FIGURE 6-12. CTV1, CTV2, and CTV3 delineation in a patient with clinically T2N3aM0 left nasopharyngeal carcinoma who received definitive IMRT.

1. ANATOMY

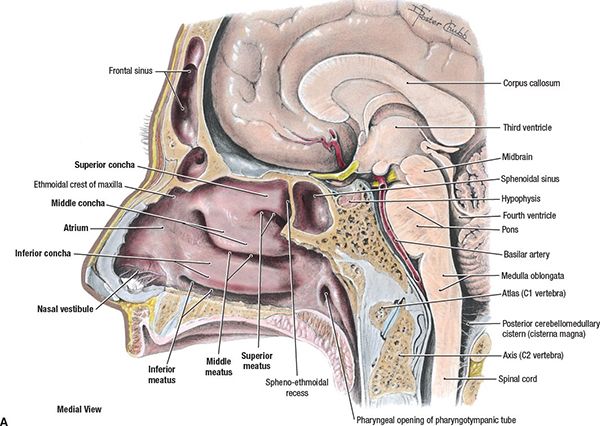

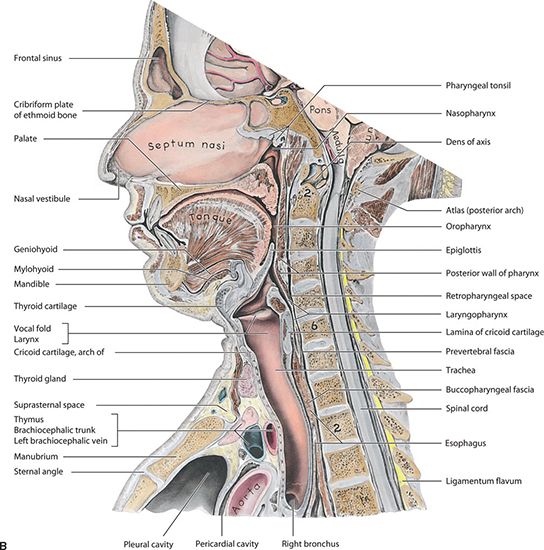

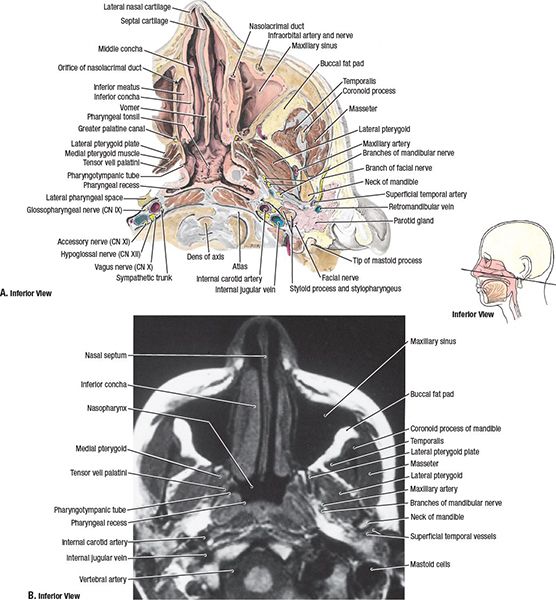

• The nasopharynx is roughly cuboidal; its borders are the posterior choanae anteriorly, the body of the sphenoid superiorly, the clivus and first two cervical vertebrae posteriorly, and the soft palate inferiorly (Fig. 6-1).

• The lateral and posterior walls are composed of the pharyngeal fascia, which extends outward bilaterally along the undersurface of the apex of the petrous pyramid just medial to the carotid canal. The roof of the nasopharynx slopes downward and is continuous with the posterior wall.

• The eustachian tube opens into the lateral wall; the posterior portion of the eustachian tube is cartilaginous and protrudes into the nasopharynx, making a ridge just posterior to the torus tubarius. Just posterior to the torus is a recess called Rosenmüller fossa.

• The roof and the posterior wall of the nasopharynx consist of the clivus and basisphenoid, which are the foundation of the central skull base and cavernous sinus; the bony portion of the eustachian tube lies lateral to the carotid canal.

