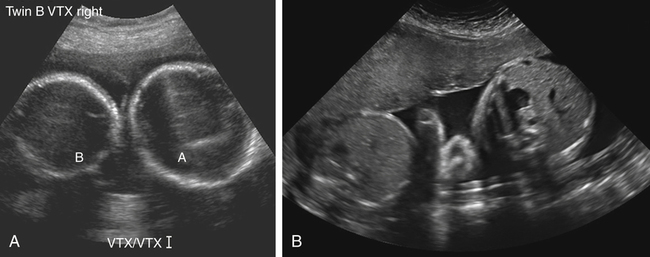

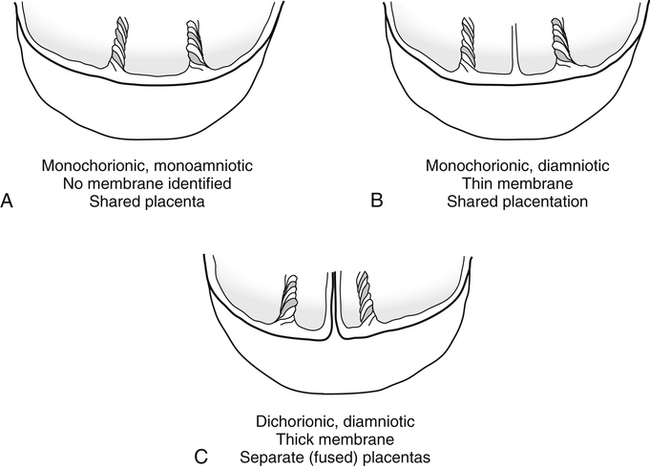

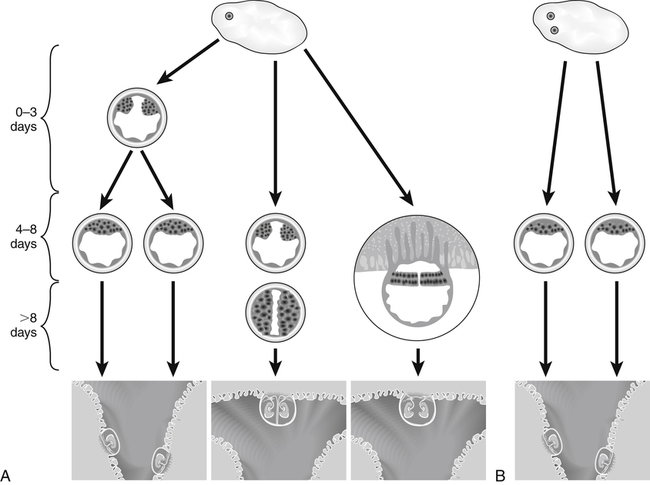

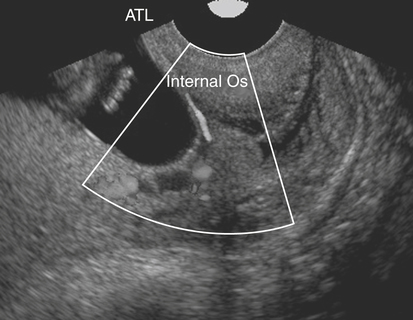

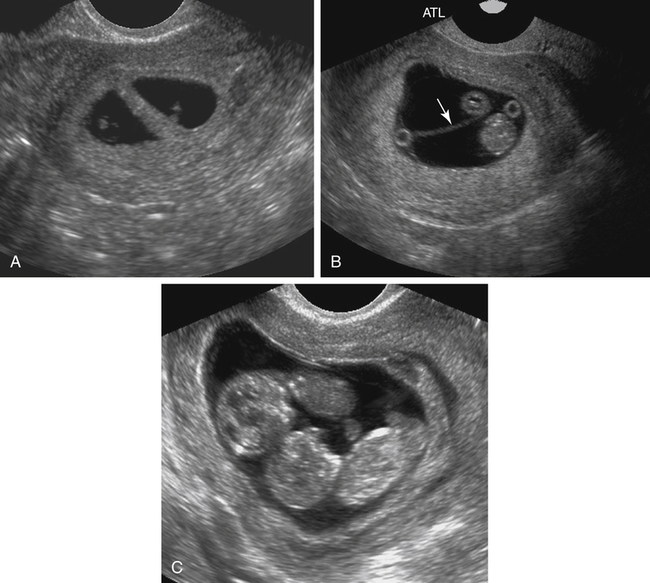

Diane J. Youngs and Allan E. Neis • Discuss the role of sonography in evaluation of a multiple gestation. • Discuss the embryology and incidence of multiple gestations. • Describe the sonographic criteria used in evaluation of zygosity, chorionicity, and amnionicity in a multiple gestation. • List maternal and fetal complications associated with multiple gestations. • Describe the abnormalities unique to monochorionic multiple gestations. The incidence rate of twin and higher order multiple gestations has increased steadily through the years, with twin births occurring in the United States at a rate of approximately 32.2 per 1000 births in 2007 compared with 24.8 per 1000 births in 1995.1 This increase is thought to be the result of the widespread use of assisted reproductive technology (e.g., ovulation induction, in vitro fertilization) and an aging maternal population. The number of higher order multiple births increased 400% from 1980-1998, but the numbers have demonstrated a downward trend since 1998. The more recent decline of higher order multiple gestations has been primarily attributed to the American Society of Reproductive Medicine publishing guidelines that recommend limiting the number of embryos transferred during assisted reproductive technology.1 Identification of multiple gestations is important because of the significantly increased risk for both the mother and the fetus. In the United States in 2007, 3% of twins and 7% of triplets died during infancy compared with less than 1% of all singletons.1 Early identification of multiple gestations allows careful screening for complications. The number of chorions and amnions that develop in a multiple gestation is referred to as chorionicity and amnionicity; another term for chorionicity is placentation (Fig. 22-2). Two chorions (dichorionic) produce two placentation sites, which presents the least risky form of twinning. Dichorionic twinning accounts for 80% of all natural twinning.2 The development of one chorion (monochorionic) results in a shared placental site, which places the pregnancy at higher risk. Although monochorionic twinning is less common, this type of placentation accounts for 50% of twin mortalities.2 The development of a single amnion is termed monoamniotic, and the presence of two amnions is referred to as diamniotic. Monoamniotic twin gestations have the highest incidence of mortality because sharing the amniotic space increases the risk for cord accidents. Monozygotic, or identical, twins result when one ovum is fertilized by a single sperm, and the gestation subsequently splits to form two embryos. The splitting of the embryos is called cleavage. The incidence of monozygotic twins remains steady at 1 in 250 births,3 representing the least common form of twinning and the most risky. Monozygotic twinning can result in a shared placental site, which can lead to serious complications discussed later in this chapter. The chorionicity and amnionicity in monozygotic twinning varies and depends on the number of days at which cleavage occurred (Fig. 22-3). If the zygote splits between 0 and 3 days, the gestation is dichorionic, diamniotic. However, most monozygotic twins split between 4 and 8 days resulting in a monochorionic, diamniotic gestation. The later the cleavage, the more that is shared. Cleavage after day 8 results in a pregnancy that is monochorionic and monoamniotic, which places the pregnancy at an even higher risk for complications. Very rarely, cleavage may occur 13 days after conception, resulting in conjoined twins. Conjoined twins are physically fused and often share internal organs. Prematurity and low birth weight are major contributing factors