic guidance) and is sometimes difficult to perform. There is a general preference among radiologists for performing MR enterography over MR enteroclysis because it is easier, less time consuming, and better tolerated by the patients.

The advantages and disadvantages of MR enterography, MR enteroclysis and CT enterography are summarized in Table 1 .

| MR Enterography | MR Enteroclysis | CT Enterography | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Availability | Less available | Less available | Widely available |

| Cost | Medium | Higher costs | Lower costs |

| Enteric contrast delivery | Oral administration | Administration through a nasoenteric tube | Oral administration |

| Length of examination | 30 min | 60 min, considering placement of nasoenteric tube | Fast examination time (scanning time <1 min) |

| Invasive nature | Noninvasive | Invasiveness related to the placement of a nasoenteric tube to administer the enteric contrast material | Noninvasive |

| Visualization of the small bowel wall | Displays the entire thickness of the bowel wall and perienteric tissues | Displays the entire thickness of the bowel wall and perienteric tissues | Displays the entire thickness of the bowel wall and perienteric tissues |

| Distention of the small bowel loops | Suboptimal distention and filling of the proximal small bowel (jejunal loops) | Yields the best distention, mainly of the jejunal loops | Suboptimal distention and filling of the proximal small bowel (jejunal loops) |

| Exposure to ionizing radiation | No | Needs of additional ionizing radiation exposure for duodenal intubation | Yes |

| Examination quality | Variable | Variable | Consistent |

| Multiplanar imaging capability | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Soft-tissue contrast resolution | Excellent | Excellent | Medium |

| Spatial resolution | Lower | Lower | Higher, with submillimeter near-isotropic voxel |

| Temporal resolution | Lower | Lower | Higher |

| Dynamic information regarding bowel distention and motility | Yes | Yes | No |

| Intravenous contrast agent | Use of a relatively safe intravenous contrast agent (gadolinium-based agents) | Use of a relatively safe intravenous contrast agent (gadolinium-based agents) | Iodinated contrast agent with the risk of serious allergic reaction and nephrotoxicity |

| Multiphase postcontrast dynamic imaging | Possibility to perform | Possibility to perform | Limited ability to perform multiphasic examination due to radiation exposure |

Technical considerations

Although there is no consensus regarding the ideal technique, there are some trends in performing MR enterography: the use of hyperosmolar oral contrast, prone-position, acquisition of the images mainly in the coronal plane using fast sequences, evaluation of the motility of the small bowel with the cine dynamic sequences, and dynamic evaluation of the intravenous contrast uptake. The prone position is preferred because there is a thinner volume of tissue to image. Most protocols require at least 4 to 6 hours of fasting before the procedure. The examination in the MR room takes between 25 and 30 minutes and the entire study, including the preparation at the radiology department takes about 90 minutes.

Evaluation of the small bowel with MR enterography faces one important obstacle: bowel motion that can result in blurring of the images. This is an issue mainly for the contrast-enhanced sequences, considering that the remaining pulse sequences used (single-shot fast spin echo and steady-state free precession) are sufficiently fast. Therefore, most centers administer pharmacologic bowel paralytics to minimize small-bowel motion. Specific techniques vary between institutions; however, 1 mg of glucagon or 20 mg of a dose of hyoscine butylbromide is intravenously administered in a single dose or in split doses after the cine dynamic sequence, to reduce small-bowel peristalsis and related motion artifact.

MR Enterography: Enteral Contrast Agents and Imaging Timing

The ideal protocol for small-bowel distention and filling before MR enterography is still the subject of investigation. Luminal distention is critical for diagnosis of diseases of the small bowel because collapsed bowel may mimic thickened or segmentally hyperenhancing bowel. The most important features concerning enteric contrast agents include uniform and homogeneous filling of the bowel loops, adequate distention of the lumen, high contrast between the lumen and the small bowel, low cost, and absence of serious adverse side effects.

Several enteric contrast agents have been described: plain water, polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution, mannitol, low-concentration barium sulfate, methylcellulose, and gadolinium chelates. These agents are categorized according to their effects on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images: negative (low-signal intensity), positive (high-signal intensity), or biphasic (low-signal intensity on T1-weighted image and high-signal intensity on T2-weighted images).

Biphasic contrast agents are the most commonly used contrast agents for both MR enteroclysis and MR enterography. The low-signal intensity on T1-weighted images observed after its administration improves contrast between the small bowel lumen and the hyperenhancing wall inflammation as well as the demonstration of masses.

On a T2-weighted image, an enhanced contrast between the bright lumen and the dark bowel wall will be observed after biphasic contrast agent administration, improving the detection of endoluminal abnormalities as well as allowing a more effective demonstration of transmural ulcers.

Some studies have demonstrated that low-concentration barium sulfate and PEG solution are better for achieving optimal small bowel filling and distention. PEG solution is a high-osmolality, nonabsorbed contrast medium that has shown to provide excellent intraluminal contrast. Its main side effect is related to the high osmolality that may cause mild diarrhea, which often occurs within 1 hour of ingestion. All patients should be aware of this possibility before undergoing the procedure, so that they may better plan the timing and way to get home after the examination. Moreover, PEG solution is inexpensive. Water is the preferred contrast agent among patients and is associated with the fewest side effects, but it is absorbed along the length of small bowel and currently not commonly used for MR enterography.

The volume and imaging timing of oral contrast administration vary among institutions. In most of them, the volume varies between 1 L and 2 L. In the authors’ institution, we currently ask patients to drink a total of 1 L of PEG solution before the examination (500 mL over 20 minutes, beginning 50 minutes before imaging; then 500 mL more in the next 20 minutes; and, finally, 450 mL of water just before imaging begins). We prefer using plain water immediately before imaging because it is intended only to distend the proximal small bowel and we can, therefore, reduce the amount of hyperosmolar fluid administered and its subsequent side effects. The images should be acquired when the enteric agent reaches the terminal ileum–right colon. Tolan and colleagues advocate imaging 40 minutes after contrast administration and consider that this protocol is effective in terms of both patient compliance and efficient use of time at the MR.

MR Enterography Imaging Protocol

There is no consensus on the optimal imaging protocol used for MR enterography. We apply various pulse sequences in combination and the examinations are always performed at a 1.5-T MR imaging system (Signa HDxT; GE systems, Milwaukee, USA) with an eight-channel phased-array coil.

T2-weighted cholangiopancreatography-like sequence

The examination begins with thick-slab T2-weighted cholangiopancreatography-like sequence, to evaluate if enteric contrast has reached the terminal ileum and/or right colon area. If so, the examination continues ( Fig. 4 ). If not, we consider further administration of 500 mL of enteric contrast agent and then we repeat the sequence 15 to 30 minutes later.

Coronal T2 nondynamic sequences

In our protocol, a coronal 5-mm Half-Fourier Single-Shot T2-weighted sequence (HASTE) is the next step, with and without fat saturation, followed by a 5-mm coronal T2-weigthed sequence steady-state free precession (TrueFISP). Various acronyms are used to describe these gradient-echo sequences, depending on the equipment manufacturer, including TrueFISP, Fast Imaging Employing Steady-state Acquisition (FIESTA), and Balanced Gradient-Echo (GE). Both HASTE and TrueFISP produce high contrast between the lumen and the bowel wall and are particularly effective as a means of obtaining information about extraintestinal abnormalities. TrueFISP sequence eliminates phase shifts caused by motion, thus both fluid and blood appear bright. It is a fast acquisition in which each image is acquired in a few hundred milliseconds. It best depicts mesenteric adenopathy and the prominence of vasa recta in active Crohn disease (the comb sign).

HASTE is considered the best sequence to demonstrate focal wall thickening, fold pattern changes, and ulceration, but it is susceptible to intraluminal motion and often produces intraluminal low-signal-intensity artifacts. Fat-saturated HASTE sequences are added to differentiate submucosal and mesenteric edema from fatty infiltration.

Coronal T2 cine dynamic sequences: evaluation of bowel motility

After these initial coronal fast sequences, dynamic cine true fast imaging with TrueFISP is performed to evaluate the peristalsis. This sequence uses an intermediate-weighted kinematic multiphase sequence (slice thickness 5 mm; FOV 480 × 360 mm; effective matrix 224 × 224; NEX [number of excitations] 1) performing 10 measurements of the same slice over an acquisition time of 9 seconds. It is becoming routinely used in MR enterography protocols and initial data suggest that a simple subjective assessment of motility may add value to conventional anatomic observations.

Diffusion-weighted imaging

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) has been investigated recently in the assessment of bowel inflammation in Crohn disease. In our institution, we acquire a coronal DWI with b-values of 0 and 800 mm 2 /s. It can be also useful in the assessment of small bowel malignancies.

Contrast-enhanced sequences

Coronal high-resolution precontrast T1-weighted LAVA sequence (three-dimensional spoiled gradient echo pulse sequence with fat suppression) is initially acquired. After intravenous contrast agent administration (gadolinium-based agents) at a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg, followed by a 20-mL saline flush (at the rate of 2.0 mL/s), the coronal LAVA sequence is again performed after 30-second and 70-second delays, followed by an entire abdomen axial volumetric sequence at 100-seconds. Coronal LAVA is obtained at the end. These sequences are helpful in the evaluation of neoplastic and inflammatory bowel disorders.

Clinical applications

The main clinical application of MR enterography is the evaluation of patients with suspected or confirmed Crohn disease. In these patients, MR enterography may provide information on disease activity and may demonstrate associated complications.

MR enterography has a less well documented developing clinical application, which consists of the evaluation of other small-bowel diseases, including various benign and malignant neoplasms arising in isolation or along with polyposis syndromes ( Box 1 ).

Evaluation of benign and malignant neoplasms

Polyposis syndromes (eg, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome)

Celiac disease

Inflammatory conditions (vasculitis, treatment-induced enteritis)

Meckel diverticulum

Intussusception

Postoperative adhesions

Crohn Disease: Initial Evaluation and Assessment of Inflammatory Activity

Crohn disease has a worldwide distribution; it is more prevalent in Europe and North America. The peak incidence is in adolescents and young adults between 15 and 25 years of age and a second peak is seen between 50 and 80 years of age. The disease is characterized by bowel inflammation, which can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract with relapses and remissions throughout its course. Although the precise cause of Crohn disease is unknown, there is evidence that the disease is due to an abnormal mucosal response to an unknown antigen. Shanahan suggests that there are genetically susceptible patients.

Crohn disease predominantly involves the terminal ileum and ileocecal region in 90% of the patients with small bowel compromise. In 40% to 55% of these patients, the ileum and the colon are both affected, whereas in a minority of patients (between 15% and 25%) the lesion affects only the colon. Involvement of other parts of the gastrointestinal tract does occur but is rare. Patients may present with vague abdominal symptoms, watery diarrhea, or complications such as perineal sinuses, anorectal fistulas, and abscesses.

Characteristic pathologic findings of Crohn disease in the gastrointestinal tract include transmural granulomatous inflammation with a discontinuous involvement. A pathognomonic feature of this disease is the presence of clearly defined normal segments between diseased segments known as skip lesions. The earliest macroscopic findings in Crohn disease are seen in the mucosa and submucosa and consist of aphthous ulceration, hyperemia, and edema. With increasing severity, transmural involvement is demonstrated, with the shallow ulcers becoming deeper and coalescent, resulting in linear and transversal large ulcerations. The presence of islands of normal mucosa interspersed between deep ulcers leads to the formation of a cobblestone pattern. Later, these extensive transmural ulcerations may be associated with luminal narrowing in the affected segment. This transmural ulceration can evolve to extramural abscesses or fistulas.

The edematous bowel with transmural involvement becomes aperistaltic, causing obstructive symptoms. In long-standing disease, chronic obstruction can develop secondary to scarring and stenosis. Extramural manifestations of Crohn disease are fistulas, abscesses, adhesions, creeping fat, and enlargement of lymph nodes. Extraintestinal manifestations are common and include arthritis; cholelithiasis; ocular manifestations; dermatologic abnormalities; and, in children, growth retardation.

The primary goal of radiology in the evaluation Crohn disease is to provide information that may allow the initial diagnosis of the inflammatory process, predict disease activity, and monitor therapeutic response.

The diagnosis of Crohn disease is based on a combination of clinical, laboratory, histologic, and imaging findings. The imaging characteristics and distribution of the disease give supportive evidence for the diagnosis. Traditionally, the SBFT has been the standard imaging method used to assess patients with Crohn disease. However, some studies have demonstrated that this imaging method does not allow accurate detection of disease activity, mainly because it does not provide direct information with respect to the state of the bowel wall and extraluminal extension of the disease. The accuracy may be limited by overlapping bowel loops. In this setting, the role of cross-sectional imaging has expanded with the recent advances in CT scan and MR imaging that have the main advantage of direct evaluation of the bowel wall and perienteric tissues. This means a complete change in the diagnostic approach: from the analysis of the bowel lumen to the direct evaluation of parietal thickness, as well as the assessment of the perienteric involvement.

Then, with cross-sectional imaging, after confirmation of the diagnosis, it is important to evaluate the number, length, and locations of the segments involved. Later, the second requisite is to evaluate whether there is bowel stenosis and, if so, it needs to be classified in inflammatory or fibrous, because treatment will be different according to this classification. Furthermore, if active inflammation is identified, it is important to discriminate between mild, moderate, and severe inflammation, to establish appropriate medical or surgical treatment. The identification of mesenteric complications must be also reported, including abscesses and fistulas, because they influence the choice of treatment. Many new therapeutic strategies have been developed in the last decade, allowing the gastroenterologist and surgeons to treat almost all different presentations of Crohn disease. The success of these strategies depends on accurate diagnosis of the nature and extent of disease. Thus, it is necessary, from now on, not only to diagnose Crohn disease but also to assess its location, subtype and severity.

CT enterography is an accurate technique to evaluate Crohn disease, providing details about the bowel wall and perienteric tissues, although superficial lesions cannot be accurately visualized. This method can show clearly active Crohn disease and its complications because of its high spatial resolution. Although CT enterography is now widely used in the evaluation of Crohn disease, the exposure of adolescents and young adults to ionizing radiation is an important issue, specially because there is a frequent need for reassessment these patients, due the chronicity of the disease.

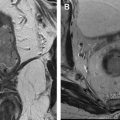

MR enterography is an alternative method for the evaluation of Crohn disease and it clearly demonstrates endoluminal, mural, and extramural enteric changes. In addition, it can provide functional information concerning peristalsis of the involved segment through the dynamic cine sequences and accurately display bowel wall changes in early Crohn disease. Its accuracy in the diagnosis and depiction of Crohn disease extent is similar to CT enterography and superior to SBFT. Lee and colleagues demonstrated that sensitivities for the detection of extraenteric complications of Crohn disease were significantly higher for CT and MR enterography (100% for both) than for SBFT (32%–37%). They also demonstrated a high intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility of these cross-sectional methods. Another pivotal role of the cross-sectional imaging methods is to monitor disease activity and severity.

MR enterography findings in Crohn disease

The main imaging findings on MR enterography are: mural thickening, mural hyperenhancement, parietal stratification, creeping fat, lymphadenomegaly, engorged of the vasa recta (the comb sign), fistulas or abscesses ( Box 2 ).