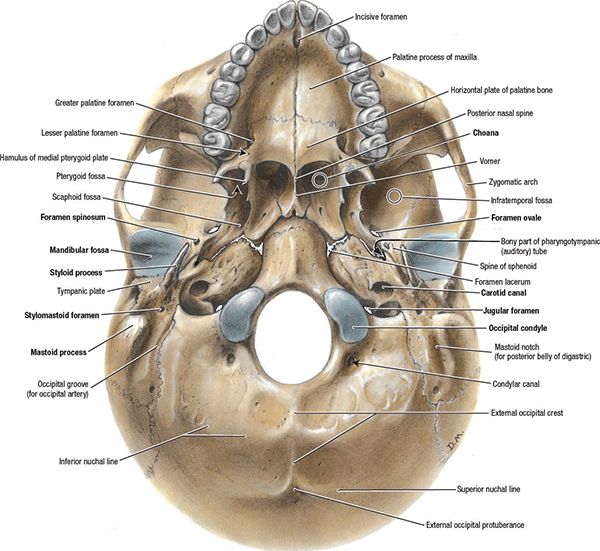

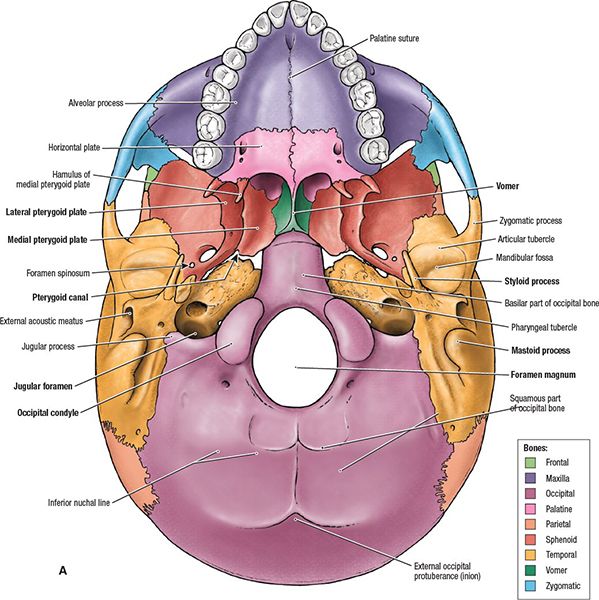

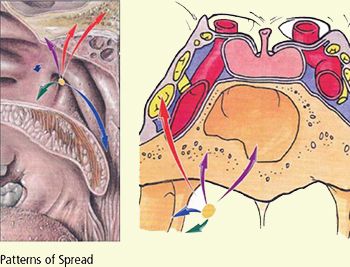

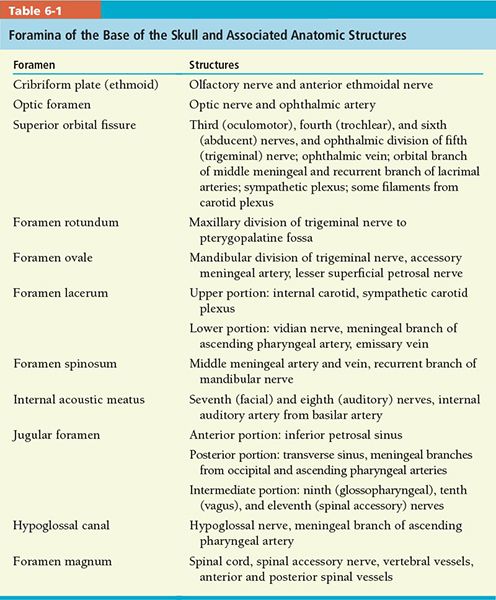

• Many foramina and fissures are located in the base of the skull, through which several structures pass (Table 6-1). Some are potential routes of spread of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Fig. 6-2).

• The jugular fossa, which lies just posterior to the carotid foramen, is usually larger on the right side. The jugular spur separates the pars nervosa from the pars venosum of the fossa.

• Cranial nerve IX lies within the pars nervosa of the jugular fossa, whereas cranial nerves X through XII lie within the pars venosum along with the jugular vein.

• The base of the pterygoid plates is part of the basisphenoid; the pterygopalatine fossa lies between the pterygoid processes and the maxillary sinus and is contiguous with the inferior orbital fissure superiorly and the infratemporal fossa laterally. The foramen rotundum can be seen just above the base of the pterygoid processes.

• The upper pharyngeal musculature attaches to the basisphenoid and styloid process. Levator and tensor veli palatini muscle attachments are visualized along the inferior petrous apex and basisphenoid, respectively.

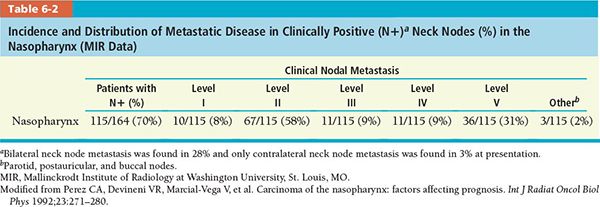

• An extensive submucosal capillary lymphatic plexus exists in the nasopharyngeal region. This can explain the high incidence of neck node metastasis at initial presentation of patients. The tumor initially spreads to the retropharyngeal, junctional, and jugulodigastric lymph nodes, and then along the internal jugular and spinal accessory chains. Incidence and distribution of clinically positive neck nodes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma are shown in Table 6-2.1

FIGURE 6-1. (A) Nasopharynx and related structures in the midsagittal section of the head. (From Agur AMR, Dailey AF. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009:694, with permission.)

FIGURE 6-1. (B) Medial section of the head and neck. (From Moore KL, Dalley AF. Clinical Oriented Anatomy, 4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.)

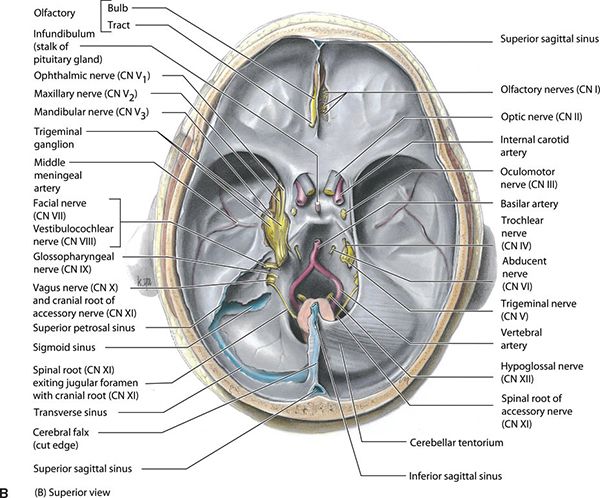

• Lymphatics of the nasopharyngeal mucosa run in an anteroposterior direction to meet in the midline; from there, they drain into a small group of nodes lying near the base of the skull in the space lateral and posterior to the parapharyngeal or retropharyngeal space. This group lies close to cranial nerves IX, X, XI, and XII, which run through the parapharyngeal space (Fig. 6-2B,C).

• Figure 6-3 shows a drawing of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx and also an axial MRI of the same structures.

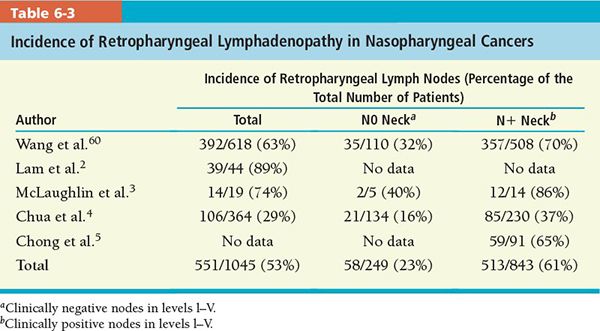

• The retropharyngeal lymph nodes are an important route of spread. The lateral retropharyngeal lymph nodes are located in the retropharyngeal space near the lateral border of the posterior pharyngeal wall and medial to the carotid artery. Directly behind them (Rouviere nodes) are the lateral masses of the atlas (C1). Usually one node occurs on each side, but occasionally two and very rarely three are found, and they can be found even at the level of the hyoid bone (C3). These nodes atrophy with age and may be absent unilaterally, but are rarely absent entirely. Incidence of retropharyngeal lymphadenopathy in nasopharyngeal cancers is shown in Table 6-3.

• Clinically, lymph nodes of the parotid area may also be involved. This route of spread is possible from the lymphatics of the eustachian tube, which may drain by way of the lymph vessels of the tympanic membrane and external auditory canal to the periparotid lymph nodes.

• Another lymphatic pathway from the nasopharynx leads to the deep posterior cervical node at the confluence of the spinal accessory and jugular lymph node chains.6

• A third pathway is to the jugulodigastric node, which is frequently involved in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, according to Lederman.7

2. NATURAL HISTORY

• Carcinoma of the nasopharynx frequently arises from the lateral wall, with a predilection for the fossa of Rosenmüller and the roof of the nasopharynx.

• Tumor may involve the mucosa or grow predominantly in the submucosa, invading adjacent tissues including the nasal cavity. In approximately 5% of patients, tumor may extend into the posterior or medial walls of the maxillary antrum and ethmoids.

• In more advanced stages, tumor may involve the oropharynx, particularly the lateral or posterior wall.

• Superior extension of tumor through the foramen lacerum may result in cranial nerve involvement and destruction of the middle fossa (Figs. 6-2 and 6-4).

• Figure 6-5 graphically illustrates typical patterns of spread in nasopharyngeal cancer.

• The floor of the sphenoid may occasionally be involved.

• Approximately 90% of patients develop lymphadenopathy, which is present in approximately 70% at initial diagnosis.8

• The American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) 2010 staging has some notable changes including the removal of prior T2a disease which is now T1, and therefore stage IIA is now part of stage I. Furthermore, unilateral or bilateral retropharyngeal nodes are classified as N1.

• The incidence of distant metastasis is not related to the stage of the primary tumor, but correlates strongly with the degree of cervical lymph node involvement. In 63 patients with N0 neck, 11 (17%) developed metastatic disease, in contrast to 69 of 93 (74%) with N3 cervical lymphadenopathy.9 The most common site of distant metastasis is bone, followed by lung and liver.10

FIGURE 6-2. (A) Cranium, inferior views. (From Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009:616.)

FIGURE 6-2. Cranium, inferior view. Ibid., 617.

FIGURE 6-2. (B) Superior view of the interior of the base of the skull showing the cranial nerves, dura mater, and blood vessels. On the left side, the dura is cut away to expose the trigeminal cave (cavity) housing the trigeminal ganglion and its roots and the nerves arising from it: CN V1, CN V2, and CN V3. The cerebellar tentorium (L. tentorium cerebelli) is also removed on the left side to show the nerves exiting the internal acoustic meatus (CN VII and CN VIII) and jugular foramen (CN IX, CN X, and CN XI), as well as the transverse and superior petrosal dural venous sinuses. (From Moore KL, Dalley AF II. Clinical Oriented Anatomy, 4th ed. Baltimore, MA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.)

3. DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING SYSTEM

3.1. Signs and Symptoms

• Tumor growth into the posterior nasal fossa can produce nasal obstruction, discharge, or epistaxis. In some cases, the voice may develop a nasal twang.

• The orifice of the eustachian tube can be obstructed by a relatively small tumor; ear pain or a unilateral decrease in hearing can occur. Sometimes blockage of the eustachian tube may produce a middle ear transudate.

• Headache or pain in the temporal or occipital region can occur. Proptosis sometimes results from direct extension of tumor into the orbit.

• Sore throat can occur when tumor involves the oropharynx.

• Although a neck mass elicits medical attention in only 18% to 66% of cases, clinical involvement of cervical lymph nodes on examination at presentation ranges from 60% to 87%.7,11

• Some patients present with cranial nerve involvement. In 218 patients, 26% had cranial nerve involvement, but it was present at initial diagnosis in only 3% of patients.7 Leung et al. reported a 12% incidence of cranial nerve involvement in 564 patients with primary nasopharyngeal carcinoma; it was higher in patients staged with computed tomography (CT) (52 of 177, 29%).12

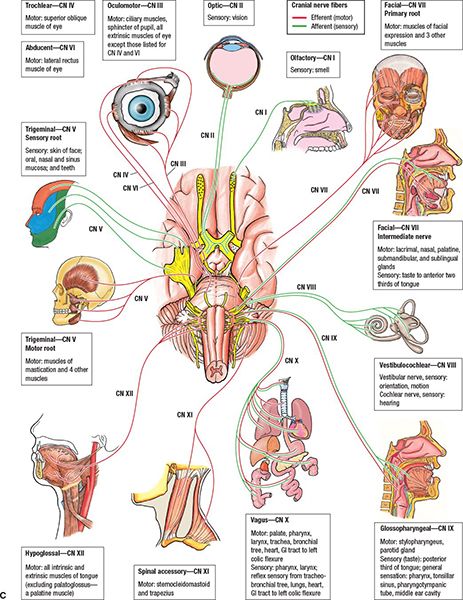

FIGURE 6-2. (C) Illustration of cranial nerves and the functions they control. (From Rubin P, Hansen JT. TNM Staging Atlas with Oncoanatomy, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012:15.)