to the increased morbidity and mortality found in multiple gestations. Premature labor is the most common complication associated with multiple gestations and is thought to occur because of increased uterine volume. Twin pregnancies are five times more likely than singleton pregnancies to be complicated by premature labor, and the risk for triplet gestations is 10 times higher.2 The role of sonography in these patients includes evaluation of the cervical length for thinning and for evidence of funneling. Transvaginal rather than transabdominal sonography should be considered for monitoring cervical length because it is the most reproducible technique for cervical assessment. As in a singleton pregnancy, either a cervical length of less than 2.5 cm or the presence of funneling at the internal cervical os is considered a significant finding associated with premature delivery (Fig. 22-4). The birth weight of twins statistically averages 10% less than the birth weight of singletons of comparable gestational age. In 2007, 57% of twins and 96% of triplets born in the United States had low birth weight.1 Because 14% to 25% of twins are considered to have growth restriction,3 evaluation of fetal measurements and growth for any discordance is important. A fetal weight less than the 10th percentile is suggestive of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), especially in the setting of oligohydramnios and high resistance as demonstrated on the umbilical artery pulsed Doppler waveform. In a multiple gestation, IUGR can be caused by the same conditions as in a singleton pregnancy (e.g., placental insufficiency, fetal anomalies). In addition, IUGR may be the result of an abnormality unique to multiple gestations, such as twin-twin transfusion syndrome. If IUGR is suspected, serial sonography with pulsed Doppler evaluation of the umbilical cord and biophysical profile is generally indicated. The incidence of a major fetal anomaly in a multiple gestation is 4% compared with 2% in a singleton pregnancy, including a 4.6% chance of having Down syndrome.3 First-trimester and second-trimester screening for assessing risk of a fetus with Down syndrome in a twin gestation uses maternal age, serum screening, and sonographic evaluation. Because there is an increased risk for major malformations in multiple gestations, it is critical that all fetuses are sonographically evaluated for structural abnormalities. Anomalies affecting the central nervous system are the most common in multiple gestations, especially monozygotic twins.4 Twins and especially triplets are at increased risk for cerebral palsy. Women with multiple gestations are at higher risk for bleeding complications from preterm labor and placental and cord abnormalities such as placental abruption, placenta previa, and vasa previa (Fig. 22-5; see Color Plate 25). Other maternal disorders observed more often in women with multiple gestations include iron deficiency anemia, hyperemesis gravidarum, and thromboembolism.5 One of the most important features of the sonographic evaluation of a multiple gestation is establishing chorionicity and amnionicity. This evaluation is best accomplished by counting the number of fetuses, placentas, yolk sacs, chorionic sacs, and amniotic sacs. The presence of a single yolk sac suggests a monoamniotic gestation. Determining the number of chorionic and amniotic sacs is easiest during the first trimester because the space between separate implantation sites of a dichorionic pregnancy is evident, and the amnion can be identified separate from the chorion (Fig. 22-6).

Multiple Gestation

Embryology of Twinning

Chorionicity and Amnionicity

Zygosity

Complications

Premature Labor

Intrauterine Growth Restriction

Congenital Anomalies

Maternal Complications

Sonographic Evaluation

Chorionicity and Amnionicity

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine