Soft tissue masses may be encountered in the foot and ankle and may represent true neoplasms, malignant or benign, or other, nonneoplastic entities that mimic musculoskeletal tumors. This article reviews common soft tissue masses encountered in the foot or ankle, highlights their MR imaging appearance, and outlines common pitfalls. Technical considerations for imaging soft tissue masses in the foot and ankle are discussed. On MR imaging, T1-weighted and T2-weighted signal intensity, contrast enhancement characteristics, and lesion location, together with patient demographics, history and physical examination, and findings on radiographs, can be useful in characterizing masses in the foot and ankle.

Key points

- •

Soft tissue masses in the foot and ankle may represent true neoplasms or other, nonneoplastic entities that mimic musculoskeletal tumors. Malignant tumors can occur, but are rare.

- •

Although a definitive diagnosis may not be possible, imaging characteristics can help narrow the diagnosis for a soft tissue mass and, occasionally, provide a specific diagnosis.

- •

On reviewing MR imaging, consider signal intensity, contrast enhancement, lesion location, association with anatomic structures, findings on radiographs, patient history, examination, and demographics.

- •

Some solid masses have high T2 signal intensity and can be mistaken for cysts. Intravenous contrast helps in making the distinction.

- •

Malignant sarcomas can be nonaggressive in appearance and can demonstrate indolent growth.

Soft tissue masses may be encountered in the foot and ankle as incidental findings or as part of the workup of a palpable mass or other abnormality. These lesions may represent true neoplasms, either malignant or benign, or may represent other, nonneoplastic entities that mimic musculoskeletal tumors. The goal of this article is to review common soft tissue masses that can be encountered in the foot or ankle, highlight their MR imaging appearance, and outline common pitfalls. Technical considerations for imaging of soft tissue masses in the foot and ankle are also discussed.

Background

The incidence of different lesions in the foot and ankle is difficult to quantify, because reported series differ in terms of anatomy covered, patient age, and the kinds of masses included. Overall, true soft tissue neoplasms of the foot and ankle are uncommon. However, soft tissue masses encountered in the foot include not only true neoplasms, as classified by the World Health Organization, but also a variety of cystic and solid benign masses—and even some normal anatomic structures—that are relatively common and that can be mistaken for tumors. Kirby and colleagues reviewed a series of 83 consecutive biopsied soft tissue masses in the foot and ankle and found 87% were benign and 13% were malignant. Berquist and Kransdorf presented a compilation of soft tissue masses from a several different studies. In their compilation, the most common benign lesions were ganglion cyst, plantar fibroma, giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath, hemangioma, lipoma, soft tissue chondroma, and benign nerve sheath tumors. The most common malignant lesions were malignant vascular tumors, synovial sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, melanotic clear cell tumor, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.

Background

The incidence of different lesions in the foot and ankle is difficult to quantify, because reported series differ in terms of anatomy covered, patient age, and the kinds of masses included. Overall, true soft tissue neoplasms of the foot and ankle are uncommon. However, soft tissue masses encountered in the foot include not only true neoplasms, as classified by the World Health Organization, but also a variety of cystic and solid benign masses—and even some normal anatomic structures—that are relatively common and that can be mistaken for tumors. Kirby and colleagues reviewed a series of 83 consecutive biopsied soft tissue masses in the foot and ankle and found 87% were benign and 13% were malignant. Berquist and Kransdorf presented a compilation of soft tissue masses from a several different studies. In their compilation, the most common benign lesions were ganglion cyst, plantar fibroma, giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath, hemangioma, lipoma, soft tissue chondroma, and benign nerve sheath tumors. The most common malignant lesions were malignant vascular tumors, synovial sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, melanotic clear cell tumor, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma.

Imaging evaluation of soft tissue masses

MR imaging is the preferred method for evaluation of soft tissue tumors because of the high intrinsic soft tissue contrast, demonstration of features that can aid in tissue characterization, and accuracy for demonstrating extent of bone and soft tissue involvement. Nonetheless, radiographs remain an important adjunct modality for evaluation of soft tissue tumors, in particular because radiographs are superior to MR imaging in demonstrating soft tissue calcifications and reactive changes in bone. Radiographs may also demonstrate large fatty masses or effacement of usual fat planes. Gartner and colleagues found that 62% of radiographs (n = 454) in patients with proven soft tissue tumors had positive radiographic findings.

Ultrasound imaging can differentiate between cystic and solid masses, can help in characterization of some masses such as lipomas, vascular lesions, and nerve sheath tumors, and can be used for image guidance of lesion aspiration and biopsy. In general, ultrasound imaging requires sufficient operator and radiologist expertise to be most useful.

Computed tomography (CT) scans can also be useful in evaluation of soft tissue masses about the foot and ankle, although they lack the level of intrinsic soft tissue contrast inherent in MR images and require ionizing radiation. However, CT images can demonstrate soft tissue calcifications such as phleboliths, lesion matrix mineralization, and reactive changes in bone, and can be useful in evaluation of fatty lesions. Intravenous (IV) contrast-enhanced CT images can help to demonstrate masses that might otherwise not be distinguishable from surrounding soft tissue and CT angiographic techniques can reveal features of vascular malformations and information about lesion vascularity. The use of dual energy CT techniques to demonstrate monosodium urate content for characterization of gouty tophi has also been described.

MR imaging techniques

Effective MR imaging depends on producing images of high spatial resolution. Images should be obtained using a local coil and, whenever possible, a small field of view, targeted to the area of interest. In the workup of soft tissue masses, however, this must be balanced against the need to include the entire extent of the lesion and its surrounding soft tissues. Imaging planes should be optimized to best demonstrate the relationship between the lesion and surrounding anatomic structures.

Imaging protocols vary, but should include T1-weighted (T1W) images and fluid-sensitive sequences. T2-weighted (T2W) images without fat saturation are useful, because classic early descriptions of mass lesions described their T2 signal intensity characteristics and because T2 images without fat saturation are more sensitive for detection of signal heterogeneity within lesions. However, practically speaking, many protocols eschew T2W images in favor of fat-saturated T2-weighted, short tau inversion recovery (STIR), and fat-saturated proton density-weighted images.

Administration of IV contrast allows for distinction between cystic and solid lesions, with cysts demonstrating only a thin rim of peripheral enhancement and no internal enhancement. To assess for the presence of contrast enhancement, it is important to compare sequences that are identical in imaging parameters. Although precontrast and postcontrast images are generally performed using frequency selective fat saturated T1W sequences, it can be difficult to achieve homogeneous fat saturation in the foot and ankle. In those cases, preconstrast and postcontrast imaging on T1W images without fat saturation can serve as an alternative, either by direct comparison, or based on subtraction of the precontrast and postcontrast images. The use of Dixon techniques has also been described as a means to provide more robust fat saturation. Stabilization of the foot within the coil is important to minimize motion and to facilitate the use of subtraction images.

Some supplementary MR imaging sequences can be considered. Production of diagnostic images can be particularly challenging in the setting of hardware or postoperative changes. The use of various metal artifact reduction techniques has been described. T2*-weighted gradient echo sequences can be used to demonstrate blooming owing to the presence of hemosiderin, which can be seen in giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath (GCT-TS) and pigmented villonodular synovitis, and which can also be caused by dense calcification. Hemosiderin can also occasionally be seen surrounding vascular tumors that have leaked or at sites of previous hematoma. The use of diffusion weighted MR images and MR spectroscopy to help characterize musculoskeletal soft tissue masses has been described, but these techniques are not yet in common clinical use in the musculoskeletal system.

Systematic approach to analysis

Although it may not be possible to arrive at a definitive diagnosis for every soft tissue tumor encountered in the foot and ankle, imaging characteristics can help to narrow the differential diagnosis for a soft tissue mass and in some cases can help to arrive at a specific diagnosis. Characteristics such as signal intensity on T1W images, signal intensity on T2W images, contrast enhancement characteristics, lesion location, and association with other anatomic structures, as well as findings on correlative radiographs, can be useful in this regard ( Box 1 ).

T1-weighted signal

T2-weighted signal

Contrast enhancement

- •

Peripheral/central

- ○

Peripheral: thin/smooth versus thick/irregular

- ○

- •

Homogeneous/heterogeneous

- •

Dynamic enhancement: early or late

- •

Special imaging features

- •

Tail sign

- •

Target sign

- •

Characteristic location

- •

Bursae

- •

Associated anatomy

- •

Tendon

- •

Nerve

- •

Vessel

- •

Plantar fascia

- •

Joint

- •

Many mass lesions are isointense to muscle on T1W images and relatively hyperintense on T2W images. However, substances that seem to be high signal on T1W images include fat, proteinaceous fluid (of specific concentration range), hemorrhage (methemoglobin phase), melanin, and, of course, gadolinium ( Box 2 ). Substances that seem to be low signal on T2W images include calcification, fibrous material (scar tissue, fibrous neoplasm), and hemosiderin ( Box 3 ). IV contrast can help to distinguish cystic lesions, which demonstrate peripheral rim enhancement, from solid lesions, which have high T2 signal intensity on fluid-sensitive images, but demonstrate internal enhancement. Dynamic contrast enhancement can be used to assess the degree of lesion vascularity. Various forms of “tail signs” can be seen in nerve sheath tumors, ganglia, and, after contrast administration, in plantar fibromas, whereas a “target sign” is highly suggestive of a nerve sheath tumors. Bursae occur in characteristic anatomic locations, whereas other lesions characteristically arise in association with other anatomic structures, for example, giant cells tumors of tendon sheath (tendons), nerve sheath tumors (nerves), plantar fibromas (plantar fascia), and synovial cysts (joints). In addition, radiographs may provide findings that can aid in diagnosis, such as phleboliths (hemangiomas), foreign bodies (foreign body granulomas), pleomorphic calcifications (synovial sarcomas), calcified masses (gout), and well-defined erosions (gout, giant cell tumor of tendon sheath).

- •

Fat

- •

Proteinaceous fluid

- •

Methemoglobin

- •

Melanin

- •

Gadolinium

- •

Calcification

- •

Fibrous tissue—scar

- •

Fibrous tissue—fibrous neoplasms

- •

Hemosiderin

With this in mind, a systematic approach can be applied to aid in decision making when a mass is encountered in the foot or ankle ( Boxes 4–6 ).

- 1.

Does the lesion suppress using chemically specific (frequency-selective) fat saturation? If so, it is composed of fat and the differential would include entities such as lipoma, well-differentiated liposarcoma (rare in the foot or ankle), or hemangioma.

- 2.

Does the radiograph show a focal collection of phleboliths, suggesting an hemangioma?

- 3.

Does the enhancement pattern indicate a cystic structure, such as a hemorrhagic or proteinaceous ganglion cyst?

- 1.

Does the radiograph show rounded or ovoid calcified mass, as might be seen in a gouty tophus?

- 2.

Is there blooming on T2*-weighted images? If there are no calcifications on the radiographic to account for this, then giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath or residua from hemorrhage around a vascular lesion or old hematoma should be considered.

- 3.

Does the lesion location suggest a diagnosis, such as a giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath arising from a tendon sheath or a plantar fibroma arising from the plantar fascia?

- 1.

If there is a thin rim of peripheral enhancement, this suggests a cystic structure, such as a ganglion cyst. Be aware that soft tissue chondromas can also demonstrate thin peripheral enhancement. It also important to confirm that the cystic structure is not a smaller component of a larger mixed cystic and solid structure.

- 2.

If the peripheral enhancement is thick, rather than thin, this could indicate and inflamed or infected cyst or bursa or an abscess or, alternatively, a solid lesion with central necrosis. Nerve sheath tumors that display a “target sign” on T2-weighted images may also show predominantly peripheral enhancement on postcontrast images.

- 3.

Is there central enhancement? If so, a solid high T2 signal mass should be considered. This can be seen with a variety of benign and malignant lesions and the differential includes a synovial or other myxoid sarcomas, other myxomatous soft tissue masses, and hemangiomas.

Benign soft tissue tumors

Plantar Fibroma

Plantar fibromas are the most common solid soft tissue neoplasm encountered in the foot and ankle in Berquist and Kransdorf’s compilation, and the second most common mass after ganglion cysts. A plantar fibroma is a nodular mass composed of spindle cells and variable amounts of collagen that arises in the plantar aponeurosis of the foot. Plantar fibromas are related to palmar fibromas seen in Dupuytren disease, as well as other forms of fibromatosis. They typically occur in patients older than 30 years of age, and more commonly in men. The etiology is uncertain, but likely multifactorial, with family history and trauma both implicated.

Patients with plantar fibromas may present with a palpable nodule or area of focal thickening along the plantar aspect of the foot and may experience mild pain after standing or walking for long periods. Lesions may be bilateral in 20% to 50% of patients.

On MR imaging, plantar fibromas are seen as nodular masses adherent to the plantar aponeurosis, typically medial rather than lateral. They are well-defined with respect to the overlying plantar subcutaneous fat, but are often not well-demarcated with respect to the plantar aponeurosis and underlying muscle. Most lesions are heterogeneous in signal intensity, isointense to slightly hyperintense to muscle on fluid-sensitive sequences, and demonstrate heterogeneous, enhancement, which is variable in degree. Contrast enhancement may extend along the plantar aponeurosis, creating a “fascial tail” sign. Multiple lesions can be present at the same time (synchronous) and new lesions can arise after treatment (metachronous). Lesions do not metastasize, but can recur locally ( Fig. 1 ).

Giant Cell Tumor of the Tendon Sheath

A GCT-TS is a benign neoplastic mass consisting of mononuclear and inflammatory cells, arising from the tendon sheath. The lesion can be localized or diffuse. Histologically, GCT-TS resembles intraarticular pigmented villonodular synovitis. GCT-TS occurs most commonly in the hands and feet, with about 17% occurring in the foot and ankle. In data compiled by Berquist and Kransdorf, GCT-TS was the third most common benign mass encountered in the foot and ankle. Patients with GCT-TS present with a usually painless mass that develops gradually, often over several years. GCT-TS usually occurs in patients between 30 to 50 years of age and is more common in women (F:M 2:1).

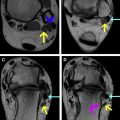

Lesions are typically occult on radiographs, but, on occasion, a focal soft tissue mass and/or nonaggressive erosion of the abutting bone may be visible. The MR imaging appearance of GCT-TS can be highly suggestive of the diagnosis. On MR imaging, the lesions appear as focal masses that are adherent to the surface of a tendon. Small lesions may be rounded, but large, lobulated lesions can also be seen. The lesions are classically low signal on both T1- and T2-weighted images. Low T2 signal is attributed to abundant collagen and hemosiderin. When sufficient hemosiderin is present, these lesions may demonstrate blooming on T2* gradient echo images, that is, the lesion may demonstrate low signal that appears darker and/or more extensive on the T2*W gradient echo images. However, some lesions may not contain enough hemosiderin to be T1 and T2 hypointense or to cause blooming artifact on gradient echo images. The gadolinium enhancement pattern is variable, but lesions often show pronounced homogeneous enhancement ( Fig. 2 ).

A fibroma of the tendon sheath can a similar MR appearance, but fibromas are less common in this location and are not characterized by hemosiderin or by blooming on T2*W gradient echo images.

Hemangioma

Hemangiomas are benign vascular lesions that consist of hyperplastic endothelial cells, together with mast cells, and may be superficial (cutaneous or subcutaneous) or deep. These lesions are often associated with fat (angiolipoma), fibrous tissue, and/or smooth muscle. Based on the vessels that comprise them, hemangiomas can be further classified histologically as capillary, cavernous, venous, or arteriovenous.

Hemangiomas are common, accounting for 7% of all benign soft tissue lesions and 9% of benign lesions in the foot and ankle. Hemangiomas are common in infancy and childhood, but can occur at any age. Most patients present by 30 years of age. The incidence is similar in men and women. Patients may present with blue discoloration on the skin. Hemangiomas may fluctuate in size and can become painful after exercise, owing to shunting of blood away from the surrounding tissue.

Radiographs play an important role in the imaging diagnosis of hemangioma, because they demonstrate phleboliths (focal dystrophic mineralization within thrombus) in up to 50% of cavernous hemangiomas ( Fig. 3 C ). In up to 33% of patients, radiographs may demonstrate a soft tissue mass and bony reactive changes, such as cortical or periosteal thickening.

On MR imaging, hemangiomas may be either well- or poorly circumscribed. Lesions may have high T1 signal owing to varying amounts of fatty overgrowth or hemorrhage. They are typically high signal on T2W images, owing to the presence of slow flow, and fluid–fluid levels may be visible. When high flow vessels are present, serpiginous signal voids (“flow voids”) will be seen on nonflow sensitive sequences. Rounded foci of low signal within the lesions can indicate the presence of phleboliths and should be correlated with radiographs. Intramuscular lesions may be accompanied by a small amount of surrounding fatty atrophy owing to vascular steal phenomenon. If perilesional hemorrhage has occurred, then low T2 signal hemosiderin may be seen at the periphery of the lesion and can cause blooming on T2*-weighted gradient echo images. Hemangiomas typically show prominent contrast enhancement, although delayed enhancement can also occur. As on radiographs, reactive changes may be visible in adjoining segments of bone ( Fig. 3 A, B).

Because a focal hemangioma with slow flow can appear as a focal high T2 mass, care should be taken not to mistake an hemangioma for a cyst or for a myxoid soft tissue mass. IV contrast and ultrasound can be helpful in this regard.

Lipoma

Lipomas are benign soft tissue tumors composed of mature white adipocytes, histologically identical to adipose fat. Overall, lipomas are the most common soft tissue tumor in adults, with an incidence of up to 2.1 per 100 individuals. In Berquist and Kransdorf’s compilation, lipomas were the fifth most common soft tissue mass in the foot and ankle.

A simple lipoma is composed entirely of fat. It may contain several thin septations, but thickened septations (>2 mm) and nodular soft tissue areas within the fatty tumor should raise concern for malignancy. Other features concerning for malignancy include patient age, large lesion size (>10 cm), thickened septae, globular areas of nonfatty signal intensity, and lesions with less than 75% fat content. It should be noted, however, that a substantial percentage of benign lipomas, as well as lipoma variants, contain nonfatty components.

On radiographs, lipomas are often occult. When visible, they appear as a radiolucent mass, occasionally with thin septations or calcifications. On MR imaging, lipomas follow the signal of subcutaneous or intramedullary fat on all sequences. A simple lipoma is homogeneously high signal on T1W images and that high signal should suppress on T1W images obtained with chemically-specific (“frequency selective”) fat saturation. As noted, although a lipoma may have thin septations, thickened septations (>2 mm) or nodular soft tissue components raise concern for malignancy. The lesion may have a thin surrounding capsule, although may be variably unencapsulated. Lipomas may occur in subcutaneous fat, deep fat, or between or within muscles. When lipomas occur within muscle, longitudinal muscle fibers may traverse the lipoma and should not be mistaken for thickened septae ( Fig. 4 ).

Liposarcomas in the foot and ankle are rare. Well-differentiated liposarcomas contain large amounts of normal appearing fat and should be distinguished from lipoma using the criteria listed above.

Soft Tissue Chondroma

Soft tissue chondromas are benign extraosseous and extrasynovial soft tissue tumors composed predominantly of mature hyaline cartilage. Soft tissue chondromas occur over a broad age range (mean, 34.5 years) and demonstrate a slight male predominance (3:2). The majority of soft tissue chondromas arise on the fingers and hands, followed by toes and feet.

Most soft tissue chondromas are solitary and occur as a soft tissue mass near tendons and joints. On imaging, soft tissue chondromas are lobulated and well-demarcated, with central and peripheral calcifications that are arclike, punctate, spiculated, or coarsely geometric. On MR imaging, soft tissue chondromas demonstrate the high T2 signal typical of chondroid lesions, but may have small signal voids owing to the matrix calcifications. Large chondromas may be difficult to distinguish from chondrosarcoma ( Fig. 5 ).

Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors (PNSTs) include benign and malignant PNSTs and are classified as nerve sheath tumors by the World Health Organization. Benign PNSTs include both neurofibromas and the more common schwannomas (also known as neurilemmomas). Overall, these account for approximately 10.5% of benign soft tissue tumors. In the Berquist and Kransdorf compilation, benign nerve sheath tumors represented the seventh most common benign soft tissue mass in the foot and ankle. Schwannomas are composed of differentiated neoplastic Schwann cells, whereas neurofibromas consist of a mix of differentiated Schwann cells together with myelinated and unmyelinated axons in an extracellular matrix. Both neurofibromas and schwannomas are typically seen in patients 20 to 40 years of age. Clinically, patients may present with motor or sensory disturbances or both. Patients with neurofibromatosis may have multiple lesions. In the foot, most neurofibromas occur in the heel and great toe. Neurofibromas are typically seen along cutaneous nerves. Schwannomas typically occur along the flexor surface of the extremity.

Although neurofibromas arise directly from the nerve and schwannomas arise from Schwann cells and lie eccentric to the nerve, the 2 lesions can be difficult to distinguish at imaging. In both cases, the lesion typically appears as a well-defined, smooth-bordered, fusiform mass aligned along the nerve. Signal intensity is often nonspecific, isointense to muscle on T1W and slightly hyperintense to fat on T2W images. In some cases, the lesions may have a “target sign” appearance on T2W images, with higher signal peripherally and lower signal centrally, corresponding to myxoid and fibrocollagenous content, respectively. The target appearance is seen in both neurofibromas and schwannomas, though more commonly in neurofibromas. Contrast enhancement is variable. On occasion, the nerve from which the tumor arises becomes thickened immediately adjacent to the tumor, giving rise to a “tail sign.” When the PNST enlarges, a surrounding rim of fat is maintained—this becomes especially apparent on lesions that arise within muscle and is termed the “split fat sign” ( Fig. 6 ).