• Cranial nerves III through VI are involved by extension of tumor up through the foramen lacerum to the cavernous sinus. Cranial nerves VII, VIII, and I are rarely involved (Figs. 6-2C and 6-4).

3.2. Physical Examination

• The flexible fiberoptic nasopharyngolarnygoscope is the main tool to completely examine the upper aerodigestive tract including the nasopharynx. Early lesions mostly occur on the lateral walls or roof of the nasopharynx.

• In early cases, only slight fullness in the Rosenmüller fossa or a submucosal bulge or asymmetry in the roof may be the only evidence of disease. Lymphomas and minor salivary gland tumors have a tendency to remain submucosal until gross progression.

• The site of origin is rarely the nasopharyngeal surface of the soft palate, nor is it often invaded secondarily, even by advanced tumors.

• Nasoscopes may aid us by showing tumor growth into the anterior and superior portions of the nasal cavity. Tumor may be seen submucosally infiltrating along the posterior tonsillar pillars and occasionally down the posterior pharyngeal wall.

• Palpation of neck nodes and measuring the size and lowest extent of lymphadenopathy are important.

• Evaluation of the cranial nerves is essential. The fifth and sixth cranial nerves are most commonly involved. Otitis media and decreased hearing can be found on ear examination. Table 6-4 summarizes functions of the cranial nerves, which should be examined during the initial consultation.

3.3. Imaging

• Imaging evaluation is necessary for staging and treatment planning in all nasopharyngeal carcinomas as well as in posttreatment evaluation.

• The main imaging tools of the nasopharyngeal region are CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET).

• CT scan thickness should be 3 mm or less for treatment planning. The normal anatomy of the nasopharynx as seen on CT is shown in Figure 6-6.

• Unless medically contraindicated, MRI is the preferred primary examination for disease in the nasopharynx, which provides higher sensitivity for deep tumor infiltration (Figs. 6-7 and 6-8).13

• The neck is always included when imaging is performed. Coronal and sagittal sections should be evaluated for all imaging modalities.

• The torus tubarius, eustachian tube orifice, and fossa of Rosenmüller are often asymmetric in appearance. Lymphoid tissue has a tendency to atrophy with age, which can be responsible for superficial contour variation of the nasopharyngeal region. Lymphoid tissue is better visualized with MRI.

• The carotid artery and jugular veins should always be clearly visible in the poststyloid parapharyngeal space, along with at least some surrounding fatty tissue. The intervening cranial nerves IX through XII and the sympathetic chain can sometimes be seen in high-resolution MRI.

• The retropharyngeal lymph nodes are visible on MRI medial to the carotid artery at the border between the poststyloid parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal spaces (Fig. 6-9A,B). The nodes are normally 3 to 5 mm in size in adults and 10 to 15 mm in infants and children.

• The fifth nerve ganglion, within Meckel’s cave, and its branches both inside and outside the cavernous sinus are easily recognized on good-quality MRI and CT.

• The third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves, along with the first division of the trigeminal nerve, are best visualized on coronal MRI as they go through the wall of the cavernous sinus.

• The fat within nasopharyngeal spaces is normally symmetric, although the size of vessels coursing through the spaces may vary slightly; obliteration of fat in MRI or CT is a sign of pathologic involvement.

FIGURE 6-3. Transverse section and MR imaging of nasal cavity and nasopharynx (A) Transverse section of the left side of the head (B) Transverse (axial) MRI scan. (From Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009:720.)

• The third division of the trigeminal nerve exiting the foramen ovale is often seen on MRI.

• Perineural enhancement within the cranial nerve exit and the foramina and prominent enhancement of venous plexuses just below the skull base are normal variants.

3.4. Staging

• There have been some changes in the latest AJCC 2010 staging system from the previous AJCC 2002 staging system. Previous T2a lesions are now designated as T1; therefore stage IIA will now be stage I. Lesions previously staged as T2b are now T2 and therefore stage IIB is now designated as stage II.

• Retropharyngeal lymph nodes are considered N1, regardless of unilateral or bilateral location. The prognostic value was similar to that of unilateral cervical involvement.14

4. PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

• Epidemiological factors: Race, age, and gender have prognostic significance.5 Perez et al. found that patients younger than 50 years had better survival and local control.1 Sham and Choy found similar results in their retrospective analysis of 759 patients.15

• Stage:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree